Heart of Darkness: Rhetoric of Restraint Analysis

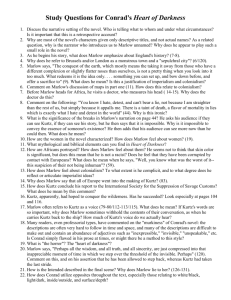

advertisement

The Rhetoric of Restraint in Heart of Darkness Author(s): John A. McClure Source: Nineteenth-Century Fiction, Vol. 32, No. 3 (Dec., 1977), pp. 310-326 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2933387 . Accessed: 11/05/2011 15:29 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucal. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Nineteenth-Century Fiction. http://www.jstor.org The Rhetoric of Restraint in Heart of D)arkness JOHN A. MCCLURE The point was in his being a giftedcreature,and that of that carall his giftsthe one that stood out pre-eminently, ried with it a sense of real presence,was his abilityto talk, his words-the gift of expression,the bewildering,the illuminating,the most exalted and the most contemptible, the pulsatingstreamof light,or the deceitfulflowfromthe heartof an impenetrabledarkness. Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness,Part II LTHOUGH MARLOW MAKES A GREAT DEAL of Kurtz's eloquence, he provides only one sure example of Kurtz's public voice -a few fragmentsfrom the report to the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs. Significantly,these few lines bring us close to Kurtz at a moment of moral crisis,when he faces, and succumbs to, the archetypal temptation of the colonial wilderness. Marlow summarizes the report: He beganwith the argumentthatwe whites,fromthe point of developmentwe had arrivedat, "must necessarilyappear to them [savages]in the natureof supernaturalbeings-we approach themwith the might as of a deity,"and so on, and so on. "By the simpleexerciseof our will we can exerta power forgood practicallyunbounded," etc. etc. From that point he soared and took me with him. The perorationwas magto remember,you know.It gave me the notion nificent,thoughdifficult of an exotic Immensityruled by an august Benevolence.It made me tinglewithenthusiasm.This was the unbounded power of eloquence[310] Restraintin Heart of Darkness 311 of words-ofburningnoble words.There wereno practicalhin-ts to themagiccurrent interrupt ofphrases.1 At anotherpoint in the novel Marlow himselfgrappleswith the questionofhisrelationto theCongolese.Like Kurtz,he is tempted to asserttheirabsoluteothernessand inferiority, but he resistsand stumblesthroughto a saving illumination:"The earth seemed unearthly.... It was unearthly, and the men were No, they were not inhuman"(36). Because Kurtzlacks restraint, his speech is eloquent but immoral.A "deceitfulflowfromthe heartof an impenetrabledarkness"(48), it reflects his passionfordomination, Marlow'sspeech,on the otherhand,derivesits powerof illumination fromhis habit of self-restraint. Heart of Darkness explores thesetworhetorics. At firstencounter,Kurtz'seloquent speech may seem to stand in ironiccontrastto his brutaldeeds and the passionsthatinspire them,but a closerstudydisclosesa deep similarity betweenspeech and action. Kurtz'snoble utterancesand his ignoble career are shaped in common by his insatiableappetite. In both speaking and acting,he worksfirstto unbind himselffromconventional restraints-whether syntacticalor social-and then to soar aloft, extendinghis powerovera largerand largersphere.This pattern is most clearlyexemplifiedin the report.Beginningwith argument,thatis withcoherentclausal constructions, Kurtzsoon unbinds himselfand soarsaway on a "magic currentof phrases,"a rushofvagueand eulogisticwords.In thecourseof thismovement a metaphoricalcorrelation("we approach them with the might as of a deity")comesto be takenliterallyin a mannerwhich enables Kurtzto achieveanotherkind of soaring:by the end of the passagehe is thinkingof himselfas a "supernatural"being. This patternof unbindingand soaringappearsto be characteristic of Kurtz'sutterancesin general,or at least of his public ones, for the two other samples of his public voice follow a similar process of development.The Manager quotes Kurtz as saying, "Each stationshould be like a beacon on the road towardsbetter I Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness, ed. Robert Kimbrough, rev. ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1971), p. 51. Subsequent referencesto this edition appear parenthetically in the text. 312 Fiction Nineteenth-Century things,a centrefortradeof course,but also forhumanising,improving,instructing" (33). And thebrickmaker seemsto be echoing Kurtzwhen he declaimssardonically, "We want ... forthe guidance of the cause entrustedto us by Europe, so to speak, higher a singlenessof purpose" (25-26). intelligence,wide sympathies, In both thesepassages,as in thereport,Kurtz'sspeechproceeds froman opening phraseof clausal coherence-a formof verbal restraint-intothe releaseofferedby mere enumeration,with its relaxeddemandsforcognitivecoherence,its invitationto acceleration,and itscapacityforincorporating an endlessstreamof verbal ivory-noble words.One wayto "swallowall the air,all the earth, all the men" (61), Kurtz's speech remindsus, is by "enlisting" themverbally.In Kurtz'scase, this symbolicincorporationforeshadowsnothingless thancannibalism. Kurtz'ssentencesunfold so smoothlynot only because of his penchantforenumeration,perhapsthe simplestof all generative syntacticalpatterns,but also because of his refusalto be interrupted."You don't talk with thatman-you listento him" (54), theRussiansays,and Marlowfindssignsof an evenmoretroubling refusalof dialoguein the report,whereKurtzseemsunable or unwilling to interruptthe currentof his own phrases,even when "practicalhints,"hintsabout conduct,are obviouslyin order.This resistanceto interruption, which gives Kurtz'sspeech its fluency, depriveshimof his capacityforself-deliberation, internaldialogue. Because he lacks thiscapacity,Kurtz can "get himselfto believe anything-anything"(74). Marlow'scommenton the absence of "practicalhints" in the reportpointsto anotherwayin whichKurtz'sspeechis structured and his consciousnessstunted by his lack of restraint.Kurtz's diction as well as his syntaxreflectshis dream of transcendent power. By speakingonly in vague generalities,he createsthe impressionof effortless command;the grandtermshe uses seem to subsumeall meredetails,to reducetheworldto an unproblematic totalitywhich he, Kurtz, both understandsand controls.Thus Kurtz'seloquence,born of thatlack of restraint whichlicenseshis appetite for domination,provides him at once with symbolic experiencesof mastery(in the act of effortless articulation)and with falseimagesof a masteredworld (in the articulatedvision). His eloquence is the product of speech habits which not only enact the dreamof dominationbut also distortrealityto makethe Restraint in Heart of Darkness 313 dreamseem plausible.These habitscontributeto Kurtz'sfall. For realityitselfremainsunmoved by Kurtz's eloquent pronouncements.He maylike to believe thathis aspirationsto moral distinctions and to crudergratifications are reconcilable,but they remain in factantagonistic.Similarly,he may persuade himself thathe is a "supernatural"being,exemptedat once fromthe irrational imperativesof his own passionsand those of externalnature,but thisdoes not make it so. The denial merelyrendershim blind to the dangerof these forcesand impotentto resisttheir appeal. This appeal Marlow rendersby personifying the wilderness, portrayingit as a rhetoricianmore persuasiveeven than Kurtz himself:"the wildernesshad found him out early.. . . it had whisperedto him thingsabout himselfwhich he did not know,thingsof whichhe had no conceptiontill he took counsel with this greatsolitude-and the whisperhad proved irresistibly fascinating"(59). Everywhere,then, Kurtz's "unbounded . . . eloquence" (51) binds him to his appetitesand illusions,and blindshim to reality.The engineof a spurioussoaring,it hastens his fall. If Kurtz's speech is unbounded and soaring,Marlow's is restrainedand probing,a symbolicmanifestationof his ethos of self-restraint. Marlow is an explorer,but a cautious one. In his probingnarration,as in his heroic navigationof the Congo, his progressis frequently tortuous,and the dramaof his syntaxoften: correspondsto thatof his voyage: The broadening watersflowedthrougha mob of woodedislands;you lostyourwayon thatriveras youwouldin a desert,and buttedall day long againstshoals,trying to findthechannel,till you thoughtyourselfbewitchedand cut offforeverfromeverything you had known once. (34) There are,ofcourse,stretches ofsmoothsailing,but in bothspeech and action Marlow tendsto make his way againstthe current:in exploring the Congo, against the river'sflow,in exploringthe meaningof the Congo, againstthe flowof his own impulsesand the impulsesof the languageitself. In fact,Marlow'sfirstwordshave the effectof counteringa very Kurtziancurrentof phrases.The framenarrator,lulled by the 314 Fiction Nineteenth-Century wavesrockingthe Nellie, has soaredaway on a wakingdream of imperialglory: Huntersforgold or pursuersof fame,they[Englishadventurers] all had goneout on thatstream, bearingthesword,and oftenthetorch, of themightwithintheland,bearersof a sparkfromthe messengers had notfloatedon theebb ofthatriverinto sacredfire.Whatgreatness of an unknownearthl. . . The dreamsof men, the seed of themystery commonwealths, thegermsof empires.(4-5) We are on familiargroundhere; the narrator'sdictionand syntax are thoseof Kurtzand the late-Victorian imperialisttraditionhe Like Kurtz,the narratoris addictedto elevateddiction represents. and to heroic cliches; like Kurtz's discourses,his tend to begin withcoherentdeclarationsand thento come ecstatically undone in a rushof enumeration. And once again,the effecton comprehensionis disastrous.The verytextureof the narrator'sdiscourseservesto distracthim from any considerationof the mixed motivesbehind imperialism.The insightof the opening phrase,in which the imperialdrive is ascribedto humanappetitesforwealthand fame,is quicklyobscured as thecumulativepatternof the sentencecarriesthe speakeralong to a more elevatedand gratifying interpretation of imperialistsas "bearersof a sparkfromthe sacredfire."Marlow'snarration,followingas it does almostimmediately, servesto checkthiscurrent of thoughtand to interruptwhateversympathetic reveriesit may have induced in the reader."And thisalso," Marlowinterjects, as if intuitingthe narrator'sstateof mind,"has been one of the dark places of the earth" (5). In the storythat followshe deliversa devastatingrebuttalto the narrator'sdreamof benign expansion. as I have suggested,what mightbe called a And he exemplifies, rhetoricof restraint. What Marlow restrains,basically,is the desire for comforting he resiststhe solutions,conclusions,certainties.More specifically, impulse to achieve, throughthe curtailmentof debate and the a falseimpressionof resolution. fashioningof eloquent utterances, One of Marlow'sbasic strategiesforcombatingthe "bewildering" currentsin his own voice is to carryover the processof discovery, a momentpriorto delivery,into his narrativeitself, traditionally so thatthe act of deliverycomes to partakeof the murkyconfusionsand flashingilluminationsof exploration.Here, forinstance, Restraint in Heart of Darkness 315 is Marlow'sdescriptionof the manager'spower: "He was obeyed, yethe inspiredneitherlove nor fear,nor evenrespect.He inspired uneasiness.That was it! Uneasiness"(22). What is offeredhere is both a descriptionand the processof its discovery, the searchfor the properlexical channelby whichto reach the truthof the experience.But by importingthe searchfor le mot juste into his narrative,Marlow does not signal his own total victoryover the temptations and limitationsof language;he onlyalertsus to their tesexistence,and to the necessityforstruggle.In fact,his efforts tify,as criticssuch as J. Hillis Miller have observed,to the difficulty,perhapseven the impossibility, of doing justice to experience withwords.2 Moreover,by importingdiscoveryinto the act of narration, Marlow depriveshis speech of fluencyand the authorityit confers;whereas Kurtz's "finished"voice repels interruption,Marlow's provisionalutterancesinvite it. On several occasions,his narrationis interruptedby the audience aboard the Nellie, but the mostfrequentintrusionsare by Marlowhimself.While Kurtz allows nothingto checkthe flowof his phrases,the currentof his dreams,Marlowinterrupts himselfconstantly, to questionthe appropriatenessof a word, to revise an image, to reject an entire interpretation. He setshisvoice againsthis voice,his visionagainst his vision,so thatat timeshis narrativeresemblesa collaborative effortof severalmen tryingto reconstructa shared experience, and has the same ragged textureas such a discourse.Richard Poirier'sportrayalof the modernistauthor'sexperienceof articulation describes Marlow's practice precisely: in reading what theyhaveproduced,Poirierobserves,modernist writersseemto feel only the necessityof alternativeconstructions, the pressingobligationto revise,qualify,or contradictwhattheyhavejust written.3 Marlow'sneed to contradictand revisehis own utterancesbecomes increasingly strongas he getsdeeper into his narrativeand into the Congo. In the firststagesof his narration,his speech is ofteneasyand colloquial, seasonedwithexpressionsthatnot only carrythe storyforwardbut remindus as well of the conventional quality of much discourse,its foundationin shared experience and attitudes.Littlechapsget "a hankeringafter"exploration;the 2 3 Poets of Reality (1965; rpt. New York: Atheneum, 1974). The PerformingSelf (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1971), pp. 11-12. 316 Nineteenth-CenturyFiction Congo is "a mightybig river,"and men win positions"by hook familiar or by crook" (8). Familiar phrasesevoke a comfortingly world. But gradually,as Marlow'snarrationcarrieshim back into the rememberedshocksand confusionsof his experience,his speech loses its conventionalquality.Marlowis troubledboth by his own inabilityto understandhis experiencefullyand by the difficulty of makinghis audience see even the partof it whichhe can comprehend.The journeyto Africatakeshim beyondthe geographical boundariesof his language community,into a world whose featuresno longer correspondto the images conveyedby the European words he has for them. Thus, he sometimesoffersa word only to retractit: "the earthseemed unearthly"(36). For Marlow,and forhis audience,the word "earth" evokesan image of the English countryside,and carrieswith it the sense of a certainrelationbetweenmen and the land. But whathe has seen, and whathe wantshis audience to see, is somethingverydifferent: a tangledand malevolentchaos ofgrowingthings.To comprehend and conveyhis meaning,he mustbecome more specificand concrete.His firstresponseis the simple,thoughqualified,negation; and throughcomparithenhe developsthe distinctionfiguratively son and contrast.The English earth is "the shackledformof a conquered monster,"the Congo earth "a thing monstrousand free"(36). Withoutdenyingall identity, he insistson the essential which are easilyobscuredby abstractlandifferences differences, cast doubts on the Englishguage,and which,when confronted, man's assumptionthathe mayeffortlessly extendhis rule-cognitiveand political-to the Congo. In an incidentwhich Marlow recountslater in the narrative, the potentiallyfatalconsequencesof imposingconventionallabels worldbecomeclear: Marlow,concentrating on an unconventional word "sticks"to identifythe thingsflying uses the on navigation, about his cabin. In his nativeuniverseof discoursesuch an identificationis natural. But these "sticks"come fromoutside that on navigation,does universe,and because Marlow,concentrating he makes notrecognizethedisjunctionand adjusthis expectations, himselfa finetargetforAfricanarrows.His awakeningis in the comic traditionof thosemomentswhen the explorerrealizesthat he has indeedsucceededin crossingtheborderintoan alien world, Restraintin Heart of Darkness 317 and has done so withoutadjustinghis own world view: "Arrows, byJove!We werebeingshotat!" (45). Thus the feltneed to recognizehis distancefromthe familiar and to apprehendand communicatethe difference it makesforces Marlow towardsspecificityand figurativelanguage: arrowsare sticksof a sort(just as the Congo soil is earth),but it is the differentiationthatis significant when thatsortof stickis whizzingpast your head. In contrastto Kurtz's consistentlyelevated diction, then,Marlow'sis oftenmuddywithspecificity. When he does use abstractions,as for instancewith those abstractadjectives ("inscrutable," "inconceivable," "unspeakable") that F. R. Leavis findsso unsatisfactory,4 it is usually in order to emphasizethe limitsof vision and the difficulty a new world of comprehending in the termsof the old. Leavis himselftestifiesthat the words convey this message-"the actual effectis not to magnifybut ratherto muffle"5-butdoes not seem to realize that the muffled qualityof existenceis an essentialpartof the moralexperienceof Heart ofDarkness.The need to conveya trueimpressionentangles Marlowin murkyparadoxes,franticsearchesforthe correctword; it breaksthe flowof his prose.But the effectis to discoverimportantdistinctions obscuredby language,and to alert the readerto, of purelyverbalcomprehension. the deceptiveness In these severalways,Marlow's cautious use of language generateswhat mightbe called a syntaxof uncertainty. The drama enactedby manyof his sentencesis one of probingexploration, prolongedfrustration, provisionalilluminations.This is not always the case, of course-some passagesmove forwardsmoothly and authoritatively. But as Marlow pushes on into the heart of his narrative,his sentencescome increasinglyto turn back on themselves in the mannerdescribedby FrancisChristencritically, sen in his definitionof the cumulativesentence.The main clause, Christensen observes, "exhausts the mere fact of the idea. . .. The additionsstaywiththe same idea, probingits bearingsand impliit or seekingan analogyor metaphorforit, cations,exemplifying or reducingit to details."6In some cases,Marlow'sadditionshave an even more radical impact on the original formulationthan 4 The Great Tradition (1948; rpt. New York: New York Univ. Press, 1963), p. 177. 5 Ibid. 6 Notes Toward a New Rhetoric (New York: Harper and Row, 1967), p. 6. 318 Nineteenth-CenturyFiction Christensen'sdescriptionsuggests;ratherthan "stayingwith it" in the conventionalsense, they turn against it dialectically,revealing its one-sidedness.The followingsentence,for instance, challengesthe conventionalidea firstevokesand thendramatically of jungle drums: "Perhaps on some quiet night the tremorof far-off drums,sinking,swelling,a tremorvast, faint; a sound weird,appealing,suggestive,and wild-and perhapswith as profound a meaningas the sound of bells in a Christiancountry" (20). The firstadditionsto the base clause deepen the aural image with its connotationsof exoticsavagery;theybuild to the climax of "wild." But then the sentencebreakssuddenly,with the dash, and the simile which followsoffersan antitheticalinterpretation of the drums.What the dash indicatesis an abrupt shiftin perspective,as Marlow stopsrespondingto the drums in a conventional mannerand puts himself,as much as he can, into the culof whichtheyare a part. turalframework The result of this achievementis an ungainlysentence,one which violates the verysyntacticaland cognitivecurrentsit sets in motion. But the cognitivebreakthroughmore than compensates for the stylisticbreakdown;by probing his topic at such length-long past the last graceful"and," beyond the limits of standardsyntax-Marlowreachesthatdialecticalpoint wherethe object of observationshiftsand reveals its other face, or where the observernoticesthe limitsof his own articulatedperspective and allows another perspectiveto suggestitself.By restraining himselffrorm passingquicklyover thisdescriptionof the drumsone ofthemostclichepropertiesof theAfricanset-Marlow penetratesbeyondthe superficialexoticismtheyare so frequentlyused and seesthemfrombehindthe screen,fromwithinthe to register, world of which theyare a part. The moral significanceof his achievementis immediatelyevident: interpretedconventionally as signsof the savageryof the Africans,the drumscan be used to justifytheirsubjugation.But when it is recognizedthatthe sense of wildernessthe drumsevokeis due to the positionof the European observer,and thattheirrole withinthe Africanculturemay to put an end to the be as symbolsof relationship,thenany effort drummingbecomesan attack,not on anarchy,but on community. Earlierwe saw how Marlow,probingtheword"earth,"recognized and overcamethe spuriousidentitywhich it imposed on signifi- Restraint in Heart of Darkness 319 cantlydifferent landscapes.Here we see him resistinga too easy oppositionof "savage"Africanto "civilized"Europe. of Marlow'srestraintbecomesclear when The full significance he addressesthe issue of his relationto the Congolese. Kurtz,as we have seen,uses his eloquence to persuadehimselfthatthereis betweenhis own race and the an absolute,ontologicaldifference Africans;he denies any kinship,and so, implicitly,any need for the restraintwhich kinship traditionallyentails.When Marlow facesthe same question in his own "report,"he too is tempted to denykinship.But, as we have seen,he resists: The earthseemedunearthly. We are accustomedto look upon the but there-thereyou could shackledformof a conqueredmonster, and free.It was unearthly, look at a thingmonstrous and the men were- No, theywerenotinhuman. (36) At thisdecisivemomentmanyforcesare thrusting Marlowtowards At the denial,but one of the mostobviouspressuresis syntactical. beginningof the passageMarlowfallsinto patternsof balance and antithesis;by the end,theimpulsiontowardsa balancedresolution is tremendous.Once again Conrad employsdashesto indicatethe momentwhen Marlow,listeningcriticallyto the unfoldingof his own discourse,feelscompelledto checkitsflow.Refusingtheclaim to absolutesuperiority explicitin the meaningof his unfinished sentenceand implicitin its potentiallyperfectstructure, Marlow drawsup, acknowledgesthe galling truthof kinship,and speaks it. At themoralcrisisof his adventurehe confronts and overcomes the appetiteforstylistic perfection. But while Marlow'srestraintenableshim to use languagemore successfullythan Kurtz as a vehicle of verbal explorationand illumination, at thesametimeit preventshim frompursuingmore concreteexplorationsas faras Kurtz does. A manuscriptpassage deleted fromthe publishedversionsof Heart of Darknessasserts thatcomprehensionof an alien world can only be achieved "by conquest-or by surrender."7 Marlow,committedto an ethos of 7 Conrad, Heart of Darkness,ed. Kimbrough,p. 36n. The manuscriptitselfis in the Yale UniversityLibrary. 320 Fiction Nineteenth-Century wishesneitherto dominatethe Africansnor to surself-restraint, their ways.He wantsinsteadto preservedistanceeven renderto in the processof exploration:"An appeal to me in this fiendish row-is there?Verywell; I hear; I admit,but I have a voice too, and forgood or evil mine is the speech thatcannot be silenced" (37). While Marlowlistensacrossdistanceforclues to the alien existenceof theAfricans,Kurtz,persuadedof his own invulnerability and of the rectitudeof his project,plunges headlong into the passional wilderness.Surrenderingto appetite,he sinks deeper into delusion and depravity,until he is beyond return,cut off irrevocablyfromany social salvation.The atrocitieshe commits in the courseof his fall confirmthe soundnessof Marlow'sethos; a man becomesan enemyboth to himself withoutself-restraint, and to others. Yet Kurtz'sheadlongdriveissuesultimatelyin an illumination unobtainableto Marlow.The Africans'criesremainfor Marlow "stringsof amazing words that resembledno sounds of human intelligibleto Kurtz: "Do you language,"but theyare perfectly understandthis?" Marlow asks. "Do I not?" Kurtz replies (68). whichhe sees as conquest,enableshim to Kurtz'sblind surrender, thatMarlowis unable to penetrate;he obcomprehendmysteries tains,at the expense of a kind of culturaland moral suicide, an understandingof the language of the place, and hence, perhaps, a deeperknowledgeof the place itself. As in thisfigurative suicide,so in death itself,Kurtzachievesa inaccessibleto the more cautious Marlow. level of understanding His finalwords,"The horror!the horror!"(71), stand in stark contrastboth to his earlierutterancesand to Marlow's"inconclusive" (7) mode ofnarration."He had summedup-he had judged" at summaryand judg(72), exclaimsMarlow,whose own efforts And Marlow suggeststhat it is Kurtz's ment are ever frustrated. in somewaysso fatalto vision,whichhas enabled lack ofrestraint, him to speak with such authenticeconomyand authority.Kurtz can speakas he does because "he had made thatlast stride,he had steppedover the edge,while I had been permittedto draw back no matterhow my hesitatingfoot" (72). Ultimatelyself-restraint, mingledwiththe kind of audacitythatleads a man to set out, as Marlowdoes, to explorethe heartof darkness,imposeslimitsthat Restraint in Heart of Darkness 321 self-assertion need not honor.And if self-assertion goes equipped, as Kurtzdoes, with talentand ideas, it mayhave,at whateverexpense,the finalword. Marlow'sethos impairshis speech in anotherway as well. His resistanceto the deceitfulcurrentsin the language,whileenabling him to use speechas a tool of discovery, makeshis narrationhard to follow.Heart of Darkness,a novel of speakers,is also one of and thedepressing listeners, factis thatKurtz'sunboundedrhetoric capturesand holds the wideraudience,includingtwo of the most worthylistenersin the novel, the Intended and the young Russian. Kurtz'spoweroverhis fianceeis at leastpartlyrhetorical:"Who was not his friend,"she asks,"who had heard him speak once?" (77). Marlowchoosesnot to challengethatpowerboth because he is yetunsurewhetherhe himselfcan live withthe disillusionments of his experience,and because he has no faithin women'sability to live withthe truth.Hence it is withthe Russian,Kurtz'sother European disciple, that the test comes, albeit indirectly.The youth,despitehis motley,is a worthyaudience,inquisitive,persistent,humble. He loves books,and even has the Conradiansense of the purpose of discourse:Conrad's famous "My task . . . is ... to make you see,"8is echoed by the Russian's "He made me see things-things"(56). Of all the audiences in the novel, the Russian is the mostattractive. But the "he" to whom the Russian refersin the passagecited above is Kurtz, not Marlow. The Russian surrendershimself completelyto Kurtz,and worshipshim as a divine being. He responds,as do others,to Kurtz'sethos of infallibility, and to the dramaof transcendence inscribedin the verysyntaxof his speech. This surrendercannot be seen as due to the Russian's ignorance of the alternativestance,forby the timehe meetsKurtzhe is alin a holybook, Towson's Inquiry,whichhe has readywell-versed annotatedextensively. The Inquiry is a kind of Conradianbible, as the verymodestyof the title and Marlow's brief description make clear.The text,"luminouswithanotherthana professional light,"is an earnestprobing "into the breakingstrainof ships' 8 Joseph Conrad, The Nigger of the "Narcissus" (1898; rpt. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page, 1924), p. xiv. 322 Fiction Nineteenth-Century It bears chainsand tackle"(38), thatis, into the limitsof restraint. a curiousresemblancethen,not only to a holy book, but also to Heart of Darknessitself,with its analogous inquiryinto human breakingstrains.By readingit so closely,the Russiandemonstrates his basic soundness;by abandoningit to followKurtz,he attests to the relativeweaknessof its appeal. The pessimisticimplicationsof the Russian's apostasybecome even deeper when we considerthe similaritybetweenhis history and Conrad's own: "he had run away fromschool,had gone to sea in a Russianship; ran awayagain; servedsome timein English ships" (54). By creatingthe Russian so much in his own image, Conrad seems to have writtenhimselfinto the novel in the role of a worthyaudienceforthe rhetoricalstruggle,and then to have deliveredhimselfinto the hands of the more eloquent but less illuminatingspeaker.In a sense,he offerstestimonyagainstthe appeal of his own nature,voice, and vision. And if we consider the parallelsbetweenthe Inquiry and Heart of Darkness,the implicationsbecome even more oppressive:the youngConrad reads the older Conrad'swork,but abandonsit to surrenderhimselfto a tyrannicaldemagogue.Of course,there is no way to "prove" the validityof such a reading,and it would be foolishto equate thepersuasivevalue of a maritimehandbookwiththatofHeart of Darkness.But it is clear,I think,thatthe Russian'schoice is for the values embodied by Kurtz,and againstthose which Marlow represents.Marlow himselfmakes only the feeblesteffortto dissuade the youthfromhis infatuation,but he does send him off equipped once again withTowson's text. Thus Marlowmakesno convertsamongthosewho havebelieved in Kurtz,and acquiresno audience of faithfuldisciples.He has, and theseare doubtfulones. in fact,onlya fewrhetoricalvictories, The framenarrator,throughlong experienceof Marlow'sstories, has come to know how to attendto them.He is readyto listen carefully:"I listened,I listenedon thewatchforthe sentence,for the word,thatwould give me the clue to the faintuneasinessinspiredby thisnarrative"(28). And he is reconciledto the provitheir"inconclusive"quality (7). sionalityof Marlow'srenderings, Thus prepared,he seemsto receiveMarlow'smessageclearly,for his earlyvision of the Thames as a channel of light and of the imperialmissionas an unquestionablegood has givenway by the Restraint in Heart of Darkness 323 end of Marlow'stale to a farmoresomberview in whichthe river "seemedtolead intotheheartofan immensedarkness"(79). There are signs,too,thattherestof Marlow'saudiencehas been similarly moved,forno one has noticedthetide changing.But theaudience is a tiny,isolated one of close friends,a brotherhoodof men privileged,in Conrad's eyes,by a shared experienceof the sea. There is littlesuggestionthatMarlow can hope to communicate his discoveriesto the"commonplaceindividuals"(72) in the "monstroustown" (5), whichis his civilization'scenter. Herein lies the ultimateironyof Heart of Darkness.Perhaps only thosediscoverieswhichare in factexpressionsof what is alreadyknownor feltcan be communicatedto themassofmen,since genuine discoveriescreate the need for new patternsof speech and understanding, and theseare establishedonlyundergreatpressure (as in the Congo) or withgreatlabor. A rhetoricof restraint or one restrainedby cirrequiresan audiencecapable of restraint, cumstance,like the men on theNellie. Thus the contestbetween Kurtz's unbounded, impositionalstyleand Marlow's restrained, inquiringstyleendsin a grimstalemate:Marlowattainsthesaving insights,Kurtzthe audiencesin need of enlightenment. Marlowdoes win one significant rhetoricalvictory,but only by a moral compromisewhich transforms his voice. When Kurtz, safelyaboard thecompany'sboat, triesto returnto thewilderness, Marlow followsand attemptsto counter its appeal: "I tried to break the spell-the heavy,mute spell of the wilderness-that seemed to draw him to its pitilessbreast"(67). Kurtz has made himselfso much the measureof all things,however,thatMarlow's onlyrecourseis to appeal,as thewildernessitselfhas, to his dream of power: "'Your successin Europe is assuredin any case,' I affirmedsteadily"(67). Only by a steadyaffirmation of a deceiving dream,only,in otherwords,by imitatingKurtz'sown voice,does Marlowsucceedin breakingthespell of thewilderness.In uttering this firstsaving lie, he attestsindirectlyto the limitationsof a rhetoricof restraint. Yet thereare elementsof ambivalencein Heart ofDarknessthat make the qualifiedtriumphof Kurtz'svoice less appallingthan I have suggested.Marlow and Kurtzare by no means simplyantitheticalfigures;both are classifiedby the brickmakeras members of "the gang of virtue" (26), and Marlow, given his "choice of 324 Nineteenth-CenturyFiction nightmares"(63), commitshimselfto Kurtz. From a rhetorical perspective,the essentialbond betweenthe two men is thatboth acknowledgein theirdiscoursethe existenceof moral imperatives that transcendthe imperativesof the universeof commerce.For Kurtz,of course,thereis a fataldisjunctionon preciselythispoint betweenrhetoricand action,but by usingethicalterms,no matter how inauthentically, he preservesthememoryof a set of standards beyondself-interest and expediency,a set whichhe ultimatelyemploysto judge himself. In contrastto both Kurtzand Marlow the otherEuropeansin the Companyspeak a languagedevoid of all moral referencebeyond the immediateimperativesof commercialprofitand loss. Even in the face of Kurtz'srevelationof the cannibalistictelos governingcommercialactivity,their discourse remains "valuefree": The managercameout...... "thereis no disguising thefact,Mr. Kurtz has done moreharmthangood to the Company.He did not see the timewas not ripe forvigorousaction.. . . look how precariousthe positionis-and why?Because the methodis unsound.""Do you," said I, lookingat the shore,"call it 'unsoundmethod'?""Without doubt,"he exclaimedhotly.. . "It is mydutyto pointit out in the properquarter." (63) The manager'sspeechexemplifies the techniquesby whichcertain acts of criminalinsanity-thosewhich expressthe inherenttendenciesof powerfulinstitutions-aremade to seem less atrocious, morerational,and less emblematicof thewhole thantheyactually are. The managerconcealstheappallingbrutalityof Kurtz'sdeeds by describingthemin a singleabstractphrase,"vigorousaction," whichcarriesfaintlyeulogisticconnotations.And he concealsthe moral viciousnessof the same deeds, their foundationin "monstrouspassions"(67), by excludingmoral termsfromhis universe of discourse.By criticizingKurtzin purelyinstrumental terms"unsoundmethod"-he implicitlydeniesthevalidityofanymoral critiqueof Kurtz'smotives,and by extensionthoseof all imperialists.A situationthatrevealsthe evil of the entireenterprisecan thusbe dismissedas a mere matterof bad businesspractice,and themanagercan go on "cautiously"(63) exploitingand murdering Africans. Restraint in Heart of Darkness 325 Reactingagainstthemanager'sbrutallyreductiveinterpretation, Marlowturns"to Kurtzforrelief"(63), and so has theopportunity judgmentpronouncedby Kurtz to hear another,more satisfying of Kurtz'svoice to thatof the pilgrimsis himself.The superiority demonstratedby Kurtz's finalwords,in which he passes moral judgment on himselfand wins a "moral victory"(72). Kurtz, unlike the pilgrims,has at least the wordsby whichto judge; his discoursehas kept alive the tribunalbeforewhich self-flattering he ultimatelydeclareshimselfguilty. For this reason alone, it mightbe argued that the power of Kurtz'svoice to win disciplesis not altogethera cause fordespair, amoral unisince his rhetoricpreserves,againstthe aggressively the verseof commerce,at leastthe foundationsfora reassessment, memoryof a higherstandardforconduct.In fact,Heart of Darkness hints,Kurtz'svoice may preservetheseessentialvalues more than Marlow'sown. For Marlow'ssyntax,by its very successfully dynamic,perpetuallyuncoversuncertaintiesand contradictions, and hence encouragesa restraintakin to despair,ratherthan the hope whichmust underlieactive engagementwith the world. In the end, though,Conrad chooses to speak throughMarlow,and so seems to suggestthat it is his rhetoricof restraintwhich deserves,in a timeof unbounded imperialexpansion,attentionand emulation. his Studiesof Marlow'sstylehave tendedto see it as reflecting and Conrad'ssense of the disparitybetweenlinguisticformsand J. Hillis Millerobserves, ofreality.Marlow'srhetoric, thestructure calls attentionto the "gap betweenwordsand the darknessthey can neverexpress";9and JamesGuetti also stressesthe themeof linguisticinadequacyimplicitin Marlow'sstyle,whichhe calls a "rhetoricoffailure."'0My commentshavebeen intendedto extend I have suggested,have theseinsights.Marlow'sverbalfrustrations, roots.Part of the distancehe feels moral as well as metaphysical betweenlanguageand the worldis the resultof his own decision for restraint,his unwillingnessto learn the language of the passions. This unwillingnesscondemnshim to an inconclusiveness which Kurtz,finally,seemsto transcend. 9 Miller, p. 36. 10 The Limits of Metaphor (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univ. Press, 1967), p. 9. 326 Nineteenth-CenturyFiction But Marlow's sense of the distancebetweenwhat is and what can be said is not the onlyfactorcontributingto his cautious,inin conclusivestyle.By emphasizingthe elementof self-restraint Marlow'saction and speech,and the antitheticalquality of selfprojectionin Kurtz's,I have soughtto shiftattentionfromthe shapinginfluenceof the darknesswithoutto thatof the darkness within.Marlow senses-and his intuitionis confirmedby the example of Kurtz-that the forcesof this psychologicaldarkness, man's "unlawful"(67) appetitesand dreams,can easily"capture" man's speech.And he realizes,again partiallythroughhis experiences with Kurtz, that when these impulses are allowed unrestrainedexpression,the utteranceswhich resultonly compound the darknessin which men alreadymove, only increasethe gap betweenwordsand the worldtheymightotherwiseilluminate.It is Marlow'shabitual vigilanceagainstthe tyrannyof these inner impulses,as muchas his continuingawarenessof the gap between wordsand reality,thatmakeshis speechso demandingand allows him to see so deeplyinto the darkness. UniversityCollege,RutgersUniversity