Injury, Int. J. Care Injured (2004) 35, 963—967

Ocular injuries caused by plastic bullet shotguns

in Switzerland

Florian K.P. Sutter*

Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital Zurich, CH-8091 Zurich, Switzerland

Accepted 11 November 2003

KEYWORDS

Blunt ocular injury;

Blindness;

Plastic bullets;

Rubber bullets;

Sub-lethal weapons;

Ballistics;

Baton rounds;

Riot control

Summary Five patients with blunt ocular trauma due to hard plastic shotguns used by

police forces during riots presented to the Ophthalmology Department of University

Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, between December 2000 and May 2001.

All five eyes suffered ocular concussion. Three of five eyes presented with severe

damage to the anterior segment of the eye, two of these eyes showed combined

involvement of the anterior and posterior segments. Two patients completely recovered their visual acuity in the injured eye, two reached a final visual acuity of 6/12 and

in one case the injured eye was legally blinded. Three of the patients claimed to have

been uninvolved bystanders at the riots. The theoretical probability of hitting the

head/neck area or one of the two eyes for each shot fired at a person from different

operational distances is calculated and ophthalmological and technical aspects of this

special type of plastic bullet shotgun used in Switzerland are discussed.

ß 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

For many years, police forces around the world have

used rubber and plastic bullets to control rioting

during political demonstrations and civil conflicts.

These fire weapons of ‘‘reduced power’’ aiming to

inflict blunt trauma in order to immobilise or ‘‘neutralise’’ the targeted persons. They are not

intended to kill. Initially wooden projectiles were

used in the 1950s and 1960s.9 In 1970 single shot

rubber bullets were introduced in Northern Ireland.2 These ‘‘baton rounds’’ are generally directed

to the lower part of the body, but due to flight

instability their aim has shown to be inaccurate.9

Impacts upon vulnerable body parts such as the

face, head and neck causing severe injuries or even

death have occurred.6 Rubber bullets have since

been replaced by hard plastic projectiles which

*Tel.: þ41-1-255-11-11.

E-mail address: sutter-adler@gmx.ch (F.K.P. Sutter).

were designed to offer more accurate aim without

causing more damage than their predecessors.4,7

However, as a number of projectiles have been

developed and used in different countries there

have been a varied array of subsequent injuries

reported.1,2,5,11 Injuries to vulnerable upper body

structures have proven to be the most serious.6,8,10

Materials and methods

Between December 2000 and May 2001 five patients

with blunt ocular trauma due to plastic bullets

presented to the University Hospital of Zurich,

Switzerland.

Results

All patients were male (age range 19—46 years). All

five eyes involved showed signs of ocular concussion

0020–1383/$ — see front matter ß 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.injury.2003.11.020

964

F.K.P. Sutter

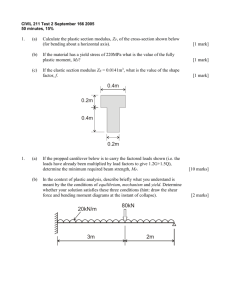

Figure 1 Slit lamp image of the anterior segment 2 h after blunt ocular trauma due to a plastic bullet showing

conjunctival injection, descemeth’s folds, traumatic hyphema and fibrinous anterior chamber reaction (a). Fundus

image of the same eye 3 months later showing a large macular and retinal folds (b) causing loss of central vision and

legal blindness.

with anterior chamber cells and flare. Three of five

eyes presented with severe damage to the anterior

segment of the eye involving the iris (sphincter

rupture), the anterior chamber angle (angle recession/irido- and cyclodialysis/traumatic glaucoma)

and/or the lens (traumatic cataract). Two of these

eyes showed combined involvement of the anterior

and posterior segments with vitreous and retinal

haemorrhage, peripheral retinal tears or central

macular scaring (Fig. 1a and b).

Two patients completely recovered their visual

acuity in the injured eye, two other patients

reached a final visual acuity of 6/12 and in one case

the injured eye was legally blinded. One patient

with combined anterior and posterior segment

involvement who reached a visual acuity of 6/12

on day 1 was subsequently lost to follow-up. Three

of the patients claimed to have been uninvolved

bystanders at the riots. Relevant clinical data are

summarised in Table 1.

Ocular injuries caused by plastic bullet shotguns in Switzerland

965

Table 1

Type of injury, follow-up and final visual acuity

Patient

Sex

Age

Firing

distance

Injury: ocular

concussion with

Procedures and

Follow-up

1

M

21

20—30 m

Six surgical

interventions

6/12

2

M

23

Unknown

Lost to follow-up

6/12

3

M

46

>20 m

4

M

19

Unknown

5

M

21

Unknown

Traumatic cataract,

iris sphincter rupture,

traumatic glaucoma

Corneal erosion,

vitreous haemorrhage

Iridodialysis, cyclodialysis,

hyphaema, vitreous haemorrhage,

ocualar hypotony, optic disc

oedema and macular scar

Iris sphincter rupture, angle

recession, retinal oedema,

retinal haemorrhage,

peripheral retinal tears

Anterior chamber cells and flare,

no haemorrhage

No surgical

interventions

Final Visual

Acuity

<6/60

(legally blind)

Retinal laser

coagulation

6/6

No surgical

intervention

6/6

Discussion

In Switzerland a special type of shotgun with hard

plastic bullets has been used since 1981. A total of

35 hexagonal PVC-cylinders of 11 g each, wrapped

in a plastic foil (Fig. 2a), are fired from a shotgun

(Fig. 2b). After leaving the rifle with a muzzle

velocity of 200 m/s, the plastic foil ruptures and

the projectiles reach their goal as buckshot. At an

operational distance of 20 m these projectiles are

scattered almost randomly over a surface area of

2 m in diameter (and for operational distances of 10

and 5 m, 1.5 and 1.0 m in diameter, respectively)3

(Fig. 3).

Due to the scatter of these plastic bullets, it is

impossible to avoid hits to the head and neck.

Figure 2 Type of plastic bullet shotgun used in Switzerland. Thirty-five hexagonal PVC-cylinders of 11 g each,

wrapped in a plastic foil (a), are fired from a shotgun (b).

Figure 3 Random scattering of plastic bullets fired at a

target from 20 m (a), 10 m (b) and 5 m (c)3 (Courtesy

of: Geschäftsprüfungskommission des Gemeinderates

Zürich).

0.0234

0.0411

0.0898

0.347

0.532

0.822

0.038

0.038

0.038

0.00106

0.00106

0.00106

3.14

1.77

0.79

2.0

1.5

1.0

20

10

5

Operational Cone of dispersion:

distance (m) diameter (2r) (m)

Cone of dispersion:

surface (A ¼ pr2 ) (m2)

Surface of one orbit

(3:0 cm 4:5 cm)

(O ¼ abp) (m2)

Surface of head and neck

area approximately

(F ¼ ðabpÞ þ ðwhÞ) (m2)

Probability for hits to

Probability for hits to

head and neck area

one of the two eyes

(PH ¼ 1 ððA FÞ=AÞ35 ) (PE ¼ 1 ððA 2OÞ=AÞ35 )

F.K.P. Sutter

Table 2 Data and formulae used for the calculations of the probability for hits to vulnerable areas (head/neck; eyes)

966

Assessing the theoretical risk of the weapon

involves calculating the mathematical probability

of at least one of 35 projectiles hitting a surface

equal to the surface of the head/neck area (or the

surface of the eye area) within the cone of dispersion. This can be calculated for different operational distances (assuming that the plastic

projectiles are scattered randomly). The formula

and data used for the calculations are shown in

Table 2. Because these calculations are approximate, the numbers have been rounded.

At an operational distance of 20 m the probability

of each shot aimed towards a person hitting their

head or neck is 35%. About 2% of the shots can be

expected statistically to hit one of the two eyes. At

a shooting distance of 10 m the risk increases with a

50% chance of hitting the head/neck region and 4%

chance of hitting the eye(s). At 5 m these risks

increase again to 80 and 9%, respectively.

Ocular injuries are of particular consideration as

the small single plastic bullets fit well into the

opening of the orbit thus transmitting large concussive forces to the eyeball.

Conclusion

The projectiles of hard plastic bullet shotguns used

for riot control in Switzerland show a considerable

risk of injury to vulnerable body parts such as the

head, neck and eyes. From our clinical observations

and theoretical calculations we conclude that, from

an ophthalmological/medical point of view, independent of political bias, this weapon is potentially

harmful. Perhaps its use should be reconsidered

during times of peace. Furthermore, the risks of

shotguns compared to single shot guns should be

taken into account for the development of sublethal weapons.

References

1. Balouris CA. Rubber and plastic bullet eye injuries in

Palestine. Lancet 1990;335:415.

2. Cohen MA. Plastic bullet injuries of the face and jaws. S Afr

Med J 1985;68:849—52.

3. Geschäftsprüfungskommission des Gemeinderates, Einsatz

der Stadtpolizei bei den Auseinandersetzungen vom 1. Mai

1996. Stadt Zürich 1997;144.

4. Metress EKSP Metress, The anatomy of plastic bullet damage

and crowd control. Int J Health Serv 1987;17:333—42.

5. Missliwetz J, Wieser I, Denk W. Medical and technical

aspects of weapon effects. IV. Plastic bullets reduce the risk

of the military assault rifle (StG 77). Beitr Gerichtl Med

1991;49:361—6.

6. Ritchie AJ. Plastic bullets: significant risk of serious injury

above the diaphragm. Injury 1992;23:265—6.

Ocular injuries caused by plastic bullet shotguns in Switzerland

7. Rocke L. Injuries caused by plastic bullets compared with

those caused by rubber bullets. Lancet 1983;1:919—20.

8. Shaw J. Pulmonary contusion in children due to rubber

bullet injuries. Br Med J 1972;4:764—6.

9. Sheridan SMRI Whitlock. Plastic baton round injuries.

Br J Oral Surg 1983;21:259—67.

967

10. Whitlock RI. Charles Tomes Lecture, 1979. Experience

gained from treating facial injuries due to civil unrest.

Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1981;63:31—44.

11. Yellin A, Golan M, Klein E, Avigad I, Rosenman J, Lieberman

Y. Penetrating thoracic wounds caused by plastic bullets.

J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1992;103:381—5.