Journal of Learning Disabilities

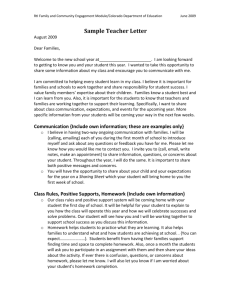

advertisement