Sport Colonialism and United States Imperialism

advertisement

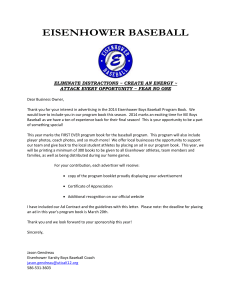

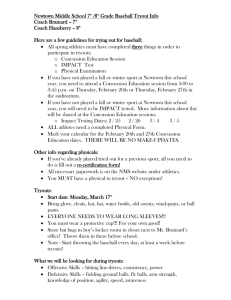

SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM FORUM Sport, Colonialism, and United States Imperialism GERALD R. GEMS Department of Health and Physical Education North Central College B Y 1914 EUROPEAN POWERS, LED BY GREAT BRITAIN, France, and Germany, controlled 85 percent of the earth’s land surface. By that time the United States, itself a former colony, had become a major player in the imperial process. Over the past century a number of American historians have glorified such expansionism as a heroic struggle, a romantic adventure, a benevolent mission, and a Darwinian right or inevitability. In doing so, they constructed (some might say invented) national identities.1 Only more recently, since the 1960s, have scholars questioned imperialism and its practices. Post-colonial scholars, such as C.L.R. James, and revisionist historians have used a more critical lens, sometimes from the perspective of the conquered and colonized. James’s influential Beyond a Boundary (1964) assumed a Marxist paradigm in its investigation of the role of cricket in the process of subjugation. Most other analyses have taken similar theoretical perspectives. Over the past dozen years, British historians, led by J.A. Mangan, have conducted a thorough examination of the role of sports and education in cultural imposition. American and European scholars, however, have not kept pace. Allen Guttmann’s Games and Empires (1994) remains the only comprehensive American study, while Joel Franks has published two recent inquiries into cross-cultural sporting experiences in Hawai‘i and the Pacific. Joseph Reaves’s Taking in a Game: A History of Baseball in Asia (2002) is a welcome addition to this short list. Murray Phillips offers a useful critique of newer work in his “Deconstructing Sport History: The Postmodern Challenge.”2 Historians and, more recently, sport historians have clearly identified particular elements of the imperial process. Integral to this ideology is the concept of race, a nineteenth-century construct that embedded social class, religious, and gender connotations Spring 2006 3 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY and accorded certain rights and privileges. Scholars have coined the term “whiteness,” but the concept goes beyond skin color to include intellectual and physical capabilities. As the Darwinian scientific revolution of the mid nineteenth century drifted into pseudosciences, such as physiognomy and phrenology, biological theories purported to rationalize ethnic “differences.” Already established stereotypes became rationalized, justified, and entrenched. British and American scientists who constructed such racial, ethnic, and religious pyramids inevitably placed white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant (WASP) males at the apex. In America, as early as 1630, the Puritan founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony had already declared themselves to be “a chosen people.” That self-identification of superiority initiated an ongoing westward expansion and expropriation of native lands based on racial and religious arrogance.3 The imperial ventures of the United States began shortly after its birth as a nation in 1776. In 1803 President Thomas Jefferson more than doubled the national territory with the Louisiana Purchase. Thereafter, trappers, traders, and hunters invaded the territory, seeking furs for commercial purposes in an early capitalist economy. The migratory Native American tribes who inhabited the vast area had hunted for sustenance, following immense herds of bison across the Midwestern plains. The incursion of Anglos signaled wholesale changes for the land and its inhabitants. White hunters perceived bison hunting not only as an economic activity but also as a sport, and by the end of the century they had decimated the herds and destroyed the Plains Indians’ nomadic culture. Even before the culmination of that conquest, American WASPs embarked upon international ventures.4 Missionaries from the United States arrived in Hawai‘i in 1820, preaching a conservative Protestantism and Yankee capitalism. Communal sharing of food, wives, and children perplexed the Anglos, one of whom stated that “the ease with which the Hawaiians . . . can secure their own food has undoubtedly interfered with their social and industrial advancement. . . . [It] relieves the native from any struggle and unfits him for competition with men from other lands.”5 The missionaries consequently banned gambling and Hawaiian sport forms such as surfing, boxing, and canoe racing as well as erotic hula dances. They introduced residential boarding schools in which conscripted children were indoctrinated with WASP culture, including the game of baseball. Later in the century the U.S. government adopted the boarding-school approach to acculturate Native American youth. By the 1840s missionaries to Hawai‘i enjoyed great influence as advisors to the monarchy, instituting judicial, commercial, and capitalist systems unfamiliar to the native population. Despite indigenous protests, the Great Mahele of 1848 began the division of land into lots for private ownership. By 1890 foreigners owned 75 percent of the islands’ acreage, much of it in plantations where baseball served as a social-control mechanism for a multiethnic labor force.6 The United States further expanded its boundaries by conquest in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848, and by the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867. The U.S. Congress rebuffed President Ulysses Grant’s attempted annexation of the Dominican Republic in 1870 but could not stop the cultural flow of baseball. Cuban boys, sent to school in the U.S., returned with bats and balls in the 1860s, and Cubans soon developed a passion for the game. They introduced it to the Dominicans and the Puerto Ricans in the 1890s. 4 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM American expatriates brought baseball to China as early as 1863, and teachers, military personnel, missionaries, and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), a proselytizing Protestant organization, promoted modern Western games throughout the region thereafter. With the formal abolition of the samurai class in Japan in 1876, sports proved a practical alternative to the samurai code of discipline, self-sacrifice, and deference to authority. In 1896 the elite Ichiko prep school finally achieved a long sought game with the Anglo Yokohama Athletic Club, which had banned the Japanese from its grounds. A stunning 29-4 Ichiko victory, accompanied by banzai chants and the singing of the Japanese national anthem, shamed the whites and engendered a long series of rematches. The Ichiko Baseball Club Annual Report of 1896 expressed the pain and redemption in the political, cultural, and athletic confrontation: The Americans are proud of baseball as their national game just as we have been proud of judo and kendo. Now, however, in a place far removed from their native land, they have fought against a “little people” whom they ridicule as childish, only to find themselves swept away like falling leaves. No words can describe their disgraceful conduct. The aggressive character of our national spirit is a well-established fact, demonstrated first in the Sino-Japanese War and now by our great victories in baseball.7 Buoyed with confidence after a series of victories over the expatriate and visiting American teams, the Japanese ventured on a ludic invasion of the United States. Intercollegiate contests between Japanese and U.S. schools commenced in 1905 as Waseda University sent its team to barnstorm Hawai‘i and the West Coast of the United States. The University of Washington sent its team to Japan in 1908, and the University of Wisconsin followed a year later. Such excursions were inevitably characterized as “invasions,” and Japanese collegians played accordingly, handily defeating the American contingents.8 In 1910 The University of Chicago stipulated particular conditions and took extensive precautions to ensure better results. Coach Amos Alonzo Stagg felt that the Washington and Wisconsin players had compromised both their performance and their morality by consorting with geisha girls, and he informed the Japanese hosts that his team would be unable to accept such “hospitality” due to their strict training. An accompanying faculty member assured the players’ compliance. Stagg also refused to play the best Japanese teams on successive days, and he received extensive scouting reports from Americans living in Japan, some of whom coached Japanese teams. Correspondence referred to both sides as “warriors” for the fall “invasion.” There was even a reference to meeting one’s “Waterloo.” Stagg’s team practiced with Chicago professionals, while Waseda prepped in the Oahu Baseball League in Hawai‘i throughout the summer. Stagg’s diligence paid off as Chicago, playing before huge crowds, swept the Japanese in ten straight games and then proclaimed itself “champions of the Orient.”9 By that time the United States had perceived Japan as a political threat in the Pacific. Japan had already defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, prompting General Leonard Wood to assert that “Japan is going ahead in a perfectly methodical philosophical way to dominate the Far East and as much of the Pacific and its trade as we and the rest of the world will permit. When she has a good excuse she will absorb the Philippines unless we are strong enough to prevent it.”10 Thereafter surrogate athletic wars Spring 2006 5 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY in baseball, the Far East Games, and the Olympics fueled Japanese nationalism and substituted for actual combat until the outbreak of World War II. In 1893 historian Frederick Jackson Turner proclaimed the frontier experience as the formative influence on the American character. With the economic collapse of that year, commercial interests looked for new frontiers, and Americans deemed themselves ready to assume international leadership. An Anglo coup, aided by U.S. troops, overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy, and Anglo fears of a growing Japanese presence in the islands led to annexation by the U. S. in 1898. Following the brief Spanish-American War that year, the United States found itself with a global empire as the resultant peace treaty awarded Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the entire Philippines archipelago to the victors. Colonialism initially engendered much debate in American society, with anti-imperialists, such as philosopher William James, charging that the United States was forsaking its democratic and egalitarian principles. The McKinley administration, however, sided with Congressman Albert Beveridge of Indiana, who stated: We will not repudiate our duty in the Orient. We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustees under God, of the civilization of the world. And we will move forward to our work, not howling out regrets like slaves whipped to their burdens, but with gratitude for a task worthy of our strength, and thanksgiving to Almighty God that He has marked us as His chosen people, henceforth to lead in the regeneration of the world.11 Protestant missionary groups rushed to the new lands despite the fact that the new territories were already Christianized by Catholics. The Protestants, however, considered their faith a purer form of Christianity, a higher stage of civilization.12 While religious leaders sought to save souls, and businessmen craved international markets, the military sought naval bases for their strategic value. The Philippines, Hawai‘i, and the Caribbean outposts provided refueling stations that would allow the U.S. to challenge Great Britain and Germany for dominance on the seas in an era when Theodore Roosevelt and many others believed that naval power was the key to global hegemony. Under Spanish rule in the Philippines and in the newly-acquired Caribbean islands, mixed races had proliferated. A more virulent strain of racism emerged under the Americans, who adopted many of the long established colonial practices of the British. WASPs denigrated subordinate groups in myriad forms of popular culture, such as newspapers, magazines, photography, art, and film in order to portray their superiority to themselves and their subjugated peoples. The primary means of indoctrination, however, proved to be education. Like the British, Americans attempted to impose the English language on the colonized peoples. With a dearth of English speakers in the subject lands, however, physical education and sports became an alternative means of infusing the characteristics necessary for competition in the modern industrialized world. Sports also measured the inferiority of non-white bodies, rationalizing the superiority of the dominant group. Throughout the colonies comprehensive athletic programs in schools, parks, playgrounds, and settlement houses, often run in close alliance with the Young Men’s Christian Association, attempted, with varying degrees of success, to inculcate a particular racial and religious ideology of whiteness. Cuba endured a relatively brief occupation in which Protestant missionaries carved up the island in jurisdictional tracts, attempting to convert the already thoroughly Chris6 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM tian country. In Protestant eyes, Cuban Catholics seemed little better than heathens. The missionaries found little success, but the YMCA persisted for decades in its attempt to mold proper moral character through sports and thus to avert the popular notion of Cuba as an exotic playground for men seeking sexual adventures. Sports held great economic and social promise, particularly for the downtrodden. A U.S. professional team, the Philadelphia Athletics, traveled to Cuba for competition with the natives in 1886, followed four years later by the New York Giants and a succession of barnstorming teams. Professional baseball fueled the aspirations of many who lacked the wealth and socioeconomic status to gain an education, a learned profession, and consequent respect. Professional athletes earned their salaries through physical prowess, independent of class affiliation or access to higher education. Widespread gambling on ball games created a need for highly skilled athletes, regardless of class or color. Cuba offered such opportunities on its professional and company teams, and civic rivalries fostered competition for the best players. El Base-Ball, a Cuban publication, stated that “one can hardly find any Cuban town that does not already claim as its own a club, perfectly uniformed and prepared to play.”14 The American declaration of war, occasioned by the explosion of an American warship in Havana harbor, had promised an independent Cuba. The new Cuban constitution, however, required approval by the United States. The establishment of a U.S. protectorate over the island guaranteed the Americans a now notorious naval base at Guantanamo Bay and undue influence over the Cuban government, economy, and military. The handpicked first president, Tomas Estrada Palma, spoke English, converted to the Quaker faith, and held U.S. citizenship. Secretary of War Elihu Root congratulated Governor-General Leonard Wood for the “establishment of popular self-government, based on a limited suffrage, excluding so great a proportion of the elements which have brought ruin to Haiti and San Domingo.” The elements to whom Root referred were black Cubans, many of whom composed the Cuban liberation army that fought against the Spanish. By 1905 an American visitor observed that “Negroes . . . are deprived of positions, ostracized and made political outcasts. The Negro has done much for Cuba. Cuba has done nothing for the Negro.”15 The early promise of baseball was similarly negated by American racial attitudes when American professional teams refused to hire any but light-skinned Cuban players. American control of the educational system doomed blacks to an unequal role in Cuban society. Protestant sects, aided by corporate sponsors, founded more than one hundred schools that advocated vocational training and WASP morality. James Wilson, the governor of the Matangas province, ordered English books for his charges because “unquestionably our literature will promote their knowledge, improve their morals and give this people a new and better trend of thought.”16 Such ethnocentric views permeated relationships between the colonizers and the colonized. After a brief period during which Cubans were relatively free, Americans resumed their occupation of the island in 1906. Cuban resentment led to open hostilities and a surge in nationalism over the next three years. In the meantime, athletes engaged in surrogate wars as Cubans and Americans met in baseball, football, basketball, and track-andfield competition. Cubans, however, refused to adhere to Protestant admonitions about Sunday play, and the Catholic Church vigorously opposed YMCA operations. Major league Spring 2006 7 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY teams continued to travel to Cuba, however, and baseball continued to foster a nationalistic spirit. Cuban teams won seven of eleven contests against the Cincinnati Reds in 1908, the same year that Cuban voters ousted the carefully selected Tomas Estrada from the presidency. Cubans split eight games with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1909 but took eight of twelve from the Detroit Tigers, defending champions of the American League. In 1910 a Havana team defeated Tulane University of New Orleans in a football game. By 1911 American League President Ban Johnson forbade travel to Cuba, where such losses at the hands of racially mixed teams upset prevailing perceptions of white superiority. Similarly, authorities banned boxing in 1912, as such direct confrontations threatened to upset the hegemonic order.17 By 1918 U.S. domination of the Cuban economy accounted for 76 percent of Cuba’s imports and 72 percent of its exports. American control of the economy and the consequent loss of land by poor peasants to wealthy interlopers precipitated a civil war along racial and class lines in 1912, resulting in more than 6,000 Cuban deaths. In Havana Americans transformed the culture by their recreational practices and their imposition of the English language. The city became a playground for wealthy or adventurous foreigners. In the countryside American corporations, which owned more than a third of the sugar mills, established recreation programs aimed to serve as social control. More than a hundred mills fielded baseball teams. Many baseball players, however, refused to accept the lessons of docility. Baldomaro Acosta, formerly a pitcher for the Washington Senators, returned to his homeland to lead a native revolt in 1917 before support from the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps arrived to support the conservative government and protect American businesses.19 While the U.S dominated the economy, Cubans managed to retain their pride and respect on the baseball field. Despite political upheaval, the Cuban national team won the Central American Games title in 1935. The following year, Cuba’s political factions united for a series against the St. Louis Cardinals. By 1939 Cubans had won the World Amateur Championship, a feat they repeated from 1942 to 1944. Such successes continued over the next two decades. After Fidel Castro’s successful Communist revolution, sports became an explicit political weapon. Cuban Olympians excelled in track and boxing, while its baseball teams repeatedly beat the Americans at their own game.20 Puerto Rico fared less well, as race and religion figured prominently in American mandates. Soon after the Spanish-American War, American administrators banned gambling, dueling, and cockfighting on the island and imposed the English language in the schools. WASP anthropologists from the mainland traveled to Puerto Rico to study the natives, whose Spanish past they extolled, while denigrating their African heritage. After a three-year study, anthropologist Jesse Fewkes determined Puerto Ricans to be “primitive, illiterate, idolatrous, destitute, superstitious, and dark-skinned.”21 The Americans decided that such barbarous and immoral characteristics had to be eliminated and new ways learned. Schools added moral training to their curriculum and teachers were required to be familiar with “American” methodology, which was taught in a newly established teacher-training institute.22 Suffrage was granted only to literate adult males who voted for a non-voting representative in the U.S. Congress. The U.S. president appointed the governor and the executive council, and the U.S. Supreme Court adjudicated all final appeals. Whereas 93 percent of 8 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM all farmers had owned their own land in 1898, new land taxes soon evicted them. They were replaced by wealthy investors and large corporations, most of them American.23 The entry of Americans brought a more varied and comprehensive sporting culture to Puerto Rico. As in Cuba, baseball had preceded the arrival of Americans. Cubans had exported the game to Puerto Rico, and by 1896 the Almendares and Borinquen clubs battled each other in San Juan. Within four years, company and school teams engaged in tournament competition, but one of the first postwar American requests to the newly installed Adjutant General included “a modern athletic club for recreation with billiard rooms, bowling alleys, a library, outdoor field sports, running and wheel (cycling) tracks, ball grounds and beer sales to allow for proper recreation.”24 The YMCA soon inserted itself and began using sports to facilitate its proselytizing efforts. The “Y” introduced basketball, volleyball, fencing, tennis, handball, and track and field meets with medals, trophies, banners, ribbons, and pennants to attract participants. A 1916 report stated that “through this Athletic Meet we gained access to many young men who had not been in touch with the Association.”25 The YMCA found temporary success in organizing women’s basketball teams until men commandeered the gym space. Both gender and racial divisions hindered Protestant efforts. The director of the San Juan YMCA revealed that he had to turn away an applicant who was “too dark” and of Negro blood, though “the young man seemed to be a gentleman.” Blacks had contributed money to the construction costs of the building under the assumption that all were welcome; the YMCA, nonetheless, returned their membership applications. The YMCA also failed to connect with Puerto Rican baseball players because the “Y” refused to play on Sundays, the primary day for island competitions.26 Despite race, class, gender, religious, linguistic, and cultural differences, Americans continued their attempts to assimilate the indigenous peoples. The U.S government granted citizenship to Puerto Ricans in 1917, though nationalist leaders on the island opposed the move. Despite mandatory English lessons in the schools, few outside the urban areas mastered the foreign tongue. By 1920 only one-third of Puerto Rican children even attended school. Despite government bans, cockfighting continued throughout the island. Indigenous residents saw little value in adopting the materialistic ambitions of capitalism when plantation workers earned no more than four dollars a day for ten to twelve hours of labor. Women received only half as much. By 1930 U.S. corporations owned 60 percent of the sugar industry, 60 percent of the banks and public utilities, and 80 percent of the tobacco business. Puerto Rico still has commonwealth status but remains a poor stepchild within American polity.27 Race and racism permeated the American colonial experience. By 1911 the Dillingham Commission on Immigration into the United States concluded that there were forty-five separate races. Professor Daniel Brinton, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, declared that “the black, brown, and red races differ anatomically so much from the white . . . that even with equal cerebral capacity they never could rival its results by equal efforts.”28 General Leonard Wood, colonial warrior, governor, and presidential candidate, also asserted that “[n]o one . . . can question the inadvisability of the introduction of any other alien race, of a black, brown, or yellow strain into this country. We must make it a white nation.”29 While such racist beliefs had great support within the United States, the Philippine Islands posed problems for assimilation. Spring 2006 9 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY The Philippines endured nearly a half century of U.S. governance, in what one historian has termed a “laboratory for social reform.”30 Reforms introduced by the United States attempted wholesale changes in government, administration, education, cultural beliefs and practices, and recreational forms. Characterizing the natives as heathen savages, to the surprise of many Catholics, American Protestant missionaries and school teachers rushed to assume the white man’s burden. Dean Worcester, a zoologist at the University of Michigan, had traveled to the islands for specimens in 1887 and during the early 1890s. With the eruption of the Spanish-American War, he assumed the mantle of an anthropological expert, stereotyping all Filipinos with his descriptions of headhunters and primitive tribes. The U.S. government appointed him to the Philippines Commission, and he served as Secretary of the Interior until 1913. Worcester recommended baseball as a means “to strengthen muscles and wits.”31 The baseball campaign had already been long underway, introduced by the American soldiers shortly after their arrival in 1898. General Franklin Bell, commander of U.S. forces in Manila, stated that “baseball had done more to ‘civilize’ Filipinos than anything else.”32 The American-owned Manila Times declared that baseball “is more than a game, a regenerating influence, a power for good.”33 After their arrival in 1901, American teachers continued the practice of schooling Filipino children in baseball. Like other colonizers, Americans tried to recreate their homeland in the Philippines. Protestant missionaries dispensed the King James Bible and tried to convert the natives to their version of Christianity. Officials banned gambling, cockfighting, and lotteries in conformity with Protestant standards of morality. School officials introduced public education models from the states that emphasized vocational training and imposed English instruction with the intention of replacing the multitude of tribal languages. Famed architect Daniel Burnham arrived to reconstruct Manila and to design a summer capital in the more salubrious mountains. Burnham claimed that “Americans . . . are used to better conditions of living. . . . [T]he two capitals of the Philippines, even in their physical characteristics, will represent the power and dignity of this [U.S.] nation.”34 Streets assumed American names, the grand boulevard that skirted the bay honored the American war hero Admiral George Dewey, and Americans claimed the best land for their military and commercial interests. Filipinos learned to celebrate American holidays and to play American games.35 The YMCA established itself with close ties to the government and the public schools system. YMCA workers prepared official recreation manuals, trained playground staff, and even assumed the role of acting director of public education. Combining their efforts with those of Episcopalian Bishop Charles H. Brent, who also served as president of the Philippines Amateur Athletic Federation, Protestants assumed undue power and influence in a nation composed mostly of Catholics and Muslims.36 The YMCA reached its apex under the governorship of W. Cameron Forbes, a Boston Brahmin, grandson of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and former Harvard football coach, who fully subscribed to the progressive powers of sports. Appointed to the Philippines Commission in 1904, Forbes assumed the governor-general’s position from 1909 to 1913. Formal interscholastic competition and required physical education classes for both boys and girls had already begun in 1905. A series of baseball games with Waseda University of 10 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM Japan also enabled Americans to channel a growing Filipino nationalism into athletic rivalry. The Manila Carnival, organized in 1908, reinforced the nationalistic spirit by spurring town and regional rivalries into an athletic spectacle of national championships. Forbes awarded complete uniforms, trophies, and prizes to top teams. By 1913 more than 1,500 baseball teams competed for the awards and 95 percent of the schools’ enrollment participated in sports and games. Physical education accounted for more class time than all other subjects except reading. The Bureau of Education stressed competitive athletics so much that by 1916 its formal policy allowed students to supplement their grade-point averages and make up deficiencies by participating in provincial athletic contests. Those who competed in the national championships at the Manila Carnival gained even more benefits.37 The comprehensive athletic plan, which included the playgrounds, settlement houses, and the YMCA, surpassed the efforts of contemporary progressive reformers in the United States. Under the directorship of Elwood Brown, the YMCA transformed the Manila Carnival from a commercial exhibition to an athletic spectacle. The carnival achieved recognition as the Far East Olympics with the inclusion of teams from Japan and China in 1913. Participation in this event, which became the quadrennial Far Eastern Games, fostered a greater Filipino nationalism. Despite the YMCA’s intentions of regional integration through sport, it practiced a policy of racial segregation in Manila. It allowed for open competition between the races but maintained separate buildings for whites, Filipinos, and Chinese. Interracial competition, however, did allow Filipinos to challenge white notions of Social Darwinist superiority. After Filipino clerks defeated their American bosses in the 1915 Philippine Amateur Athletic Federation volleyball tournament, WASPs promptly changed the rules to eliminate the natives’ “deceptive” strategy.38 In addition to the volleyball victory, Filipino baseball teams defeated both the Japanese and their American tutors on occasion. Boxing, too, offered opportunities for racial comparison and retaliation for American slights. Introduced by American soldiers in 1898, boxing soon became a favorite of the Filipinos. By the 1920s Filipinos reveled in their own champions, including world flyweight title-holder Pancho Villa. American sportswriters racialized Villa’s abilities, characterizing him as a simian demon who moved too quickly for normal fighters. Like the African-American heavyweight champion, Jack Johnson, Villa offended white racial attitudes by consorting with white women during a two-year sojourn to the United States. Similarly, his flamboyant lifestyle stood in stark contrast to the abstemious WASP standards of middle-class aspirants. Yet, when he died of blood poisoning in 1925, Filipinos considered it a national tragedy. Manila streets were draped in black as 100,000 attended his funeral.39 Numerous other Filipino boxers challenged the notions of white physical superiority. Welterweight Ceferino Garcia, inspired by Villa, later developed the “bolo punch,” symbolic of his Filipino identity. Garcia attracted a large following among Filipino laborers in the United States as he pummeled his way to the championship. In such a context the racially superior attitudes espoused by whites were demonstrably invalid.40 Still, Americans claimed success and took credit for the improved health and physical performances of their colonial charges. As early as 1911 the director of education claimed Spring 2006 11 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY that the baseball diamond had replaced the cockpit and that the “new spirit of athletic interest . . . is actually revolutionary, and with it came new standards, new ideals of character.”41 Six years later the health service claimed that sports had decreased the cases of tuberculosis. The Philippine Constabulary thought its recruits had increased their physical stature over those of the previous decade, “due no doubt to athletic training . . . in the . . . schools of the Islands.”42 Students who failed physical education were not promoted to the next grade because the Bureau of Education maintained that exercise was necessary to make Filipinos larger and “that the stock of the race can be improved considerably.”43 Despite the grandiose assertions, the American crusade elicited mixed results. Geographical features, such as jungles, mountain ranges, and the more than 7,000 islands that compose the archipelago and its polyglot population, thwarted American efforts for full enculturation. The Americans’ appointment of elite, educated Filipinos to governmental posts actually entrenched the Spanish caste system and did little to bring true democracy to the populace. Filipino nationalism increased as the U.S. government continually delayed an independence date, and American control of the economy eventually produced a reactionary Communist movement. The YMCA retained a measure of influence for decades but gained few converts to Protestantism. Catholic priests threatened YMCA members with excommunication. By 1934 even the Far East Games, organized by the “Y,” dissolved in discord. The YMCA’s most lasting imprint proved to be the adoption of basketball as the Filipinos’ national game.44 Hawai‘i endured a longer colonial administration before eventually becoming a state. The missionaries’ overriding influence in Hawai‘i enabled them to introduce baseball as a popular sport. By the 1870s Honolulu had a four-team league and thousands of enthusiastic spectators. Polo, tennis, and track and field competition ensued in the following decade, but the transition in sporting culture was neither complete nor uncontested. Natives resurrected canoe racing in 1875 and the previously banned hula dancers entertained King Kalakaua at his fiftieth birthday jubilee in 1886. The nationalistic king opposed the cession of Pearl Harbor to the U.S., and he revived the native language and music. Indigenous Hawaiians supported their sovereign in politicized chants and lyrics. Sensing the loss of their privileges and established hegemony, the all-white Hawaiian League imposed the so-called Bayonet Constitution on the king in 1887, stripping him of his power. In spite of this action, the anti-American National Reform Party won all seats in the Oahu elections of 1890. The king died the next year, but his successor, Queen Liliuokalani, proved as strident in her nationalism. Her intransigence resulted in an 1893 coup led by American businessmen and supported by a U.S. diplomat and a contingent of marines. The “provisional” government and its new constitution disfranchised 14,000 voters, while limiting suffrage to only 2,800, most of them employees of the American-owned Dole Company. Not surprisingly, Sanford Dole, son of missionaries and himself a wealthy plantation owner, assumed the presidency.45 Fearing a Japanese takeover, the Honolulu Star enflamed racial animosities by proclaiming, “It is the white race against the yellow. . . . Nothing but annexation can save the islands.”46 Despite protests from native Hawaiians, the U.S. government complied with the request for annexation, adding the islands as a territorial possession in 1898. A white, commercial oligarchy controlled almost all trade but not culture; sports became contested terrain. Although baseball had served plantation owners as a social-control device, the 12 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM game could not quell discontent. Workers began attacking overseers and managers and committed acts of arson. Insubordination, work slowdowns, and a rash of strikes limited production and profits. Traditional sports such as Japanese sumo and Filipino sipe became popular in the multicultural labor force.47 In urban areas, engagement in Anglo sports offered opportunities for retaliation. In 1903 the girls of the Kamehameha School, reserved for Hawaiians, defeated the YMCA team in basketball, a game the “Y” had invented. In the wake of Chinese exclusionary practices on the American mainland, a Chinese-Hawaiian baseball team began a tour of the U.S. in 1910, winning the majority of its games. By 1913 they had won fifty-four of the fifty-nine games played against American college teams, and in 1914 they allegedly defeated the New York Giants.48 Sporting practices also served to stem and even reverse the cultural flow. Surfing and canoe racing, banned by the missionaries due to associated gambling and scanty attire, continued clandestinely. By the turn of the century, white boys had become attracted to these Hawaiian pastimes. By 1908 businessmen formed the Outrigger Canoe Club in the hope of spawning commercial opportunities at Waikiki Beach. Surfing clubs enjoyed similar aquatic facilities at the beach by 1911, and George Freeth, the product of a mixed marriage, introduced mainlanders to surfing and water polo when he traveled to California.49 Duke Kahanamoku promoted surfing in Australia in 1916, but he gained greater fame as an Olympic swimmer, garnering six medals for the United States from 19121932. Hawaiian swimmers on both male and female swimming teams represented the United States on the international stage, winning a measure of respect and acceptance from the dominant culture. Kahanamoku married a white woman and parlayed his fame into a movie career and political office, but his adherence to Hawaiian foods, language, and issues demonstrated a merger of cultures.50 The location of the Hawaiian Islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean made them a cultural crossroads. The diversity of Hawaiian society and its sporting relationships offered experiments in racial integration long before most mainland communities. Close ties between Japanese residents of the islands and their homeland brought Waseda University’s baseball team to Oahu in 1905. In 1910 it played in the Oahu summer league. The Honolulu League featured Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Portuguese athletes, but Chinese and Japanese players also played the American game in ethnically-based separate associations. Industrial teams also fielded ethnically mixed squads, so by 1919 baseball offered some hope of conciliation. A plantation manager explained: Every Sunday we have baseball games between the Filipino laborers and our young Japanese and Portuguese boys in which our timekeepers and some of our overseers join. . . . In looking around at the universal unrest amongst labor and thinking of the absence of it upon these Islands, we feel an unremitting endeavor should be made to keep our laborers contented and happy.51 Furthermore, the U.S. Army’s assignment of the African-American Twenty-Fifth Regiment to Hawai‘i in 1913 afforded additional opportunities for racial interaction. The soldiers proceeded to win the islands’ baseball and track championships.52 Hawaiians adapted Anglo sports to their own conditions. Volleyball, played on the beach, eschewed six-man teams in favor of two or four competitors to better test speed, agility, and stamina. Barefoot football, also played on the beach, emphasized speed and Spring 2006 13 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY rugged play, working-class attributes considered more masculine than “white” styles of play. Japanese, Chinese, Portuguese, and native Hawaiian teams abounded in workingclass neighborhoods by the 1920s. The University of Hawai‘i’s 1938 team reflected the heterogeneity of the local culture with fifteen different ethnicities represented on its twentyfour-man traveling roster.53 World War II interrupted the cultural negotiation transpiring in Hawai‘i, bringing large numbers of mainland military personnel to a multitude of combat bases and forever changing the geographic, social, and cultural landscapes of the islands. Tourism further increased after the war, which intensified the trend toward commercialism. The Korean and Vietnam Wars brought new martial legions to the island shores, many of whom returned as tourists. The tourist boom fueled the construction of so many high-rise hotels, shopping malls, and golf courses that Hawai‘i lost much of its uniqueness and exoticism. Culture, however, remained a battleground as elements of the polyglot population of Hawai‘i, including middle-class whites, reacted to developers’ intrusions in the 1970s. Some natives-rights groups sought complete independence, others wanted separate-nation status, and still others demanded reparations. Native politicians, led by JapaneseHawaiian Democrats, succeeded in overthrowing the Republican Party, which had dominated public affairs from annexation until World War II. Although tourism accounted for a third of jobs in Hawai‘i, demonstrators railed against the commodification of culture and the loss of native traditions. They pointed angrily to the fact that many of the more than one hundred albums of Hawaiian music released in 1978 characterized the natives as “lazy but happy.”54 Disparate groups successfully consolidated in a movement known as the Native Hawaiian Renaissance. Four of the major companies that had prevailed over the Hawaiian economy during the past century were dismantled or sold. Lobbying efforts and boycotts A basketball court stands as an aftermath of U.S. acculturation in Hawai‘i. COURTESY OF 14 GERALD R. GEMS. Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM of the public schools led to the reinstatement of the Hawaiian language, banned since 1896. The island of Kahoolawe, used as a military bombing site, reverted to the Hawaiian people in 1994 after a successful lawsuit. Schoolchildren began paddling their canoes to the island for lessons about their ancestral culture. Legislation banned commercial trawlers from traditional fishing waters, and native swimming and surfing spots were designated as state beaches to thwart hotel developers. In 1993 President Clinton finally offered a formal apology for the 1893 coup.55 The renaissance produced a resurgence in traditional sports as well. Many clubs, formed to compete in outrigger canoe racing and surfing, enjoyed international popularity. American sporting forms had been imposed on Hawaiians as a form of social control, as a “civilizing” influence, and as a means to impart a particular ideology. Hawaiians resisted, adapted, and adopted them in recurring cycles for nearly two hundred years. During that time, the cultural crossroads of Hawai‘i received migrants from a multitude of countries. That racial and ethnic mix eventually resulted in integration and cooperation, especially noticeable in sporting ventures, long before statehood and the contested legalization of civil rights in the continental United States. Cultural imperialism, however, proved to be less than a unilateral process in Hawai‘i, as surfing migrated to the American mainland and other international destinations. Hawaiians traveled to Japan to pursue professional athletic careers as baseball stars and sumo wrestlers. Native Hawaiian sports survived or were revived despite WASP attempts to extirpate them. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the United States also engaged in imperial adventures throughout the Caribbean, though they were not of a permanent nature. Interest in a Caribbean naval station to safeguard a proposed canal across the Central American isthmus brought U.S. forces to various islands. The American military seized control of Dominican customs in 1905 to pay off debts owed to American firms. They returned in 1911 to protect American interests and to supervise an election after the assassination of the Dominican president. American marines eventually established a military government that held power until 1924. As in Hawai‘i, baseball proved a splendid means of social control. As early as 1913 James Sullivan, the U.S. minister to the Dominican Republic, wrote to Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan: I deem it worthy of the Department’s notice that the American game of baseball is being played and supported here with great enthusiasm. The remarkable effect of this outlet for the animal spirits of the young men, is that they are leaving the plazas where they were in the habit of congregating and talking revolution and are resorting to the ball fields where they become wildly partizen [sic] each for his favorite team. The importance of this new interest . . . should not be minimized. It satisfies a craving in the nature of the people for exciting conflict, and is a real substitute for the contest in the hill-sides with rifles, if it could be fostered and made important by a league of teams . . . it well might be one factor in the salvation of the nation.56 Sullivan’s words proved prophetic, but not in the manner in which he envisioned. Thereafter, armed struggles between the Dominicans and American marines were matched by confrontations in the ballparks, as baseball bolstered Dominican pride. Unlike the American emphasis on power, Dominicans emphasized their own style of play. The natives favored flair, grace, speed, and hustle in what became known as beisbol romantico.57 Spring 2006 15 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY A boys’ baseball game in Nicaragua. COURTESY OF GERALD R. GEMS. Baseball provided pride when the Dominicans defeated the Americans or Cubans, their Caribbean rivals. Local professional leagues provided opportunities and hope for those stuck in the dreary existence of work on sugarcane plantations. By the 1950s Dominican players began appearing on American major league rosters, and by the end of the twentieth century, baseball players became a major export for the country. At the beginning of the 2000 baseball season, Dominicans comprised 10 percent of all Major League Baseball players. They had learned to evaluate their own worth, requesting and receiving astronomical sums for their baseball talents. Unlike Cubans, who used baseball as a political and retaliatory weapon, or Puerto Ricans, who suffered an identity crisis along with exploitation through their long association with the United States, Dominicans learned well the lessons of capitalism. They managed to retain their local culture, benefit from their human resources, and generate national pride through sports.58 Americans had shown an early interest in Nicaragua as well. William Walker, a freebooter, invaded the country during the mid nineteenth century in a failed attempt to establish a slave republic. Walker’s debacle did not deter American interest in building a canal across the country or commercial interests from following the United Fruit Company to Nicaragua soon after its founding in 1889. Such business and political concerns brought American troops to the country in 1911-1912, 19261932, and for clandestine CIA-sponsored operations during the 1980s. Baseball arrived with the banana companies, and Managua sported a league by 1911. American intrusion in local political affairs and the American military presence over the next two decades engendered animosity. Baseball and boxing provided some of the more viable means for retaliation. In one such encounter, a local sportswriter touched upon the political and racial connotations of the competition. With the Titan team from Nicaragua losing a baseball game to a U.S. Navy team, 15-9 in the last inning, he wrote: 16 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM The huge crowd is sad; not a happy voice is heard. Titan seems defeated; but the nine Nicaraguan boys, as if in a war between races, exalted by their Nicaraguan pride, as though influenced by powerful Indian blood, entered the bottom of the ninth with an enthusiasm spurred on by the screams of the crowd. Titan responded with a 16-15 victory that thrilled the partisan crowd.59 The confrontations were even more personal in boxing matches, which in the 1920s preceded the baseball games as commercialized spectacles. Athletic triumphs fostered nationalism, and Nicaraguans soon sought regional competition. In 1923 Nicaragua entered the Central American Games at San Salvador. A year later, Nicaragua defeated Panama for the regional baseball championship. Nicaraguan boxers carried the national mantle against their Guatemalan and El Salvadorean counterparts as such ventures helped to build nationalist sentiments.60 Nicaraguan dictator Antonio Somoza recognized the power of sport. After assuming dictatorial powers in 1936, he built a baseball stadium in Managua. The Somoza family enjoyed American support until the revolutionary Sandinista party overthrew his son in 1979. The Sandinistas sponsored a team in the national baseball league, winning the championship in 1988. When Dennis Martinez, a Nicaraguan and star pitcher for a number of American major league teams, retired in 1998, the citizens of Nicaragua renamed the stadium after him. Martinez declined to run for the presidency, but the movement to draft him for such a role indicated the importance of baseball to this poverty stricken nation.61 The Estadio Dennis Martinez in Managua is named after the Nicaraguan major league star pitcher. COURTESY OF GERALD R. GEMS. Spring 2006 17 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY Panama, too, felt the weight of American power. In fact, it owed its existence to the United States, which orchestrated its secession from Colombia in 1903. Backed by the American military, Panamanian politicians declared their independence and quickly awarded the U.S. with the rights to build and hold the Panama Canal. The United States employed a multinational labor force to build the canal with the usual lack of rights and privileges accorded to non-whites. In time the YMCA supplied a host of recreational facilities for white residents in the Canal Zone. A baseball league was formed by 1912. Sports provided one of the few outlets for Panamanian nationalism as the United States dominated affairs for most of the century.62 “Panama Al” Brown stood over 5’10” and had a 76-inch reach as a flyweight boxer. Whites characterized him as a “freak,” yet Brown held the bantamweight title from 1929 to 1935 in a career that spanned twenty-two years. Brown’s tenure coincided with the formation of a specifically Panamanian identity and the questioning of U.S. sovereignty in the Canal Zone. One product of nascent Panamanian nationalism was a new treaty signed in 1939 that limited the role of the United States. As political squabbles continued throughout the latter half of the century, Panamanians found a new hero in boxer Roberto Duran.63 A street urchin who began fighting professionally in 1967 at the age of sixteen, Duran fought with a ferocious intensity and a toughness that overwhelmed his opponents. Capturing four world titles, he became a national icon, sharing his winnings with poor supplicants. “I understand the importance my life holds for people who are poor and have nothing,” he declared.64 Even as American troops invaded the country to overthrow the dictator, Manuel Noriega, Panamanians took comfort in their athletic stars. Duran kept fighting until a car crash at age fifty forced his retirement. By that time, more than two dozen Panamanian baseball players had made it to the major leagues in the United States. Through such athletes, Panamanians saw images of themselves—poor, but tough, gritty, and proud, able to compete with the Americans on a level playing field.65 Haitians never got such opportunities. The United States made repeated incursions into the technically independent country throughout the twentieth century. In 1910 it took control of the Haitian national bank. Five years later the U.S. invaded and replaced the president with a puppet government, effectively transforming the country into a protectorate. Americans rationalized such incursions under the guise of the “white man’s burden.” The National Geographic magazine described this country as “a region where nature has lavished its richest gifts, and where a simple population, under a firm yet gentle, beneficent guidance, may realize the blessings of tranquil abundance.”66 A rebellion of black Haitian patriots, known as Cacos, erupted into a guerrilla war, resulting in an occupation that lasted until 1934. Americans tried to impose the English language, their own moral codes, and vocational training. Haitians likened the impressment of labor gangs as a return to slavery. Sports and other recreational practices remained largely segregated, as a virulent racism clearly played an important role in the lack of integrated pastimes. The Haitians proved to be too proud, too black, and too poor for assimilation, and the United States expressed little further interest between 1934 and the 1990s when the Clinton administration intervened forcefully in Haitian politics.67 Military rather than economic needs motivated the accumulation of Pacific outposts for the American empire. Soon after an American expedition arrived in Samoa in 1839, 18 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM Protestant missionaries followed. Their emphasis on individualism contrasted with the communal society of the Samoans. Americans initiated cultural changes. Beginning in the 1880s, the United States, Germany, and Great Britain competed for ascendency over the Samoan Islands and its people, resulting in the eventual division of the island group between Germany and the U.S. in 1899. The U.S Navy governed the residents until 1951, establishing schools that promoted the English language, moral education, and vocational training. Interracial marriages required governmental consent. Samoans did not gain universal suffrage until 1977, but little remained of their native culture by that time. Commercialization replaced traditional farming, English intruded upon the Samoan language, while American popular culture attracted youth. One new sporting form, American football, attracted the natives’ interests and allowed Samoan males to continue to display their masculinity through demonstrations of physical prowess.68 Samoans’ adoption of football enabled many young males to earn athletic scholarships to universities in the United States. Toniu Fonoti, one of five Samoans on the 2001 University of Nebraska team, claimed that Samoan physiques and cultural value were ideal for football. Many of his countrymen are large, powerful, and agile, and Samoans possess stoic toughness, discipline, and a competitive, aggressive nature well-suited to the game. 69 While sports provided some opportunity and brought disparate cultures closer together, they have also forged a greater sense of national identity as Samoans embarked on their own paths. In 1981 the Samoan basketball team competed in the first Ocean Tournament, a regional competition held in Fiji. Four years later Samoans established their own national Olympic committee, further enhancing their self-esteem and a separate cultural identity. In 2001 the territory conducted its first American Samoa Games, and its best basketball players joined regional all-stars from Fiji, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and the Solomon Islands for competition against Anglos in Australia. The regional alliance signaled a growing sense of difference even as the globalization of sports brought distinct cultural groups together in a common purpose.70 Guam underwent similar cultural transformations after it fell to the United States as a war prize after 1898. American administrators replaced Spanish with English and supplanted local festivals with American holidays. Village chiefs lost their power, and Catholic friars were expelled from the island. The new U.S. naval government enforced its own moral standards by banning cockfights, whistling, serenading, and religious processions. Naval officers spent time regulating the length of women’s dresses. As in Samoa, the American emphasis on individualism fragmented the local Chamorro communal culture, a process exacerbated by the navy’s segregationist policies. Natives had little recourse as the Insular Cases, adjudicated before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1900-1901, classified territories as different from states and, therefore, residents did not have the same constitutional rights as other Americans.71 Sports provided a less formal but clearly visible means of reclaiming lost honor. The navy initiated a sports program to serve as a prophylactic device against the suspected physical and moral degeneracy of the tropics. Much to the surprise and embarrassment of the naval personnel, the lone native team in the baseball league defeated the officers’ team for the championship. Labeled “the Great White Hopes,” the military brass supposedly represented the cream of American manhood.72 Spring 2006 19 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY American popular culture has spread well beyond the scope of this article as evidenced by the poster advertising an American football game between teams in Prague, Czech Republic, above, and the Pepsi ad found in a park in Lima, Peru, right. COURTESY OF GERALD R. GEMS. The introduction of Filipino workers and the Japanese occupation during World War II further disintegrated the local Chamorro culture. Then, the postwar influx of Japanese and American tourists brought greater commercialization, a loss of native lands, and a local backlash. A nationalist party emerged in the 1970s, pitting itself against the nonChamorro Filipinos, Japanese, and Chinese residents. Adherents defied the ban on their native language, eventually winning its acceptance in the island’s schools.73 Sports allowed for some alleviation of local tensions by generating multiethnic unions and pride in pluralistic triumphs. Team sports like baseball and football reinforced the traditional communal habitus of the diverse Asian populations. Coaches served as father figures in the team “family.” Football linked authority and discipline with the masculinity and physical performance important to adolescent boys. One team composed of Hawaiian players won 125 consecutive games over a fifteen-year span. In 1999 another Guam football team defeated one from Russia, a former world political power, in an international tournament in the United States. The athletic successes of polyglot teams from Guam restored the respect, dignity, and confidence of subordinate groups that had previously labored under white Anglo domination.74 Both administrators and practitioners found many uses for sports in the cultural interplay that transpired in colonialism. Sports served as a mechanism for social control, but they also provided an integrating force among disparate groups. In some cases sports allowed for a compensatory or retaliative response to oppression as subordinate or colonized peoples defeated the United States at its own games. Some of the colonized adapted sports forms to their own cultural values and developed their own distinctive styles of play. In all cases, race, religion, and time determined the extent of cultural transformation. Assimilation to American cultural values generally failed in occupations of less than two 20 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM generations. In almost all territories under its control, except in Hawai‘i, the United States proved unable to change religious values despite ardent efforts by Protestant missionaries and the YMCA. Americans provided an infrastructure of roads, schools, and civic services, but they could not instill democracy in Asia or the Caribbean, where dictators continued to reign for decades after the departure of American troops. American governance, too, often catered to American businesses rather than promoting indigenous commerce; capitalism did not automatically breed democracy. Sporting forms and practices offered myriad responses in the negotiation of culture, ranging from acculturation to political and surrogate warfare. The only certainty was that both dominant and subordinate groups would be changed in the process. 1 Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 8. See Frederick Upham Adams, Conquest of the Tropics (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1914) in the heroic genre as well as the more contemporary works of Stephen Ambrose. See Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), on historical constructs. 2 C.L.R. James, Beyond a Boundary (London: Sportmans Book Club, 1964; reprint ed., Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1993). Among the more critical works are Marc Ferro, Colonization: A Global History (London: Routledge, 1997); David B. Abernethy, The Dynamics of Global Dominance: European Overseas Empires, 1415-1980 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000); and John A. Guidry, Michael D. Kennedy, and Mayer N. Zald, Globalization and Social Movements: Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000). American treatments are offered by Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1987); Deborah Wei and Rachael Kamel, eds., Resistance in Paradise: Rethinking 100 Years of U.S. Involvement in the Caribbean and the Pacific (Philadelphia: American Friends Service Committee, 1998); Amy Kaplan and Donald Pease, eds., Cultures of United States Imperialism (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1993); and Jean Heffer, The United States and the Pacific: History of a Frontier (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2002). J.A. Mangan’s works include The Games Ethic and Imperialism: Aspects of the Diffusion of an Ideal (Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin Books, 1986; reprint ed., London: Frank Cass, 1998); The Imperial Curriculum: Racial Images and Education in the British Colonial Experience (London: Routledge, 1993); The Cultural Bond: Sport, Empire, Society (London: Frank Cass, 1992); and Making Imperial Mentalities Socialisation and British Imperialism (Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press, 1990). For the diffusion of sports globally, see Allen Guttmann, Games and Empires: Modern Sports and Cultural Imperialism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994). For somewhat more limited studies, see Joel S. Franks, Hawaiian Sports in the Twentieth Century (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press, 2002); idem, Crossing Sidelines, Crossing Cultures: Sport and Asian Pacific American Cultural Citizenship (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 2000); and Joseph A. Reaves, Taking in a Game: A History of Baseball in Asia (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002). Murray G. Phillips, “Deconstructing Sport History: The Postmodern Challenge,” Journal of Sport History 28 (2001): 327-343, provides a helpful critique. 3 Among the numerous works on whiteness, see David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991); Lee D. Baker, From Savage to Negro: Anthropology and the Construction of Race, 1869-1954 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998); Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981); Matthew Frye Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998); and Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981). 4 Pekka Hamalainnen, “The Rise and Fall of Plains Indians Horse Cultures,” Journal of American History 90 (2003): 833-862, indicates extermination of Eastern herds by 1825. Western herds provided some sustenance for another fifty years. Spring 2006 21 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY 5 Cited in “Expansion in the Pacific,” <http://www.smplanet.com/imperialism/hawaii/html> [24 September 1999]. 6 Michael Kioni Dudley and Keoni Kealoha Agard, “A History of Dispossessions,” in Pacific Diaspora: Island Peoples in the United States and Across the Pacific, eds. Paul Spickard, Joanne L. Rondilla, and Debbie Hippolyte Wright (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2002), 309-321. 7 Donald Roden, “Baseball and the Quest for National Dignity in Japan,” in Baseball History from Outside the Lines: A Reader, ed. John E. Dreifort (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 298. 8 John B. Foster, ed., Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide, 1910 (New York: American Sports Publishing, 1910), 303; Francis C. Richter, ed., “Collegiate 1909 Invasion of Japan,” in The Reach Official American League Baseball Guide for 1910 (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Co., 1910), 481; Robert Obojski, The Rise of Japanese Baseball Power (Radnor, Pa.: Chilton Books, 1975), 4, 7-9, 10-14. 9 Pat Page to Amos Alonzo Stagg, 6 October 1910, folder 3, box 63, Amos Alonzo Stagg Papers, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois; Pat Page to Amos Alonzo Stagg, 14 October 1910, folder 3, box 63, Stagg Papers. 10 Leonard Wood to Bishop Brent, 24 March 1910, box 9, Charles H. Brent Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C [hereafter LC]. 11 Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 226. 12 Julius Pratt, Expansionists of 1898: The Acquisition of Hawaii and the Spanish Islands (Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1936), 5, 301-329. 13 Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 97-99, 105, 109, 114; Louis A. Perez, Jr., On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality and Culture (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 75-77, 90. 14 Cited in Perez, Jr., On Becoming Cuban, 76; El Base-Ball, 9 April 1893, p.3. 15 Perez, Jr., On Becoming Cuban, 322-323 [QUOTATIONS]. 16 Box “Cuba” [1899-1902], Leonard Wood Papers, LC; Allan R. Millett, The Politics of Intervention: The Military Occupation of Cuba, 1906-1909 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1968), 34-38; Charles E. Magoon, Republic of Cuba: Report of Provisional Administration (Havana: Rambla and Bouza, 1908), 349-350; Louis A. Perez, Jr., Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997), 128 [QUOTATION]. 17 Perez, Jr., On Becoming Cuban, 260; Chicago Tribune, 2 January 1910, sec. 3, p.1. 18 Ivan Musicant, The Banana Wars: A History of United States Military Intervention in Latin America from the Spanish-American War to the Invasion of Panama (New York: Macmillan, 1990), 67-71; David Healy, Drive to Hegemony: The United States in the Caribbean, 1898-1917 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988), 210-216; Perez, Jr., Cuba and the United States, 137-140; idem, On Becoming Cuban, 177-198, 220-255; Gonzalez, Pride of Havana, 190-196. 19 Musicant, Banana Wars, 71-78; Healy, Drive to Hegemony, 203-208. 20 Gonzalez, Pride of Havana, 48, 71, 225-251, 407n7; Perez, Jr., On Becoming Cuban, 274; idem, Cuba and the United States, 209-214; Paula J. Pettavino and Geralyn Pye, Sport in Cuba: The Diamond in the Rough (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1994), 36-37. 21 Box General Orders, Porto Rico, 1898-1900, volume 1, Leonard Wood Papers, LC; Jorge Duany, The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 202), 65121, 70 [QUOTATION]. 22 Military Orders Having Force of Law by Commanding General, Government of Porto Rico, 1898-1900, Vol. II, pp. 76-115, Records of the Department and District of Puerto Rico Decimal Files 395.15.1, Records of United States Army Overseas Operations and Commands, 1898-1942, Record Group 395, National Archives, Washington, D.C. (hereafter NARA); Peter C. Stuart, Isles of Empire: The United States and Its Overseas Possessions (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1999), 361-362. 23 Box General Orders, Porto Rico, 1898-1900, vol. 1, Wood Papers; Gervasio Luis Garcia, “‘I Am the Other’: Puerto Rico in the Eyes of North Americans, 1898,” Journal of American History 87 (2000): 39-64; Stuart, Isles of Empire, 28, 59n16. 22 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM 24 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 1995), 1; A.C. Sharpe, Report to Adjutant General, 25 July 1900, Records of the Department and District of Puerto Rico Decimal Files 395.15.1, Records of United States Army Overseas Operations and Commands, 1898-1942, Record Group 395, NARA. 25 W.G. Coxhead, Report of the Physical Director of the YMCA, 1 October 1915-30 September 1916, p. 9, Young Men’s Christian Association Archives, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota (hereafter YMCAA). 26 Dr. P.S. Spence to Sir, 23 September 1915, box 931, Records Relating to the Philippine Islands, 1898-1939 Decimal Files 350.3, Records of the Bureau of Insular Affairs, 1868-1945, Record Group 350, National Archives, College Park, Maryland (hereafter NARA II); W.G. Coxhead, Report for Quarter Ending 30 June 1915, YMCAA; idem, Report of the Physical Director of the YMCA, 1 October 1915-30 September 1916, YMCAA; idem, Report Ending 30 September 1914, no page [QUOTATION], YMCAA. 27 Porto Rican Interests: Hearings Before the Committee on Insular Affairs, House of Representatives (Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1919), 9-10; Healy, Drive to Hegemony, 267; Stuart, Isles of Empire, 99. 28 Jacobson, Whiteness of a Different Color, 78; Brinton cited in Baker, From Savage to Negro, 27. 29 Leonard Wood to Bishop Brent, 4 March 1910, box 9, Brent Papers. 30 Paul Kramer, “Reflex Actions: Social Imperialism between the United States and the Philippines, 1898-1929,” paper presented at 117th Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association, Chicago, 2-5 January 2003, notes in possession of author. 31 Dean C. Worcester Papers, Bentley Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. For examples, see Dean C. Worcester, “Field Sports Among the Wild Men of Luzon,” National Geographic, March 1911, pp. 215-267; idem, “The Non-Christian Peoples of the Philippine Islands,” National Geographic, November 1913, pp. 1157-1256; idem, The Philippines: Past and Present, 2 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1914), 2: 514 [QUOTATION]. 32 Harold Seymour, Baseball: The People’s Game (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 324325. 33 Lewis E. Gleeck, Jr., American Institutions in the Philippines (Manila: Historical Conservation Society, 1976), 39. 34 Charles Moore, ed., Plan of Chicago (Chicago: Commercial Club, 1909), 29 [QUOTATION]; Ninth Annual Report, 1910 (Manila: n.p., 1910), no page, box 3, Worcester Papers. 35 Series 1, 165, 194-195, 356-357, 499, 579-580, 596-599, 629-630, 641, vol. 15, Daniel Burnham Papers, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago; Thomas Hines, Burnham of Chicago: Architect and Planner (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 20, 206-213; Stanley Karnow, In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines (New York: Random House, 1989), 16-17, 211-215; Jan Beran, “Americans in the Philippines: Imperialism or Progress Through Sports?” International Journal of the History of Sport 6 (1989): 62-87. 36 Philippines Correspondence Reports, 1911-1968, Administrative Reports file, YMCAA. 37 W.W. Marquart, Director of Education, Manila, 25 October 1916, box 931, Records Relating to the Philippine Islands, NARA II; Celia Bocobo-Olivar, History of Physical Education in the Philippines (Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines, 1972), 46-48, 54, 71; W.T. Ross, “Education in the Philippines,” p. 17, folder 13, box 142, Fred Eggan Papers, University of Chicago, Chicago; Elwood Brown, Annual Report, 1 October. 1912-1 October. 1913, YMCAA. 38 Philippines, International division 167, local associations, 1906-1973, Manila file, YMCAA, on segregation policies; Elwood Brown, Annual Report, 1 October. 1914-1 October. 1915, YMCAA; Kenton J. Clymer, Protestant Missionaries in the Philippines, 1898-1916: An Inquiry into the American Colonial Mentality (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 66, 92. 39 Pancho Villa file, Boxing Hall of Fame, Canastota, New York; T.S. Andrews, ed., Ring Battles of Centuries and Sporting Almanac (n.c.: Tom Andrews Record Book Co., 1924), 29. 40 Linda Nueva Espana-Maram, “Negotiating Identity: Youth, Gender, and Popular Culture in Los Angeles’s Little Manila, 1920s-1940s” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Los Angeles, 1996), Spring 2006 23 JOURNAL OF SPORT HISTORY 118-126; Roger Mooney, “Going Home a Hero: How Ceferino Garcia Finally Realized His Dreams,” Ring, April 1994, pp. 26-28, 60, in Ceferino Garcia file, Boxing Hall of Fame; School News Review, 1 October 1935, p. 8, box 1187, Records Relating to the Philippine Islands, NARA II. 41 Bocobo-Olivar, History of Physical Education in the Philippines, 49. 42 Ibid., 50. 43 Ibid., 48. 44 School News Review, 15 July 1934, p. 8, box 1187, Records Relating to the Philippine Islands, NARA II ; J. Truitt Maxwell to Elwood S. Brown, 18 April 1922, 1920-1923 correspondence file, YMCAA; Earl Carroll, Sec. of Luzon, Annual Administrative Report, 1932, YMCAA; E. S. Turner to Frank V. Slack, 7 August 1935, 1930-1936 correspondence file, YMCAA. 45 Robert C. Schmitt, “Some Firsts in Island Leisure,” The Hawaiian Journal of History 12 (1978): 99-119; The Islander, 6 August 1875, p. 145; The Islander, 20 August 1875, p. 160, both in Hawaii file, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York. See Elizabeth Buck, Paradise Remade: The Politics of Culture and History in Hawaii (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993); and Pratt, Expansionists of 1898, 37-110 on political developments. 46 Pratt, Expansionists of 1898, 217. 47 Ronald Takaki, Pau Hana: Plantation Life and Labor in Hawaii, 1835-1920 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1983), 127-132. 48 Franks, Crossing Sidelines, Crossing Cultures, 58-61; idem, Hawaiian Sports in the Twentieth Century, 24-32; idem, “Baseball and Racism’s Traveling Eye: The Asian Pacific Experience,” in The American Game: Baseball and Ethnicity, eds. Lawrence Baldassaro and Richard A. Johnson (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), 177-196. 49 Ben R. Finney, “The Development and Diffusion of Modern Hawaiian Surfing,” Journal of the Polynesian Society 69 (1960): 315-331; Harold H. Yost, Outrigger Canoe Club of Honolulu, Hawaii (Honolulu: Outrigger Canoe Club, 1971). 50 Franks, Hawaiian Sports, 40-44; Sandra Kimberley Hall and Greg Ambrose, Memories of Duke: The Legend Comes to Life (Honolulu: The Bess Press, 1995). 51 Franks, Hawaiian Sports, 21, 54, 57, 60; T. Takasugi to A. Alonzo Stagg, 20 July 1910, folder 3, box 63, Stagg Papers; Takaki, Pau Hana, 104 [QUOTATION]. 52 John H. Nankivell, The History of the Twenty-Fifth Regiment United States Infantry, 1896-1926 (Denver, Colo.: Smith-Brooks Printing, 1927; reprint ed., Ft. Collins, Colo.: The Old Army Press, 1972), 163-165, 171, 173. 53 Franks, Hawaiian Sports, 52-59, 66-68; A.A. Kempa, A Survey of Physical Education in the Territory of Hawaii, 1930, pp. 26-28, Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawai‘i; Honolulu Recreation Commission, A History of Recreation in Hawaii (Honolulu, Hawai‘i: Honolulu Recreation Commission, 1936), 27, 47, 65, 100. 54 Mansel G. Blackford, Fragile Paradise: The Impact of Tourism on Maui, 1959-2000 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001); Buck, Paradise Remade, 171-188, 177 [QUOTATION]. 55 Blackford, Fragile Paradise, 58-74, 95-110, 202-230; Buck, Paradise Remade, 180-188; Kauanoe Kamana and William H. Wilson, “The Tip of the Spear: Hawaiian Educators Reclaim a Cultural Legacy,” Teaching Tolerance 21 (2002): 20-24; Joe Kane, “Arrested Development,” Outside, May 2001, pp. 68-78. 56 Alan M. Klein, Sugarball: The American Game, the Dominican Dream (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991), 110. 57 Ibid., 29; Alan M. Klein, “Culture, Politics, and Baseball in the Dominican Republic,” Latin American Perspectives 22 (1995): 111-130. 58 Michael Knisely, “Everybody Has the Dream,” Sporting News, 21 February 2001, <http:// www.findarticles.com> [10 December 2001]; Don Le Batard, “Next Detour,” ESPN Magazine, 24 December 2001, pp. 105-111. 59 Lester D. Langley and Thomas Schoonover, The Banana Men: American Mercenaries and Entrepreneurs in Central America, 1880-1930 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1995); Richard McGehee, 24 Volume 33, Number 1 SPORT, COLONIALISM, AND UNITED STATES IMPERIALISM “The King and His Court: Early Baseball and Other Sports in Nicaragua,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the North American Society for Sport History, Auburn, Alabama, 24-27 May 1996, in possession of author; idem, “Sport in Nicaragua, 1888-1926,” in Sport in Latin America and the Caribbean, eds. Joseph L. Arbena and David G. La France (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 2002), 175-205, 184 [QUOTATION]. 60 McGehee, “Sport in Nicaragua,” 175-205. 61 Musicant, Banana Wars, 286-333; Joel Zoss and John Bowman, Diamonds in the Rough: The Untold History of Baseball (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1996), 405-406; Randy Wayne White, “Far From Home Plate,” Outside, October 2001, p. 51. 62 Healy, Drive to Hegemony, 27-28, 77-98; Musicant, Banana Wars, 79-136; Julie Greene, “Spaniards on the Silver Roll: The U.S. Government, Liminality, and Labor Troubles in the Panama Canal Zone,” Newberry Library Labor History Seminar, Chicago, 21 September 2001, in possession of author. 63 Healy, Drive to Hegemony, 227; Panama Al Brown file, Boxing Hall of Fame. 64 Jeremy Greenwood, “Roberto Duran . . . Latin Ambassador of Macho,” World Wide Boxing Digest, pp. 4-5, clipping in Roberto Duran file, Boxing Hall of Fame. 65 Musicant, Banana Wars, 390-417; Peter C. Bjarkman, Baseball with a Latin Beat: A History of the Latin Game (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1994) 347-384. 66 Anonymous, “Wards of the United States: Notes on What Our Country Is Doing for Santo Domingo, Nicaragua, and Haiti,” National Geographic, August 1916, pp. 143-177, 162-163 [QUOTATION]. 67 Mary A. Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915-1940 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001). 68 J.A.C. Gray, Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration (Annapolis, Md.: United States Naval Institute, 1960). 69 Bruce Feldman, “Rock Star,” ESPN Magazine, 20 November 2001, pp. 50-54. 70 <http://basketball.sportingpulse.com/oceania/background.shtml> [2 April 2002]; <http:// www.oceaniasport.com/onoc/index.cgi?sID=3&intArticleID=37&det=1> [15 April 2007]. 71 Stuart, Isles of Empire, 241, 243, 266, 331; Wei and Kamel, eds., Resistance in Paradise, 111-114, 117. 72 Vicente M. Diaz, “Fight Boys ‘til the Last . . .”: Island Football and the Remasculinization of Indigeneity in the Militarized American Pacific Islands,” in Pacific Diaspora, eds. Spickard, Rondilla, and Wright, eds., 169-194. 73 Stuart, Isles of Empire, 46-54, 105-106, 116-117, 161, 172, 174n11; Hazel McFerson, The Racial Dimension of American Overseas Colonial Policy (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1997), 112. 74 Diaz, “Fight Boys ‘til the Last.” Spring 2006 25