Community College Online

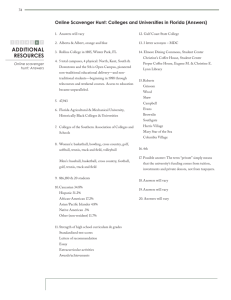

advertisement