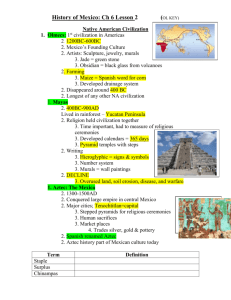

MESTIZO AMERICA

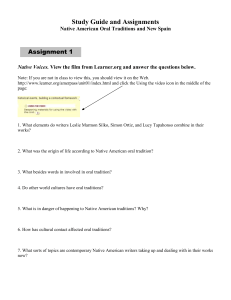

advertisement