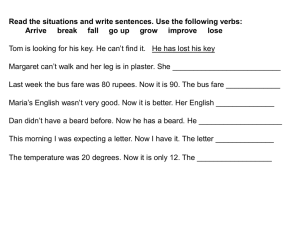

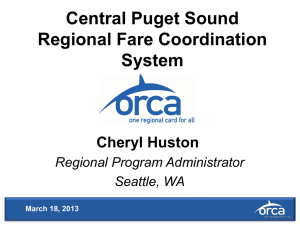

bus transit fare collection practices

advertisement