Colonel House in Latin America

advertisement

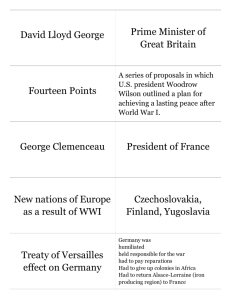

Colonel House in Latin America The Laboratory of Progressive Internationalism Peter Russell Junior Greenwich High School 2013 Riverside, CT pjr2442@gmail.com Introduction Not often in the study of American history does one find a character as intensely interesting and unique as Colonel Edward Mandel House. House was, perhaps, the most influential American statesman of his time, a private citizen who, as a close personal friend and trusted confidante of President Woodrow Wilson, stood at the crossroads of the 20th century’s most important and far reaching decisions.i Colonel House, as is evidenced by his obscure legacy, was not in the business of politics for fame or notoriety. Never having had a title or an official U.S. government position, Colonel House remains, in many cases, a footnote in textbooks of American and European history, despite having exercised significantly more influence than all but a few of his counterparts. The actions taken by Colonel House, often understated by historians, had a major impact on the course of history.ii Among his many achievements, House preserved the sovereignty of Mexico from intrusive European hegemony, as the country struggled through the ten years of its revolution. House then stood at the forefront of the modern Anglo-American relationship, developing the necessary rapport with Foreign Minister Edward Grey which strengthened the Anglo-American relationship in the days leading up to World War I and ultimately blossomed into the “special relationship” of President Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. House, as a diplomat, politician and advisor, complemented President Wilson’s personality, acting as a levelheaded force to calm an often-bombastic and occasionally ill-tempered Head of State. In this way, House saved Wilson from repeating the political and diplomatic errors of his predecessors, the mixed legacy of Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet and William Howard Taft’s “Dollar Diplomacy.” House preserved the progressive image of Wilsonian diplomacy, helped to avert a number of military adventures and worked unceasingly for peace right up to America’s entry into World War I.iii House’s pioneering work on a Pan-American charter foreshadowed his crowning achievement: his key role in the formulation and promulgation of the League of Nations, a role far more critical than generally realized.iv In fact, he provided Wilson with the idea for the policy, charted the League’s specifics, and provided Wilson and the world with the cogent reasons and resolve to pursue this vision of international cooperation. In effect, Colonel House transformed Woodrow Wilson into the President having the most influence on hemispheric external policies since James Monroe. House’s contributions ushered America unto the world stage and linked the domestic progressive agenda with the nation’s foreign policy. House remains, to this day, frequently overlooked and underappreciated in the histories of American Foreign policy. Beyond a doubt, House ushered American diplomacy onto the global stage, leading a new wave of internationalism that would rise to dominate the progressive movement and 20th century foreign policy for decades to come. The Relationship Between House and Wilson To understand Colonel House and his legacy, it is important to discuss the meaningful and powerful rapport that House shared with Woodrow Wilson. In this respect, House is arguably unique. He occupied a role in Wilson’s administration that blurred the lines between advisor and friend, and more closely resembles a mentor and guiding hand.v Colonel House advised Wilson on almost every aspect of his life, from personal relationships to policy matters. He met Wilson in 1911, arriving on the scene with a reputation as an incomparable campaign manager who had secured the election of several Democratic governors in Texas.vi The two men bonded immediately, in complete agreement on a wide range of issues and finding total comfort in each other’s company. At the conclusion of the meeting, Wilson asked House to advise his Presidential campaign. Upon Wilson’s victory, House was offered any position he desired in Wilson’s cabinet, with the exception of Secretary of State (that position was reserved for Democratic loyalist William Jennings Bryan).vii Colonel House declined the honor, however, choosing instead to serve “wherever and however I am needed by the President.” In this way, House chose influence over fame, real power over a title. He always wanted to control things behind the scenes and have a profound impact on the course of history. Having the President’s ear, and his confidence, enabled House to influence the foreign policy of the United States. Often standing at the President’s side and frequently living in the White House itself, he achieved a great deal of success. He advised the President on a wide range of issues and was instrumental in seeing that the most important parts of the President’s programs were implemented. As George and George’s Personality Study points out, both House and Wilson brought something to the partnership that each needed desperately.viii Wilson was erratic and undiplomatic while House served to temper Wilson’s raw emotions. Yet, without access to presidential power, House would have existed as an advisor without portfolio, a kingmaker without the requisite king, making House’s dependency on Wilson equally acute. The two were complementary, and were almost alter egos. Unfortunately, with the passage of time, the Colonel’s contribution has received much less appreciation than it rightfully deserves.ix What needs to be re-examined and re-assessed is the scope of House’s influence in encouraging Woodrow Wilson’s international aspirations and his role in executing the President’s vision for the future of both the industrialized and the developing world. It cannot be disputed that House had a great impact on Wilson’s policies, which, in turn, made a great impression upon the developing world: stabilization of the Government of Mexico, peace efforts in Europe, military intervention in World War I when all efforts at peace had failed, proposing the creation of the League of Nations, and representing the United States at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919, House was ubiquitous on the world stage, a private citizen, without an official capacity, molding foreign Heads of State to American positions. He eclipsed the de jure Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan. It is undeniable that the President had placed plenipotentiary authority in House’s hands, making him, in effect, the de facto Secretary. His legacy, no doubt, saved some of the world from itself, at least temporarily, and forever changed the predominant currents of international relations. The Conflict of Ideals and Business in Revolutionary Mexico Colonel House and President Wilson kept British oil interests from transforming Mexico into a puppet state, while protecting United States commercial and political interests and safeguarding American principles. The Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) was an opportunist’s dream, with frequent changes in the Federal Government, and with warlords outside the national capital controlling vast territories and dispensing oil exploration and mining franchises to the highest bidder. The Mexican people and their ineffective governments were the least important force driving the revolution in its early stages. Foreign diplomats were, by far, more influential, as their financial support and recognition were the keys to entrenched connections within Mexico’s corrupt bureaucracy. These connections and resources also enabled them to decide which upstart strongman would have the backing of the international community. American Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson was one of these wheeler-dealer diplomats. Ambassador Wilson had maintained a very close relationship not only with Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz but also with a number of revolutionary figures. It was generally believed that Wilson had received his appointment as ambassador due to the influence of the Guggenheim family.x The Guggenheim family held vast mining and smelting interests throughout the world, including the largest copper mining and smelting operation in Mexico. Having enjoyed the protection of President Porfirio Diaz (President of Mexico 1884-1911), they amassed one of the largest fortunes in the world. The overthrow of Diaz in 1911 by Francisco Madero (President of Mexico 1911-1913) represented a real threat to their investments. Consequently, they were viscerally opposed to President Madero and his reform policies. In addition, Madero competed directly with the Guggenheims, as he owned a large copper smelting company at the time of his election in 1910, making him an economic adversary as well as a political one. Therefore, with these factors influencing his calculus, Ambassador Lane supported the overthrow of Madero and the appointment of Victoriano Huerta as provisional President, with an understanding that Felix Diaz, nephew of former dictator Porfirio Diaz, would become president.xi This plan of succession was agreed to by the ambassadors of the major powers at a meeting at the American embassy. The “Pact of the Embassy” provided for the removal from office and exile of Madero and Vice President Jose Maria Pino Suarez.xii In what Mexicans call la decena tragica, both Madero and Suarez were assassinated by military officers loyal to and subsequently promoted by Huerta.xiii There was no doubt that Ambassador Wilson had blood on his hands. Nonetheless, his connections in such a volatile country made him indispensable; without a suitable replacement at the time, Wilson was forced to let him remain. In the meantime, however, Wilson sent a number of Presidential advisors to keep him apprised of the situation, and dispatched Colonel House, as well, to run diplomatic interference.xiv These events took place during the lame duck presidency of William Howard Taft and served as a source of major concern to President-elect Wilson who was forced to watch from the sidelines. In fact, early in 1913, Wilson had sent Colonel House on a factfinding mission to Mexico for the sole purpose of evaluating Madero’s suitability as President of Mexico. House had reported to Wilson, in January of that year, about Madero’s good character, and his worthiness of receiving United States support and sympathy.xv In many ways, Madero’s nationalist campaign represented many of the progressive ideals which Wilson and House espoused. Madero’s anointed successor Victoriano Huerta was just the opposite; he was corrupt and in fief to the economic oligarchs. In addition, there was considerable evidence that he had been bought and sold by British interests. Wilson and House feared that the British had exclusive access to the man and, consequently, were not prepared to support a dictatorial, plutocratic regime well within the United States sphere of influence. On a moral and a practical level, the United States, as Edward Grey described, was resolved that “Huerta could not stay.”xvi American fears that the British were conspiring to convert Huerta’s government into a puppet regime can be traced to that modern root of all evils: oil. Weetman Pearson, an Englishman and 1st Viscount Cowdray, had come to dominate the Mexican railway system. He had come to Mexico in 1889 at the request of former dictator Porfirio Diaz, who wanted him to build a railway across Mexico as part of his plans for industrialization. After taking a wrong connection during one of his trips, Lord Cowdray stumbled across a small town in Texas, wild with the oil craze. Thinking that the oil could replace coal and power the Mexican railways, Lord Cowdray bought a vast amount of acreage of land with promising geological structure. He eventually struck oil on the Mexican portion of his holdings at Potrero de Llano in November of 1910.xvii And, from that first wildcat well, he built the largest oil empire in Latin America. To some sycophants, he was known as the Rockefeller of Mexico. Then, Madero appeared on the scene, an implacable enemy of the old regime and its minions. As one of his first moves, the revolutionary announced his plans to nationalize the oil industry, the railways, and other critical industries in Mexico, many of which were foreign especially British, owned or controlled.xviii Huerta, in the aftermath of the coup, was in the market to sell protection and, in return, wanted British money and recognition. Ultimately, he did receive de facto provisional recognition. In the early months of his regime, Huerta was already well underway in the process of reversing Madero’s nationalizations. Added to the moral outrage over Madero’s assassination was Washington’s fear that Great Britain and its bailiff, Lord Cowdray, would get the biggest, if not the only, cut of the Mexican pie.xix President Wilson saw that British business interests in Mexico, represented by Sir Lionel Carden, British Ambassador to Mexico, and led by Lord Cowdray, were poised to hijack the Mexican government.xx Fortunately for American interests, Britain had only extended provisional recognition in an era when the term provisional had a strictly limited meaning. There was still time to deter formal recognition. Recognition past the provisional level would have serious consequences, primarily destroying the unified diplomatic front that Wilson and House had managed to achieve. Up to that point, no major power had yet extended the formal recognition that the Huerta government desired and was prepared to pay for, and the Wilson administration wanted to keep it that way. Wilson and House could not afford to have Britain break ranks and give Huerta what he desperately wanted.xxi In Europe, legal recognition was never viewed as the equivalent of moral approval, but rather was rooted in realpolitik. Wilson and House’s views were radically different; they were convinced that formal recognition conveyed not only approval but also carte blanche for business, mostly corrupt, as usual. The United States believed it must prevent Britain from permitting the perversion of Mexican democracy in return for oil concessions. The United States was not about to stand idly by and let that happen.xxii President Wilson sent Colonel House, a private citizen but with an unofficial role as minister plenipotentiary, to stop the British lion in his tracks and he did nothing less. After negotiations with the British foreign Ministry, House succeeded in defusing the crisis. Britain agreed to withhold formal recognition, meaning that there would be no preferential treatment of British companies at the expense of American competitors.xxiii It had even greater significance; it would render Huerta’s government increasingly unstable and subject to change. The President and Colonel House knew that, without British support and with almost no other formal or informal international foreign backing, Huerta was in no position to continue ruling Mexico. His days were numbered, which was exactly what the United States wanted. House and Wilson solved the dispute between the UK and the US over Panama toll exemptions, breaking ranks with the Democrats by doing so, both to placate the British for changing their policy on Mexico, and also out of righteousness, believing that such an exemption violated a pre-existing treaty. Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary, had already made it clear that Mexico was too important to Great Britain to allow it to blindly follow the United States demands. The Empire, he decided, was in full right “take its own line” of approach.xxiv In order to turn British policy into reality, Grey wanted to resolve a standing conflict that Britain had with the United States over the Panama Canal. The United States Congress, with its Constitutional responsibility for imports and import duties, had imposed a tariff on goods passing through the Panama Canal in foreign vessels. American shipping was exempted from the tax. Whether he knew it or not, Grey had an ally in the person of President Wilson. While Wilson was very much against the exemption for American ships, he had to deal with Congress, whose members, especially the Democrats, were strongly in favor of the exemption.xxv Senators of Irish-American descent were especially vociferous in their opposition to an exemption for Great Britain, while claiming, hypocritically, that they supported an “open canal” policy.xxvi The exemption also appeared to be in direct violation of the ratified Hay-Pauncefote treaty of 1901, which promised equal treatment of all nations’ trade with regards to the canal. Colonel House wrote about his concurrence with Wilson: “I asked him concerning his views in regard to the Panama Canal tolls controversy with Great Britain. I was glad to find that he took the same view that I have, and that is that the clause should be repealed.”xxvii With the benefit of hindsight, it appears that a diplomatic agreement was there for the making. House set up a meeting with Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, at the first possible opportunity in the sweltering summer of 1913. Their meeting led to a general agreement on a number of important matters. Grey promised that the recognition provided to Huerta was merely provisional, and that, given Huerta’s numerous assurances that he would not run for President, if he did run for office, Huerta’s government would not be recognized by Great Britain. House, in turn, guaranteed that the Panama tariff issue was of utmost priority. However, given the small margin of support that President Wilson was able to command in the U.S. Senate, the issue would possibly jeopardize the progress of other important legislative measures. Therefore, House suggested that, for the time being, the British stick to provisional recognition, and that, given some time, the he, Wilson and their Congressional allies would repeal the tariff exemption after other programs were legislated. Grey accepted the arrangement, and for the moment, the United States and Britain were able to act with unity on an important matter of foreign policy, and maintain the united American-European front on Mexican affairs.xxviii January of 1914 saw Wilson bring the matter up with the Congress, and June saw the repeal of the special exemption become law.xxix Meanwhile, the British Foreign Office instructed Sir Lionel Carden (the pro-Huerta British Ambassador to Mexico), to “not take steps to interfere in any way with Wilson’s anti-Huerta policy in Mexico,” upholding Grey’s end of the bargain.xxx On October 27, 1913, Woodrow Wilson gave a speech to the Southern Commercial Congress in Mobile, Alabama. Here, he rallied once again against “interest groups” that threatened progressive programs.xxxi However, in this speech, Wilson expanded his definition to include international capitalist circles. In this instance, Wilson specifically referred to European interests in Mexico, which had sought to pervert democracy for profit.xxxii “Say no to Huartists” became part of his political rhetoric. This speech clearly suggested that Wilson had won this fight. If Wilson and House had not acted, the British were likely to have recognized the Huerta government in Mexico, destroying the united front and crushing moral diplomacy in Mexico. It was also almost certain that control of Mexican oil development would have fallen under the complete control of Lord Cowdray’s mining operations, which would have proved disastrous for American oil companies. President Wilson and Colonel House’s first diplomatic initiative had met with complete success, a first step in the long road to democratic government in Mexico. As expected, Huerta failed to maintain political power, and was ousted by armed insurrection the following July of 1914. Progressivism had been extended beyond domestic policies, and the support for democratic ideals in other countries defined a new approach to international relations for the United States. Hints of the principle of “selfdetermination,” a concept destined to dominate U.S. foreign policy in the aftermath of World War I, date to these day of American diplomacy in Mexico. House did not allow personal ambition or interests to influence his positions at the negotiating table.xxxiii xxxiv Rather, he stood for American ideals of freedom and democracy. Houses ABC’s: Pan-America and the Creation of Article X of the League House found himself obsessed with the possibility of a Pan-American Treaty, the treaty that had eluded his predecessors despite their determined efforts. The Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, as well as former Secretary of State James Blaine, both had unsuccessfully pursued a super-national government for the countries of North and South America. Their efforts had met with little success because of determined opposition in the United States, primarily from isolationists who unwilling to commit U.S. military and economic power to promote the sovereignty of its neighboring countries. A PanAmerican Union, at least in name, surprisingly had resulted from this three decade long effort; however, the Union itself was largely powerless, and U.S.-South American relations, in general, had deteriorated after an 1891 US invasion of Chile as retaliation for treatment of US military personnel at Valparaiso. The invasion itself and the peace terms that followed solidified the opinions of South American governments and citizens who were already convinced that the United Sates had replaced Spain as an imperialist power. To them, this episode was but further confirmation that their northern neighbor was nothing more than an unjust, aggressive bully. In the aftermath of the Mexico crisis, Colonel House saw a genuine need for the United States to intervene to prevent neo-colonial adventures on the part of European powers. — in short a re-assertion of the Monroe Doctrine. The true motives for this renewal from the US-side remain a subject of debate. Nonetheless, ideas of a Pan-American Union were undoubtedly renewed, with Colonel House leading the charge. In 1914, House had called for the “ABC Powers,” Argentina, Brazil and Childe, to mediate a dispute. The Niagara Conference, as it is now known, narrowly avoided war between the US and Mexico over an incident earlier in the year, the Tampico Incident.xxxv The successful mediation provided the US government much needed credibility among the South American nations, and partially ameliorated the discredited US image. As indication of this success, the Chilean Minister wrote to Colonel House of “the President's success in the Mexican difficulties-turning, as he did, a situation fraught with difficulties and danger to our American relations into a triumph of PanAmericanism.”xxxvi It was about this time in August 1914 that the Great War broke out, a failure of European diplomacy of monumental consequences that House blamed largely on a lack of transparency, dialogue and cooperation amongst the imperial powers. Looking to keep the Americas from experiencing the same unfortunate fate as Europe, House felt a new sense of urgency to pursue permanent Pan-American policies and erect permanent instruments of Pan-American cooperation. In the summer, House met with Wilson and urged him, “to pay less attention to his domestic policy and greater attention to the welding together of the two western continents.”xxxvii Wilson immediately agreed, almost without hesitation, confirming his commitment to a legacy of American involvement in maintaining world peace. While House had advised Wilson of this change in course verbally, he now sent Wilson a letter reinforcing his points.xxxviii Still unwilling to let matters rest without complete agreement and immediate adoption on the part of President Wilson, House drew up a plan to present to the President later that month at the White House. House, as he recounted in his diary, sought “nothing less than a rather loose league of American states which should guarantee security from aggression and furnish a mechanism for the pacific settlement of disputes.xxxix This “league” would be led chiefly by the United States and the ABC Powers, and would agree to two things in particular: first, unquestionable sovereignty over national territory; second, government ownership of “munitions of war.” At the urging of House, the President wrote these ideas down by hand, and immediately typed them out, “excited in his enthusiasm,” before providing the document and its wording to the Colonel for immediate use in negotiations with South American ambassadors.xl The wording of these resolutions bears resemblance with what would become Article X of the League of Nations charter.xli While historians have credited Wilson for conceiving the creation of the League of Nations, the idea and, perhaps, even the wording of the most critical and historic articles of the League of Nations charter were a product of Colonel House, a private US citizen. From this time onward, House focused on negotiations, and did so with surprisingly furious efficiency. A meeting was held immediately, and the Argentine Ambassador fell in love with the proposal, even asking to keep the original copy that Wilson had typewritten, convinced it would become an important historical document. The Brazilian Ambassador, da Gama, was equally convinced and almost immediately embraced the covenant that House had constructed and Wilson had typewritten.xlii The Chilean Ambassador, however, was reluctant to sign on, as they stood in the midst of border dispute with Peru.xliii The agreement implied renouncing war as a means to solve conflict within the proposed League, which meant that Chile would not be able to enforce its claim to land disputed with Peru. However, House was able to convince the ambassador that such claims would be settled quickly, as there were other disputes in territory between Costa Rica and Peru, and that all disputes would be worked out before Chile surrendered its right to wage war on Peru.xliv As a result, within the day, House had won over the representatives of the ABC powers, doing so masterfully. As a testament to his work and to the extent to which persuasion had won over the diplomats, the normal rules governing the speed of diplomatic response did not apply; the Brazilian Ambassador secured the approval of his government to the treaty less than a week after the initial meeting with House, with the Argentine Ambassador following not long after.xlv The treaty required a certain degree of political stability to be had in all participatory nations, so that the provisions concerning munitions control could be enforced. This was a sort of “Catch-22,” as much of Central and South America at the time was composed of smaller, independent states still in the process of chartering their future government, and were not necessarily in a position to ratify a Pan-American Treaty so radical as the Colonel’s. Furthermore, while it was officially supported by the State Department as a consequence of the President’s complete endorsement, Secretary of States William Jennings Bryan himself did not find the treaty to be necessary.xlvi Bryan had recently adopted accords with the South American nations, which, while not as inclusive, he thought were sufficient to stave off conflict. They provided for a “cooling off” period before military action could commence, during which neutral arbiters would be brought in to get both sides to the negotiating table. Anything more, Bryan thought, was superfluous.xlvii As a result, even though the treaty negotiations had received ambassadorial approval, the respective governments did not actively pursue them. When House turned the negotiations over to the U.S. State Department, there was no further progress and the fact that he was a private citizen came home to roust. The Original “Special Relationship” The Colonel established the special relationship through his cordial approach to diplomacy, which was appreciated by Edward Grey, British Foreign Minister, and gave the Anglo-American relationship an openness, frankness and efficiency which it had never before contained. The agreements concerning Mexico and the Panama Canal tolls inaugurated a new awareness of mutual interests between the United States and Great Britain. Prior to Colonel House’s involvement, British Foreign Minister Sir Edward Grey and his associates at the Foreign Office were unsure of American resolve on these issues. After all, Ambassador Lane Wilson’s involvement in the removal of Francesco Madero clearly demonstrated that he had far different political connections and goals than President Wilson. In fact, prior to the agreements made by House and Foreign Minister Grey, the British government had every reason to be skeptical about American policy, and was quite skeptical in actuality.xlviii These doubts, however, quickly evaporated. Grey and House immediately became friends. House’s frankness and openness, his clearly demonstrated lack of ulterior motives, all played a major role in the development of Grey’s confidence and trust. Their very first meeting is described in the Intimate Papers as one in which the two men expressed their views on diplomacy “as a means by which the representatives of different states could discuss frankly the coincidence or the clash of national interests and reach a peaceable understanding...like a personal business.”xlix This frank discourse between the two men who were friends and remained so is remarkable. In a meeting between Sir William Tyrrell, one of Grey’s confidants, Colonel House and the President, the Panama tolls came up spontaneously as a topic of conversation. Wilson candidly acknowledged that the current state of affairs was a flagrant violation of treaty on the part of the United States; Wilson assigned the blame to “Hibernian patriots who always desired a fling at England,” emphasizing that the one person behind most of the opposition was New York Senator O’Gorman. The President caricatured him as “an Irishman contending against England rather than as a United States Senator upholding the dignity and welfare of this country.” Later, Tyrrell said to House that, if “veteran diplomats had heard us, they would have fallen in a faint,” all the while thanking House for the interview. Tyrell had “never before had such a frank talk about matters of so much importance.”l A new level of openness and trust had emerged from the prior days of unproductive bickering, an unquestionably novel epoch of AngloAmerican relations. This cordiality, shared by diplomats of both Great Britain and the United States, led ineluctably to the development of a special relationship between the two nations. While their primary responsibility was to represent the positions of their respective governments, empires, these diplomats were kind, respectful and friendly with their counterparts, which made innate trust come all more naturally. For the first time, nations were working not just out of nationalist interests, but out of the feeling of a common bond, which has influenced Anglo-American relations to this day. From the repeal of the special exemption in June of 1914, “the United States Government could count upon the sympathy of Sir Edward Grey.”li The “special relationship” long predates the cooperation of Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt; rather, it had its initiation in the early days of the Wilson administration and at the behest of a remarkable private citizen, Colonel Edward House. The Bottom Line: How House and Wilson Changed the Progressive Image President Wilson’s tenure marked the end of the progressive era. While this implies that the ideas of the Age of Wilson were not immediately continued by his conservative Republican successors, it signifies that Wilson, and to a great extent Colonel House, had the last opportunity to define the core of the progressive movement. The Federal Reserve entered the financial sector as an organ separate from Congress to regulate all-important monetary policy, promote opportunity, equality and stable growth in American markets. While the Federal Reserve System and other regulatory agencies of the era limited the pace at which rapid capital growth could take place, they also assured that this growth was stable and not the inevitable boom/bust. The Federal Reserve Act, in large measure, a product of Colonel House’s input continues to fulfill its purpose, regulate monetary policy and stabilize the economy one hundred years after the final negotiations to establish it. House provided the inspiration for the foundation and structure of the League of Nations, even going so far as to directly influence Article X, the most famous section of the charter. It was Article X that would lead to the eventual failure of the ratification battle in the Senate. Yet Article X also re-emerged in spirit in the United Nations, the more successful successor to the short-lived League of Nations. No matter your view, the modern UN attempts to and has even succeeded in defusing some a number of later conflicts, many of which might have led to war, an unachievable result as recently as a century ago. While it has many limitations, still, the UN has saved countless lives through peace-keeping operations and economic assistance. In this way, the legacy of Colonel House continues to benefit mankind to this day. Perhaps one of House’s more interesting contributions to the development of President Wilson’s political philosophy and to the progressive movement in general was his novel Philip Dru: Administrator, written and anonymously published in 1912.lii The book can be read as House’s political dream, and was largely adopted by Wilson as one of his favorite titles after House provided a copy for his 1912 Bermuda vacation.liii In the novel, the main character, Philip Dru, leads a democratic Western United States in a second civil war against the corrupt plutocratic Eastern seaboard, delivering the nation from the tyranny of big business in the process. Dru, upon seizing power, names himself Administrator of the Republic, institutes a number of reforms that resemble the Bull Moose platform of 1912, and vanishes.liv The novel embodies the Colonel’s progressive thinking, and foreshadows the crusade he and Wilson undertook in his later years as a warrior preacher of progressive ideals. It places emphasis, especially, on the altruistic side of progressive policy and the progressive reform movement, a message that resonated with Wilson. Dru, clearly the protagonist of House’s own views, was presented as selflessly looking to expand democracy to those areas of the world that did not have it, a cause seamlessly adopted by Wilson as well. The progressive movement was, by connection, equally influenced by the Colonel since its leader had been irreversibly indoctrinated. Yet to the Colonel and President, this altruism that comes with the progressivism of Philip Dru has a different definition relative to contemporary morality. While both men looked to promote democracy throughout the world, they looked to do so on their own terms. Each can be accurately portrayed as racist, as can be expected of many men of their era; Wilson would call the Germans “the Huns” in World War I, a popular term amongst American and British diplomats and officers during the War. House became so frustrated with Latin American affairs that he advocated intervention to teach the CentralAmericans how to self-govern and “create order out of chaos.”lv (Wilson too once remarked to a British diplomat that it was his responsibility to “teach the Latin Americans to elect good men.”lvi) Undoubtedly, each looked to further their own self-interest and beyond racial tendencies. Colonel House, despite his denials, owned land, silver stock and possessed other in Mexico, may explain his brief advocacy of intervention.lvii President Wilson undoubtedly had to temper his lack of sympathy for Latinos. Wilson had ambivalent feelings about capitalism, alternating between distaste and distrust, and admiration for corporations that looked beyond profit and projected what he felt were “American ideals overseas.”lviii In reality, the last progressive administration hedged their approach to foreign policy by defining self-determination as democracy on American terms. The effects this policy outlasted 1921, when the Age of Wilson came to an official electoral end, with House’s progressive foreign affairs policies, in one form or another, continuing to the present day. Conclusion Progressivism defied and re-defined the goals of politics in terms of ideals and moralistic reform. While, domestically, it struck against the inherent moral and fiscal corruption in big business, Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House expanded progressivism and their interpretation of its moral message to the international arena as well. Mexico provided the perfect testing ground for these new policies. Through Wilson and House’s diplomacy, American idealism, for better or worse, prevailed against the interests of international business in Mexico. As a consequence of this experience, House envisioned and presented to Wilson the framework for the Pan-American Treaty embodying a Congress to settle regional conflicts. The conduct of the Wilson administration, strongly influenced by Colonel House’s style of diplomatic negotiation, led to the construction of a bond of unprecedented cordiality and trust between the British Foreign Office and the United States, the inauguration of the famous “special relationship” between the United States and the United Kingdom. Mexico was a critical success for “Wilsonian” ideals and diplomacy, perhaps even providing Wilson and House with the necessary international savoir-faire for the looming conflict developing across the Atlantic. Above all, House’s experience with the Pan-American negotiations created the foundations of the League of Nations, his signature legacy. These policies were the beginnings of what Wilson would later characterize as an attempt to make the world “safe for democracy.” Ironically, it is this lofty goal for which Wilson is now famous—while House remains without the credit that is due him. Such is the fate that Colonel House himself probably would have chosen. i Robert H. Butts, "An Architect of the American Century: Colonel Edward M. House and the Modernization of United States Diplomacy" (PhD diss., Texas Christian University, 2010), 1, accessed June 4, 2013, ProQuest (UMI No. 3443311). ii George Sylvester Viereck, The Strangest Friendship in History: Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House (1976; repr., Praeger, 1976). iii Ibid. iv Ibid. v Alexander L. George and Juliette L. George, Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House: A Personality Study, Dover ed. (John Day Company, 1956; New York: Dover Publications, 1964), [Page #]. vi Arthur D. Howden Smith, "Mr. Smith's 'The Real Colonel House.,'" The New York Times (New York), June 23, 1918, accessed September 14, 2013, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10615FD3C5A11738DDDAA0A94DE405B888DF1D3. vii Robert H. Butts, "An Architect of the American Century: Colonel Edward M. House and the Modernization of United States Diplomacy" (PhD diss., Texas Christian University, 2010), 1, accessed June 4, 2013, ProQuest (UMI No. 3443311). viii Alexander L. George and Juliette L. George, Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House: A Personality Study, Dover ed. (John Day Company, 1956; New York: Dover Publications, 1964). ix Alexander L. George and Juliette L. George, Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House: A Personality Study, Dover ed. (John Day Company, 1956; New York: Dover Publications, 1964). x Godfrey Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 87. xi Ibid. xii Ibid. xiii Staff Presidencia, "Decena Trágica" [The Ten Tragic Days], Mexico: Presidencia de la Republica, last modified September 2, 2013, accessed September 15, 2013, http://www.presidencia.gob.mx/decena-tragica/. xiv xv Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand, 88. David S. Foglesong, America's Secret War Against Bolshevism (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 15. xvi Edward Grey, K.G, Twenty Five Years: 1892-1916 (New York, USA: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1925), 2:96-97. xvii Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand, 88. xviii xix Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand, 87. Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand, 88. xx House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 200. xxi Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand, 88. xxii Edward Grey, K.G, Twenty-Five Years: 1892-1916 (New York, USA: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1925), 2:100. xxiii Woodrow Wilson, "Address Before the Southern Commercial Congress in Mobile, Alabama," The American Presidency Project, accessed September 14, 2013, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=65373. xxiv Godfrey Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 87. xxv Edward Mandell House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel House, comp. Charles Seymour (Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1926), 196, 203-205. xxvi Godfrey Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 89. xxvii Edward Mandell House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel House, comp. Charles Seymour (Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1926), 193. xxviii Ibid. xxix House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 206. xxx House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 202. xxxi Godfrey Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 88. xxxii Woodrow Wilson, "Address Before the Southern Commercial Congress in Mobile, Alabama," The American Presidency Project, accessed September 14, 2013, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=65373. xxxiii Godfrey Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 87. xxxiv Grey, Twenty-Five Years: 1892-1916, 2:97. xxxv Edward Mandell House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel House, comp. Charles Seymour (Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1926), 208. xxxvi Ibid, 218. xxxvii Ibid, 207. xxxviii Ibid, 208. xxxix Edward Mandell House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel House, comp. Charles Seymour (Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1926), 210. xl Ibid, 209-210. xli House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 209. xlii House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 213. xliii Ibid. xliv Ibid, 213-214. xlv Ibid, 214-218. xlvi xlvii House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 211. Ibid. xlviii xlix l Grey, Twenty-Five Years: 1892-1916, 2:94-99. House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 195. House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 201. li House, The Intimate Papers of Colonel, 206. lii Butts, "An Architect of the American," 58. liii Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand, 53. liv Ibid. lv Foglesong, America's Secret War Against, 15. lvi Williams, The Tragedy of American, 70. lvii William Appleman Williams, The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, new edition ed. (New York: W.W Norton and Company, 1972), [Page #]; Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand, 87. lviii Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand, 88. Bibliography Benbow, Mark E. “Intelligence in Another Era: All the Brains I Can Borrow: Woodrow Wilson and Intelligence Gathering in Mexico, 1913-15.” Central Intelligence Agency: Center for the Study of Intelligence. Accessed September 14, 2013. https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csistudies/studies/vol51no4/intelligence-in-another-era.html. Bobbitt, Philip. The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace, and the Course of History. New York: Anchor Books, 2003. Butts, Robert H. “An Architect of the American Century: Colonel Edward M. House and the Modernization of United States Diplomacy.” PhD diss., Texas Christian University, 2010. Accessed June 4, 2013. ProQuest (UMI No. 3443311). Cooper, John Milton. The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt. Cambridge, MA: Bleknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1983. Dawley, Alan. Changing the World: American Progressives in War and Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003. Ferrell, Robert H. Woodrow WIlson and World War I, 1917-1921. Edited by Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris. New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1985. Foglesong, David S. America’s Secret War Against Bolshevism. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1995. George, Alexander L., and Juliette L. George. Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House: A Personality Study. Dover ed. New York: Dover Publications, 1964. First published 1956 by John Day Company. Grey, Edward, K.G. Twenty-Five Years: 1892-1916. Vol. 2. New York, USA: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1925. Hodgson, Godfrey. Woodrow Wilson’s Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008. House, Edward Mandell. The Intimate Papers of Colonel House. Compiled by Charles Seymour. Cambridge, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1926. Howard, Michael. War and the Liberal Conscience. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1978. Howden Smith, Arthur D. “Mr. Smith’s ‘The Real Colonel House.’” The New York Times (New York), June 23, 1918. Accessed September 14, 2013. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10615FD3C5A11738DDDAA0A94DE 405B888DF1D3. Karp, Walter. The Politics of War. New York: Franklin Square Press, 2003. First published 1979 by Harper and Row, Publishers. Traxel, David. Crusader Nation: The United States in Peace and the Great War, 1898-1920. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. Viereck, George Sylvester. The Strangest Friendship in History: Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House. 1976. Reprint, Praeger, 1976. Williams, William Appleman. The Tragedy of American Diplomacy. New Edition ed. New York: W.W Norton and Company, 1972. Wilson, Woodrow. “Address Before the Southern Commercial Congress in Mobile, Alabama.” The American Presidency Project. Accessed September 14, 2013. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=65373.