Full Outline - Consid, SOF, Parole

advertisement

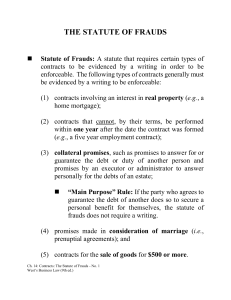

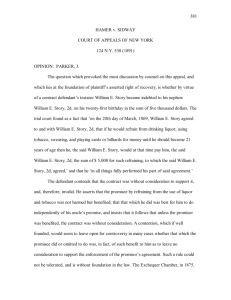

The Three Great Theoretical Oddities of Common Law Contracts Having essentially completed our main focus, namely, the practical aspects of contracts such as negotiation, interpretation, drafting, and trouble-shooting contract problems, the last lecture will take a look at the three great “Common Law Oddities” of contract theory. To those who did not take my introduction class (or do not read about contract law for pleasure) this will be new, and hopefully interesting. For those of you who were in the introduction K class, it will go into these theoretical areas in more depth, and thus should also prove enlightening! I. Common Law Requirement of Consideration: A. In the Common Law system, three initial steps must be made in order for a contact to be formed: offer, acceptance, and consideration. B. CONSIDERATION: This third element is unique to the Common Law. Consideration is a legal concept which requires something of ‘value’ to be exchanged between the parties before a valid contract is formed. Therefore, a contract cannot exist without “consideration” being given by both sides. 1. Consideration can be money, goods, a promise to do something, or anything else that changes the legal position (‘burdens’) the promisor. 2. It is often referred to by the Latin phrase quid pro quo (something for something) i. Restatement §71: Requirement of Exchange; Types of Exchange (a) To constitute consideration, a performance or a return promise must be bargained for. (b) A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise. (c) The performance may consist of (1) an act other than a promise (2) a forbearance (3) the creation, modification, or destruction of a legal relation. 1 (d) The performance or return promise may be given to the promisor or to some other person. It may be given by the promisee or by some other person. ii. Restatement §79: Adequacy of Consideration; Mutuality of Obligation (a) If the requirement of consideration is met, there is no additional requirement of (1) a gain, advantage, or benefit to the promisor or a loss, disadvantage, or detriment to the promisee (2) equivalence in the values exchanged; (3) "mutuality of obligation." 3. The following are NOT CONSIDERED ‘consideration’: a. An illusory promise – one which the promisor actually has no obligation to keep, does not count as consideration. b. Past consideration is not valid – something that is already done is done, and does not change the legal positions of the promisor. Any goods or services to be exchange must be exchanged at or after the time of the contract formation. c. Pre-existing duty - A pre-existing duty does not count as consideration. 4. Situations when consideration does not apply or is modified: 1. Donative Promises = Illusionary Promise: a. In general, a promise to give a gift in the future is unenforceable. b. Pure gift: i. Dougherty v. Salt (1919): Aunt writes note promising nephew $3000 at her death. Court held that there was no 2 contract as there was no consideration. P gave up nothing - there was no condition. Intent of grantor is not enforceable. c. Demand of specific conduct: i. Hamer v. Sidway (1891): promise of $5,000 to quit drinking and smoking. ii. Court held that forbearing from exercising a legal right constitutes a consider action and thus creates a binding contract. d. Reliance on a Promised Gift: i. Ricketts v. Scothorn (1898): promise by grandfather to give granddaughter a demand note for $2000 to allow her to quit her miserable job if she chose. Daughter quit job. ii. Court held that if donee, in reasonable reliance on the gift, incurs debt, expense or significant change in condition, donor may be estopped from revoking the promise on grounds of lack of consideration. 2. Promissory estoppel: a. Restatement §90: a promise expected by promisor to cause promisee to take or forbear some action, and induces such action, is 3 enforceable if necessary to avoid injustice. Remedy may be limited as justice requires. 3. Pure promise without consideration: a. Baehr v. Penn-O-Tex Oil Corp. (1960): P was owed money by a third party. Third party claimed that D had all of its assets tied up. P contacted D, seeking its money. D said they would see to it that P got money. Court held that this was not enough to constitute consideration, despite P’s assertion that he delaying legal action in exchange for the promise. 4. Illusory Promise: a. Definition: a promise that does not bind promisor to any affirmative action or forbearance and thus is not a consideration. b. Promise must be made and executed in “good faith.” i. Mattei v. Hopper (1958): 1. Developer agreed to buy land w/in 120 days subject to obtaining satisfactory leases for projected shopping center. 2. Court held that a “good faith” effort to obtain satisfactory leases was a promise (non-illusory) and thus was sufficient to create a contract. 5. Moral obligations and Past Consideration: 4 a. Webb v. McGowin (1935): promisor saved by employee who was hurt in process of saving him, promised $15 per two weeks for life. Court held that past consideration sufficed. b. Standard: a promise maybe upheld based on past consideration if the promisor himself received a personal benefit for which promisee could justly demand compensation. c. Restatement §86: a promise made in recognition of a benefit previously received is binding to the extent necessary to avoid injustice, unless the benefit was a gift or for other reasons the promisor was not unjustly enriched. 6. Pre-existing Duty – If a party does or promises to do what she is already legally obligated to do, or forbears or promises to forbear from doing something which she is not legally entitled to do, she has not incurred the kind of “detriment” necessary for consideration. a. Construction Contracts – demands for more money in the face of threatened walk-out not consideration. b. Rewards or Bonuses – police cannot collect rewards c. Liquidated debt – a payment which is fixed and undisputed, cannot be negotiated for consideration. - agreement to take partial payment for outstanding debt not consideration. 5 II. The Statute of Frauds and Contract Law A. What Is the Statute of Frauds? 1. The "statute of frauds" - also commonly abbreviated as "SOF" was passed in 1677 in order to prevent wrongful K claims. While contracts normally do not have to be in writing to be legally binding, the SOF requires that certain types of contracts must be in writing and signed by both parties in order to be valid. B. The Purpose of the Statute of Frauds As suggested by its name, a statute was created to assist society in preventing injury from fraudulent conduct. Written agreements with signatures provide greater assurances of the terms of the deal between parties including providing evidence that both parties agreed that a deal was made. This requirement is intended to reduce the chances of litigation, create clarity of the agreement, and also provides people with the opportunity to look the terms and conditions over one last time before making the contract final. C. What Types of contracts are Governed by a Statute of Frauds Over time, certain types of contracts were identified as being the most susceptible to fraud and frequently being of greater importance and dollar value. While the exact requirements vary between jurisdictions, the following represents the most common areas where a Statute of Frauds typically applies. D. You can remember these areas with the pneumonic "MY LEGS" – - Marriage – A promise for which the consideration is marriage or a promise of marriage is within the statute of frauds. While unusual, we've all heard claims that "he promised that if I married him he would buy me a house on the beach." Unless that agreement was in writing, it's not enforceable. Example: A offers to marry B. To induce B to accept the offer, A orally promises to transfer certain stocks to B. B accepts the offer, but changes her mind prior to the actual ceremony. Both promises to marry, and A’s promise to transfer the stocks, are all within the Statute of frauds and therefore unenforceable because oral. Exception: 1. If the oral K solely of mutual promise to marry (with no other “side agreement” to transfer property). 6 - Year - An agreement that, according to its terms, cannot be performed and completed within one year, it must be in writing. Example: Boss and Employee agree that Employee will work for Boss for a 2-year period beginning that day, the K terminable by either side only for cause. Violates SOF. Scope: 1. Time runs from the making of the K date, not the time it will take the party to perform 2. Performance must be impossible within the 1 year period a. Lifetime Employment ? – OK b. Employment for a fixed term ? – violates – can die, but K requires a specific time of performance (K primary purpose not fulfilled. Death = discharge, not performance) c. Covenant not to compete – OK, death seen as “full performance” (no more competition!) d. Support to child (beyond legal duty) - example: pay for child until 21 – OK – child could die within a year. - Land – A promise to transfer an interest in land must be in writing. Example: Mike, the owner of Blackacre, says to Tony, “I’ll sell Blackacre to you for $100,000 to be paid in cash within 30 days from today. Tony says, “Great, we have a deal!” and they both “shake on it” = both not bound by the agreement and neither can sue for it to be enforced. Scope: 1. Applies to all property interests (leases [more than one year by statute], mortgages, easements) Exceptions: 1. full performance by vendor 2. by virtue of significant reliance by the vendee - Executors - Any promise to pay an estate's debts from the executor's private funds must be in writing. A promise to pay the estate's debts out of the estate funds can be oral. - Goods = Sales of goods of $500 or more, now included in the UCC. Exceptions: 1. One sale verses several? – depends on whether the court determines the parties meant a single K, or several individual Ks. 7 2. Contracts combining service and goods? – Where the K is primarily for the provision of services, but also includes provisions for goods, the K is not covered by the UCC, and standard SOF rules apply. 3. What about modifications? A $700 contract that has been modified down to $400 can be oral. A $400 contract modified to $700 is governed by the Statute of Frauds and must be in writing. - Suretyship: A promise or contract to pay the debt of another is governed by the Statute of Frauds and must be in writing. Both evidentiary and preventing/guarding people against hasty oral promises they might later regret! E. Requirements of the Statute of Frauds Typically the statute requires several elements in order to be considered a valid and binding agreement. The writing must: (1) identify the contracting parties (2) recite the subject matter of the contract so it can be reasonably understood (3)provide the essential terms and conditions of the agreement.(4) signatures of both parties. The Uniform Commercial Code states for a sale of good, only the "party to be charged" (the party against whom the contract is sought to be enforced) is required to sign. The party seeking enforcement is conceding the validity of the written contract. In addition, the quantity of goods must also be specified, e.g. 500 bottles of beer and not just "$500 for beer". F. The Application and Effect of the Statute of Frauds The Statute of Frauds makes an agreement that does not comply cancelable or "voidable" by one of the parties pleading the Statute of Frauds. It does not make the contract "void" contract or unable to be enforced, e.g. an illegal contract for the sale of drugs. In addition, both parties can agree that a valid contract exists in court and that it can be enforced. G. Exceptions to the Statue of Frauds. There are times when a party to a contract that would otherwise be invalid under the Statute of Frauds will be able to enforce it. To remember these circumstances, use the "SWAP" pneumonic. 8 - Specially manufactured goods - Goods that have been manufactured per order and can be identifiable to the order. Example: Don orally orders the 50 motorcycles that Ted has on his lot and wants them modified and custom detailed to say "Don's Delivery Service." Ted finishes 10 of them and then Don tries to cancel the deal. In this instance, since the contract calls for specifically manufactured goods, it falls within the exceptions to the Statute of Frauds. - Written Merchants Confirmation - A confirmation of an agreement between two merchants (not consumers) is sufficient to satisfy the Statute of Frauds. Merchants will frequently invoice each other pursuant to oral agreements and the law recognizes this. Example: An invoice identifying the goods, quantity and price pursuant to an oral order and stating that the agreement is firm unless canceled within 5 days. - Admissions in Court - A party to be charged can admit that there was an oral agreement and thus making an oral contract enforceable. - Performance or Promissory Estoppel – 1. To the extent that one party has performed, it can remove an agreement from the Statute of Frauds. Example, Don orally agrees to deliver Ted 200 iPods in exchange for $3,000. Don delivers 100 of them after which Ted challenges the agreement. There is an enforceable agreement for 100 iPodsalthough not for the full 200. 2. The doctrine of "promissory estoppel" – as we know by know, PE is sometimes used when there is a significant inequity that exists that would result in a conclusion that society would deem unacceptable. Example, Don promises Ted $600 to paint his house. Ted told Don that he was going out to buy the paint later that day and Don gives Ted a ride to the store. A week later Don claims there was no agreement since it was oral and thus unenforceable under the Statute of Frauds. In this instance, Don cannot claim ignorance of the agreement and he induced Ted to spend $200 worth of paint. He could have easily avoided Ted's significant expense in time and buying paint. The concept of "fundamental fairness" or promissory estoppel kicks in and will otherwise allow Ted to recover the cost of his efforts. To qualify as promissory estoppel, typically all of the following elements are required: 1. A clear and definite offer was made (offer $600 to paint the house) 2. There was a reasonable expectation of reliance on the offer (Don reasonably expected Ted to rely upon the offer, it wasn't said in jest) 9 3. There existed reasonable reliance on the offer by the party receiving the offer (in our example, Don's promise to pay$600 to paint the house) 4. There was detrimental reliance on the offer (Ted's spending $200 on paint) III: Common Law Oddity, the “Parole Evidence Rule”: 1. Definition: makes unenforceable any oral agreements entered into prior to adoption of the written contract. 2. Restatement §213: a written agreement that is in itself “completely integrated” effectively discharges any prior agreement in its scope. 3. The varying case law: a. Mitchill v. Lath (1928): oral agreement to remove ice house as part of sale of land was barred under parole evidence as the contract was held to be completely integrated. To be enforced: i. Must be collateral in form (capable of being a separate agreement) and does not contradict terms of written, and ii. Written contract fails to fully integrate. iii. Rule: prior oral agreements only enforceable if it has separate consideration. b. Thompson v. Libby (1885): Classical approach to Parol Evidence Rule. P and D contract for logs. P sues to get payment. D claims there was a verbal warranty for the quality of the logs. Court says that if contract is complete as written court will assume that was all parties intended. 10 Collateral exception will not help here because a warranty is a material, not collateral, term of sale. c. Masterson v. Sine (1968): Court allowed parole evidence that contract included a “non-assign ability” clause with regards to right to repurchase property w/in 10 years. i. If evidence of prior agreement was credible, then written contract could not be considered fully integrated. d. Taylor v. State Farm Insurance (1993): P sues D for bad faith in their defense of him after a three vehicle accident. D settled case on behalf of P for $2 million in excess of his insurance policy. P wants to introduce parole evidence to clarify something his attorney did. Court takes the Corbin view--the judge should look at a contract and the parole evidence rule to determine if text is clear. If the text alone is clear, fact-finder does not get parole evidence. 4. Current trend: a. Masterson is the majority approach. b. Explicit merger clauses have become more common. c. “True intent” is touchstone for court. d. UCC and Restatements state that parole rule will not bar evidence of trade usage or prior course of dealings. Both may be used to explain or supplement written contract, but may not contradict express written conditions. See Columbia Nitrogen (1971): Court upheld 11 admissibility of trade usage to establish right to renegotiate contract where precipitous change in price of phosphate occurred. 5. No application to oral agreements made after contract. Some Problems, What do you think ? 1. George Washington’s friend Benny Arnold, tells him, “If you walk across the street with me now and go into the hardware store, I’ll buy you an axe.” Washington crosses the street and enters the store. Arnold reneges. Has Arnold breached the K? 2. ABC Bakery has a contract with Marie Antoinette to deliver 1,000 cakes for a Bastille Day Party Antoinette is hosting. ABC Bakery fails to deliver, and Antoinette threatens to sue. ABC says, “If you agree not to sue, I’ll give you a strand of black pearls.” Antoinette agrees, and accepts the pearls. Is the agreement enforceable? 3. The New World Cruise Company hires Christopher Columbus to perform a publicity stunt for them – Columbus promises to sail due West to discover new lands, in return for which NWCC promises to pay 500 barrels of wine on completion. Just before Columbus sets sail, he decided that the payment isn’t big enough, and refuses to go unless NWCC “ups the ante”. NWCC says, “OK, we’ll also name a town after you if you are successful.” Columbus agrees sails, discovers America, and collects 500 barrels of wine; however, NWCC refuses to name a city after him. Under the Common Law principles, can Columbus enforce the capital-naming promise? 4. Lear agrees to lease his castle to Richard for nine months, with the lease to begin in six months from the signing of the K. a. Must the lease be in writing under the Statute of Frauds? b. Say instead that the lease is to begin immediately, and to last for nine months. Must the lease be in writing? 5. Charlie Tuna orally agrees to supply Chicken of the Sea with all the fish bait she requires over the next 18 months. Charley fully performs his side of the agreement, but Chicken of the Sea fails to pay up. Charlie sues. Chicken of the Sea defends by arguing that the K is unenforceable because it falls within the one-year provision of the Statute of Frauds. Who wins? 12 6. Washington and Adams agree for Adams to sell Washington 1000 Declaration of Independence Commemorative Placemats, which Washington intends to re-sell. They sign a written K, which both parties intend to represent all aspects of their agreement, and which both parties intend to be final. One day after the writing is signed; the parties orally agree that the price to Washington will be adjusted from $.40 to $.30 apiece. Adam then ships the mats, with an invoice showing $.40 apiece. If Washington refuses, and Adam sues, may Washington prove in court that the oral modification occurred? 13