ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF

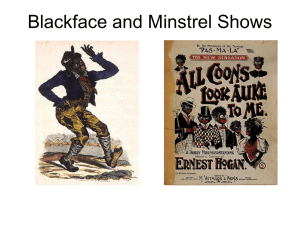

advertisement