1 Handel and Musical Borrowing Throughout the history of the

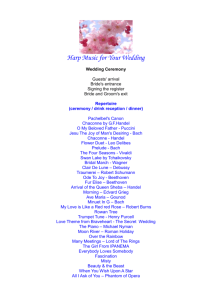

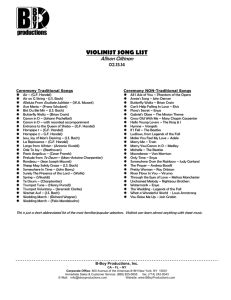

advertisement