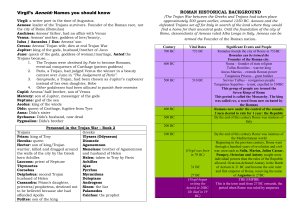

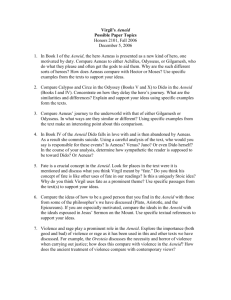

Virgil's Aeneid: A Discussion Guide

advertisement