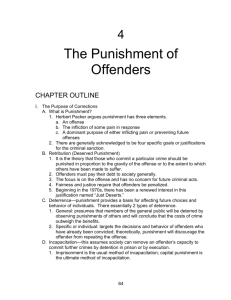

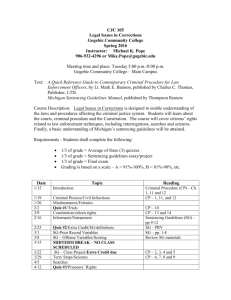

CriminalProsecutions..

advertisement