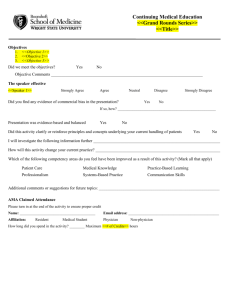

CULTURAL AWARENESS SENSITIVITY TRAINING

advertisement