A ROSARY FOR OUR LADY OF THE MAGMA

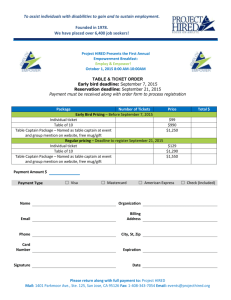

advertisement

A ROSARY FOR OUR LADY OF THE MAGMA When the wind gathered force, the ship’s timbers shrieked like the voices of the children who had burned in the xenodochium. Modester Kline huddled in his cabin watching the hull flex. Seasickness crept up on him like the war had done, at first annoying and then consuming his entire world. He clung to the bucket they’d presciently given him and vomited up everything he’d eaten since they set sail. Even after his stomach was empty the nausea did not subside. He cherished it. Feeling sick was better than thinking about the past. Presently the captain came in. He eyed with disgust the vomit that Modester had deliberately spilled from the bucket. “I’d have you lick that clean, lubber. But I’ve other uses for you. Up.” “You’ll have to unchain me first.” Modester, who had once worn scapular chains symbolizing his vows, now wore a chain on his ankle. It was attached to a ring in the roof of the cabin normally used for hanging a hammock. He had thought about trying to hang himself with it, but he was afraid of meeting the children. The captain unlocked the chain from the ring, but not from Modester’s ankle. He draped the long end around Modester’s neck, causing him to stagger under its weight, and laughed loudly. “There’s your new scapular, friar!” That was the kind of prank these Aloiester donkeys thought funny. Up the ladder Modester climbed, the chain clanking and his cassock hampering his legs. It was the same cassock he’d been wearing the night the Duke of Aloieste’s men came, almost a year ago. At this point it could have stood up on its own better than he could stand up in it, especially since the deck yawed drunkenly. He’d assumed that because the captain had come to his cabin, the storm must be over, but still the sea heaved and surged. And still the timbers creaked and the rigging shrieked. He had merely gotten used to it. “See anything?” the captain bellowed. The ship rolled, and Modester fell down. Some of the sailors picked him up, pissing themselves laughing. “I see nothing but a crew of murderers,” Modester said. The worst of it was that Aloieste lay as close to his own homeland, the Duchy of Trigauldon, as thumb to fingers. Until the war broke out he used to ride to market in Aloieste every week atop a cart laden high with casks of water from the monastery’s holy spring. Got a fair price from the Aloiesters as a rule, too. The captain hit him. “Aren’t you friars meant to seek the good in every man and God’s hand in everything? But, the hell with that. We didn’t spare you to give us compliments. We spared you to give us land. So where is it, monk? Show us what you can do!” Modester wiped blood out of his beard. “I’ll need my dowsing rod.” In truth, he didn’t need it. He was not a sorceror, to wave a magic wand and utter curses. Dowsing was a gift, not an art. But sorcery was what people considered worth paying for, and so the Order of Diviners had approved the use of dowsing rods. Modester hoped the Aloiesters had not brought his rod on this voyage. Then they might decide he was no use to them. The sea beckoned, grey and ghastly. They put into his hands the gold-plated dowsing rod that had belonged to the abbot of Our Lady of the Magma. Modester fingered the brightly colored enamel figurines of the Lady atop the rod, remembering how the Aloiesters had cut the abbot down on the threshold of the chapel. An unarmed old man. With his last breath the abbot had pleaded with them to spare the children. He threw himself at the captain. Sheer astonishment delayed the man’s reaction long enough for Modester to close the distance—despite the chain dragging behind him—and stab the long end of the dowsing rod into the captain’s unshaven throat. Modester was the bigger man. He bore down, using his body weight in a way he had not done since he was a novice brawling in the scriptorium. The rod broke the skin. He was dowsing, dowsing for blood. He ground the rod into the gristly resistance of the larynx. They broke his arms and legs first, then all the little bones in his hands. Then his feet. He repeatedly fainted and they brought him around by pouring strong grog down his throat. Taunting him to call on his Lady for help, they slashed open his abdomen and pulled out his entrails, then draped those around his neck like chains. They never got tired of their own stupid jokes, the murderers. Sunlight on his face woke him. The porthole framed a perfect circle of blue sky. The sea, false friend, slapped the hull in a gentle rhythm. Modester stretched as far as the narrow cabin would allow. Something rolled out from between his arm and torso. When he sat up, another object fell out from under his cassock. With a pang of recognition, he collected the filigreed silver feretories. After torturing him, the Aloiester knaves had healed him with saints’ relics that belonged to Our Lady of the Magma. Puissant and indifferent to earthly circumstances, the saints would have done the same for anyone. They did not distinguish between good men and sinners. But for the first time since he was taken captive, Modester felt a traitorous desire to live. The captain, too, had been healed overnight of his wound, but he still spoke with a noticeable rasp. “We’ll have no more dirty tricks from you, friar, or the next time will be the last.” A large sailor stood by with a cutlass. The captain, sitting in a comfortable chair on the aft deck ,gestured towards the horizon. The sea was now so placid that Modester could see the grey backs of dolphins breaking the surface. “These are unclaimed waters. Somewhere over there is Gyre. South, Zinlandic waters; north, the Ur; home is back that way. As you may know, maritime law allows sovereigns to claim territorial rights up to ten leagues from their nearest possessions. Gyre’s got the Shaftmount Isles, and that gives her a big bulge of territorial waters where her freebooters may lurk and jump out at us on our way along the coast. Then they skedaddle back to the Isles and claim they were just out fishing. Yes, fishing for Duchies cogs with their holds full of trade goods! It’s blatant piracy. As a Duchies man yourself, you ought to be as infuriated about it as I am.” “I was born in the Duchy of Trigauldon but my allegiance is not to any earthly sovereign. I am sworn to the Kingdom of Heaven.” “Yes, and that’s the trouble with you God-botherers. Bloody traitors in our midst. Parasites; sorcerors.” The captain swigged from a leathern flask and calmed down. “Anyway, the Duke has had a clever notion. If we had our own islands—somewhere right around here—then we, too, could claim territorial waters extending far beyond our shores. Station a couple of warships there, and the Gyrish would think twice before raiding our merchantmen. Perhaps we could even do some raiding of our own. Isn’t that a beautiful thought?” Modester gazed at the ocean. He said, “You seem much concerned with the niceties of maritime law. Yet your army disregarded every law of heaven and earth on the night you burned Our Lady of the Magma, and all the children of the town—” he forced himself to speak calmly— “in the xenodochium, where their parents had sent them to take refuge, believing we would keep them safe.” “That’s different,” the captain said. Modester shuffled his bare feet, making his shackles clank. Today they had chained his ankles together. From years of going barefoot in all weathers, he had developed horny soles impervious to heat or cold, but the healing of his shattered feet had also dissolved the calluses, leaving his soles as pink as a baby’s. The deck was hot from the sunlight; it burned his feet. “I see no islands,” he said. “Porridge for brains,” the captain snarled. “That’s why you’re here. To dowse for them. They’re down there somewhere. Plumes of smoke have been spotted.” “And if I were to find these islands of yours, what then?” “You bring them up. You are a sorceror, aren’t you?”