The Funny Thing about Trees

advertisement

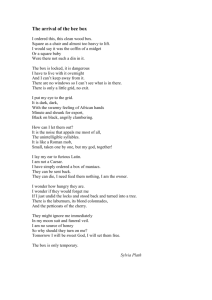

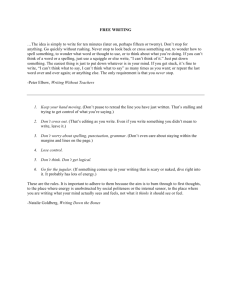

The Funny Thing about Trees M AT T H E W B E VIS Fig. 1. Tombstones for Sale by Elizabeth Bishop. Reproduced with permission from Susannah Hunnewell Weiss. E lizabeth Bishop’s Tombstones for Sale (fig. 1) hangs above my desk, and I look at it most days without quite knowing what I’m looking at. It seems to contain—and to encourage—a sense of humor as well as a sense of wonder. Behind the astonishing tree, manmade objects dutifully line up to stake their claims for Man. Tombstones to the left, flowerpots to the right, and in each group the central figure makes a bid to be “special” (a large cross here, a dash of blue paint there). Yet the objects’ effort to stand out from the crowd feels ruefully comic, especially given that the tree steals the show. “For sale” also has a kind of dark wit; the sign is a reminder that one person’s death keeps another person in business. And the words on the gravestones may also be a joke about epitaphs (even though epitaphs are 86 m at th e w b ev is u 87 meant to be tailored to the individual, they often sound the same; you could say they tell the same story). What I can’t figure out, though, is the relationship—if it is a relationship—between the headstones and the tree. The objects could be putting death in its place by warning against sentimentality (“Somebody’s got to make a living, and other things will go on living regardless”). Or perhaps they conspire to create a memento mori (“You’ll soon be pushing up daisies, or trees, so be sure to enjoy the moment”). But these translations make it sound as though the picture is trying to teach something, which doesn’t feel exactly right either. The tree may invite wonder, but it’s not proselytizing, and it’s not overly concerned by what I make of it. Looking at it again brings to mind a line from one of Bishop’s poems: “all the trees laughed at some joke.” I’m not sure I get it. Maybe I’m the joke. People captivated by objects of wonder often become objects of laughter. Nigel Molesworth—the schoolboy narrator of Geoffrey Willans’s Molesworth stories—has much fun at the expense of the school sissy, Fotherington-Thomas; the hapless boy is mocked on the football pitch for being wonder-struck when he should be paying attention to the game: “It is a funy thing,” Molesworth notes, “fotherington-tomas skips about when he is golie ‘Hullo trees Hullo birds.’ ect. He luv only bountiful nature.” The defenders on the goalie’s team are not impressed, and it would appear that the modern age is running out of defenders of wonder more generally. “Small wonder,” “no wonder”: the phrases point to diminishing returns. If somebody says that “wonders will never cease,” they usually wish it to be known that wonder has ceased. But this skepticism isn’t a recent development. There have always been naysayers who have dismissed wonder as nostalgic or naive or just plain silly. On occasion, even those caught up in wonder have been caught in two minds about their high spirits. In Shakespeare’s As You Like It, Orlando proclaims his love for Rosalind by inscribing poems to her onto the bark of trees in the forest of Arden. Rosalind learns about this just before her maid, Celia, arrives and asks: “But didst thou hear, without wondering, how thy name should be hanged and carved upon these trees?” “I was seven 88 u rar ita n of the nine days out of wonder before you came,” the heroine replies. She’s drawing on John Heywood’s Proverbs—“A wonder lasteth but nine days”—and so admitting that she’s feeling wonder while also feeling a little embarrassed about it. In a couple of days, she implies, she’ll be in her right mind again. From Plato’s Theaetetus onward, many accounts of wonder have emphasized a similar point: the feeling is temporary. Not temporary in the sense that all good things must come to an end, but in the sense that the phenomenon is a short-lived aberration. Wonder has been seen as another name for error or ignorance. To wonder is to blunder. Once the source of confusion has been properly investigated and accounted for, the feeling will evaporate. As Hymen later says in As You Like It: “Feed yourselves with questioning; / That reason wonder may diminish.” From this perspective, those who continue to dwell in wonder are just not asking the right questions. Yet Hymen’s statement is tricky; the phrase “reason wonder may diminish” is ambiguous and could suggest that wonder may diminish reason: the more questions that are raised, the more the rich strangeness of an object or a situation can make itself felt. So wonder needn’t be unreason, exactly, but a sharpened sense of the limits of the reasonable. Celia is having none of it. When Rosalind wonderingly asks her how the trees came to be so engraved, Celia can’t resist teasing her: “O wonderful, wonderful, and most wonderful wonderful, and yet again wonderful, and after that out of all hooping!” But Celia doesn’t have the last laugh. Rosalind’s capacity to feel wonder, and to make others feel it, is a vital source of the play’s power. Wonder is an emotion that some people don’t want to give up on, so is it possible to think about wonder without becoming either too sentimental or too skeptical—that is, without turning into either the undoubting Fotherington-Thomas or the redoubtable Celia? The feeling may be dismissed as laughable, yet its possible connections with the laughable may shed new light on the strange value of the feeling. Wonder is often exhilarating, and “exhilaration” and “hilarious” share the same root (from the Latin hilaris, meaning cheerful). To find out what might grow from this root, I want to stop and stare at an object m at th e w b ev is u 89 that everyone has encountered. My plan is to stare at it until it turns funny or wondrous or neither. I could easily have chosen something else, and a tree isn’t immediately promising as an object of comedy or of wonder (many would say that bananas are funnier, and mountains more awe inspiring). Nonetheless, a tree seems to me as good an object as any to think with. This essay is primarily interested in wonder as a kind of flirtation with knowledge as well as a deferral of it, so I won’t be explicitly declaring my own argument and intentions until later on. I’m emboldened by an exchange in Richard Jefferies’s novel, Bevis: The Story of a Boy. My namesake is playing truant in the woods: “‘What be you doing to that tree?’ said the Bailiff. ‘Find out,’ said Bevis. ‘It’s not your tree.’” u u u So she went on, wondering more and more at every step, as everything turned into a tree the moment she came up to it. —Lewis Carroll, Alice Through the Looking-Glass When I was around Alice’s age, my older cousin Saul amused himself by taking my unbreakable magic stick and thwacking it repeatedly against my favorite tree in our back garden. It eventually snapped in two. I took it personally, but I also remember feeling that he’d somehow injured or distressed the tree by using it to inflict damage on one of its own limbs. My intense dislike of Saul since then has become a family joke, and my family has not found the thing any less funny when I have claimed that trees are no laughing matter. In The Iliad, they are a reminder of life’s evanescence (“Men come and go as leaves year by year upon the trees”) and in classical myths they often spring up when the situation is getting desperate (Daphne escapes Apollo’s clutches by being turned into a laurel tree). Shel Silverstein’s children’s book The Giving Tree has been given many times in recent years, and the tree has generally been read not as a comedian, but as a guide or loving parent or earnest friend or any other number of solemn, sage-like figures. 90 u rar ita n Trees, it would appear, demand to be taken seriously. Old Germanic tribes meted out severe punishment to anybody who dared to peel the bark from a standing tree; the malefactor’s navel was cut out and nailed to the spot where the bark had been, and he was then driven round and round the tree until his guts were strung out across its trunk. Arboreal shadows darken the Christian story too; the Tree of Knowledge portends trouble in paradise, and in the New Testament the Greek term used to refer to the cross is xylon (ξύλον), which can mean either a live tree or an object constructed of wood. The painter and writer David Jones asks, “If the poet writes ‘wood,’ what are the chances that the Wood of the Cross will be evoked?” The chances are perhaps greater once the question has been put like that (maybe Jones thinks that the tree/cross that Jesus climbs is a site of wondrous paradox, and so greater than the tree with the apple of knowledge). In Virgil’s Aeneid, a bleeding, talking tree elicits fearful awe; in the dark wood of Dante’s Inferno, talking trees are imbued with the spirits of those who have committed suicide; and in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the arrival of Birnam wood at Dunsinane is the herald of fearful wonder. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud’s astonishment at the uncannily repetitive nature of erotic wounding is heightened by a tree in Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata: The hero Tancred unwittingly kills his beloved Clorinda, she having done battle with him in the armor of an enemy knight. After her burial he penetrates the strange charmed forest that so frightens the army of crusaders. There he smites a tall tree with his sword, but blood gushes from the wound, and the voice of Clorinda, whose spirit has magically entered into that very tree, accuses him of yet again doing harm to his beloved. Some etymologists claim that the roots of wonder come from the German word for “cut, gash, wound.” And here, “yet again,” a wondrous tree is about as far from the comic as could be imagined; to penetrate strange forests—or to penetrate trees with swords—is to come into contact with the fear lurking inside desire, a fear that you are doomed to keep reliving. From the Judas Tree to the Tyburn Tree m at th e w b ev is u 91 and beyond, the landscape of wondrous trees does initially appear to be a pretty grim one. When, in Milton’s Paradise Lost, Satan boasts to his crew that he’s helped to bring about the fall of man, he does briefly move from talk of wonder to talk of laughter: “Him by fraud I have seduced / From his Creator; and, the more to increase / Your wonder, with an apple; he, thereat / Offended, worth your laughter!” The joke, however, is not one that fallen mortals are likely to enjoy. What grows on trees? Weighty thinking. Plato’s philosophizing took place under the shadow of Socrates’s plane tree. Another tree helped to accentuate the gravity of Isaac Newton’s thoughts, and another enabled George Berkeley to ponder the mind’s relationship with the world; in his Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, Berkeley asks whether “trees, for instance, in a park. .. with nobody by to perceive them,” can really exist. When inquiring minds have perceived them, trees have become metaphors for the structure of human knowledge and for mankind’s place in the world —from Linnean classification systems, via Charles Darwin’s “Tree of Life” in Origin of Species, to the phylogenetic trees of present-day evolutionary biology. In the Origin Darwin notes: The affinities of all the beings...have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent existing species; and those produced during former years may represent the long succession of extinct species. The simile speaks the truth and the truth bespeaks a wonder, as Darwin goes on to point out: “It is a truly wonderful fact—the wonder of which we are apt to overlook from familiarity—that all animals and all plants throughout all time and space should be related to each other.” So our familiarity with something stops us wondering, yet it is the very fact of biological familiarity itself—the familiar, Family Tree of existence—that we should be wondering at. Like Alice, people who are given to “wondering more and more” start to see trees everywhere. As passive yet flourishing life-forms that don’t have a mind of their own, trees seem to attract minds to 92 u rar ita n them; their sheer receptivity becomes an invitation to thought. In Ideas, Husserl turns to a tree in order to set out the task of phenomenology; in What Is Called Thinking?, Heidegger uses another apple tree to work out how to think. Despite—or because of—the prohibition on the Tree of Knowledge, trees keep being dreamt up in order to explore claims about knowledge. (It’s significant that, in Paradise Lost, Eve’s first words to Adam after eating from the tree are: “Hast thou not wondered, Adam. . .?”) Wittgenstein’s own dream wouldn’t have been out of place in Wonderland, or in Eden: I am sitting with a philosopher in the garden; he says again and again, “I know that’s a tree,” pointing to a tree that is near us. Someone else arrives and hears this, and I tell him: “This fellow isn’t insane. We are only doing philosophy.” I’ll be returning to this particular tree to gaze at it from different angles, but for now it’s worth noting that it is not strictly necessary that readers be told the philosophers were “in the garden.” The detail could suggest that this is another Eden of sorts: the fellow might be naming things as Adam did, or trying to know them as Eve did. The decision to zero in on something that appears obvious or trivial or banal (“I know that’s a tree”), and then to put pressure on it until whatever we know—or whatever we think we know—becomes a source of astonished wonderment, might be one version of “doing philosophy.” But what’s even more astonishing is the sense that the state of wonder itself encourages a taste for humor. It’s as though moments like this are tangled up with a feeling that there’s some funny business going on. Just before glancing at the tree in the garden, Wittgenstein observed, “the information ‘That is a tree,’ when no one could doubt it, might be a kind of joke and as such have meaning.” This is the kind of joke in which others have indulged—especially those who delight in turning the mediocre into the memorable. In Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, the audience is faced with “A country road. A tree. Evening”: m at th e w b ev is u 93 vladimir: (Silence. He looks at the tree.) Everything’s dead but the tree. estragon: (Looking at the tree) What is it? vladimir: It’s the tree. Vladimir’s comment could be a platitude that houses a profundity, or maybe the two men are simply talking at cross-purposes; things are both clear and not clear. Wittgenstein remarked that “a good and serious philosophical work could be written that would consist entirely of jokes.” So, if a tree falls on a philosopher in a forest, and nobody is around to hear him scream, is it still funny? More generally: how might a joke help to illuminate the connections between wonder and humor? By “humor” I do not mean Saul the Stick-Slayer’s humor; what tickled him was a relish for exposure, for the shattering of my illusions and the wonder that went with them. The following wonderings will tend to avoid discussion of his particular brand of comedy, although I’m not ruling out the possibility that this avoidance is linked, in some obscure way, to my continued need to believe in whatever it was that made my stick magic. u u u I don’t know why, but I just don’t trust trees. I appreciate that they are supposed to provide oxygen for us, but I’m not entirely sure that I believe that. They intimidate me—probably because I’ll end up dressed in one before long. —Jarvis Cocker Notwithstanding Cocker’s suspicions, there can be a kind of comedy lurking in wondrous trees. To return to Daphne being pursued by Apollo, for example: when the Renaissance painter Antonio Pollaiuolo imagined how she ended up dressed in a tree, he pictured her just so (fig. 2). Eugene Ionesco suggested that “If you want to turn tragedy into comedy, speed it up.” This is what Pollaiuolo does here, and Tom Lubbock was right to sense a joke in the extreme abruptness and incongruousness of the change: “the picture gives no impression of gradual, graceful, organic transformation. The fleeing 94 u rar ita n Fig. 2. Apollo and Daphne by Antonio Pollaiuolo. Copyright by National Gallery, London/Art Resource, NY. nymph raises her arms in alarm and appeal, and they just go whomp! . ..tree!—with a flourish like a conjurer’s bouquet.” It almost looks as though she were flapping her arms to fly, but instead of wings the mischievous gods decided to kit her out with foliage. Lubbock’s fleeting analogy between conjuring and comedy is suggestive, as both activities may create a similar kind of wonder. m at th e w b ev is u 95 One of the most famous tricks created by the father of modern conjuring—the nineteenth-century magician Jean Eugène RobertHoudin—was “The Marvellous Orange Tree,” in which he appeared to make an orange tree sprout blossoms in seconds, followed swiftly by fully grown oranges. The trick was recently redeployed with even more spectacular flourishes in the film The Illusionist, where Eisenheim the illusionist, played by Edward Norton, tells the audience that there are dull days when we all wish “we could speed things up a bit,” and then proceeds to plant an orange pip in a pot onstage, from which a tree grows and bears fruit in a matter of moments. So, when you want to work magic with reality (just as when you want to turn tragedy into comedy), speed it up. Perhaps this is why audience members don’t just gasp, but gaspingly laugh, when the trick reaches its climax. A good trick is like a punch line; it produces something unexpected out of thin air. We knew something was coming, but we’re still left wondering at the delighted disorientation we experience. The Illusionist was based on Steven Millhauser’s short story, “Eisenheim the Illusionist,” which relates rumors of how the hero was converted to a life of magic when he met a man in black sitting under a tree. The man conjures a variety of things from Eisenheim’s ear (coins, roses, flute, billiard ball), before then vanishing along with the tree. In a wry aside, the narrator notes: “Stories, like conjuring tricks, are invented because history is inadequate to our dreams.” So magicians and storytellers are allies. Both groups trade in illusion because they know we want to believe in a world that contains wonder. And comedians are like this too; they conjure with desire. Here’s an old Yugoslav-Bosnian joke about Mujo and Haso. Mujo is describing his adventures in the Sahara: “I’m walking through the desert. Nothing but sand around me, not a living soul, absolutely nothing. The sun burning in the sky, and my throat burning with thirst. Suddenly a lion appears in front of me. What to do, where to hide?—I climb a tree...” “Wait a minute, Mujo, you’ve just told me that there was nothing around but sand, so where did the tree come from?” 96 u rar ita n “My dear Haso, you’d don’t ask such questions when a lion appears. You run away and climb the first tree.” Whomp! Tree! And the tree—like the punch line—is like a rabbit out of a hat. This is a wondrous joke about what we need jokes to do for us. After all, if po-faced Haso is going to be a stickler, he should also ask what the lion is doing there (is a lion any more likely than a tree in an empty desert?). He is wondering in the wrong way—looking for reasons when he should be looking for pleasures. What Mujo teaches is that when the world is turned into a joke, it becomes the best of all possible worlds: a world we can make up as we go along. Wondrous comedians and conjurors are escape artists in flight from the normal. They allow audiences to feel that escape needn’t be denigrated as mere escapism, but celebrated as a form of dextrous opportunism. They encourage us to like surprises—and to be surprised by what we like. Some of the funny trees I’ve been gazing at so far have roots that run deep, and a quick detour through the comic tradition can help to revise the bleak outlook I sketched earlier (those dark trees from Virgil, Tasso, Dante, and others that seemed to portend fearful wonder). Writers have frequently tended comic thoughts by attending to trees. Greek drama was staged in and for the polis, yet it also allowed city dwellers to imagine seductive green spaces elsewhere; in the earliest surviving comedy in the Western canon—Aristophanes’s The Acharnians—the hero is named Dikaiopolis, meaning “Honest Citizen,” or “he of the just city.” But he’s also a farmer: “Oh, Athens, Athens,” he grumbles, “I’m gazing at the countryside over yonder. ..cursing the city and yearning to get back to my village.” The goddess of comedy, Thalia (from the Greek Thaleia, meaning “luxuriant, blooming” and thallos, “green shoot, twig”), presides over an impulse that seeks fruition in some versions of pastoral. The first line of Aristophanes’s Birds says a lot: “Do you think I should walk straight for that tree?” The walk continues in Shakespeare’s comedies. In The Merry Wives of Windsor Falstaff advises, “Be you in the Park, about midnight, at Herne’s oak, and you shall see wonders.” Comedy leads into m at th e w b ev is u 97 woods, where everything is allowed time off from business as usual. “There’s no clock in the forest,” Orlando observes in As You Like It, and shady pleasures are rife as Rosalind cajoles him among the trees: “Come woo me, woo me, for now I am in a holiday humor, and like enough to consent.” A Midsummer Night’s Dream is set near Athens, the birthplace of comedy, “in the wood, a league without the town.” When the young lover Demetrius announces, “And here am I, and wood within this wood,” he means that he is being driven crazy (“wood” from the Old English wód, meaning “raging, frantic”), but also that he is being wooed—just as Orlando was—absorbing the fertile spirit of a place where words, hands, and imaginations are given license to roam. Demetrius was frantic, but he was frantic within a mode that assured audiences he’d be OK in the end. Comedy’s wondrous family tree toys with wretched or tragic associations, before deciding to offer a different take on things. As every child knows, after a long voyage the owl and the pussycat find happiness in “the land where the Bong-Tree grows.” When Edward Lear wrote a prose sequel to his poem, he killed the pussycat at the end, without quite killing her off: “Shortly after muttering these words, she fell off the tree and instantly perspired and became a Copse.” No corpses here; this is the Fall that doesn’t usher death into the world—a perspiring, not an expiring (wood sweats too). Tennyson’s “Amphion” also celebrates the ability of nonsensical, poetic thinking to bend the rules: The poplars, in long order due, With cypress promenaded, The shock-head willows two and two By rivers gallopaded. Came wet-shod alder from the wave, Came yews, a dismal coterie; Each plucked his one foot from the grave, Poussetting with a sloe-tree. Cypresses and yews are no longer associated with mourning, and willows aren’t weeping. Again, the comedy lies in the speeding up; 98 u rar ita n there’s nothing slower than sloe trees, but here they need only a little encouragement to take to the dance floor. Comedy occurs when trees put their best foot forward, when a setting turns into a pousetting. The mode promises a reprieve from reality. To ponder these dendritic delights is to glean something about where the comic might be encountered, but it doesn’t do much more than skirt around the question of why it’s funny, nor does it fully address the issue of how the comic might be seen as a close associate of the wonderful. Woody Allen’s ecstatic conjugations of tree-ness in “On Seeing a Tree in Summer” can help to clarify things: Of all the wonders of nature, a tree in summer is perhaps the most remarkable, with the possible exception of a moose singing “Embraceable You” in spats. Consider the leaves, so green and leafy (if not, something is wrong). Behold how the branches reach up to heaven as if to say, “Though I am only a branch, still I would love to collect Social Security.” And the varieties! Is this tree a spruce or poplar? Or a giant redwood? No, I’m afraid it’s a stately elm, and once again you’ve made an ass of yourself. ...But why is a tree so much more delightful than, say, a babbling brook? Or anything else that babbles, for that matter? Because its glorious presence is mute testimony to an intelligence far greater than any on earth, certainly in the present Administration. As the poet said, “Only God can make a tree”—probably because it’s so hard to figure out how to get the bark on. There have been many theories about what makes people laugh, but three ideas have loomed large in that particular forest. The superiority theory: Thomas Hobbes claimed that “laughter is nothing else but the sudden glory from some sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others” (watching somebody walk into a tree, say, or fall out of one). The incongruity theory: laughter is inspired by contradictory or incongruous ideas coming together (a tree going bowling, or ordering its shopping online). And the relief theory: laughter is a marker—and release—of fear or anxiety (as when the tree that fell on our dearest philosopher m at th e w b ev is u 99 friend turns out to be merely a hypothetical one). All three models can be applied to various aspects of Woody’s thoughts on wood: the superior gibe at the present Administration; the incongruous moose in spats; those leaves, which are—thank God—very leafy. These evergreen explanations have their charm, but something else is transpiring here that is not covered by the theories. It’s harder to codify, but it’s related to Woody’s focus on “the wonders of nature,” his own willingness to make what comes naturally seem wondrous (he may laugh at reverie, but his skit is a kind of reverie too). When thinking about the possible causes of laughter in his Passions of the Soul, Descartes suggested that “the first is the surprise of Wonder. .. when joined to joy.” This again suggests that humor and wonder can be a kind of double act. Both may involve a desire to be surprised by the everyday, or a capacity to appreciate the surrealism of the real. In the passage above, Woody ends by referring to Joyce Kilmer’s lines— ”Poems are made by fools like me, / But only God can make a tree”— and his recourse to what the poet said is fitting because poets, along with comedians and philosophers, are the creatures most prone to risking foolishness in order to dally with the wonderful (Andrew Marvell spoke for both tribes when he proclaimed: “Thus I, easie Philosopher, / Among the Birds and Trees confer”). If only God can make a tree, the fact that the Tree of Knowledge is off-limits isn’t likely to make mortals think less about it, as Byron appreciated. From Don Juan: But these are foolish things to all the wise, And I love wisdom more than she loves me; My tendency is to philosophize On most things, from a tyrant to a tree; But still the spouseless virgin Knowledge flies. What are we? and whence came we? what shall be Our ultimate existence? what’s our present? Are questions answerless, and yet incessant. Talk of “a tyrant” so close to “a tree” obliquely casts aspersions on the heavenly disciplinarian who outlawed the pursuit of certain forms of 100 u rar i ta n knowledge. Writers who are philosophical about things are intrigued by the kind of knowledge that keeps flirting with you and giving you the slip (another name for this alluring encounter could be wonder). Although Byron’s lines speak of being drawn into a series of endless nonconsummations, they don’t sound all that forlorn; there is a delight here too, a comic relish for mankind’s attraction to the incessantly answerless. As he puts it elsewhere in Don Juan: Man’s a phenomenon, one knows not what, And wonderful beyond all wondrous measure. This knowingly unknowing way of seeing things is not really—or not only—felt as a predicament, but also as an energizing pleasure, something akin to Camus’s sense of the absurd in The Myth of Sisyphus, born of the confrontation between a human need to understand things and the recalcitrance of the world to human understanding. “Living,” Camus notes, “is keeping the absurd alive.” Indeed, the absurd is a commitment to a certain style of life: “one does not discover the absurd without being tempted to write a manual of happiness.” Should the manual ever be written, what its author might be tempted to say is that wonder, like its close relation the absurd, acknowledges the maze inside amazement, but without implying that a removal from the maze would always be desirable. Part of what feels funny (sometimes darkly, sometimes lightly funny) about wonder is the feeling that puzzlement may sponsor plenitude. To say more about this absurd state of grace, a few more trees will be required. u u u The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way. —William Blake Keats was adamant that “if Poetry come not as naturally as the Leaves to a tree it had better not come at all,” and trees appear to come naturally to poets. “Treeify,” “treey,” “treeship,” “tree-loving”: m att h ew be vi s u 101 according to the Oxford English Dictionary, these words were invented by poets (James Russell Lowell, Arthur Hugh Clough, William Cowper, and Robert Bridges, respectively). As I noted earlier, from Virgil onward several terrifying trees of wonder have been planted in this poetic arboretum, but there are also many funny specimens, especially in post-Romantic poetry. Wallace Stevens watches “the hilarious trees / Of summer”; Alice Oswald observes “the funny bone of a conifer”; Dannie Abse spots “a buffoon amidst these oaks,” a “funny one” that “exists for funny children.” Some trees—when gazed at, rather than merely glanced at—become not only witty in themselves, but also the cause of wit in others. In W. S. Gilbert’s “Jester James,” the clown and his master turn to one specimen for inspiration: And every morn, from eight to ten, they’d sit beneath a tree, Rehearsing conversations that would lead to repartee .......... ..................................... .. .. .... .. ...... . And sometimes James was told to climb a venerable oak, That he might say, “I’m up a tree”—an irritating joke. But still his audience wore a pleasant smile upon their lips, For they saw the Dawn of Reason in these gruesome little quips. To say “I’m up a tree” is merely to tell the audience what it already knows (like Wittgenstein’s philosopher friend when he asserts: “I know that’s a tree”). And yet, as the OED explains, to be “up a tree,” is to be “entrapped, in an awkward position, in a difficulty or fix,” maybe having been chased up there by a pack of wild animals, and this is exactly how the jester feels about having to make bad jokes in front of a hostile audience in order to secure his livelihood. I suppose Jester James could have developed his punning performance a little. Something like: “If I wasn’t such a sap, if I wasn’t so given to wooden humor, then maybe I wouldn’t feel so stumped; but then again, if only the audience rooted for me a bit more, twigged my plays on words, maybe I could branch out a bit, turn over a new leaf” (and so on). Puns can be irritating jokes, but despite their badness the audience may still sense wisdom in the quips because puns ask audiences to 102 u rar i ta n keep wondering about words, to recall that words—like the worlds they help to define and shape—have a tendency to mean more than one thing. To pun is to imply that nothing is simply itself, and that the apparently straightforward may be hiding something. Puns contain the Dawn of Reason because it is a mark of the reasonable to look at a thing carefully by looking at it again—and to wonder what your looking does to the object of your gaze. When Blake wrote that “A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees,” he was not necessarily implying that the fool had got the wrong end of the stick. Like Jester James, the fool who insists on going on and on about the apparently prosaic object in front of him may actually be on to something. Blake helped Henry Crabb Robinson to feel better about one particular tree that had inspired a foolish, laughable sort of wonder. Robinson confessed: I had been in the habit when reading Wordsworth’s marvellous “Ode” to friends, to omit one or two passages—especially that beginning But there’s a Tree, of many, one, lest I should be rendered ridiculous, being unable to explain precisely what I admired....But with Blake I could fear nothing of the Kind, and it was this very Stanza which threw him almost into an hysterical rapture. It’s not hard to see why Robinson was embarrassed by his own enthusiasm; the poet has already said that it’s “a” tree, so “of many, one” only restates the obvious. But what Robinson is admiring here is Wordsworth’s feeling for how, under certain conditions, the obvious can turn both numinous and nebulous. One reason that wonder can verge on the risible or the hysterical is because inside some forms of wonder there may lie the feeling that you are making too much out of something, even as you sense that the thing is beckoning to you to make something of it (in Wordsworth’s line, “a tree” is also “a Tree”). It’s as though you are engaged in the potentially ludicrous activity of m att h ew be vi s u 103 hallucinating the normal, as though you half-suspected that your mindfulness was merely a cover story for madness. I once heard Peter Porter say to Clive James on the radio that “mysticism, at its very best, is almost a joke.” It’s like Blake’s “almost” hysterical rapture— not exactly a movement from the sublime to the ridiculous, but a cognizance of the ridiculous within the sublime. Exaltation isn’t just an escape from embarrassment, but a catalyst for it, and wonder may allow both feelings freedom to breathe at the same moment. Blake gave Robinson permission to admire something without having to give a definitive reason for that admiration. In that sense, he gave him permission to wonder at the lines just as Wordsworth wondered at the tree, for wonder (admiratio in Latin) is a form of esteem that can’t quite be accounted for; it throws observers into confusion even as they feel convinced that they have touched upon something significant. Emerson, in “The Comic,” conducts a thought experiment that, while it may not get to the bottom of the confusion, can be read as a useful gloss on the strangeness of the Wordsworth passage. It can also bring us closer to understanding why we might want this strangeness in our lives: Separate any part of Nature and attempt to look at it as a whole by itself, and the feeling of the ridiculous begins....it becomes at once comic; no useful, no respectable qualities can rescue it from the ludicrous. So comedy can be felt when you start to see something—as opposed to seeing what it is meant to be for, or what it’s meant to be linked to, or a part of. We laugh at idiosyncrasies, and when viewed in a certain light an object seems the epitome of the idiosyncratic—very much its own thing, sui generis, the odd one out. Such a perception of the object may also bring with it a delighted surprise that the object should simply be there at all, and that we are there to witness it. Intriguingly, what Emerson calls “the feeling of the ridiculous,” others have called “wonder.” Wittgenstein noted that “aesthetically, the miracle (das Wunder) is that the world exists. That what exists does exist. 104 u rar i ta n I wonder at the existence of the world. And I am then inclined to use such phrases as ‘how extraordinary that anything should exist.’” And “anything” includes you. Wonder doesn’t simply “make you feel alive,” as the cliché goes; it makes you feel that to be alive—or even just to be—is a very strange thing to be, and that you are just as wondrous as the next person (or tree). G. K. Chesterton thought of a tree when thinking along similar lines in “A Defense of Nonsense”: So long as we regard a tree as an obvious thing, naturally and reasonably created for a giraffe to eat, we cannot properly wonder at it. It is when we consider it as a prodigious wave of the living soil sprawling up to the skies for no reason in particular that we take off our hats, to the astonishment of the park keeper. The removal of the hat is a nice touch. It’s a mark of respect, perhaps even a recognition that we’re on holy ground (Europeans normally take off their hats in church), yet it’s also a simple greeting, from a time when cap doffing was a more common and less portentous way of acknowledging an acquaintance in the street. So wonder could be the honoring of an object as mysterious, otherworldly, but also the recognition of it as one of us (“Oh, it’s you, old chap! How the devil are you?”). Chesterton’s park keeper is a significant figure too. He can be related to the person who turns up when Wittgenstein’s philosopher friend is going on and on about the tree; he’s the person who has to be assured that “This fellow isn’t insane.” He’s also the man who, in Emerson’s words, is mindful of the need for “respectable qualities,” and he’s the part of Robinson that thinks it might be best to omit the bit about the tree when reciting Wordsworth’s ode in polite society. Which is to say: the park keeper is us—or, rather, he’s the sort of person we are when we’re not beguiled by magic, philosophy, or poetry, or any other activity that teases oddity out of the ordinary. Yet it should also be observed that the park keeper is astonished too: all things considered, a man saluting a tree is as odd as a tree itself. The implication is that even respectable, reasonable-minded people can’t steer clear of wonder. m att h ew be vi s u 105 Indeed, to wonder is to engage in a cognitive as well as an emotional process. When Robert Frost begins a poem with the words “I wonder about the trees,” the line is whimsical without being weakly unthinking; the poem is not about to take itself too seriously, even as it invites readers to wonder what such wondering will reveal. A similar chord is struck in Hilaire Belloc’s “The Elm,” a poem that should be prefaced with a note that the Latin word for “wonder” has its roots in an Indo-European word for “smile”: This is the place where Dorothea smiled. I did not know the reason, nor did she. But there she stood, and turned, and smiled at me: A sudden glory had bewitched the child. The corn at harvest, and a single tree. This is the place where Dorothea smiled. That’s the whole poem, but it’s hardly the whole story. The thing feels ordinary yet weirdly oracular. The speaker’s sense of the child’s “sudden glory” is an allusion to Hobbes (“laughter is nothing else but the sudden glory from some sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves”), yet the superiority theory doesn’t quite explain the strange humor of this scene. The tree—no, “a single tree”—is as enigmatic to the child as the child is to the speaker, and as the speaker is to reader. Everyone is apparently privy to something yet at the same time perplexed by it. “This is the place. ..there she stood. . .This is the place”: she and he and we can keep returning to spots like this, just as the poem ends by circling back to its opening words, smiling at them, and wondering what’s so funny. In this poetic universe, treeness is whatever you keep arriving at and whatever keeps deserting you: the unfathomable yet approachable this-ness of things, of which you are both a spectator and a participant. This last point again suggests that when we wonder at an object, we are in part wondering at ourselves—at the very fact that we can wonder at it, not simply at the strangeness of the feeling itself. Some detractors of wonder have suggested that it is merely solipsistic wallowing in the fine ineffability of our own responsiveness. I suppose 106 u rar i ta n it can be this, but it’s significant that many of the wondrous encounters I’ve discussed so far need two people to handle them (Wittgenstein and his philosopher friend; Vladimir and Estragon; Mujo and Haso; us and the park keeper; Belloc’s speaker and Dorothea). Wonder often appears to require an accomplice or a partner, somebody to help vouch for the fact that the facts are becoming strange (“Is this funny, or is it just me?”). We need wonder, like humor, to be a shared passion; wonder is a mode of being in the world that, even as it revels in the special or the singular, also contains within it the desire for a collaboration or an intimacy. In “Some Trees,” John Ashbery writes: you and I Are suddenly what the trees try To tell us we are: That their merely being there Means something This has that blend of the clarifying and mystifying that Ashbery is so often searching for (the “something” could be a Big Thing or just a sweet nothing whispered in a lover’s ear). Elsewhere, trees prompt him to see laughter in the fields: “It was existence again in all its tautness, / Playing its adolescent joke.” It’s an in-joke that often appears to need an odd couple to appreciate it, as when, in “Having a Coke with You,” Frank O’Hara reflects: in the warm New York 4 o’clock light we are drifting back and forth between each other like a tree breathing through its spectacles. To laugh or smile at this line (I laughed) is to be reminded what the wonder of falling in love feels like. It feels funny. Call it existence again in all its tautness, or call it the way people yearn to be newly yet availably strange to each other as well as to themselves (akin to Miranda’s loved-up gasp in The Tempest: “O wonder! . ..O brave new world, / That has such people in’t!”). Like a good joke, the wonder of it involves a surprise that makes some kind of sense. m att h ew be vi s u u u 107 u But trees are trees, an alm or oak Already both outside and in, And cannot, therefore, counsel folk, Who have their unity to win. —W. H. Auden, “Reflections in a Forest” Readers may be wondering (not in a good way) where all this is tending, and it might be reasonably objected that it’s difficult to see the wood for all these trees, difficult to get at the bigger picture from so many examples. Yet that difficulty is part of the point. The trees stand as an object lesson in the strangeness of our relationship with objects. We wonder about things not just when we are struggling to understand them, but as we dimly sense that it is not possible—and maybe not even desirable—to understand them. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when Bottom proclaims to his friends, “I am to discourse wonders, but ask me not what,” and when he later says to the court, “Gentles, perchance you wonder at this show, / But wonder on,” he need not be taken simply as a buffoon who shuns enlightenment. He may be confused, endlessly and hopelessly lost in wonder, but audiences admire as well as laugh at him. Maybe they would like to be him, or at least to be absorbed by similar experiences. Another way of pursuing this idea would be to ask: if wonder is so often perplexing, why is it felt to be a pleasure? And if it puts us in touch with our incapacity to account for our thoughts and feelings, why would we want it or need it? My one-year-old son does not have the answer, but he may have the beginnings of one. On a good day, he finds me most amusing. Nothing—not even a tree—is funnier than my hiding my face and then reappearing with a cry of “Peepo!” He is gasping and laughing at the return of the object that went away, and possibly at his apparent ability to coax it back into view. But he also appears to be genuinely surprised that it has come back; it’s as though recognition is shot through with a kind of curiosity or incredulity, as though a bit of 108 u rar i ta n the world has just reinvented itself afresh for his delectation. Something similar happens when I suddenly wake up to the there-ness of a tree or some other object, and to the realization that I am able to summon it to a new kind of existence from where I’m standing. Some scholars would refer to this process as “defamiliarization,” but this is too serious, too bureaucratic a word for the blithe buoyancy of moments like this, a buoyancy that can be related to the question of why we require some kinds of wonder. D. H. Lawrence finds good words to describe the action of stopping, staring, and being pleasurably astonished in “Bare Fig-Trees.” His poem begins “Fig-trees, weird fig-trees,” and they get more weirdly wonderful the longer he looks: Rather like an octopus, but strange and sweet-myriad-limbed octopus; Like a nude, like a rock-living, sweet-fleshed sea-anemone, Flourishing from the rock in a mysterious arrogance. Let me sit down beneath the many-branching candelabrum That lives upon this rock And laugh at Time, and laugh at dull Eternity, And make a joke of stale Infinity, Within the flesh-scent of this wicked tree, That has kept so many secrets up its sleeve, And has been laughing through so many ages, At man and his uncomfortablenesses, And his attempt to assure himself that what is so is not so, Up its sleeve. Let me sit down beneath this many-branching candelabrum. .. And let me notice it behave itself. This is pitched somewhere between funny-ha-ha and funny-peculiar, which is where some kinds of wonder are also pitched. Before pondering the glint of humor in the last line here, it’s worth recalling the three comic theories discussed earlier. We could say: 1. Lawrence’s tree in its “arrogance” is a dream of how one can enjoy one’s superiority to man and his uncomfortablenesses. And /or: 2. The incongruity of the tree as anemone, octopus, candelabrum, or anything m att h ew be vi s u 109 else that springs to mind is amusing. And/or: 3. It’s a relief to sit down and laugh at “Time, “Eternity,” “Infinity,” and all those other big words that make us so unhappy. Yet none of these ideas quite accounts for the banal brilliance of “let me notice it behave itself.” Trees are frequently enlisted to help people reach out to the past or to the future: they appeal to a need for roots, or for whatever is ingrained (the tree’s rings count the passing years), and they have often been read as divinatory (by the Druids, among others) or as oracular (the tree at the sanctuary of Zeus in Dodona). Lawrence’s laughing fig-tree, though, is finally apprehended only as it revels in the present, and as the speaker takes this as an invitation to follow its lead, just to sit still and be anchored in whatever happens to be going on in a newly spacious Now. The humor in the last line also has something to do with the slipperiness of “behave itself.” Is the tree on its best behavior? Or is it behaving as itself, just doing whatever trees do when they are being trees? The tree is laughing, perhaps, not simply because it feels superior, or because it’s aware of an incongruity, or because it’s in need of relief (that is: it’s not only laughing at someone, or laughing about something, or laughing off something). The tree’s laugh is not exactly a knowing, but a kind of being. Fig-trees come laden with all sorts of symbolic fruit, sacred and sexual, but this tree is beside itself with laughter because all that stuff is for the moment beside the point. The poet has been wondering about the tree as intensely as he can, but what it finally “stands for” is a life that is just standing there, sentient without being cerebral, drinking it all in, pliable and amenable to the moment. The journey from the “Rock-living” to the “manybranching” is similar to a brief, beautiful entry in one of Coleridge’s notebooks: “Amid the profoundest and most condensed constructions of hardest Thinking, the playfulness of the Boy starts up, like a wild Fig-tree from monumental Marble.” The playfulness of Lawrence’s funny tree plays on the human wish to become wild by becoming unknowing. Observers may want to graft themselves on to it in order to recuperate or to escape from their habitual need to toil after knowledge. And this yearning leads to an insight: objects of 110 u rar i ta n wonder can be emblems for a way of existing in the world of which we ourselves are envious. I say that Lawrence’s tree is “unknowing,” but a tree like this one still appears to be somehow in the know, and invites spectators to join the club. A weird taste for trees—and for wonder—leads naturally to the questions: if living but unthinking objects don’t quite “know” things, what do they seem to know of ? What can be learned from their example? Emily Dickinson imagines that “We stand on the tops of Things— / And like the Trees, look down.” In certain moods, people look down on others’ little doings (and on their own) with a calm that feels faintly comic. Maybe Dickinson’s simile also leans on the longevity of trees to suggest that we will outlive and outgrow our present worries anyway. It’s often difficult to know who—or what— the “He” of a Dickinson poem might be, but one might think of the following He as a tree. As with Lawrence’s fig-tree, this one has its secrets: Funny—to be a Century— And see the People—going by— I—should die of the Oddity— But then—I’m not so staid—as He— He keeps His Secrets safely—very— Were He to tell—extremely sorry This Bashful Globe of Ours would be— So dainty of Publicity— “Funny,” yes, sort of. Hard to say why, though, or to whom. For the tree, and for those coolly unconcerned mortals who aspire to his height, it could be amusing to look down on people. But there’s also a sense here that it’s salutary as well as funny to be confronted by the staid secrecy of things. It’s as though funniness itself—like wonder—is intimately involved with forms of nondivulgence. From this perspective, the encounter with the tree is again not dissimilar from the encounter with the strangely jocular poem. Like wondrous objects, jokes and poems present themselves without quite explaining themselves. Theodor Lipps noted that a joke “always says what it m att h ew be vi s u 111 says.. .in too few words,” and Robert Frost pinpointed the same thing when he observed that “all poetry has always said something and implied the rest.” “Getting” a good joke is like getting a good poem, especially one with a tree in it: we know something of what we’ve got, but we’re left with the feeling that something has escaped us, too. The world of our experience has suddenly become both readable and riddling. And a world in which things like poems, jokes, and trees are strangely unknowable is one in which we feel our own potentialities expand. This expanding potential can be felt in Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “Questions of Travel,” where she also thinks about the kind of wisdom that funny trees might impart—and about the kind of knowingness they might resist. After considering why we need to travel, and whether it’s worth the trouble, she stops to notice some trees behaving themselves: But surely it would have been a pity not to have seen the trees along this road, really exaggerated in their beauty, not to have seen them gesturing like noble pantomimists, robed in pink. They are “pantomimists,” I take it, because they communicate without words, in a gorgeous dumb show. Pantomimes are funny too— sometimes—and the word “gesturing” also flirts a little with the oblique comedy being acted out here. (“Gesturing” is etymologically connected with “jesting”; the dictionary links it to the Latin word gesta, meaning “doings, exploits, ” and gives earlier meanings for “jest” as “a narrative of exploits; a story, tale”). The trees’ gesturing, then, could be read as the moral of the story and as the punchline of a joke aimed at the speaker: “You should get out more!” Having said this, the trees flourish by never going anywhere. Earlier in the poem, Bishop asks: “Is it right to be watching strangers in a play / in this strangest of theaters?” Perhaps the trees encourage us to be the players, rather than to travel to watch them. So the noble pantomimists could be either supporting a need to keep on the go 112 u rar i ta n (how else should anybody have seen them?), or counseling us to take a leaf out of their book and to associate a grounded repose with a blossoming well-being. They have put down roots, and so should we. As with many encounters with wondrous, poetic trees—Philip Larkin’s, for example—“it’s like something almost being said.” But what is being said is trickier to gauge, and that’s part of what is so mysteriously funny. It’s also funny that we want the trees to say something, so keen are we for the boundless, wordless opulence of objects to speak to us by speaking for us. The situation has the makings of a rich joke: we have designs on objects, and our design is. . .that they should have designs on us. “In a forest,” Andre Marchand confesses, “I have felt many times that it was not I who was looking at the forest. I felt, on certain days, that it was rather the trees looking at me.” If this were merely narcissism dressed up as cosmic awe, then the joke would simply be on us, but it could also be seen as a human yearning for a conversable, capacious world. And wonderful objects (objects we make wonderful) seem to humor human animals for our need to avail ourselves of what’s available. Jorie Graham is enjoying this duet of mind and matter as she ponders the tree facing her window: It was not the kind of tree got at by default—imagine that— It’s not that the tree is not gettable, just that we might be implicated in what we get, or get more than we were expecting. When reading lines like this, and when imagining trees like that, it’s hard not to smile. And that smile is not exactly a knowing one; it’s more an acknowledgment than a specific type of knowledge. It’s an acceptance that we’ve been left with something to wonder about, and that we are pleased to have been left like this. u u u m att h ew be vi s u 113 imperfect friends, we men And trees since time began; and nevertheless Between us still we breed a mystery. —Edward Thomas, “The Chalk Pit” Freud suggested that “we scarcely ever know what it is that we are laughing at in a joke, even though we can settle it afterward by analytic investigation.” But it’s tricky to say when the analysis is over, and to be sure that we have settled what we know. Looking back over a few of the preceding saplings and samplings—the branches that would love to collect Social Security, the tree breathing through its spectacles, the many-branching candelabrum, the noble pantomimists—the absurd arboretum is still as strange as ever, wondrously in excess of whatever I want to do with it. Philip Fisher has argued that “we wonder at that which is a momentary surprise within a pattern that we feel confident that we know. . ..Wonder depends on an empirical run of experience in which the strange has, in the end, not turned out to be harmful.” He could just as well be describing the contours of a joke. An object of wonder and an unforeseen punch line, or pun, or witticism, all foreground the unpredictability and unintelligibility of the world without making the world feel threatening. We are briefly at a loss, while sensing that this loss is itself something of a find. It’s as if we need humor—just as we need wonder—to stay alive to the pleasure of not quite knowing things. And this pleasure increases in direct proportion to the feeling that we thought we did know what was coming, or what the thing before us was meant to be or mean. The rediscovery of the resonance of the normal, the sense that what lies closest is in fact very distant, the feeling that the unexceptional is the inexhaustible: these are the heralds of both humor and wonder. In his Lectures on the English Comic Writers, William Hazlitt paused to enjoy Voltaire’s reply to somebody who observed how tall his trees grew: “They have nothing else to do.” This treats the trees as if they had other options, as if they were something other than trees (“Well, they’re all just layabouts”), while also managing to see them exactly as they are. The quip is both disillusioned and under no 114 u rar i ta n illusions; in a strange way it accentuates—and assents to—the wonder of things by briefly imagining a world in which trees might be able to surprise you, and in which you might be able to surprise yourself. “Humor is not a mood but a way of looking at the world,” Wittgenstein observed. This is heartening because it suggests that humor could be a kind of choice, as indeed could wonder—a way of not becoming an expert on your own perceptions. “I know that’s a tree,” but then (with a shrug of the shoulders) what do I know? Returning one last time to the scene in the garden with Wittgenstein’s philosopher friend, it seems to me that the thing wouldn’t be as funny or as wonderful if the man weren’t repeating his claim to know that it’s a tree “again and again.” He’s trying to convince himself, protesting too much and so hinting at a doubt. It’s as though he’s found a new way to admit—and to enjoy—the fact that he’s not entirely sure of what he’s sure of. Wonder can be a name for what happens when amusement and bemusement meet up, and in some of its best moments the experience can gesture toward a play of thought that is also a form of therapeutic work. In his autobiography, John Ruskin recalled a time when he was trying to find a way out of depression. Rising after a sleepless night and going for a walk “in an extremely languid and woebegone condition,” he lay down on a bank. What happened next was a mundane miracle that changed his life: I found myself lying on the bank of a cart road in the sand, with no prospect whatever but that small aspen tree against the blue sky. Languidly, but not idly, I began to draw it; and as I drew, the languor passed away: the beautiful lines insisted on being traced—without weariness. More and more beautiful they became, as each rose out of the rest, and took its place in the air. With wonder increasing every instant, I saw that they “composed” themselves, by finer laws than any known of men. At last, the tree was there, and everything that I had thought before about trees, nowhere. m att h ew be vi s u 115 It’s an astonished, astonishing passage. In that first sentence, “no prospect whatever” comes from a man who feels that he has no prospects; the landscape’s prospect, it seems, echoes the speaker’s mood. But the pathetic fallacy is suddenly turned on its head: the composition of the trees slowly begins to compose him. And the more you trace and retrace some of Ruskin’s own lines, the more they make you wonder: “I found myself lying on the bank” may mean not just “I just happened to find myself there,” but also “I was lost, and in this spot I finally began to find myself, to find out who I was.” “They ‘composed’ themselves” could refer to the lines of the tree and to the pencil lines on the artist’s page. And then, “At last, the tree was there,” which perhaps points to the tree he’s drawn and to the one he’s studying. The wonder of the passage, like the wonder of the tree, is that it keeps on elaborating new relationships and new modes of being the longer you look at it. Opposed categories—inner and outer, spectator and object, artwork and world—become permeable, subject to a dazzling osmosis. In Ruskin’s universe, to wonder is to become conscious of how an act of perception may also be an act of creation—and an act of self-creation. He takes the time to make up with the world, and in the process submits to making himself up as he goes along. Everything he thought about trees is nowhere, yet nowhere feels like a good place to be. He offers readers this place as a utopia of sorts—a place where you can afford to smile at what you think you know. As John Burnside has written: “What we know / is never quite the sum / of what we find.” Funny how things turn out.