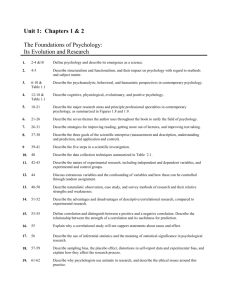

Tim Judge - Timothy A. Judge

advertisement