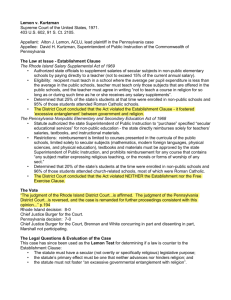

Agostini v. Felton: Thickening the Establishment Clause Stew

advertisement