MILESTONES

2010

Volume 6

A Journal of Academic Writing

Pulaski Technical College

Milestones

Volume 6

2010

Milestones is a publication of:

Pulaski Technical College

3000 West Scenic Drive

North Little Rock, Arkansas 72118

501-812-2200

www.pulaskitech.edu

1

Adviser

Joey Cole

Managing Editor

Sandy Longhorn

Editorial Board

Laura Govia

Caroline C. Lewis

Jonathan Purkiss

Consulting Editors

Amy Baldwin

Mark Barnes

Antoinette Brim

Matthew Chase

Joey Cole

Kate Evans

Leslie Lovenstein

Allen Loibner

Founding Editors

Wade Derden and Angie Macri

Design/Cover Art

Amy Green

Our Thanks To:

Dr. Dan F. Bakke; Augusta Farver; Patricia Palmer; Carol Langston; Cindy Harkey;

Purnell Henderson; David Harris; Joyce Taylor; Cindy Nesmith; Lilly Dixon; BJ

Marcotte; Tim Walbert; Melinda Gaston; Billie Egli; Michelle Verser; Tena Carrigan;

Melissa Myers Hendricks; Michelle Anderson; Ginny Peyton; Kelly Owens; Wendy

Davis and the staff of the Pulaski Technical College Libraries; members of the Pulaski

Technical College Library Committee; the staff of the Pulaski Technical College Physical Plant; Tim Jones; Amy Green; Tracy Courage; Lennon Parker; and the faculty, staff,

and students who have continued to show interest and enthusiasm in this publication.

©2011 Pulaski Technical College

Works appearing in Milestones are printed with the permission of the authors. Copyright

reverts to authors immediately following publication.

Milestones is published annually by Pulaski Technical College through the Division of

Fine Arts and Humanities.

Submissions to Milestones are accepted year-round via e-mail at milestones@pulaskitech.edu.

The publication accepts academic essays, personal narratives, and creative nonfiction.

Anyone associated with Pulaski Technical College is encouraged to submit to Milestones.

The views and opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of Pulaski Technical

College or those of any of the college personnel or people responsible for publishing this

journal.

Please note: The language and content contained in this journal may not be suitable for

all readers.

2

MILESTONES

2010

Volume 6

TA B L E O F C O N T E N T S

Life Long Friends:

5th Annual National Library Week Essay Contest Winner

Judith Spradling

5

Langston Hughes: A Great Writer with an Ordinary Flair

J. Renee’ Baker

8

Population of Loss

James Dunlap

12

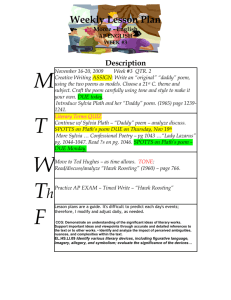

Symbolism, Violence, and Language in Sylvia Plath’s Poetry

Stefani Chaney

16

Poe’s Insanity: Character or Truth?

Roxanne Nichole Litchholt

21

What Barbie Dolls are Made Of

Lauren Morgan

25

Dante’s Inferno and the Nature of Sin

Bryan G. Tribble

29

Looking Down the Tracks

Penny Davis Riggs

32

Turn that Noise Down

Kathy Jacuzzi Fluharty

40

3

4

5th Annual National Library Week Essay Contest Winner

JUDITH SPRADLING

Life Long Friends

I have carried with me the wisdom of friends, perused their adventures, and

waited patiently through long narrations. There have been tears both celebratory and

grief-stricken, past and present, amidst companions, confidants, and accomplices, waiting quietly in the background or noisily interjected. Disguised and often overlooked, I

have carried the quiet murmur of their words reoccurring in odd places, dark corners,

worn and battered with age or bright and newly acquired. They are quiet friends, new

and old friends, comfortable like old shoes, the ones you slide into knowing the feel and

fit. These friends sustain on cold nights and long trips, imprinting themselves with

laughter or tears, making them part of your life, part of who you are and will become.

They are always just around the corner, down the road, or concealed on the next page.

I carry them with me, thankful for the small town where we met and the elderly woman

who introduced us.

In my mind, the elderly matron nicknamed “The Keeper” had always been the

librarian, as steadfast and reliable as the oak floors, windows, and doors of our small

town library. She would arrive punctually, unlocking the door at exactly the precise

hour, and, watching from the deserted gas station, I would cross the two-lane highway

where I always waited, casually making my way to line up along with the others,

cautiously inching along in a regimental, single file fashion to the large oak desk.

Jacketed covers up, the children’s books placed precisely on the right hand corner of the

desk in the designated square, the books underwent a thorough inspection.

Occasionally there was a fine for damages or loss, but the usual order of business was the

oral book report required as to our perception of the reading material. There would be

shifting and squirming as The Keeper’s sharp eyes ferreted out those who had only

managed half a book or relied on the illustrations. Still I arrived along with neighborhood

children, a younger sibling in tow, waiting for The Keeper’s timely appearance, enduring the literary inquisition in a ritualistic manner: a clandestine meeting, Monday after

Monday and occasionally on Wednesday or Saturday. I placed my returns on the large

oak desk, waiting, standing tall in anticipation of the inquisition. “Could you please

wait … over there … until I am finished?” she asked and directed as I placed my books

into the outlined square. Perplexed by The Keeper’s request, I nervously shuffled to

the window behind the gigantic desk as directed and waited. Released without inquisition and directed to the rear, the remaining children eyed me with suspicion, my own

sister turning her back, deserting me for the lure of brightly illustrated storybooks.

Somewhere a fan whirred softly, children giggled, and the slap, scrape, slap rhythmic

cadence of cards sliding into the jackets of new literary selections registered as white

noise against my imagined transgression.

5

Her immediate tasks complete, The Keeper turned, measuring my worth

against an invisible standard. “Did you finish all of these?” she probed, indicating my

stack of returns. “Yes, ma’am,” I replied, my voice small. “I’ve read them before.”

“I am well aware of the books you have read and exactly how many times you

have read them,” she announced stiffly adjusting her glasses. “I suppose allowances

could be made. Rules are, after all, merely guidelines.”

The Keeper rose from her chair as Athena rising in judgment, iron-gray hair,

reflecting under the glare of the naked florescent bulbs. “Follow me please.” Her voice

commanded obedience as she motioned me forward, the drum of our feet loud on the

oak floor. I followed, head down, expecting expulsion, noting our shadows as we moved

beyond the hum of children engaged among their books, my mind creating images of

my body flung violently through the open door to the hot sidewalk in violation of some

unknown rule.

“I suggest you select your books from this section, beginning with these,” the

Keeper stated, stopping to indicate the rows of books referred to as “The Tombs.” She

pulled from the shelves two or three volumes, holding them before me while I stared

mesmerized by the red letters of the sign prominently displayed overhead – “This section

not intended for children.” Somehow, I had arrived, vaulting over the boredom of repetitive juvenile purgatory to the adult mecca of unknown wealth. My adolescent sense of

drama was engaged as The Keeper placed the selected volumes into my hands, instilling in me a sense of awe. I touched the jacketed books, stroking their bindings, respectful of the pages, the authors, the black and white images that would move as

pictures through my mind. “These were a few of my favorites when I was young.” She

stopped to look directly at me, seeing into the void of my adolescent soul, before saying, “They still are.” She left me there inundated by my sense of awe, the smell of

lemon oil and paper permeating the air.

With a voracious addiction aided by suggestions from The Keeper, I journeyed

through the burning of Atlanta with Scarlett O’Hara, was enamored by Jane Eyre’s

Edward Rochester, and befriended Elizabeth Bennett and Mr. Darcy. I read beyond the

classics, incorporating novels that explored the deterioration of Alzheimer’s and the

degeneration of humanity in historical biographies, debating the morality and wisdom

of authors with the gray-haired librarian. I read and absorbed, my mind fed by the

wealth of information available in that small library.

Shakespeare, Faulkner, Hawthorne, and Poe, amid the company of endless

other authors, ingraining themselves unconsciously onto the small particles of my

cognizant self, helped guide the creation of my intellectual future—their living work

transcending beyond the strokes of paper and pen, steering a course I might not have

considered—as did the librarian who introduced me into their company. Time has erased

the face and name of that librarian, and I have moved past small-town living to rambling

multi-storied structures of literary proportions. Yet my mind reverts to that little library

and its Keeper with a fondness and propensity toward darkened alleys of books, the

smell of aging paper and lemon oil, and the squeak of oak floors. It is a fondness

reminiscent of childhood, summer days, and lifelong friends.

6

On an ordinary map, M 99 makes a sharp right turn between a derelict gas

station and a sad white building. The door sags obscurely on rusty hinges, sandwiched

between tired, weather-beaten storefronts and crumbling sidewalks. Admittance is scant,

the hours random and scarce during the long slumber of winter, awakening as the

crocuses lift their heads toward spring’s kiss. A forgotten treasure in a dying town, the

door groans, standing open, admitting the children of summer complete with popsicles

dripping, staining the concrete blue and green. It is this memory of childhood where on

a hot summer day I long for the cool taste of raspberry, detailed debates, and the company of good friends, lifelong friends, first introduced on long summer days.

7

J. RENEE’ BAKER

Langston Hughes:

A Great Writer with an Ordinary Flair

In his poems, “Song for a Dark Girl” and “Birmingham Sunday (September 15,

1963),” Langston Hughes describes the brutality that was inflicted upon some African

Americans during their struggle for civil rights. In “Song for a Dark Girl,” the girl has

witnessed the murder of her lover and is relating the experience. In his poem, “Birmingham Sunday (September 15, 1963),” four little black girls are killed in a church

bombing. Through his poetry, Hughes captures the dark moments in African-American

history. Both poems have similarities like the murder and death involving people of

African heritage and both are very powerful ballads; however, each is different in its

own setting. Evidence of the way these monstrous tragedies affected Hughes is depicted in the injustice and inequalities he speaks of throughout his simple, yet relevant

writings.

Hughes began to face many obstacles early in life, which could account for his writing with such passion and depth. According to Saunders Redding, after

divorcing her husband, Hughes’ mother was unable to support her family, so she moved

in with her mother. Being raised by his mother and grandmother, Hughes was exposed

to The Bible as well as stories about slaves and their struggle for freedom by his grandmother. Also, the knowledge of how his grandfather died beside activist John Brown

would have a major influence in his development as a poetic writer. While still a senior in high school, he started to write poetry and was chosen by his peers (mostly white)

as class poet of the year. As noted in Redding’s essay, “Hughes spent the next year in

Mexico with his father, who tried to discourage him from writing.” Nevertheless, he did

not allow this to prevent him from becoming one of America’s greatest and most wellknown black writers of this century.

“Song for a Dark Girl” was written in 1927, a time when lynching a black person was a common occurrence. The speaker states, “They hung my black young lover

/ To a cross roads tree” (lines 3-4). Hughes was directly exposed to the discrimination

and mistreatment that most African Americans were plagued with while growing up in

the 1920s. The black American ghetto life was the subject of quite a few of his poems.

He used the blues and jazz rhythms that the African-Americans were accustomed to

listening to on a daily basis in his writing. African-American people and their community were the focus for much of Hughes’ poetry. These poems show evidence of how

the prevalence of lynching and murder troubled Hughes, and how he chose to disclose

his feelings by writing about it.

Hughes was a distinctive voice that expressed the feelings of the AfricanAmerican people. He spoke through his poetry and also voiced his opinion when the occasion called for it. In his poem “Birmingham Sunday (September 15, 1963),” he

depicts the violence and brutality experienced by the African-American people during

this time. This poem represents the feelings and thoughts of African Americans who

were afraid to voice their opinions out loud because of what might happen to them,

8

their families, friends, or neighbors. For example, the four little girls in the poem, who

were based on real victims of a bombing, were in church worshipping and learning

about God when this awful attack came upon them by surprise and took their young

lives. Hughes was obviously affected and moved to write this poem. He shows this fact

by stating:

Their blood upon the wall

With spattered flesh

And bloodied Sunday dresses

Torn to shreds by dynamite (5-8)

This stanza gives a vivid picture of this particular incident, showing that many blacks,

especially black men, were commonly murdered during this period in American history,

but to murder “[f]our tiny girls” was an even more despicable act of hatred towards the

African-American community (15). Hughes’ poems expose the shame of these ugly

truths, and it is evident in Hughes’ poetry that these same acts of cruelty that were being

inflicted upon blacks in the 1920s were also being committed in 1963.

In the two poems, Hughes is revealing the continuing racial prejudice in America. In “Birmingham Sunday (September 15, 1963),” the reader knows this bombing and

the murder of the four little girls did actually take place. In “Song for a Dark Girl,”

there is no true evidence of who the girl is or who her lover is. The poem states only

that a murder occurred and that the victim was her lover. Here Hughes is making an

implicit point, no doubt, and it is not important whether we know the victim or the girl.

The main thing we need to know is that such murders were rampant and that this poem

is highlighting this horrific fact. The girl in the poem is depicted as feeling forsaken, and

Hughes reveals this by her stating, “I asked the white Lord Jesus / What was the use of

prayer” (7-8). These lines reflect the hopelessness that the girl was feeling as she

watched her lover hanging on that tree. Also, these lines address the issues relating to

the lynchings that happened so often during the time when African Americans were

striving to be treated with respect and dignity. In the course of the time when Hughes

wrote “Song for a Dark Girl” and “Birmingham Sunday (September 15, 1963),” his

writings became more direct and to the point. They express the difference that only

life’s personal experience can provide, which is shown in his well-developed diction and

colorful tone.

Hughes had traveled widely between 1927 and 1967 and had become

established as he polished his poetry and honed his perspective to the extent that he

was hugely admired as a poet, mainly in the black community. In the essay “The Poetic Consciousness of Langston Hughes from Affirmation to Revolution,” Calvin Hernton states that some critics complain that Hughes’ writing is weak and demeaning

because the language is so plain and does not carry the basic literary connotations. Interpretation, it seems, is very important to Hughes. During his travels, he encountered

a variety of cultures, and he gained knowledge of people in general. His extensive association with people inspired him and showed in the way he was partial to the “people’s cause” during his many travels. In his essay, Hernton notices and remarks that

“not only was Hughes a poet of the New Negro/Harlem Renaissance, he was also a

poet of the legacy of the Russian Revolution and other revolutions of his times.” Therefore, he writes in a style that is spirited; there is little to no doubt to the meaning or

choice of his words. Hughes makes it clear in the poem by writing that “Four tiny girls

9

/ Who left their blood upon that wall, / In little graves today await” (15-17). By doing

this, he spotlights African-American life because of the troubled times that he experienced universally and

personally. He uses direct and resolute language because it

is easy to understand, and his writing reflects the language most often used by the

African-American communities he visited during his travels.

Hughes wrote many poems between 1927 and 1967 and gained 40 years of

knowledge through the experience of living through times when it was difficult for a

man of color to exist as an equal. It seems that his attitude remained concerned and attentive, yet he shows a distinction in these time periods and the different ways in which

white America implemented these atrocious acts. Although the methods of death are

quite different, they are still ghastly. His writing style matured to the extent that he

could use other methods to relate his message. For example, his double use of the Chinese dragon symbol in “Birmingham Sunday (September 15, 1963),” “The dynamite

that might ignite / The fuse of centuries of Dragon Kings” (18-19), was not used in his

earlier poems. He uses China’s myth about the dragon being a force that dispenses

blessings to the dead as well as to the living; however, the symbol of the dragon also

refers to the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. Meanwhile, Hughes continued to use

the ballad form, and it depicts sadness and sorrow in telling of death and destruction that

Hughes shows us in writing, “Four little girls / Who went to Sunday School that day /

And never came back home at all” (1-3). In this instance, his writing style seems to be

more refined than it was in many of his earlier works. Hughes was writing in a different time, but the same concerns are apparent in his writing, and it still depicts his ethnicity and where he came from.

In conclusion, Hughes was very effective in displaying the injustice and inequalities that were thrust upon African Americans in the 20th century. Hernton further

states that “[t]he poetry of Langston Hughes is imbued with a consciousness of black

people which has always awed and inspired me.” This statement shows that Hughes’ literary works not only speak to the black community, but they also speak to all people

regardless of their ethnicity. America was built with the help of African Americans and,

without that help, America might not be the great country it is today. By writing in the

speech of a common man, Hughes gives tremendous insight into the mind and spirit of

African-American culture. Thus, Hughes’ poetry endures down through the generations, and his poetry is still read by many different cultures today.

10

Works Cited

Hernton, Calvin. ”The Poetic Consciousness of Langston Hughes from Affirmation to

Revolution.” Langston Hughes Review 12.1 (Spring 1993): 2-9. Rpt. in Poetry

Criticism. Ed. Timothy J Sisler. Vol. 53. Detroit: Gale, 2004. Literature

Resource Center. Web. 3 Apr. 2010.

Hughes, Langston. “Birmingham Sunday (September 15, 1963).” Literature, Reading,

Reacting, Writing. Ed. Laurie G. Kirszner and Stephen R. Mandell. Compact 7th

ed. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010. 962-963. Print.

---. “Song for a Dark Girl.” Literature, Reading, Reacting, Writing. Ed. Laurie G.

Kirszner and Stephen R. Mandell. Compact 7th ed. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage

Learning, 2010. 959. Print.

Redding, Saunders. “Hughes, Langston (1902-1967).” Encyclopedia of World Biography.

2nd ed. Gale. 1998. Student Resource Center – College Edition Expanded. Web. 3

Apr. 2010.

11

JAMES DUNLAP

Population of Loss

According to the introduction to James Joyce in Literature: Reading, Reacting,

Writing, the author of “Araby” grew up in Dublin in the late 1800s. He was sent to a

school for priesthood, but soon after his studies, he rebelled and went to Paris. There

he raised a family with Nora Barnacle, whom he didn’t marry for 27 years (Kirszner

375). This kind of life gave him a unique way of presenting his stories. Likewise, the

author of “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” T.S. Eliot went to Paris to further his

studies. While there he struck up a friendship with a fellow lodger and medical student

named Jean Verdenal. After Verdenal died in the Battle of the Dardanelles, Eliot wrote

and dedicated his landmark poem, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” to him

(Bush). These two authors have many similarities in their writing. One of those

similarities is that the main character in both Joyce’s story and Eliot’s poem questions

whether to make known his innermost feelings, and Joyce and Eliot use similar imagery to describe women. In both works, there are also moments where it all becomes

almost too much for the characters. While the two works are definitely aiming at two

different things, they are similar in nature. The two main characters have an epiphany

that the things they pursued are all in vain. For Joyce’s boy, it is the girl; for Eliot’s

Prufrock, it is understanding and a way to reveal his true self.

When a person realizes that he or she has strong feelings for someone else,

there is often that element of doubt, that question of whether to tell or not. The same

can be said for those who find they do not have the same feelings for another. In Joyce’s

“Araby,” this point is illustrated when the boy describes his feelings for Mangan’s sister. The boy states, “I did not know whether I would ever speak to her or not or, if I

spoke to her, how I could tell her of my confused adoration” (377). The young boy is

feeling the effects of a crush. He seems resigned to not talking to the girl because he will

not be able to explain his feelings. This is also how the speaker feels in Eliot’s poem,

“The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock.” He is reduced to inaction for fear that he cannot convey his feelings and fear of the reaction he might get. Eliot sums it by saying, “Do I dare / Disturb the universe?” (lines 45-46). This anxiety increases as the

story and poem progress. In fact the emotions almost boil over.

Everyone has his or her breaking point, and these two characters are no different. The boy in Joyce’s story nearly reaches this point. He is up in the parlor, alone and

in the dark; he hears the girl’s voice and almost loses control. He muses, “All my senses

seemed to desire to veil themselves and, feeling that I was about to slip from them, I

pressed my hands together until they trembled, murmuring: ‘Oh Love! Oh Love!’ many

times” (377). The boy is trying not to defile himself. What can be pulled from this is

just how strongly he feels and how hard it is for him to contain these feelings. Similarly,

in Eliot’s poem, his speaker is mulling over whether he should tell a woman his feelings at all costs. He states throughout the poem that he knows how he will be seen and

treated, but he questions whether he should explain himself. He, like the little boy,

reaches a frantic moment, which is revealed when he says, “Should I, after tea and cake

and ices, / Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis? / … I have wept and

12

fasted, wept and prayed” (79-81). The boy in “Araby” is in effect praying just like

Prufrock. At this moment they both come very close to acting on their urges. The emotion of the story and poem is coupled with a strong use of imagery.

Both writers use imagery to accentuate these scenes and emotions. A cat is

used in Eliot’s poem to symbolize the fog (15-23). Meanwhile, there is a harp used in

Joyce’s story to symbolize his love interest (377). Both works describe a female who

wears bracelets. In this part of “Araby,” the girl is actually talking to the little boy. She

explains she cannot go to Araby, a bazaar. Joyce lends a little detail and shows her intent when he writes, “While she spoke she turned a silver bracelet round and round her

wrist” (377). This simple detail shows she is trying to appeal to the boy in a time when

this little bit of the flesh would be quite showing. Eliot uses a similar description in his

poem. After the speaker envisions what will happen if he spills out his innermost feelings, he then takes a moment to talk about how the woman repulses him. Prufrock says,

“And I have known the arms already, known them all – / Arms that are braceleted and

white and bare” (62-63). While Joyce’s character is getting closer to finding out the

girl does not like him the same way he likes her, Prufrock is getting closer to realizing

he can never tell a woman his feelings. For Prufrock, it is just more reasoning and worrying, while Joyce’s boy has to swallow a disappointing moment.

Both male characters experience their epiphanies in different ways. In Joyce’s

story, everything has built to the boy going to Araby. This is his one shot at gaining

favor with the apple of his eye. He has not really thought of how she feels about him.

He is so infatuated that he becomes narrow-sighted. He thinks of nothing but her. A

simple event leads him to his epiphany, and a small event crushes him. He has finally

made it to Araby, but everything is closing, and he sees a young lady, probably no older

than his girl, talking with two young men. He quickly sees that he was used and is

devastated. Joyce explains the boy’s feelings by stating, “Gazing up into the darkness

I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity” (379). He ultimately

understands his desire was all in vain and he has no future with the girl. Prufrock’s

epiphany is a little different, however. At this point in Eliot’s poem, Prufrock is

analyzing his options and trying to will himself into action. He takes the reader to when

he is old and hints that he will never act out his feelings and that he will live out the rest

of his life burdened. Eliot makes it clear when Prufrock declares, “I have heard the

mermaids singing, each to each. // I do not think they will sing to me” (125-26). Both

characters equally share in the desolation of wasted emotion. Joyce’s boy will never

look at the girl the same way. He is crushed that someone he admired so much could

be so cruel. Along the same lines, Eliot’s Prufrock will have to live out his days with

the restriction he has felt. He will never be who he is, but rather will continue as everyone else thinks he should be. In a way neither of the narrators is able to act out his feelings.

As Dante Alighieri writes of the gates into hell in The Inferno, “Through me

you enter into the city of woes / through me you enter into eternal pain / Through me

you enter the population of loss”… “Abandon all hope, you who enter here” (III.1-3,

9). Hell has long been a home for those of a single-minded pursuit. This seems to be

the case for the little boy in “Araby” and J. Alfred Prufrock. One might be inclined to

think they were both in hell on earth, given their situation. For the boy, this is a hard13

learned life lesson. As for Prufrock, he may never be truly happy. As literature often reflects the life of the writer, it is interesting to note that Joyce rebelled against his

religious heritage (Kirszner 375). Eliot, on the other hand, drew more and more on his

religion as his life went on. In fact he wrote a lot of Christian material further along in

his career (Bush). Though they share a common thread, which is in writing and in a religious upbringing, the two authors couldn’t be more different. Like their characters,

Joyce and Eliot suffered trials and lived with their decisions, making the best out of

each obstacle, and that’s the human experience.

14

Works Cited

Alighieri, Dante. The Inferno. Trans. John Ciardi. New York: NAL, 1971. Print.

Bush, Ronald. “T.S. Eliot’s Life and Career.” American National Biography. Ed. John A.

Garraty and Mark C. Carnes. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Modern American

Poetry. Web. 8 Feb. 2010.

Eliot, T.S. “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Kirszner and Mandell 1017-1021.

Print.

Joyce, James. “Araby.” Kirszner and Mandell 375-379. Print.

Kirszner, Laurie G., and Stephen R. Mandell. “James Joyce.” 375. Print.

---. Literature: Reading, Reacting, Writing. Ed. Laurie G. Kirszner and Stephen R.

Mandell. Compact 7th ed. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010. Print.

15

S T E FA N I C H A N E Y

Symbolism, Violence, and Language

in Sylvia Plath’s Poetry

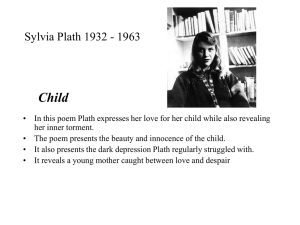

Sylvia Plath is well known for her unique use of language and imagery

throughout her poetry. Plath used poetry to express the ordeals that she and many other

women faced in their lifetime. These ordeals are the main themes of her poems, and they

range from oppression to marriage to childbearing. Plath used many experiences from

her life as examples in her writing to express her inner frustrations. In fact, most of her

poetry deals with a woman’s struggle of finding her place in society. Although Plath is

admired for her subject matter concerning the choices that women must face, she is

just as well known for her violent and sometimes vicious poetry. Three of her poems,

“Daddy,” “Mirror,” and “Lady Lazarus,” exemplify Plath’s unusual use of

violence, symbolism, and wording.

Symbols and metaphors are abundant throughout Plath’s poetry. Some of her

most common images are references to the horrors of the Holocaust. In particular,

“Daddy” is filled with some of Plath’s darkest Holocaustic symbols. In this poem, Plath

places herself in the role of a victim. Plath writes, “I began to talk like a Jew / I think

I may well be a Jew” (lines 34-35). In “‘This Holocaust I Walk In:’ Consuming Violence

in Sylvia Plath’s Poetry,” Jacqueline Shea Murphy reveals that Plath actually “wrote the

bulk of these poems almost two decades after the war.” Murphy then continues by noting another behind Plath’s use of the Holocaust. She states that it is not just a political

statement that is “connected to her keen sensitivity to political horrors” but that mostly

it is “inextricably tied to the immediate personal struggles she faced as a woman.”

While Plath may have written about the Holocaust long after it actually happened, the

effects are the same. The metaphors of Nazis and Jews are Plath’s own personal and political way of describing gender and oppression. The suppression of an entire race

through the use of violence is a measure against the extremity of her own personal feelings of suppression due to her gender.

Ordinary everyday images are also found in “Daddy.” Symbols, like a black

shoe suffocating a foot, set the tone for the speaker’s feelings. For example, in using

the shoe image the speaker states, “In which I have lived like a foot / For thirty years,

poor and white” (4-5). Meanwhile, some of the metaphors are more subtle. Such is the

case in “Mirror” and how, during the course of the poem, the mirror changes itself and

its reflections, claiming, “Most of the time I meditate on the opposite wall” and “Now

I am a lake” (6, 10). The woman analyzing her reflection defines every woman’s desire

for perfection in what she sees, when she relates, “A woman bends over me / searching my reaches for what she really is” (9-10). According to William Freedman in “The

Monster in Plath’s Mirror,” the woman who plays the key role in “Mirror” wants to see

her reflection showing herself as the “male-defined ideal…the woman who desires to

remain forever the young girl…for confirmation of the man-pleasing myth of perpetual

youth, docility, and sexual allure.” Freedmen makes a wonderful point in his interpreta16

tion of the poem. The reflection that Plath describes is nothing more than one woman’s

desire to be approved by the “male-defined ideal” of perfection, and, in doing so, she

loses touch with her true self-worth.

Furthermore, the title of one of Plath’s better-known poems is a symbol in of

itself. “Lady Lazarus” brings to mind the biblical story of Lazarus, the man who was

raised from the dead. However, in Plath’s version, she narrates how she is once again

rising from one of her suicide attempts. The speaker in the poem claims, “Dying / Is

an art like everything else. / I do it exceptionally well” (43-45). “Lady Lazarus”

continues on in its many metaphors with its description of Plath’s life. As in when the

speaker describes herself with “And I am only thirty / And like the cat I have nine times

to die” (20-21). In a sense, she is conveying to the reader not only the innumerable

attempts at suicide she has taken, but also how she is able to so easily convey her

emotions about it.

The gruesome symbols of dead or mutilated bodies are abundant throughout

Plath’s poetry. Again, Murphy notes about the violence in "Daddy" and "Lady Lazarus"

that there is an obvious connection between “violent control of bodies in history” and

gender oppression. Murphy continues, “In them, the speaker moves from the position

of the oppressed – the Jew, the mutilated concentration camp victim – to that of the

oppressor, capable of killing and consuming others' flesh.” It is in these bodies’ changes

from oppressed to oppressor that Plath is urging readers to take control of their own actions and fate. By refusing to be oppressed, Plath was able to achieve her goals of creativity through her writing.

Another one of Plath’s most unique traits is the amount of violent images and

scenes in her work. A large amount of this violence stemmed from Plath’s life; she

famously suffered with severe bouts of depression, which led to several suicide attempts.

Plath was able to translate the inner violence of her emotions into her poetry. Likewise,

as Jeannine Dobbs points out in “‘Viciousness in the Kitchen’: Sylvia Plath’s Domestic Poetry,” Plath was known for frequently depicting “physical and mental pain as retribution for doing or being bad,” and Dobbs links a connection between “images that

associate physical and mental suffering…with domestic relationships and/or domestic

roles.” Plath’s poetry often expressed frustration about the confusing, conflicting desires

to be a free independent woman, yet still be capable of being desired by men.

A portion of that domestic role is shown in “Mirror,” and while it is Plath’s ode

to one woman’s search for perfection, it is also about how that search can sour other aspects of life. While this poem is not one of Plath’s more particularly violent works, its

subtle viciousness is hidden in the context. The lines “What ever I see I swallow immediately” and “I am not cruel, only truthful” (2, 4) reveal the bluntness of the mirror’s reflection. The final line reveals the true reasoning behind the poem’s meaning. The

mirror recounts, “In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman / rises

toward her day after day, like a terrible fish” (17-18). The revelation at the end of “Mirror” acknowledges Plath’s opinion on the fate of how any search for perfection is met.

The cruelty in the poem’s final line sends the message that only woman alone can take

control and break free of the barriers that society and men have placed on her to live life

freely. Perfection is a matter of choice because, no matter what, death awaits in the end.

Another perspective is what could arguably have been one of Plath’s worst fears, that

17

the only one suppressing her was herself. As Freedmen observes, the poem shows a

“suppression of self” and consequently “the last image the reflector swallows is that of

the terrible fish, which is at once its concealed opposite and its concealing self.”

The oppression of woman’s control of her own life leads to many violent symbols and images. The theme of male-enforced repression is continued even further in

“Daddy,” where the male figures are described as vampires, both of whom the speaker

is forced to kill to survive. She pronounces, “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two”

(71). Again, the influence of patriarchs on Plath’s life also greatly affected her poetry.

Yet the effects of Plath’s expression of violence do not stop there, as Jahan Ramazani

notes in “Daddy, I Have Had to Kill You: Plath, Rage, and the Modern Elegy.”

Ramazani acknowledges that “Plath broke taboos…on female expressions of rage….

The daughter's elegy for the father became, with her help, one of the subgenres that

enabled women writers to voice anti-patriarchal anger in poetry.” By refusing to reign

in the aggression in her poetry, Plath’s use of violence tore down barriers that would

have otherwise repressed the next generations of women.

Lastly, Plath’s attempts at suicide are referenced throughout her poetry. One example is how she delicately describes some of her reasoning, her longing to be back

with her father. As the speaker states in “Daddy,” “I was ten when they buried you / At

twenty I tried to die / And get back, back, back to you” (57-59). Plath’s past is brought

to light in her retelling of the biblical story of Lazarus. This story, of the dead rising

again, is the perfect format for Plath to be as vivid in her images and metaphors as she

wishes, writing “Ash, ash – / You poke and stir. / Flesh, bone, there is nothing there”

(73-75). As is the situation in “Mirror,” the true meaning is only revealed at the end. In

this case, true to her skewed form, the speaker has risen from death only to seek revenge

in the form of more deaths. At the end of the poem, she promises, “Out of the ash / I

rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air” (82-84). According to Murphy, on Plath’s

uses of bodies, the “cut bodies, perfect dead bodies, feverish bodies, are authoritative

texts to be read. This configuration flips the dichotomy of oppressor/oppressed, so the

oppressed body ends up on the top,” while also as creative outlets these bodies helped

Plath create “texts from pain, her mutilated body becomes a source and manifestation

of her power.” “Lady Lazarus” could arguably be Plath’s most violent in terms of

imagery. As Murphy states above, the use of bodies and their various shapes of health

are critical to understanding the meaning of the specific poem in which they are placed.

Like all writers do, Plath took great care in her choice of wording. Yet, it is her

purposeful use of words and phrases that makes the most pronounced impact on the

reader. She exchanged words to carefully craft her metaphors and cause shock. Some of

her delights in language range from curse words to repetitions to get her point across.

One of Plath’s greater uses of language is how seamlessly she switches from

English to German in “Daddy.” After spending most of the poem referencing Germany,

the speaker breaks into the poem with a mixture of English and German, crying, “Ich,

ich, ich, ich. / I could hardly speak” (27-28). Plath often resorted to repetition to further prove her point, such as the constant repeating of the previous stanza and the repetition at the beginning of the poem, “You do not do”(1). The repetition in “Daddy”

works to force, not only herself but her readers as well, to believe the finality of her obsession with her father’s approval. Brita Lindbergh-Seyersted’s “‘Bad’ Language Can

18

Be Good: Slang and Other Expressions of Extreme Informality in Sylvia Plath’s Poetry”

affirms Plath’s use of words in “Daddy” by noting that “[t]he picture of the authoritarian,

fear-inspiring father that the poem offers, receives quite logically its spiteful

finishing touch in the 'bastard' epithet, but several clowning words…justify a different

interpretation.” Lindbergh-Seyersted is correct in her point; the whole purpose of Plath’s

careful crafting of words and placement are what best gets the point across. “Daddy’s”

beginning repetition sends the reader into a lull. This is followed by nonsensical, yet

playful words that are meant to lure the reader into a sense of the speaker’s passiveness

only to be shocked by the finality of the speaker’s decisiveness. In “Mirror,” Plath again

uses repetition and twisted words to reach her meaning. In this case, the soft repetition

of “day” gives the reader the image of a slowing rising dark fate of a “terrible” end. The

old woman “[r]ises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish” (18). Part of Plath’s

gift with language is how she references it and its ability to be distorted in her poems.

The speaker points out how just a trick of light can mislead others, stating, “Then she

turns to those liars, the candles or the moon” (13).

Slang is also widely used in Plath’s poetry. In “Lady Lazarus,” “What a trash

/ To annihilate each decade” (23-24) is a play on words in slang form. “What a trash”

could just as easily be translated to “What a drag” in order to show her laissez-faire approach to the tragedy of her deaths. Yet, at the same time, this phrase is describing her

approach to life as nothing more than “trash,” or a waste.

Plath’s selection of words and phrases can change the context and the mood of

the speaker. In this instance, the speaker is able to easily convey how the audience

views her tragedy with the simple hints of a show, as the audience watches “Them unwrap me hand in foot – / The big strip tease / Gentlemen, ladies” (28-30). As Joyce

Carol Oates asserts in “The Death Throes of Romanticism: The Poems of Sylvia Plath,”

the speaker “does not expect a sympathetic response from the mob of spectators that

crowd in to view her.” The careful placement of wording in “Lady Lazarus” is what

makes the most dramatic impact on the reader. Plath is able to delicately separate the

cruel risen-again speaker from its victim of the insipid crowd. It is these simple choices

that a writer makes that can have a most profound effect on the readers.

“Daddy,” “Mirror,” and “Lady Lazarus” are just three of the many poems that

show Plath’s wide range of writing. She was able to transfer the violent emotions that

would eventually destroy her into creative expressions in her poetry. These creative expressions would remain long after she ended her life and change the way the public

views female writers. Still, while Plath was an unconventional writer who focused on

less-than-ideal feminine topics, her work reverberates still to this day with women from

all walks of life. Whether it is in her range of topics (a parent’s lasting effects, a satisfaction in one’s reflection, or a skewed look at death) or her choice of how the poems

will make the most dramatic effects (symbolism, imagery, or wording), Plath’s poetry

gives its readers plenty to ponder over.

19

Works Cited

Dobbs, Jeannine. “‘Viciousness in the Kitchen’: Sylvia Plath’s Domestic Poetry.” Modern

Language Studies 7.2 (1977): 11-25. Literature Resource Center. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Freedmen, William. “The Monster in Plath’s Mirror.” Papers on Language and Literature

108.5 (Oct. 1993): 152-169. Literature Resource Center. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Lindbergh-Seyersted, Brita. “‘Bad’ Language Can Be Good: Slang and Other Expressions of

Extreme Informality in Sylvia Plath’s Poetry.” English Studies 78.1 (Jan. 1977): 19-31.

Literature Resource Center. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Murphy, Jacqueline Shea. “‘This Holocaust I Walk In:’ Consuming Violence in Sylvia Plath’s

Poetry.” Bucknell Review 39.1 (1995): 104-117. Literature Resource Center. Web. 27

Nov. 2009.

Oates, Joyce Carol. “The Death Throes of Romanticism: The Poems of Sylvia Plath.” The

Southern Review 9.3 (Summer 1973): 501-502. Literature Resource Center. Web. 27

Nov. 2009.

Plath, Sylvia. The Collected Poems. Ed. Ted Hughes. New York: Harper, 2008. Print.

Ramazani, Jahan. “Daddy, I Have Had to Kill You: Plath, Rage, and the Modern Elegy.”

PMLA 108.5 (Oct. 1993): 1142-1156. Literature Resource Center. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

20

R O X A N N E N I C H O L E L I T C H H O LT

Poe’s Insanity: Character or Truth?

The short story, “The Black Cat,” written by Edgar Allan Poe, is the narrator’s

in-depth confession on the eve of his execution. In the opening lines of the story, the

narrator states, “For the most wild yet most homely narrative which I am about to pen,

I neither expect nor solicit belief” (Poe 522). This opening, along with many other

events throughout the story, has different interpretations depending on the reader’s

analysis of this tale. In Poe’s “The Black Cat,” he is able to capture his audience’s

attention with hidden meanings buried throughout the story with his use of imagery

and symbolism. Poe’s main character, the unnamed narrator, carries an essence of madness

many readers believe to be a direct projection of the inner thoughts of Poe himself.

Within this story of murder, Poe entices the reader to examine the validity of the

narrator’s account of the violent crimes he commits. Through Poe’s expert use of horror, graphic detail, and irony, he attaches symbolism and imagery to his characters and

the events leading up to the final murder of the narrator’s wife.

The first of many heinous crimes that the narrator performs in “The Black Cat”

is the inhumane gouging of the eye of the beloved family cat, Pluto. Even though the

narrator describes the cat fondly before this first act of violence, his aggression escalates to include killing Pluto by hanging the cat from a tree in the front yard. The narrator views the cat as a driving force or demon that is provoking him to commit these

offenses. The narrator’s quick change of heart toward the cat seems unjust to the reader

because there is not one incident in his rantings to suggest that the cat is anything other

than a normal, loving black domestic cat. In trying to justify his innocence, the narrator attempts to persuade not only the reader but also himself that he is of sane mind. In

an article that examines the sanity of the narrator, one critic writes, “From the very first

lines of ‘The Black Cat,’ the narrator simultaneously creates doubt about his sanity and

tries to win the reader’s sympathy and convince the reader of his sanity” (Ruffner 4).

In addition, critic Bryan Aubrey points out that this story contains a hint of the

supernatural by the way that the narrator wants the reader to believe each of the events

takes place (35). This either explains how Pluto reappears later on in the story to

torment the narrator, even after the gouging of his eye and death by hanging in the yard,

or it is solid evidence that the narrator does not have a sound mind.

Symbolism is one of the main literary elements the reader sees throughout

“The Black Cat.” Even though each critic may attach a different meaning to each symbol, most critics agree on what these symbols are. The cat, the most obvious symbol in

this story, takes on different meanings depending on the critic and his or her particular

analysis. Some critics, Susan Amper for example, question if there really are two different cats in the story or if the second one is just Pluto all along. Amper poses not only

a good question, but also a good answer to how the white mark could appear on the

chest of Pluto when she states, “The cat was caught in the recent house fire and was

burned; the splotch is simply the grayish-white muscle tissue that would lie exposed

where the flesh has burned away” (482). This explanation not only makes perfect sense,

but it also coincides with the narrator’s claim that the cat is thrown into his burning

21

house by the neighbors in an attempt to wake those within. Poe’s description of the

white splotch as taking the shape of the gallows on the second cat’s chest is seen as the

narrator’s interpretation of his own guilt and fear of conviction for his crimes (483).

Another opinion of Poe’s intentions with “The Black Cat” comes from critic

John Harmon McElroy. He categorizes this tale as a “Comic Design” due to Poe’s use

of “dramatic irony” (101-102). With the murder of his cat Pluto and later on his wife,

the narrator notes that both are concealed in walls of fresh plaster. McElroy argues that

this is not a coincidence and is certainly the evidence regarded by the jury for its

conviction of the narrator’s guilt (103). When admitting to the slaying of the cat Pluto,

the narrator tries to convince the reader that he is not responsible for concealing the cat

in the fresh plaster of the wall above their bed. The plaster is another one of the many

uses of symbolism and irony that foreshadow things to come in this tale of murder. In

describing all of his violent crimes, the narrator is oblivious to the multitude of

discrepancies in his confession. McElroy refers to the ignorance of these inconsistencies as “The Narrator’s Laughable Flaws” because his confession is more damning than

the narrator intends (103). The most idiotic and comical flaw is the narrator’s display

of arrogance when he believes he has committed the perfect murder and flown under

the investigators’ radar. Just as the investigators are leaving and he is about to be cleared

of his crime, the narrator taps on the wall where the body of his dead wife is entombed.

His egotistical need to gloat is what arouses the cat to scream, allowing both the cat and

the wife to get their revenge and ultimately send the narrator to the gallows.

It is widely believed that the narrators in Poe’s short stories are somehow

reflections of Poe himself. In “The Black Cat,” the narrator’s insanity is shown through

his innocent description of the horrific crimes he commits. This is not only apparent

from the beginning of his confession but also at the end when he states, “The guilt of

my dark deed disturbed me but little” (Poe 526). Critic James W. Gargano believes

“that Poe’s narrators possess a character and consciousness distinct from those of their

creator” (43). “The Black Cat” is a confession of violent crimes by a man who displays

no remorse or guilt and cannot realistically be a confession of Poe’s actions. Rumors

of Poe’s psychological instability are certainly due to the numerous biographies, many

of which are exaggerations on the true events of his personal life. It is commonly noted

in many biographies that through Poe’s hard life, he often reinvented himself from time

to time with elaborate tales of his origin and career success. Poe, in his frustrations with

his romantic interests, career, and his life in general, was known to indulge in alcohol,

and this may be the connection between himself and the narrator. In “The Black Cat,”

the narrator makes several references to his use of alcohol and even suggests that it is

one of the contributors to his madness. Ed Piacentino, another critic of “The Black

Cat,” agrees with Gargano and advises readers “to avoid the biographical pitfall of

seeing Poe and the…narrator…” as one in the same (42).

Many critics believe there is a connection between the narrator’s hatred of his

cat Pluto and the abusive treatment of his wife (Aubrey 38). In the story, the narrator

describes his wife as a loving, uncomplaining, and patient woman, but still she is a

recipient of his violence and anger along with Pluto. Because of her unwillingness to

fight back against her husband’s physical abuse and her readiness to continue giving

him love he knows he does not deserve, the narrator grows to despise his wife. The cat

22

and wife both continue to show unconditional love and affection for the narrator, even

though he is physically abusive. With this identical treatment from the cat and wife,

the narrator starts to view them as one in the same, and this is why they are both the victims of his violence. In addition, the guilt the narrator feels for his abusive acts toward his

wife makes him sensitive to her constant remarks about the white mark on the cat’s

chest and its resemblance of the gallows. In Aubrey’s critical essay, he speculates that

these references may actually be the wife’s passive aggressiveness toward her husband’s abuse. Aubrey states, “It is as if she is using her one weapon against him, and

persists in doing so until it produces the desired effect, terrorizing the terrorist” (38).

One critic sees the narrator’s motive for violence in this story as anger regarding his apparent feminine traits. In Ann Bliss’s critical essay on “The Black Cat,” she

argues that the relationship between the cat and the narrator is almost maternal in the

way he nurtures and cares for the cat. The narrator may feel as if his interactions with

the cat consist of traces of femininity and therefore see those interactions as inappropriate (Bliss 96). His attempts to display more masculine traits manifest into increasingly gruesome acts of brutality toward Pluto. Bliss points out that in the story there is

no indication that the narrator has a job or any children, which can support the argument

that he has a sense of failed masculinity because of his inability to meet culturally

determined gender expectations (97). During the time this story is set, it would not be

socially acceptable for a man to be publically gay or to even possess the slight trace of

feminine behavior. If the narrator feels he has any feminine traits or thoughts that he

cannot control, it is believable that this could be a source of his frustration and anger.

Bliss feels that the narrator views the cat as his surrogate child, and by the cat revoking his unconditional love for him, the cat is rejecting his maternal side (97). In this

critic’s interpretation, the cat symbolizes the narrator’s constant reminder of his lack of

masculinity which forces him to commit excessively masculine acts like murdering his

wife (Bliss 98).

In truth, the only one who can reveal what is actually meant by each of the

symbols in “The Black Cat” is Poe himself. Each critic has an in-depth and believable

hypothesis and perception of Poe’s hidden messages through his symbolism and

imagery. However, nearly all critical analysis that pertains to “The Black Cat” views the

cat as the main source of symbolism. Most critics believe Poe uses the cat to provoke

his audience to examine not only the narrator’s tale of murder, but also the psychological

well-being of this storyteller. Through the narrator, Poe uses his expertise in the use of

imagery to allow readers to lose themselves in the horror and graphic detail of the story.

Poe’s craftsmanship in using symbolism and imagery also allow him to capture his

audience and lead them toward finding new and various cryptic meanings each time

they read “The Black Cat.”

23

Works Cited

Amper, Susan. “Untold Story: The Lying Narrator in ‘The Black Cat.’” Studies in Short

Fiction 29.4 (Fall 1992): 475-485. Literary Reference Center. Web. 7 Mar. 2009.

Aubrey, Bryan. “Critical Essay on 'The Black Cat.’” Short Stories for Students. Ed. Ira

Mark Milne. Vol. 26. Detroit: Gale, Cengage Learning, 2008. 35-38. Print.

Bliss, Ann V. “Household Horror: Domestic Masculinity in Poe’s ‘The Black Cat.’”

Explicator 67.2 (Winter 2009): 96-99. Literary Reference Center. Web. 4 Apr.

2009.

Gargano, James W. “Critical Essay on ‘The Black Cat.’” Short Stories for Students. Ed.

Ira Mark Milne. Vol. 26. Detroit: Gale, Cengage Learning, 2008. 42-46. Print.

McElroy, John Harmon. “Comic Design in ‘The Black Cat.’” Readings on The

Short Stories of Edgar Allen Poe. Ed. Hayley Mitchell Haugen. San Diego, CA:

Greenhaven Press, 2001. 101-113. Print.

Piacentino, Ed. “Poe’s ‘The Black Catt’ as Psychobiography: Some Reflections on

the Narratological Dynamics.” Studies in Short Fiction 35.2 (Spring 1998): 153168. Literary Reference Center. Web. 8 Mar. 2009.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Black Cat.” Literature: An Introduction to Reading and Writing.

Ed. Edgar V. Roberts and Henry E. Jacobs. 8th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson

Prentice Hall, 2007. 522-527. Print.

Ruffner, Courtney J., et al. “Intelligence: Genius or Insanity? Tracing Motifs in Poe’s

Madness Tales.” Bloom’s BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe (2002): 43-63. Literary

Reference Center. Web. 7 Mar. 2009.

24

LAUREN MORGAN

What Barbie Dolls Are Made Of

Poet Marge Piercy, an American feminist and activist, writes quite liberally on

topics orbiting the sensitive subject of societal expectations of women. In her two

poems, “Barbie Doll” (1973) and “What Are Big Girls Made Of?” (1997), Piercy allows

satirical bitterness to ooze from her stanzas and haunt her readers. By painting such detailed verbal pictures of her subjects, one may assume that many of the pains and emotions from her poems have once been her own. According to Terry McManus, writer

of a short biography on Piercy, “She did not fit any image of what women were supposed to be like. The Freudianism that permeated educated values in the fifties

labeled her aberrant for her sexuality and ambitions.” Her own personal struggles to meet

gender-based expectations in teen and adult life are reflected throughout her poems, a

tangible pain that adds credibility to her words. While these two poems in particular

focus on separate subjects as well as issues, Piercy amplifies the strains of the pressure

that women endure to meet the ideal physical standards of American

society. She

gives readers a better understanding of the psychological and emotional destruction

these strains triggered by viewing these issues from a more morbid standpoint. She uses

dark humor and sarcasm to defend the women who are the subjects of her poems. In

fact, one of her subjects committed suicide because she was being bullied by peers because of her physical appearance. By comparing these women to well-known manufactured products, using vivid and relative imagery, and using an informal diction

beneath heavily sarcastic tones, Piercy allows readers to feel her anger and truly connect to the meanings and messages behind her words.

By allowing the women in her poems to become equivalent to glorified

manufactured products, Piercy can better demonstrate the confusion that humans face

with the difference between fantasies and reality. In "Barbie Doll," the subject is a girl

hitting puberty, and she is described as a girl who was "Presented dolls that did

pee-pee / and miniature GE stoves and irons / and wee lipsticks the color of cherry

candy" (lines 2-4). These lines indicate that the girl was subjected to feminine normalcy

and should therefore be able to assume the roles of the typical adolescent female when

necessary. It is a mockery of her incapability to do so. She was presented with all the

proper tools, so why hasn't she met the proper expectations? According to literary critic

Casey Evans, her comparison to that of a Barbie doll “reveals the irony of the title.” The

girl in the poem lacks society's definition of beauty, which is made clear when one of

her classmates exclaims that she has “a great big nose and fat legs” (6). When she apologizes countless times for her physical incompetence, and “her good nature [wears]

out like a fan belt,” the girl turns to suicide by means of cutting off the very nose and

legs that earn her so much abuse (15-16). In her casket, she is finally recognized as

“pretty” with her manufactured cosmetics and “turned up putty nose,” a heart-breaking

irony that mocks a reality every woman has understood at some point (23, 21). Evans further states that “[g]irls are ultimately and fatally entrapped by society's narrow definitions

25

of feminine behavior and beauty.” In “What are Big Girls Made Of?” Piercy writes:

a woman is not made of flesh

of bone and sinew

belly and breasts, elbows and liver and toe.

She is manufactured like a sports sedan. (2-5)

This parallelism implies that women no longer possess a simple natural beauty, or even

an internal beauty, but rather a plastic and manufactured beauty that can only be deemed

acceptable by society. The speaker patronizes the subject, Cecile, for improperly wearing “skirts tight to the knees” and “dark red lipstick” in 1968 (13, 12), which apparently was a time in which “mini skirt[s]” and “Lipstick pale as apricot milk” were more

fashionably suited (14-15).

Piercy's comparisons coincide flawlessly with her imagery. While both poems

involve imagery of different degrees, both are abundant in it, and it is this poetic device

that brings her words to life. In “Barbie Doll,” most of her imagery is used at the end

of the poem to exaggerate the girl's funeral, where she is finally labeled as attractive.

Piercy describes:

In the casket displayed on the satin she lay

with the undertaker's cosmetics painted on

a turned- up putty nose,

dressed in a pink and white nightie. (19-22)

This provides a strong visual aid of what the girl looks like in her final “glorious”

moments when she has met society's standards. Piercy’s previously vague descriptions

of the girl are intended to only allow readers to picture the girl's inadequacies. Our

only visual insight is of the girl's overly large nose and legs. Meanwhile, “What Are Big

Girls Made Of?” is much richer in imagery due to the themes of the poem. When the

speaker describes the former college version of Cecile, she uses images of her “[wriggling] through bars like a satin eel,” and “her mouth [pursing] / in the dark red lipstick

of desire” (9-11). When describing French fashion models, she uses loads of satirical

humor. She uses comical images such as “The breasts are stuffed up and out / offered

like apples in a bowl,” (8-9) and the following:

hair like a museum piece, daily

ornamented with ribbons, vases,

grottoes, mountains, frigates in full

sail, balloons, baboons, the fancy

of a hairdresser turned loose. (13-17)

This humor exaggerates the ridiculous measures women not only go through now, but

in earlier times as well, to be accepted by society. She says that the “superior” modern

woman is “thin as a blade of scissors” (44-45) and that she has “a body of rosy / glass

that never wrinkles / never grows, never fades” (50-52). This is a recitation of the

attributes women must obtain to be physically accepted by men and fellow women.

The speaker contrasts the love of humans to that of dogs, by saying that dogs fall in love

just as passionately as we do but with “furry flesh / not hoop skirts or push up bras / rib

removal or liposuction” (61-63) and further questions why we as humans cannot “like

each other raw” and “love ourselves” (67-68). These poems both use intense

imagery to exaggerate the points Piercy's speakers are making, and her word choice further connects the readers to her speakers.

26

The diction Piercy uses for both poems is relatively informal and extremely sarcastic, which is intended to allow readers to further feel these emotions with a

modern viewpoint. If the speaker used an elevated formality, the quality and seriousness of

the poems would, ironically, lose value. Readers feel a personal tie to the poems that

would be missing if any other writing style had been used. For example, in “Barbie

Doll,” Piercy switches back and forth, using words such as “pee-pee” and then “dexterity” (2, 9). This shows the juvenile innocence of the subject as well as her position in

which she was forced to lose that innocence and make a decision that no child should

have to make: whether or not she wants to keep or take her life. Piercy ironically and

satirically describes puberty as magical and then backs this up with evidence that is

anything but. The only thing that changed for the subject once she hit puberty was the attained knowledge of her physical inadequacies and her peers' capabilities to attack her

with such knowledge. Piercy further concludes the poem with everyone exclaiming

how pretty the girl is in her casket and the lines “Consummation at last. / To every

woman a happy ending” (24-25). This is a bitter and facetious ending to a tragic poem.

Piercy uses similar dark humor in “What Are Big Girls Made Of?” When referring to

dogs lacking the curse that humans possess of judging physical attributes in extreme

measures, the speaker uses informal phrasing such as:

they sniff noses. They sniff asses.

They bristle or lick. They fall

in love as often as we do,

as passionately. (57-60)

The modernized speech helps the reader better connect with the poem, while the

simplicity of the words carries heavy meaning. Piercy questions the possibility of a

time in which women will stop viewing their bodies as “science projects,” or “gardens

to be weeded,” or “dogs to be trained”(79-81). On the surface, these analogies do not

have much depth, but their very simplicity makes them so much more tangible. These

daily American images should not depict how women should treat their bodies. The

speaker scorns society for punishing one another for physical deficiencies, whether

controllable or not, saying “as if to have a large ass / were worse than being greedy or

mean?” (76-77). How is it that, in our society, choosing the wrong clothing to wear is

looked down upon more so than being rude or hateful?

Both “Barbie Doll” and “What Are Big Girls Made Of?” reflect on society's

disgusting mistreatment of women lacking the physical attributes Americans deem

appealing. Even with the gap in time between the writing of the two poems, the issues

of physical inadequacies are always present and always deeply impacting. In both of her

poems, Piercy uses heartbreaking comparisons of her subjects to popular manufactured

goods, she uses detailed imagery in order to allow readers to envision the tragic strains

of her subjects, and she uses an informal and satirical diction that further connects the

readers to the speaker. The poems contain the excruciating truths of what women have

always endured when not accepted by society, or in order to be accepted by society, and

to what lengths they may go to escape the condescending hatred of peers. Whether the

escape be plastic surgery or death, both are equal tragedies when used to flee one's self.

27

Works Cited

Evans, Casey Garland. "A Real Woman in a Barbie World." Dalton State. N.p. Spring

2003. Web. 3 Apr. 2010.

McManus, Terry. "Marge Piercy - Biography." Marge Piercy. Marge Piercy. 2005. Web.

3 Apr. 2010.

Piercy, Marge. "Barbie Doll." Literature, Reading, Reacting, Writing. Ed. Laurie G.

Kirszner and Stephen R. Mandell. Compact 7th ed. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage

Learning, 2010. 1048. Print.

---. "What Are Big Girls Made Of?" Poem Hunters. PoemHunter.com. N. d. Web. 3 Apr.

2010.

28

B R YA N G . T R I B B L E

Dante’s Inferno and the Nature of Sin

Dante uses the contrapasso, or counter penalty, as the punishment for sinners

in each of the circles of Hell. Because the contrapasso is somehow related to the sin

committed on Earth “every punishment is an allegory of the evil and unrepentant life

the sufferer actually lived” (Gilbert 74). The punishment is intended to reflect in some

way the damage that is wrought by committing the sin, and it often goes beyond the

damage that is done to the sinner by sinning and also inflicts a punishment that takes

into account the damage inflicted on society and others by carrying out the sinful act.

Three contrapassos that reflect the allegorical and broader nature of the effects of the

sin are those devised for suicides, Simonists and traitors to guests.

Theologians and philosophers who Dante admires, including Aristotle and St.

Thomas Aquinas greatly influenced his work. The contrapasso as divine justice draws

particularly from Aquinas, who believed that justice came through a sort of counterpunishment “since it is just that he who has been too indulgent to his will, should suffer something against his will, for thus will equality be restored” (Aquinas 4636).

In the second ring of the seventh circle of Hell, Dante finds those who have

committed suicide. They have been deprived of their earthly bodies and appear only as

trees; Pier della Vigna, one of the trees, explains to Dante, “We once were men and

now are arid stumps” (XIII.37). The trees are unable to speak except through the blood

that oozes from them when a leaf or branch has been broken off.

Those who commit suicide here are evidently only those who profess Christianity

because other pagan historical figures who have committed suicide, like Cleopatra and

Dido, appear in other parts of the Inferno. The medieval Catholic Church itself strongly

condemned suicide as “an attempt to cut short the term of life allotted by God, a crime

of insubordination against the Creator” (Grandgent 60). This connection with Christianity gives a strong basis for the disembodiment that the sinner suffers since The Bible itself, in I Corinthians 3.17, says that “if any man defile the temple of God, him shall God

destroy.” If “the temple of God” is the body then those who commit suicide are forfeiting the use of that temple by turning it against itself, and they are thus turned into something non-corporeal in Hell as a fitting contrapasso.

This forfeiture of control over one’s self even extends to one’s position in the

second ring of the seventh circle, as explained by della Vigna:

When the savage spirit quits

the body from which it has torn itself,

then Minos sends it to the seventh maw.

It falls into the wood, and there’s no place

to which it is allotted, but wherever

fortune has flung that soul, that is the space

where, even as a grain of spelt, it sprouts. (XIII.93-99)

Finally, the trees can speak only through their blood. This is a fitting punishment

because many who commit suicide are using their death to finally say something about

their internal struggle, often catalogued through a letter left to loved ones. In the after29

life they have been deprived of the ability to speak of their own free will, an ability

which they enjoyed in life on Earth but failed to take advantage of in order to air their

grievances. Now they can only speak after being attacked by the Harpies that fly through

the forest, an act that not only causes them pain but also is entirely beyond their control.

Next, in the third pouch of the eighth circle, Dante finds the Simonists, those

who have sold religious objects or offices for personal gain. The sinners here are found

upside down in burrows likened to a type of medieval baptismal font found in Dante’s

time. Dante indicates that the Simonists make a mockery of their religious office,

“Rapacious ones, who take the things of God, / that ought to be the brides of

Righteousness, / and make them fornicate for gold and silver!” (XIX.2-4). The act is “a

perversion of the holy matrimony conventionally posited between Christ (groom) and

the church (bride)” (Raffa 91).

That the sinners are found upside-down shows that there is a reversal of their

intended role; the Simonists chose to serve their own material needs at the expense of

the spiritual needs of those that they were meant to be serving. By plugging up the

baptismal font they are likened to be in, they are preventing the grace of salvation from

being bestowed upon others, as well as themselves, or, as Dante puts it, “your avarice

afflicts the world: / it tramples on the good, lifts up the wicked” (XIX.104-105).

Finally, in the third ring of the ninth circle, called Ptolomea after one of its

famous inhabitants, Dante finds the traitors to guests. These are sinners who have

betrayed those who accepted an invitation or interacted with the sinner under the

assumption of hospitality and neutrality by murdering them. Dante seems to take

particular exception to these types of sinners because they are immediately condemned

to Hell upon carrying out their sins and prevented from seeking forgiveness and penitence. Though the bodies of these traitors are still alive on Earth, their soul is sent immediately to Hell, and it is replaced by a demon on Earth. In a way, this highlights the

inhumanity of their actions by forcing them to forfeit the thing that makes them most

recognizably human: their human body.

Like all the sinners in this circle, the actions of the traitors to guests are seen

as inhumane and cold-blooded. Allan Gilbert claims, “The sinners in this pit have

departed as far from natural human feelings and obligations as is possible for man”

(109). This cold-blooded nature is reflected in the contrapasso because they all find

themselves encased almost entirely in the frozen waters of the river Cocytus. Everything

about them is made so cold and unforgiving that even their tears, the one method

through which they could grieve for their actions, freeze and seal their eyes shut to

prevent more crying.

Dante effectively uses the contrapasso as punishment to highlight that sins are

eternal. Committing them in life does not simply mean that they are committed and

forgotten; instead, they live on eternally as punishment for the sinner in the afterlife.

And not only is the sinner forced to relive the nature of their sin over and over again

through the contrapasso, they are also made to realize and experience in many instances

the effects their sin has had on others.

30

Works Cited

Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica. Raleigh: Hayes Barton Press, 2006. Print.

Alighieri, Dante. The Inferno. The Norton Anthology of World Literature. Ed. Sarah

Lawall and Maynard Mack. Vol. B. 2nd ed. New York: WW Norton, 2008. 18431870. Print.

The Bible. Print. King James Vers.

Gilbert, Allan H. Dante’s Conception of Justice. New York: AMS Press, 1971. Print.

Grandgent, Charles H. Companion to The Divine Comedy. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press, 1975. Print.

Raffa, Guy. Danteworlds. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2007. Print.

31

P E N N Y D AV I S R I G G S

Looking Down the Tracks

Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” is a short story focusing

on a couple divided by an unwanted pregnancy. The man, who is afraid of losing his

freedom, and a pregnant girl, who faces a decision that threatens their way of life, are

revealed to the reader mostly through dialogue. Hemingway's use of symbolism reveals

the pain and doubt facing the couple's decision. Both characters are seemingly trying

to be well-mannered about the subject of the abortion, which is telling of their relationship and the light-heartedness that has been the main theme until recent events. The

man uses the pet name, “Jig,” as an attempt to get her to soften to him and lead her into

a sense of comfort with him. However, the uncertainties of the abortion, if the girl will

have the baby, and if she will stay with “the American” regardless of her choice, are constantly present and never resolved. The hills, the drinks, and the location of the story