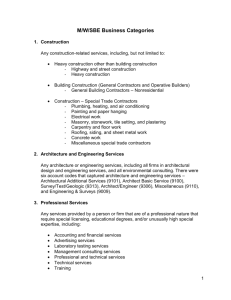

Union Monopoly in Public Works Construction

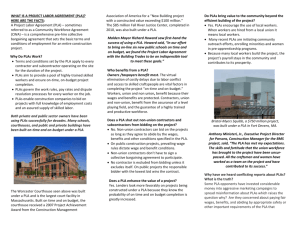

advertisement