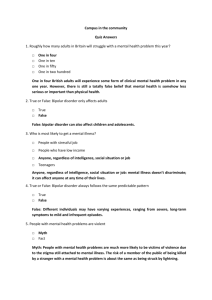

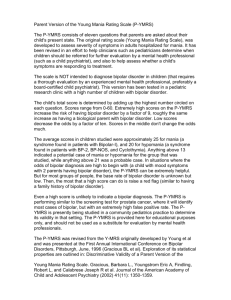

Understanding Bipolar Disorder - British Psychological Society

advertisement