Bipolar Disorder - American Psychiatric Association

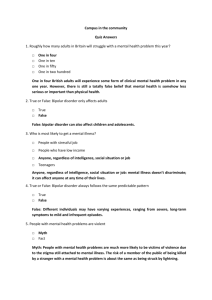

advertisement