Perspectives in Psychology: Substance Use

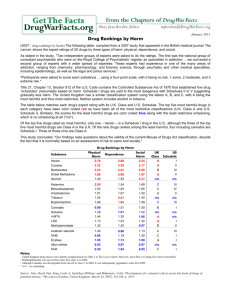

advertisement