Original Paper - Fundació Catalana Síndrome de Down

advertisement

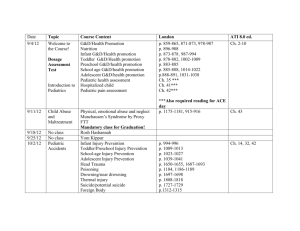

SD-DS 34 INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL ON DOWN SYNDROME 2002: vol. 6, number 3, pp. 34-39 Original Paper Ametropia and strabismus in Down syndrome J. Puig, E. Estrella, A. Galán Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron. Barcelona Correspondence Dr. J. Puig Diagnóstico y Terapéutica Ocular Tuset, 23-25, 3º 3ª 08006 Barcelona Spain Article received on: 19-Feb-02 Translator: Mary Fons Abstract Purpose: To analyze the characteristics of ametropia and strabismus in children with Down syndrome. Patients and methods: A complete eye examination was carried out in 546 children with Down syndrome. Results:Visual acuity was 100/200 or greater in only 21% of eyes examined. Amblyopia was present in 9.7% of children. Mean spherical equivalent was +1.02 diopters; 72% of the eyes were emetropic or hyperopic and 28% were myopic; 17% of the eyes had a negative astigmatism of 2 diopters or greater. Strabismus was found in 240 cases. Only 1.2% had an isolated vertical deviation. Incomitant esotropia was the most frequent finding in this study. Conclusions: Ametropia and strabismus in Down syndrome are different from the general population in frequency, type, low incidence of amblyopia and causes of torticollis. Keywords: Ametropia, Strabismus, Down syndrome, Pediatric ophthalmology Introduction The large number of people with Down syndrome and the diversity of medical conditions associated with it require integrated care to be multidisciplinary and coordinated among different specialists. A higher-than-normal prevalence of eye problems in this patient group has been reported for years; particular issues are extrinsic eye motility (strabismus) and refractive error (myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism) [1, 2, 3]. Thus, a complete eye examination at an early age is required, to detect these conditions and take effective action before the consequences become irreversible. The aim of this paper is to quantify and describe strabismus in a large population of patients with Down syndrome, as well as conditions that may cause it or result from it, such as refractive errors, low visual acuity and amblyopia. Patients and methods A complete eye examination was carried out for 546 patients with Down syndrome, 295 boys and 259 girls, referred to our clinic by Fundació Catalana Síndrome de Down. Their ages ranged from 1 month to 18 years; mean age was 6 years and 5 months, with a standard deviation of 4.65 years. In every case, the examination included extrinsic eye motility, refraction under cycloplegia and ophthalmoscopy. For patients who were old enough and sufficiently cooperative, visual acuity was determined with and without optical correction, along with manifest refraction, binocular vision and biomicroscopy of the anterior pole. Visual acuity was tested with the Teller visual preference test, Pigassou’s optotypes and Snellen’s Eoptotypes, using normal parameters. The protocol for inducing cycloplegia consisted of instilling 0.5% SD-DS 2002: vol. 6, number 3, pp. 34-39 INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL ON DOWN SYNDROME atropine drops (t.i.d. the day before the visit and b.i.d. the day of the visit), or 1% cyclopentolate drops (every half hour, starting two hours before examination). Manifest refraction and refraction values obtained by skiascopy without cycloplegia were never considered adequate. Eye motility was assessed by determining deviation in the primary position, using the Hirschberg corneal light reflex test for near vision, cover test for far and near vision, and prism testing whenever the patient was sufficiently cooperative. The Lang, Titmus and TNO tests were employed for binocular vision. Funduscopy was performed using an indirect ophthalmoscope and 20 D lens. After the first eye examination, follow-up was always recommended at 6-month intervals, or more often when warranted. Results Each of the patients included in this study was seen 1 to 9 times, with a mean follow-up of 54.31 months. Results therefore comprise 2,486 examinations performed on 546 children. We have grouped results under three headings: visual acuity, refraction, and strabismus. a) Visual acuity Reliable visual acuity data were obtained for 401 of 546 patients, that is 73.44%. Only 21% tested above 0.5; 71% tested above 0.2. The difference in visual acuity between the eyes was 0.3 or more in 39 of the 401 children for whom acuity was established. Of these 39 cases, 23 had considerable anisometropia; 11 were attributed to strabismus; the (a) 35 remaining 5 were caused by a unilateral eye condition (cataract, retinopathy, or optic nerve malformation). b) Refraction Refraction values are missing only for 32 cases out of 546, who failed to show up at the scheduled appointment for refractive testing under cycloplegia. Mean refraction for the eyes that were examined was +1.026 4.18 D. In 72% of cases, refraction values were positive or neutral; in other words, the children were either emetropic (no refraction error) or hyperopic; the remaining eyes were myopic, with negative refraction values (28 %). Negative astigmatism at or above 2 diopters was found in 17% of children. A comparison of spherical equivalents in both eyes (adding half the cylinder power to the sphere power, keeping the positive or negative sign) showed a difference of more than 2 diopters (anisometropia) in 24% of patients. Errors of refraction were treated conventionally by prescribing spectacles when refractive error was significant enough to compromise development of eyesight or influence the course of strabismus. Lasik surgery was elected for one of these patients, who had high myopia (-20.75 D spherical equivalent) and deep hearing loss, which were alienating him from his environment, and who was not amenable to optical correction using spectacles or contact lenses. c) Strabismus Extrinsic ocular motility values were obtained for all 546 children. Strabismus was diagnosed in 240 (44%), as follows: (b) Figure. 1. Incomitant strabismus. Note the convergent misalignment of the right eye, each picture at a different angle (A and B). SD-DS 36 INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL ON DOWN SYNDROME (a) 2002: vol. 6, number 3, pp. 34-39 (b) Figure. 2. Intermittent strabismus. Sometimes misalignment is present (A), other times it is absent (B). • Esotropia (convergence of visual axes): 194 (35.5%). • Esotropia with vertical deviation: 23 (4.2%). • Exotropia (divergence of visual axes): 16 (2.9%). • Vertical deviation alone: 7 (1.3%). Esotropia in these children was classified as follows: • Sporadic (highly infrequent, detected only on occasion): 16 (16/217). • Microesotropia (misalignment of less than 5º): 31 (31/217). • Incomitant (angle of deviation varying more than 10º, excluding accommodative esotropia): 44 (44/217) (Fig. 1). • Intermittent (variable angle of misalignment, with a 0º minimum; i.e. deviation was very apparent at some times and non-existent at others, during a single examination or on different days): 69 (69/217). • Comitant (deviation angle did not vary at all, or no more than 10º): 52 (52/217) (Fig. 2). • Accommodative (misalignment was corrected with appropriate hypermetropic spectacles, as long as patient was not made to accommodate): 5 (5/217). Vertical deviations found alongside horizontal deviation were due to: • • • • Superior oblique palsy: 3 (3/23). Superior oblique overaction: 2 (2/23). Inferior oblique overaction: 11 (11/23). Deficient elevation in adduction compatible with Brown syndrome: 7 (7/23). Cases of isolated vertical deviation were due to (Fig. 3): • • • • Elevation palsy: 2 (2/7). Inferior rectus palsy: 1 (1/7). Inferior oblique overaction: 2 (2/7). Superior oblique palsy: 2 (2/7). Out of 240 children with strabismus of any kind, 17 (7.08%) were found to have torticollis secondary to their eye condition (Fig. 4): • Chin-up: 8 (8/17). Head tilt in these cases was either due to A syndrome accompanying esotropia or to nystagmus with null point in downgaze. • Head over one shoulder: 9 (9/17). These were secondary to superior oblique deficiency and, in isolated cases, due to complex nystagmus null points. After careful assessment of each specific case, surgical treatment was proposed for 72 of the 240 patients with strabismus (30%). Non-surgical treatment (monitoring, refractive correction, occlusion, penalization, etc.) was elected for the remainder, owing to a number of circumstances: • Strabismus was sporadic or deviation angle was decreasing. • No misalignment in primary position. • Inadequate data because parents or guardians failed to keep the follow-up schedule. • Very small deviation angle. • Poor prognosis due to other, more problematic eye conditions. • Accommodative strabismus. SD-DS 2002: vol. 6, number 3, pp. 34-39 INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL ON DOWN SYNDROME Figure 3. Deficient elevation of the left eye in adduction. However, only 35 of these patients (48.6%) actually underwent surgery. The reasons varied widely (Fig. 5): • Preference for surgical facilities closer to the child’s home town. • Risk to life due to a concomitant systemic condition. • Economic issues. • Parents opting not to have surgery, having interpreted that the only indication was esthetic, as there could be no guarantee of improved visual acuity or binocular vision. Strabismus surgery for children with Down syndrome was planned according to the same parameters applied for any other child. Outcome was considered satisfactory after a single surgical procedure for 27 of the 35 patients operated. Of the 8 remaining cases, 6 had undercorrected esotropia after surgery; the other 2 had overcorrected esotropia. Four of the patients whose initial outcome was rated as poor underwent further surgery with good results. Down syndrome due to their higher systemic susceptibility. However, topical atropine drops placed on the conjunctiva appear merely to cause the pupils to dilate faster and longer [9, 10]. No significant adverse effect has been recorded, except for occasional flushed faces, just as frequent in other children. Visual acuity was poor in a large number of cases. Although some authors feel that children with Down syndrome have less keen vision as a result of morphological changes in the central nervous system [11], we feel that this is merely attributable to cooperation issues, since acuity testing is subjective and largely depends on children’s responses, and these particular children easily lose interest. However, the fact that a difference in visual acuity of 0.3 or greater was only found in 39 of the children was judged significant. This is a very low rate of medium to severe amblyopia. In 23 cases, the cause was high anisometropia; strabismus was found in only 11 such patients. Considering the fact that children with strabismus who do not have Down syndrome have a 50% rate of amblyopia, and children with microtropia a 90% rate, we wonder why strabismus is less likely to cause amblyopia in children with Down syndrome – might they have a lower capacity for cortical suppression? When we analyze strabismus in these patients, the first striking finding is its high prevalence. The prevalence of strabismus in the general population is 45%, but in this study of children with Down syndrome we found a rate of 44%. Previous studies found similar rates, ranging from 30% to 44% [8, 12]. We note that there is a strong tendency to esotropia, and few cases of vertical deviation associated with horizontal deviation, whereas the latter are very frequent in non-Down-syndrome strabismus patients, who have this association in 90% of congenital cases Discussion This is the long-term ophthalmologic study with the largest population of pediatric Down syndrome patients so far, with a mean follow-up of 5 years. Other published studies used a smaller sample and gave the outcome of a single examination, with no follow-up, or else involved an older population.[4, 5, 6, 7]. Only Haugen and Hovding reported a mean followup of 55 months, on a group of 60 children. [8] Concerning examination methods, many believe that atropine should not be used for children with 37 Figure. 4. Head tilt over the right shoulder. SD-DS 38 INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL ON DOWN SYNDROME (a) 2002: vol. 6, number 3, pp. 34-39 (b) Figure 5. Surgically corrected esotropia: pre-surgery (A) and post-surgery (B). and 25% of acquired cases. Perhaps the reason is, among others, that strabismus tends to be acquired rather than congenital in children with Down syndrome. According to Haugen and Hovding, mean age of onset of strabismus in the group of children with Down syndrome which they studied was 54 6 35 months [8]. The low rate of inferior oblique overaction in association with esotropia, as well as cases of deficient elevation in adduction, cause us to wonder whether it is the shape of the orbit in Down syndrome that is causing this altered oblique muscle function. Only 5 of the children had accommodative strabismus, a very low rate compared to the non-Down population. It is also low compared to a study by Hiles [13], where half of all esotropia cases were accommodative, and all but one were solved with glasses or myotic drops. There are published reports showing diminished accommodative facility in children with Down syndrome [8, 14] The number of intermittent strabismus cases is strikingly high. The potential role of accommodation in these cases was explored, but no correlation with refractive error emerged; neither was misalignment found to be concurrent with accommodative strain. If intermittent noncomitant non-accommodative esotropia is termed “innervational” in children without Down syndrome, we must assume that most cases of esotropia in children with Down syndrome are innervational. Another salient finding is the number of microtropic misalignments (31 microesotropia cases); as mentioned, these misalignments have not caused amblyopia, unlike microtropia in children without Down syndrome. Does this represent a primary incapacity for foveal fusion, causing alternating strabismus? Might such an incapacity be the cause of strabismus in most Down syndrome patients, with or without an innervational component unchecked by fusion amplitude, which in turn would be lacking because of failure to develop proper binocular vision? Children with Down syndrome often have torticollis, or head tilt, all the more frequently the younger they are. It is fostered by generalized hypotonicity and the hyperlaxity of the atlantoaxial joint, but in 17 cases we found the cause of torticollis to be eye-related, caused by either nystagmus null points or oculomotor imbalance. Outcomes of surgery are no different from outcomes in children without Down syndrome, who are more often undercorrected initially. Longer-term follow-up may show late overcorrection, as in the case of non-Down patients with esotropia. References 1. Caputo AR, Wagner RS, Reynolds DR. Down syndrome: clinical review of ocular features. Clin Pediatr 1989; 28:355-8. 2. Shapiro MB, France TD. The ocular features of Down´s syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 99:659-63. 3. Roizen NJ, Mets MB, Blondis TA. Ophthalmic disorders in children with Down syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 1994, 36, 594-600. 4. Merrick J, Koslowe K. Refractive errors and visual anomalies in Down syndrome. Downs Syndr Res Pract 2001; 6:131-3. 5. Wong V, Ho D. Ocular abnormalities in Down syndrome: an analysis of 140 Chinese children. Pediatr Neurol 1997; 16:311-4. SD-DS 2002: vol. 6, number 3, pp. 34-39 INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL ON DOWN SYNDROME 6. Da Cunha RP, Moreira JB. Ocular findings in Down syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1996; 122:236-44. 7. Berk AT, Saatci AO, Ercal MD,Tunc M, Ergin M. Ocular findings in 55 patients with Down´s syndrome Ophthalmic Genet 1996; 17:15-9. 8. Haugen OH, Hovding G. Strabismus and binocular function in children with Down syndrome. A population-based, longitudinal study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2001; 79:133-9. 9. Harris WS, Goodman RM. Hyper-reactivity to atropine in Down´s syndrome. New Eng J Med 1968; 279: 407-10. 10. Priest JH. Atropine response of eyes in mongolism. 11. 12. 13. 14. Am J Dis Child 1960; 100: 869-72. Courage ML, Adams RJ, Reyno S, Poh-Gin Kwa. Visual acuity in infants and children with Down syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 1994; 36:58693. Catalano R A. Down Syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 1990; 34 :385-98. Hiles DA, Doyme SH, Mc Farlane F. Down´s syndrome and strabismus Am. Orthop J 1974; 24 : 63-68. Woodhouse JM, Meades JS, Leat SJ, Saunders KJ. Reduced accommodation in children with Down syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993;34: 2382-7. FUNDACIÓ CATALANA SÍNDROME DE DOWN C/ València, 229 - 08007 BARCELONA, SPAIN I wish to receive SD-DS INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL ON DOWN SYNDROME on a four-monthly, free basis, ONLY BY E-MAIL. In English Spanish 39 Catalan Name: ................................................................................................................................................................................................... Adress: ................................................................................................................................................................................................. Zip/Post Code: ........................... City or Town: ......................................................... Country......................................................... Profession: .................................................................................... Speciality: ...................................................................................... Date:.............................................................................................. E-mail: ........................................................................................... How did you find out about SD-DS?