Psy346-8 Death and dying notes

advertisement

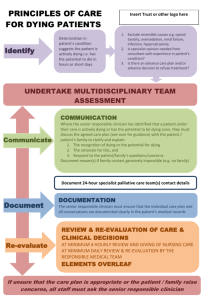

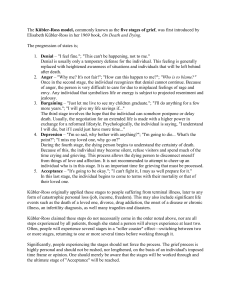

1 Psychology 3460: Dying and Death I. Introduction II. What is death? A. Cultural aspects B. Technological aspects III. The psychology of death A. Death trajectories B. Stages of death C. Social relationships and dying IV. The management of the dying patient A. Hospice alternative V. Grief and bereavement A. Psychological consequences B. Physical health consequences 2 3/26/02 I. Introduction (OVH) II. What is death? Death would seem to be simple to define. But the distinction is a lot more complex than - “you live than you die”. In Western cultures we view death as a biological phenomena, however, other cultures such as the Anggor of New Guinea see death as a magical phenomenon in which sorcery plays a major role. Of course, one’s view of death (e.g., religious beliefs) will impact on how one lives their life and what happens to them once they are dead (e.g., ceremonies). Even within Western cultures, however, our definition of death has changed as we gained more technological sophistication. III. The psychology of dying. When does a person go from living to dying. For health care professionals the criteria is likely to be biomedical. It is important to note that this diagnosis often has important effects on subsequent care as this person may now be viewed differently by health care professionals. Bower and colleagues (1964) found that nurses took longer to answer calls from dying patients than patients whom they expected to recover. Moreover, even after given feedback on this discrepancy, the same pattern returned after a few weeks. For family and friends, the transition from life to dying is more psychological in terms of when such information is accepted. Until relatively recently, the prevalent thinking was that patients should not be told of their death which resulted in a conspiracy of silence. Although it was meant to have a positive effect, it often does the opposite as patients either know or suspect they are dying and the lack of acknowledgement by others may deepen their sense of isolation. Death Trajectories. (OVH) Glaser and Strauss in their pioneering work entitled Time for Dying (1968) described the process of dying in terms of different trajectories. One of the most common is the lingering trajectory, expected quick trajectory, and the unexpected quick trajectory. Death via the lingering trajectory is hard to deal with but sometimes individuals can find solace in the fact that the person’s suffering is over. Death via the unexpected quick trajectory is particularly hard for all to deal with because of its unexpected nature. Stages of dying. (OVH) Elizabeth Kubler-Ross (1969) and her theory of the stages of dying based on her interviews with more than 200 dying patients. According to Kubler-Ross, the first stage in response to the dreaded news appears to be denial. It may serve self-protective functions to give the person more time to deal with the situation psychologically. In fact, it may be helpful if it is only temporary. The second stage is anger as people ask the question “Why me”. The third stage is bargaining in which the person tries to alter the situation by bargaining with a higher entity or medical professionals. When bargaining fails, the person enters the stage of depression as they realize all hope 3 may be lost. Kubler-Ross views depression as being a necessary step towards the final stage of acceptance and advises people to accept the person’s depression, share in the sadness, and when appropriate, offer support and reassurance. I should note, however, that this model appears to simply describe different reactions to dying and not necessarily that people go from one stage to the next in a nice and orderly fashion as other researchers have critiqued. In addition, anxiety appears to be commonly experienced in the dying. Social relationships and the dying. Family and friends may find interactions with the patient difficult. What does one say or do for a dying person? Fortunately, this communication problem can be overcome. (OVH) The key, according to Kastenbaum (1991) is to face fears and emotions directly and communicate as openly and sensitively as possible. It is recommended that one be sensitive to symbolic forms of communication (e.g., hints at topics the patient may want to discuss). Second, it is urged that people help make competent behavior possible for the dying so people can provide support without the patient feeling as if others are taking over. Relatedly, people should allow the dying person to set the pace in activities and discussions . Finally, communication is facilitated when people refrain from projecting their own needs and fear on the dying but should allow the dying to deal with death in their own way. IV. The management of the dying patient. Most people, it turns out, die in hospitals that are uniquely trained to take care of the symptoms of dying and in this way may ease the process. One problem with hospitals, however, is that they are not trained to deal with the psychosocial needs of the patient. Hospice alternative. The hospice movement was originated by British physician Cicely Saunders and has grown out of the concern over the problems of dying at an institution such as a hospital. It attempts to provide a maximally supportive environment for the dying and their loved ones and helps to provide “death with dignity”. The hospice revolves around several basic principles. First is the control of patient pain and discomfort but not so that it interferes with patient communication as this may disrupt their relationships. A second component is on personal caring (e.g., personalize surroundings) and open discussion of death and dying. Finally, it should be noted that care is not sacrificed in a hospice and it is often less expensive than hospitals. V. Grief and bereavement. Once a loved one has passed away, the surviving family and friends are faced with dealing with the immense loss of the person or the process of bereavement. The intense emotional response to bereavement is known as grief. In Western societies, close ones are expected to experience grief and support is readily available from family and friends. However, after a few days or weeks, this support decreases and the bereaved is expected to deal with the loss on their own. The symptoms of grief are so intense, especially for pathological grief that lasts for long periods of time. In fact, bereaved individuals are more likely to die subsequently than age-matched 4 controls. In particular, men show a much higher rate of mortality following bereavement than women. This may be related to health behaviors or that the social networks of married women are larger than married men and these social resources may help during the intensely stressful process. There is also evidence suggesting that those who handle the grief well in their first year are those who made the best long-term recovery. Dealing with death can be particularly difficult for children. Studies suggest children have much of the same feeling and go through a similar process as adults. However, children are much more likely to express their loss through actions (e.g., engaging in activities they used to with person). Perhaps more importantly, however, is the finding that bereaved children can have both short-term and longer-term psychological and behavioral difficulties soon after parental death. Kastenbaum (1991) suggest several ways that parents can help children deal with the difficulties of losing a parent. First, parents need to be good observers and be sensitive to the childs needs and answer questions as they occur (avoid a big tell all). Parents should also provide accurate, direct, and simple explanations . It is better to say that someone is dead than someone has gone away. In general, parents should accept the child’s thoughts and feelings for what they are and provide support as the child works through them.