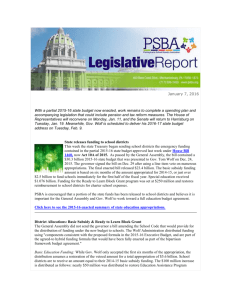

Raising achievement in underperforming schools

advertisement