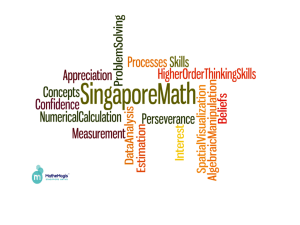

Examining the Role of International Achievement Tests in Education

advertisement