PDF - Fenwick Elliott

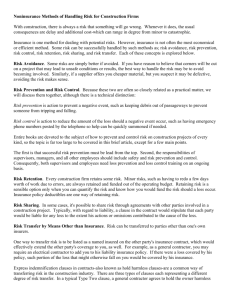

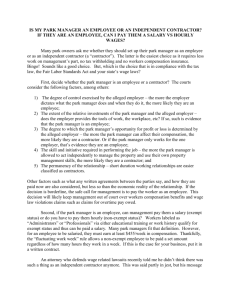

advertisement