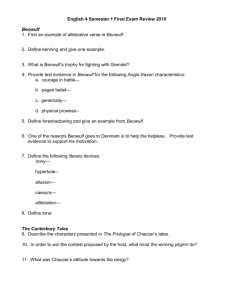

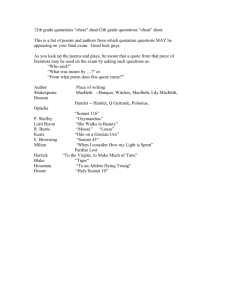

British Literature First Semester Final Exam Study Guide

advertisement