current and emerging issues facing older canadians

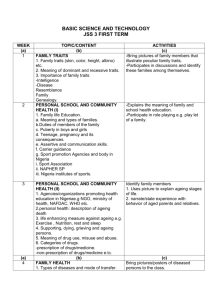

advertisement