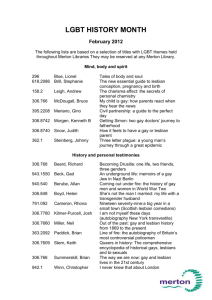

What Changed When the Gay Adoption Ban was Lifted

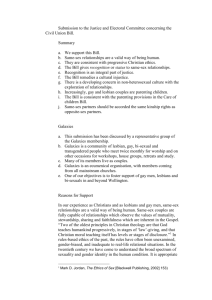

advertisement