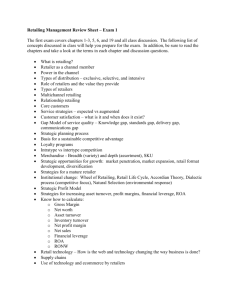

CHAPTER 16 Managing Retailing, Wholesaling, and Logistics

advertisement