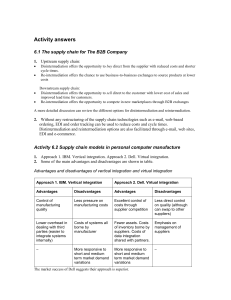

Strategic and Technical Issues in External Systems Integration

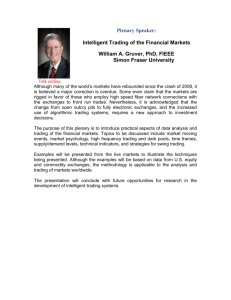

advertisement