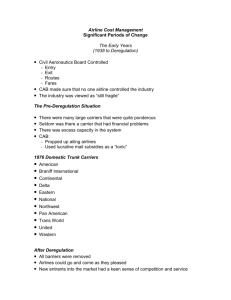

Sales Channels - A Barrier to Entry in the Airline

advertisement