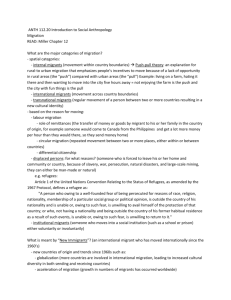

Migration, Health and Cities. Migration, Health and Urbanization

advertisement