Aspin-Brown Report - Amazon Web Services

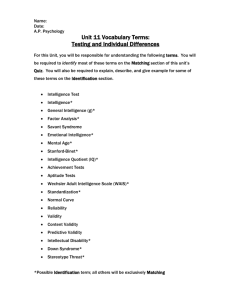

advertisement