Residential Child Care in England, 1948 – 1975: A History And Report

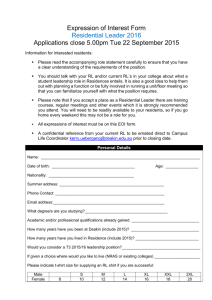

advertisement