Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign

advertisement

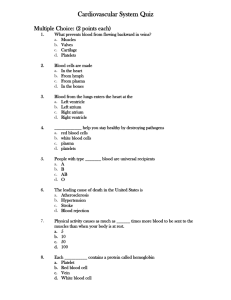

Series on Biomechanics, Vol.27, No. 1-2 (2012), 51- 58 Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign Surfaces R.P. Franke1, F. Jung2 1 2 University of Ulm, ZBMT, Dept. of Biomaterials, Ulm, Germany, Institute for Clinical Hemostasiology and Transfusion Medicine, University of Saarland, Homburg/Saar, Germany, Email: Friedrich.Jung@gkss.de 1. Introduction Surfaces of biomaterials not derived from biological tissues activate the coagulation cascade as well as the complement system when they are exposed to blood e.g. after implantation of cardiovascular implants (e.g. stents, heart valves, occluder systems, vascular grafts) or during procedures like renal haemodialysis. These biomaterials, however, are assumed to be less immunologically active than tissue derived biomaterials [15]. Most proteins involved in the coagulation cascade as well as in the complement system are in precursor forms present in the plasma. For their specific functions, precursor forms have to be activated by either specific cleavage, or by conformational changes, or by both. Blood in contact with artificial surfaces can alterate or even activate the coagulation and complement glycoproteins which is often followed by activation especially of platelets and of leukocytes [20]. The activation of complement was shown to critically raise the susceptibility to infection, pulmonary dysfunction, morbidity, and to effect survival rates of patients with renal failure [12]. Endothelial cells are the key holders of non-thrombogenicity in the blood vasculature. Endothelial cells not activated will generate or present no or only sparse amounts of pro-coagulant proteins like e.g. P-selectin or coagulation-activating factors, at the same time maintaining a sufficiently high level of anti-fibrinolytic activity. Under certain conditions the functionality of endothelial cells can be diminished so that activation especially of thrombocytes and other blood cells, of the coagulation cascade (fibrin generation and polymerization) and of the complement system can occur. One or more of these activating conditions were regularly described in atherosclerotically diseased parts of blood vessels where the endothelial function was demonstrated to be disturbed. So far, in most cases with diseased endothelial cells it could be shown that the endothelial tissue factor pathway inhibitors (TFPI) production was disturbed together with other unbalanced activities of endothelial cells. After application of vascular prostheses the balancing of tissue factor is drastically disturbed primarily because there are no endothelial cells inhabiting the prosthesis, but, secondly because monocytes/macrophages will inhabit the prosthesis wall instead which can release massive amounts of TF. TF is acting both on the activation directly of platelets and the coagulation cascade and at least indirectly on leukocytes. Beside the imbalance of TF due to the lack of EC and the additional local accumulation of monocytes/macrophages there are further influences of body foreign and polymer surfaces especially on thrombogenicity of the blood. Thrombogenicity is still not clearly defined, but at least comprises the activation of platelets and of the coagulation cascade and the generation of thrombi or emboli, respectively. In a very short period of time platelet activation and the so called “contact activation” occur where high molecular weight kininogen (HMWK) and the activated factor XII interact and generate bradykinin. This will further enhance the activation of the coagulation cascade also implying the further activation of the complement system. Several polymer surfaces were reported to have a strong influence on contact activation and in consequence also on the activation of complement and coagulation. A more or less generalized complement activation can have serious consequences due to the reduced removal of antibody complexes which generally need complement decoration for their elimination. And there are more mechanisms to burden the immune system beside the lack of complement. Degradation particles from polymers can become coupled to haptens and lead to immune reactions. 51 R.P. Franke et al./ Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign Surfaces Thrombogenesis with the activation of platelets and of the coagulation cascade can lead to thrombi adhering to the vascular wall in regions with deteriorated endothelial cell function or to emboli which are reaction products of platelets, erythrocytes and the coagulation cascade, which are carried in the blood stream and can lead to the obstruction of supplied blood vessels. So one of the fatal consequences of the generation of thrombi/emboli could be the complete obstruction either of vessels of the heart (myocardial infarction), or of the brain (stroke), or of the lungs (pulmonary embolism). Under certain conditions the vasculature is able to lyse these thrombemboli. This again implies a plasmatic component, plasmin. For the lysis of clots the activation of the plasmin system from plasminogen also needs to be initialized by endothelial cells, via plasminogen activators mainly of the tissue type plasminogen activator (tPA). This is another element of imbalance especially in cases when endothelial cells are lacking. So, not only the generation of thrombemboli can be enhanced (lack of endothelial cell tissue factor inhibitors) but also the lysis of emboli can be strongly decreased (lack of endothelial cell plasminogen activators) in the absence of endothelial cells. And there are not just problems with reduced fibrinolysis, some of the fibrinolytic products can lead to further activation of the plasmatic coagulation. Adding to that, some of these fibrin degradation products where described to be toxic or impeding for other cell species e.g. endothelial cells. Kallikrein-Kinine system Thrombogenicity and coagulation Complement activation Cytotoxicity Opsonisation: Activation of monocytes/ granulocytes (PMN) Fig. 1. Activation sequences and situation in vivo 2. Contact phase activation Within seconds body foreign surfaces will be covered by blood products to varying extent depending on physico-chemical characteristics of the biomaterial surface. Among these are components indicating the activation of the Kallikrein-Kinine system which is also called the contact phase activation [27]. High molecular weight Kininogen (HMWK) is the starting element of Kallikrein-Kinine activity and of vasodilatory effects as well as of the activation of the plasmatic coagulation. It is important to note that negatively charged biomaterial surfaces generally were described to exhibit a strong tendency to activate the contact phase. 52 R.P. Franke et al./ Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign Surfaces Vasodilation Coagulation KK KK PK - HMWK Surface Fig. 2. Contact activation via Kallikrein-Kinine system 3. Complement activation Proteins adsorbing to artificial surfaces usually will be altered in their structure and can be activated as was shown for the two major plasma protein systems, namely the complement system and the coagulation cascade. While it is possible, to control coagulation using anticoagulants, there are no clinical agents available to prevent activation of complement on the contact of blood with biomaterial surfaces. Of the three described pathways of complement activation, the classical pathway of complement activation (CP) is usually started by binding of antigen-antibody complexes to C1q (complement-fixing antibodies), leading to formation of C1r, C1s, C4, C2, C3 and C5. An antibody independent activation, called lectin pathway (LP), was found in which the C-type lectin domain present in mannose binding lectin (MBL) together with MBL-associated serine-protease (MASP) bound to mannose or N-acetylglycosamine structures. The alternative pathway (AP) usually will become activated slowly and spontaneously by a change of C3conformation upon adsorption and hydrolysis of the internal C3 thioester bond [29, 16] and will further be enhanced by C3 contact with body foreign surfaces [34]. In AP activation on cell surfaces, C3b was found to bind covalently to hydroxyl or amino groups [16], whereas in AP activation on body foreign surfaces C3b binding occurred when no hydroxyl or amino groups were available [15]. Body foreign polymeric surfaces will initially trigger limited CP activation followed by C3b binding and AP amplification where most of the effect is determined by AP amplification [3, 16]. Nascent C3b will bind covalently with the thioesterbond to surface components forming CP clusters, then will bind factor B and factor D and properdin, resulting in stabilisation of C3 convertases and in additional amplification [11]. In plasma there is a spontaneous hydrolysis of C3 occurring continuously as part of AP, denominated as “tickover”. The three pathways meet together in the formation of two C3 convertases (C3Bb and C4bC2a) and two C5 convertases (C3bBbC3b and C4bC2aC3b) implying cleavage of C2 and C4 (CP and LP) or the serine proteases factor B and factor D (AP). Subsequently, the anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a, the opsonins C3b and C4b and the membrane attack complex (MAC; C5b-C6-C7-C8-C9 abbreviated as C5b-C9) are generated. C5b was shown to induce P-selectin expression on platelets [36]. The C5b-C9 complex can also play a role in the activation of platelets [17]. The blockade of the C5b-C9 complex was demonstrated to prevent platelet activation [31]. Deposition of C3b/C4b on pathogens or body foreign material lead either to ingestion by phagocytic cells (opsonisation) or to their lysis by interaction with the MAC, termed as lytic mechanism. Factor H is a potent soluble inhibitor of AP serving as cofactor for factor I in conversion of active C3b to inactive iC3b. With a broad variety of complement activation stimulators or inhibitors existing [11] there can be many and very different reasons why a body foreign surface could appear as compatible or incompatible. E.g. Factor H could specifically bind to such a surface and be available for the down regulation of C3 activation or, conversely, factor B could bind to such a surface and be available for further AP activation. The complement system is assumed to act as an instructor of the humoral immune response in 53 R.P. Franke et al./ Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign Surfaces Cell lysis Cell Cell stimulation stimulation TH2 (Mo, (Mo, PMN, PMN,TTH1 H,1, TH, 2, regT) regT) TCC C5a C3a C5 C9 C5 Alternative pathway (AP) on cell surfaces C3 OH NH2 cell surface Fig. 2a. Complement activation on cell surfaces Cell lysis Cell Cell stimulation stimulation (Mo, TH2 H,1, TH, 2, regT) (Mo, PMN, PMN,TTH1 regT) TCC C5a C3a C5 C9 C5 C3 OH C1q 2: Alternative pathway amplification 1: Limited Classical pathway Body foreign surface Fig. 2b. Complement activation on body foreign surfaces lowering the threshold for B-cell activation and promoting optimal B-cell memory [8]. Complement can also modulate T-cell responses [9] in all phases of immunological activity either through direct modulation of Tcells themselves or indirectly through alteration of antigen presenting cells (APC) [21]. Some of the complement activation products act as mediators of inflammation. They can bind to specific receptors on polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN), monocytes, macrophages, and e.g. mast cells. Binding in already adherent cells can induce e.g. release of oxidative products and/or lysosomal enzymes. Monocytes can be induced by C3a to generate cytokines. Activation of complement in the presence of polymer based biomaterials is assumed to proceed most likely through limited CP activation followed by massive alternative pathway amplification. However, contact of blood with negatively charged surfaces seems to activate complement via the classical pathway. 4. Activation of platelets and of the plasmatic coagulation The main function of platelets is the formation of mechanical plugs at vessel wall injuries, following 54 R.P. Franke et al./ Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign Surfaces platelet activation. Therefore, the platelet surface has various receptors and there are different stimuli, which activate platelets, with diverse platelet responses to these stimuli, mediated by the binding of various stimulants to specific platelet receptors. Fig. 3. Platelet thrombus growing on a stent strut in a closed loop in vitro system perfused with platelet rich plasma During the early phase of adhesion (tethering phase) the platelet responses are reversible [32], which include adhesion, shape change and reversible aggregation. When platelets adhere, they change their shape from discoid to spherical with the extrusion of the pseudopods [18, 37]. There is a suggestion that the procoagulant activity and subsequent production of thrombin increases on the platelet surface due to this platelet shape change [10]. Platelet adhesion occurs in flowing blood and it has to withstand the shear stress exerted by the haemodynamics of the blood flow [19]. Platelets not only adhere to injured vessels walls but also to particulate matter in the blood stream, bacteria and other microorganisms, macrophages and to the artificial surfaces of prosthetic devices [28] Apparently, the only surface at which platelets do not adhere seems to be the surface of non-activated endothelial cells. The release reaction, which augments the platelet aggregation, is regulated by two positive feedback loops. Firstly, endoperoxides like thromboxane A2 and ADP, which are released during the reaction provoke by intracellular mechanisms further expression of the fibrinogen receptors on the platelet surface, thus inducing further platelet aggregation [14]. Secondly, the synergism between the different platelet agonists augments platelet aggregation [2, 4, 6]. Full platelet aggregation can also be induced by the simultaneous addition of subthreshold levels of platelet stimuli, which fail to induce platelet aggregation on their own merit. The linking of the platelets via fibrinogen brings about platelet aggregation. A great number of agents (including ADP, epinephrine, collagen and thrombin) can induce platelet aggregation [22]. Simplistically, vWF and fibrinogen bind to receptors on one platelet and create crosslinks to another platelet by binding to receptors on the latter [25]. Activated platelets contribute to haemostasis and it is generally believed that these activities are relevant to thrombus growth, where the bulk of the thrombus often seems to be a mass of platelets. Platelet membrane phospholipids potentiate the intrinsic pathway of coagulation, which eventually forms thrombin from prothrombin by activated factor X [13]. The platelet surface also protects active coagulation factors from inactivation by their natural inhibitors [35]. The release products of platelets play an important role in the formation of platelet thrombi. For example, Platelet Factor 4 seems to possess antiheparin activity, 55 R.P. Franke et al./ Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign Surfaces and release of fibrinogen could potentially contribute further to the formation of the thrombus [38]. As mentioned previously, P-selectin expression could result in platelet–leukocyte interaction leading to fibrin deposition to stabilize the thrombus [30]. In addition, there has been more evidence on the role of procoagulant activity of platelets. For example, coagulation Factor V located in the alpha granules of the platelets becomes membrane bound when activated simultaneously with two agonists, thrombin and convulsin, an activator of the collagen receptor glycoprotein VI [1]. These platelets are referred to as convulsin and thrombin induced Factor V platelets. These convulsin and thrombin activated platelets were capable of generating more prothrombinase activity than any other physiological agent and thus exhibited much stronger procoagulant activity. Factor V could also be expressed on the platelet membrane by simultaneous activation with thrombin and most of the subtypes of collagen, as would be expected at sites of endothelial damage. A spontaneously formed primary platelet plug is unstable. But the formation of a platelet thrombus is accompanied by the generation of thrombin, which results in the generation of fibrin required for the stabilization of the thrombus [26]. Platelet plug formation and coagulation are closely linked processes. The activation of the plasmatic coagulation can be triggered by different mechanisms: 1: thrombogenic body foreign surfaces induce the contact activation (via FXI, FXII, pre-kallikrein and HMW-kininogen). 2: the vessel wall injury during an implantation procedure leads to the liberation of unbalanced tissue factor that together with FVIIa activates the extrinsic coagulation cascade. In addition, sub-endothelial structures - like collagen, laminin or vWF – activate the so-called surface-sensible coagulation factors (e. g. FXI und FXII). Both mechanisms lead to the activation of the prothrombinase complex and to the transformation of fibrinogen to fibrin and subsequent polymerisation. 3: in consequence of platelet aggregation (activation via FXIIa and FXII-subunits) as well as of fibrinolysis – effected by plasmin - a complement activation can occur (with a feedback loop into the contact activation). 4: Activated platelets release platelet factor 4. This factor can neutralize heparin and acts prothrombotic via the inactivation of heparin. The thrombus stabilisation by the polymerisation and subsequent cross-linking of fibrin under the influence of FXIII is a very complex process with numerous feed-back loops. 5. Determinants of thrombogenicity of cardiovascular implants It has been shown repeatedly that cell adhesion to an artificial material depends strongly on the physico-chemical properties of the material surface, e.g. its roughness, chemical composition, energy, polarity and wettability. The chemical composition of the material surface is an important factor determining the surface energy, polarity, wettability and zeta potential, and consequently the character of the cell–material interaction [5]. Surface roughness influences the platelet adhesion, not only but also, because an increase in surface roughness means also an increase in surface area, where surfaces with greater roughness induce platelet adherence much stronger then smoother surfaces [7]. Surface wettability, described as hydrophilic (“wettable”) or hydrophobic (“non wettable”) is also discussed to be essential. Very hydrophilic surfaces either prevent the adsorption of proteins, or bind these molecules very weakly, prevent also cell attachment and spreading partially or completely. Such surfaces are known to adsorb cell adhesion-mediating molecules relatively weakly, which could lead to the detachment of these molecules especially at later culture periods, when they contain larger numbers of adherent cells. However, optimal cell adhesion was described for moderately hydrophilic surfaces. Tamada et al. [33] claimed that a polymer surface with a water contact angle of 70 o seemed to be the most appropriate surface for cell adhesion, while Lee [24] found a contact angle of 55 o as most appropriate for another polymer. Synthetic polymers used in biotechnologies and in medicine are usually too hydrophobic in their pristine and unmodified state (a water drop contact angle of about 100° or more), so they cannot grant sufficient cellular colonization. The intimal blood vessel layer (vessel intima) is mostly negatively charged against the external blood vessel layer (adventitia of the blood vessel; 1-5 mV) due to the negative charge of polysaccharides of the glykocalyx of the vessel intima. Since blood cells and platelets are also negatively charged, they are usually repelled from the vessel intima. The electrical charge of the material surface is also an important factor for its 56 R.P. Franke et al./ Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign Surfaces colonization with cells. It has been shown repeatedly that there is better cell adhesion to positively charged surfaces than to negatively charged surfaces. A result that possibly depends on the fact, that negatively charged surfaces were shown to activate the complement system. At present, there is no theory which allows to predict the haemocompatibility of a new material. References [1] Alberio L, Safa O, Clemetson KJ, Esmon CT, Dale GL., 2000. Surface expression and functional characterisation of alphagranule factor V in human platelets: effects of ionophore A23187, thrombin, collagen and convulsin. Blood 95, 1694–702. [2] Altman, R., Scazziota A, Rouvier J, Cacchione R., 1986. Synergistic actions of PAF acether and sodium arachidonate in human platelet aggregation. Studies in normal human platelet rich plasma. Thromb Res 43, 103–11. [3] Andersson, J., Ekdahl KN, Lambris JD, Nilsson B., 2005. Binding of C3 fragments on top of adsorbed plasma proteins during complement activation on a model biomaterial surface. Biomaterials 26, 1477 – 1485. [4] Ardlie NG, Bell LK, McGuiness JA., 1987. Synergistic potentiation by epinephrine of collagen or thrombin-induced calcium mobilization in human platelets. Thromb Res 46, 519–26. [5] Bacakova L, Filova E, Parizek M, Ruml T, Svorcik V.,2011. Modulation of cell adhesion, proliferation and differentiation on materials designed for body implants. Biotechnology Advances 29, 739–767. [6] Bushfield M, Mcnicol MA, Macintyre DE., 1987. Possible mechanisms of the potentiation of blood platelet activation by adrenaline. Biochem J 241, 671–6. [7] Braune S, Lange M, Richau K, Lützow K, Weigel T, Jung F, and Lendlein A., 2010. Interaction of thrombocytes with poly(ether imide): The influence of processing, Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 46, 239-50. [8] Carroll M.C., 2004. The complement system in B-cell regulation. Mol Immunol 41, 141 – 146. [9] Dempsey PW, Allison ME, Akkaraju S, Goodnow CC, Fearon DT., 1996. C3d of complement as a molecular adjuvant: bridging innate and acquired immunity. Science 271, 348 – 350. [10] Ehrman M, Tooth ME, Frojmovic M., 1978. A platelet procoagulant activity associated with platelet shape change. J Lab Clin Med 92, 393–401. [11] Harboe M, Hollness TE., 2008. The alternative complement pathway revisited. J Cell Mol Med 12, 1074 – 1084. [12] Hakim RM., 1993. Clinical implications of hemodialysis membrane biocompatibility. Kidney Int 44, 484 – 494. [13] Hemker HC, van Rijn JL, Rosing J. et al., 1983. Platelet membrane involvement in blood coagulation. Blood Cells 9, 303–17. [14] Holmsen H., 1977. Prostaglandin, endoperoxide-thromboxane synthesis and dense granule secretion as positive feedback loops in the propagation of platelet responses during the ‘basic platelet reaction’. Thromb Haemost 38, 1030– 41. [15] Janatova J., 2000. Activation and control of complement, inflammation, and infection associated with the use of biomedical polymers. ASAIO Journal, S53 – S62. [16] Janatova J, Cheung AK, Parker C.J., 1991. Biomedical polymers differ in their capacity to activate complement. Complement Inflammation 8, 61 – 69. [17] Janatova J, Bernshaw NJ., 1998. Complement interaction with biomaterials. Mol Immunol 35, 361. [18] Jung F, Mrowietz C, Seyfert UT, Grewe R, Franke RP, 2003. Influence of the direct NO-donor SIN-1 on the interaction between platelets and stainless steel stents under dynamic conditions. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 28, 2003, 189-199. [19] Jung F, Wischke C, Lendlein A., 2010. Degradable, multifunctional cardiovascular implants: challenges and hurdles. MRS Bull 35, 607 – 613. [20] Kazatchine MD, Carreno MP., 1988. Activation of the complement system at the interface between blood and artificial surfaces. Biomaterials 9, 30 – 35. [21] Kemper C, et al., 2003. Activation of human CD4 cells with CD3 and CD46 induces a T-regulatory cell1 phenotype. Nature 421, 388 – 392. [22] Kinlough-Rathbone RL, Mustard JF, Packham MA et al. Properties of washed human platelets. Thromb Haemost 37 (1977), 291–308. [23] Kemper C, Atkinson P.,2007. T-cell regulation with complements from innate immunity. Nature Reviews/Immunology 7, 9 – 18. [24] Lee JH, Khang G, Lee JW, Lee HB., 1998. Interaction of different types of cells on polymer surfaces with wettability gradient. J Colloid Interface Sci, 205:323–30. [25] McManama G, Lindon JN, Kloczewiak M et al.,1986. Platelet aggregation by fibrinogen polymers crosslinked across the E domain. Blood 68, 363–71. [26] Mann KG, Nesheim ME, Church WR, Haley P, Krishnawamy S., 1990. Surface dependent reactions of the vitamin K dependent enzyme complexes. Blood 76, 1-16. 57 R.P. Franke et al./ Interaction of Blood Components and Blood Cells with Body Foreign Surfaces [27] Matata BM, Coutney, JM Lowe GDO, 1994. Contact activation with haemodialysis membranes. Int J Artif Organs 17, 432. [28] Packham MA, Mustard JF., 1984. Platelet adhesion. Prog Hemost Thromb 7, 211–88. [29] Pangburn MK, Müller-Eberhard HJ., 1980. Relation of putative thioesterbond in C3 to activation of the alternative pathway and the binding of C3b to biological targets of complement. J Exp med 152, 1102 – 1114. [30] Palabrica T, Lobb R, Furie BC et al., 1992. Leukocyte accumulation promoting fibrin deposition is mediated in vivo by P-selectin on adherent platelets. Nature 359, 848–51. [31] Rinder C.S, Rinder HM, Smith BR et al., 1995. Blockade of C5a and C5-C9 generation inhibits leukocyte and platelet activation during extracorporeal circulation. J Clin Invest 96 , 1564 – 1572. [32] Sixma JJ, Hindriks G, Van Breugel H et al., 1991. Vessel wall proteins adhesive for platelets. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 3, 17–26. [33] Tamada Y, Ikada Y., 1993. Effect of preadsorbed proteins on cell adhesion to polymer surfaces. J Colloid Interface Sci 155:334–9. [34] Walport MJ., 2001. Complement. First of 2 parts. New Eng J Med 344, 1058 – 1066. [35] Walsh PN, Biggs R., 1972. The role of platelets in intrinsic factor-Xa formation. Br J Haematol 22, 743–60. [36] Wiedmer T, Sims P., 1991. Participation of protein kinases in complement C5b-C9 induced shedding of platelet plasma membrane vesicles. Blood 78, 2880 – 2886. [37] White JG., 1974. Shape change. Thromb Diath Haemorrh 60,159–71. [38] White A.M., Heptinstall S., 1978. Contribution of platelets to thrombus formation. Br Med Bull 34, 123–8. 58