the nature of ee cumm/ngs' sonnet forms a quantitative approach

advertisement

THE NATURE OF E.E. CUMM/NGS' SONNET FORMS

A QUANTITATIVE APPROACH

That E. E. Cummings favored the sonnet form is amply attested by

the number and variety of sonnets he wrote throughout his poetic

career. Sonnets compose forty percent (61 of 150 poems) of this

first manuscript, Tulips and Chimneys (1922), and nearly twentyeight percent (212 of 770 poems) of his canon. Precisely what

Cummings, whose name is synonymous with radical treatment of and

experimentation with such basic poetic elements as prosody and syntax, has done within the restrictive framework of the conventional

sonnet form has been an intriguing and unsettled scholarly question. 1

ln order to answer this question 1 composed a quantitative content

analysis in which 1 adapted methods common to political scientists

and used the Statitical Package for the Social Sciences 2 as a source

of relevant programs. First 1 artificially differentiated between

seventy-six separate variables and then used the SPSS CODEBOOK

program to set up the data.

Deciding which of Cummings' poems are sonnets was not always a

simple task. Cummings can so vary the linear arrangement, seemingly

use free verse, and focus on unlikely topics in a verbal jargon which

actually disguises the form. For the purpose of this paper 1 will

define a sonnet as a fourteen-line lyric poem, written in iambic

pentameter and having four emanations : ltalian, whose stanzas break

-29-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

into an octave and sestet with an accompanying poetic turn and threeto-five interlocking rhymes; English, with three quatrains and a couplet

according to shift in rhymes, spacing, and poetic turn; Combined, a

variation using features of the two previous forms; and lrregu/ar, an

experimental version with an unconventional rhyme scheme, stanza

spacing, and/or poetic turn. Diagram 1 further delineates the dichotomy between traditional and experimental poetic elements as 1 will

elucidate them in Cummings' sonnets.

ln the following discussion 1 intend first to illustrate the coding of

a representative sonnet and then to give a general sense of how

Cummings innovated within his 212 sonnets : to explain which

traditional aspects he retained, which he reereated anew, and which

he discarded in preference to a new mode of poetic expression.

The actual coding process demanded strict adherence to a detailled

codebook and consistent judgment in the evaluation of variable

values, as this example demonstrates. ldentified as number 143 (see

figure 1 ), "pity this busy monster, manunkind," was included within

the 1944 volume 1 x 1 [One Times One] (TIME = 44). lts meter

is predominantly iambic pentameter; as a result, we find no metric

alternatives (METER, METVAR each = 0). lambic variations include

initial hard word or syllabe, trochaic/iambic tension and reversai,

short lines of three-to-four feet, anapests and dactyls (IAMBVAR

08). ln rhyme, sonnet 143 continues to evince semi-irregularity.

lt comprises both rh y me and not rhyme ( R 1ME = 2). We can

type those rhymes which do appear as rhyme approximate in sound

-30-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

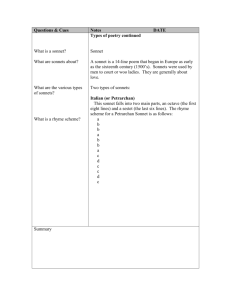

DIAGRAM 1

TRADITIONAL AND EXPERIMENTAL CONCEPTS OF

THE SONNET PARADIGM (ACCORDING TO SPECIFIC

POETIC ELEMENT)

Element

Experimental Concept

Form

Jtalian, English, Combined

(by rhyme scheme, poetic

turn, and stanza _spacing)

lrregular

Content

Love-oriented, womanfocused, reflective of

persona's introspection

Topics other than love,

Jess concern for women,

Jess emotional poet

Language

Romantic, neutra!,

mixed

Satiric, neutra!, mixed

Prosody

Regularity in rhythm,

imagery, specifie deviees;

majority iambic pentameter,

exact rhyme

lrregular rhythm, slant or

half rhyme, few deviees,

Linguistics

c:..,

.....

Traditional Concept

Normal grammar, syntax,

semantics, punctuation, and

typography

experimental meter

Eccentric but recognizable

expression and visual

appearance

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

and/or accent and exact rhyme rather than identical or echoed rhyme

(RIMEAS, RIMEAA, RIMEEX each = 0; RIMEIDEN, RIMEECHO

each = 1 ). The rhymes scheme into an amorphous grouping--abacda

edecfgfg (RIMESCH = 117)--which has poetic turns coming within

the eighth and twelfth lines (BREAK = 63).

Spatially this sonnet is divided experimentally into eight unequal

units ( SPACE = 3). Consequently. its formai classification as lrregular is apt (FORM = 4).

More traditionally, sonnet 143 does have a firm sense of rhythm

(RHYTHM = 0). The sonnet is a satire, as its social message, mixed

neutral and satiric language, and burlesque tone underline (GENRE,

THE ME each = 01; LANG = 5; TONE = 06). Moreover, of the nine

poetic deviees which 1 selected to study--symbol, alliteration, assonance, personification, apostrophe, paradox, oxymoron, wordplay,

and both implied and stated comparisons--only two, oxymoron and

wordplay, remain unused (SYM, ALLIT, ASSON, PERSON, APOS,

PARA, WORDPLAY each = 0; OXY = 1; META = 3). The sonnet

also embodies comparisons to celestial bodies and natural phenomena

(NATURE = 12).

We continue to see this superimposing of traditional upon experimental elements in both imagery and typography. Sonnet 143 uses

Cummings' unique "verbal" imagery, which incorporates syntax and

language for effect rather than function. Too, the poet focuses on

an impersonal adult and his own persona rather than a woman

-32-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

FIGURE 1

SONNET 143 AND ITS CODE

/U

U

/U

1

1

U

1

V

a

pity this busy monster, manunkind,

1

1

not.

ut

/u;v

ulu

Progress is a comfortable disease :

u

lU

1

u

1uLit

1

your victim (death and life safely beyond)

1

U

lulU

Li

u

1

u

lU 1

1

LI

1

1

1

V

1

U

1

U

into a mountainrange; lenses extend

1

u 1

v

1

l)

1

u

v 1

unwish through curving wherewhen till unwish

v 1

u v 1 u

returns on its unself. u

u

1

1

A world of made

1

UfU

V

1

f

lu

1

is not a world of born--pity poor flesh

lJ

1

1

1

u

1

u

1 v

(1

and trees, poor stars and stones, but never this

/UU

1

/U/VU

V

ulu

ultraomnipotence.

U

1

U

1

U

IUU

1

/

1

d

e

c

U

g

f

a hopeless case if--listen : there's a hell

UUI

e

1

We doctors know

lU

a

f

fine specimen of hypermagical

tuuluu

c

d

--electrons deify one razorblade

UIV

a

IV{

plays with the bigness of his littleness

u

b

f

113

of a good universe next door; let's go

g

143 44 0 08 0 2 117 4 0 0 0 1 1 0 01 5 06 4 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0

3 12 8 0 1 1 2 1 1 1 29 06 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 01 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 1 2 0 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 1 1 63

-33-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

(IMAGE = 4; PEOPLE = 8; WOMEN = 0). On the other hand, the

visual appearance is only slightly unconventional; that is, of the

typographically experimental variables--spacing, pictorialism, irony,

and line integrity--only one applies : there is one instance of irregular

linear level (TYIRLINE = 2; TYSPACED, TYPO, TYSEEBE, TYIRONY

each = 1).

Both semantically and grammatically sonnet 143 is basically normal

with few variations (SEMANTX, G RAMMAR each = 1 ). Cummings

created new words by adding the prefix "un-," compounding or

hyphenating pre-existing words, and substituting pronouns or substantives for an unidentified noun. Contrarily, the sonnet does not

include altered denotations; in sorne cases the meaning is only made

ambiguous because of the unreferenced pronouns or substantives

(NEWWORDS = 29; NEWMEAN = 06). Grammatically there is

word mixing, but not word dismemberment. More regularity arises

in the lack of run-on lines, run-on interrupters, sentence fragments,

and juxtaposed accented words (WORDMIX = 0, WORDDISM,

RUNONL, RUNONI, SENTFRAG, HEAVY each = 1 ).

Likewise, the punctuation and capitalization which we encounter

within this sonnet are conventional; normal punctuation delimits

phrases (PUNC = 0; LINFRAS = 1 ). Only the standard deviations

discovered in most of Cummings'sonnets--no ending punctuation or

initial capitalization--are found here (IREND, IRSTART each = 0).

Otherwise, we notice irregularity neither between words or parts of

words nor in the usage of the period, comma, semicolon, colon,

-34-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

question mark, exclamation point, parenthesis, dash, hyphen, ellipsis

or quotation marks. Capitalization of common words, noncapitalization of proper nouns, rhetorical capitalization, and rhetorical

punctuation do not appear (PUNCI RW, PUNCI RS, CAPCOM, NOCAPPRO, RHETCAP, RHETPUNC, IRPERIOD, IRCOMMA, IRSEM,

IRCOLON, IROUPT, IREXCLAM, IRPAREN, IRDASH, IRHYPHEN,

ELLIPSIS, 1ROUOTE each = 1). Parentheses are, however, used as

a qualifier or contributer of additional information (PARENS = 3).

Finally, the syntax of sonnet 143 demonstrates minor departures from

standard use of parts of speech, but not from normal sentence structure (SYNTAX = 1; IRSENSTR = 2). A noun is formed by syntactic dislocation, but not an adjective, adverb, or verb (SYND ISN = 0;

SYNDISAJ, SYNDISAV, SYNDISVB each = 1).

Tables 1 and Il depict, in an abbreviated form, the results of the

computer analysis. Table 1 lists the higher percentage of either traditional or experimental sonnets which use the prosodie and linguistic

characteristics, while table Il delineates percentage inclusion of content

variables. ln sorne cases, wl-ere a variable such as NEWWORDS

involved multiple irregular values, 1 recoded it into a simple dichotomy of traditional and experimental groupings.

-35-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

General overview

Our examination of the first table, like our coding of the typical

sonnet, demonstrates that Cummings was overwhelmingly experimental or traditional only in some areas. The prosody of his sonnets

shows nearly as much regularity as irregularity. Sixty-four percent

of the sonnets have experimental meter and metric variations; less

than 0.5 percent of the sonnets are without iambic variations. Further

poetic license can be seen in the preponderance of irregular poetic

turns, stanza spacing, and rhythm; slant rhyme , that approximate

in sound and/or accent; and common, but unused, sonnet deviees

such as symbol, personification, apostrophe, paradox, oxymoron, and

wordplay. On the other hand, Cùmmings was traditional in his use

of exact rhyme, at the same time as he excluded echoed and identical rhyme; his choice of ltalian, English, and Combined forms; general imagery; and use of alliteration, assonance, and metaphor/simile.

Linguistically and identical pattern of partial regularity and semiirregularity appears.

Ninety-one percent of ali sonnets evince some

experimental vocabulary, whether through the creation of new words,

new meanings, or 'bath modes.

Nearly 92 percent also have abnormal

syntax, which frequently takes the form of irregular sentence structure, including run-on lines and run-on interrupters, more often than

sentence fragments, juxtaposed accented words, or syntactic dislocation to form nouns, adjectives, adverbs, or verbs, although these

three experimental methods do occur.

-36·

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

Another preponderantly irregular variable is general punctuation,

which shows 84 percent variance. Most frequently there is punctuation irregularity between words, no ending punctuation, no initial

punctuation, rhetorical punctuation, linear phrasing, and use of

parentheses. The remainder of the innovative punctuation variables

demonstrate only a slight instance of occurrence. Yet, the mere

fact that they appear at ali suggests that Cummings was experimenting with multiple ways of modifying his poetic expression.

While fewer in number, the linguistically traditional elements are

nonetheless important. As many sonnets have regular as irregular grammar (50 percent each); usually the abnormality takes the form of word

mixing in preference to word dismemberment, although both of these

modes still are regular in 53 and 84 percent of the sonnets. So, too,

is the overall typographie nature of the majority of the sonnets

(52 percent) normal. However, occasional irregularities in visual

appearance do occur; among these are found instances of typographie

spacing, irregular linear level, pictography, and typographie irony

(use of ampersands, numerals, etc.).

Table Il continues to sketch the general nature of the content

variables within Cummings' sonnets by giving percentage appearance

of specifie values. Sixty-eight percent of ali Cummings' sonnets use

natural imagery; this number is lower than one might expect to find

in a traditional poet. ln contrast, a high percentage (88) of the

-37-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

sonnets are people-oriented; 58 percent of these include the persona,

demonstrating that Cummings remained a traditionalist in terms of his

focus and point of view.

Furthermore, a majority of ali sonnets

concern women.

Congruent with his experimental approach, intermingling the traditional with the innovative, Cummings wrote more of his sonnets in

neutra! or mixed, rather than emotional or romantic, language.

Likewise, an analytic tone predominates, with emotional and humorous/satiric following.

Finally, more than half of his sonnets are

neither "romantic" in terms of basic style and intent nor "loving"

in theme.

Philosophie and impressionist styles account for more

sonnets than romantic, just as themes of life combined with those

of society and man surpass those of love.

Experimentalism

The first indicator that E.E. Cummings is a dedicated experimentalist

with the sonnet is his creation of 155 different rhymes schemes for

his 212 sonnets.

Of these, 9.4 percent determine the form as being

ltalian, 27.4 percent as English, 17 percent as Combined, and 46.2

percent--the largest single value--as lrregular.

Contrarily, Cummings

was fairly conventional in his use of rhyme.

Twice he wrote

unrhymed sonnets, occasionally he combined rhyme and not-rhyme,

but he rhymed the majority of his sonnets (82 percent) in sorne

fashion or another.

What superficially appears as free or blank

-38-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

verse upon first sight almost always becomes rhyme approximate in

accent or sound (half-rhyme) at second glanee.

Cummings also inno-

vated with sound similarities, attempting to have recognized as rhyme

family vowel sounds, such as "grow/you, do/now, be/may, knows/kiss,

to/no, why/the" (see sonnets 144, 145, 153, 156, 157, 162).

The poetic turns that we find within these sonnets are nearly as

myriad as the rhyme schemes and types. The 79 percent irregularity

of this variable diffuse into seventy-eight different placements, occurring singly or in combination both between and within !ines. The

single most repetitive irregularity cornes between !ines thirteen and

fourteen (8 percent).

The second indicator is his experimentation with the traditional

iambic pentameter meter (64 percent). Yet, while Cummings became

expert at attaining the probable outer limit of formai structure,

rhyme, and break combinations, he remained stable in his choice of

experimental metric variations from the iambic foot ( IAMBVAR) and

pentameter meter (METVAR).

The most frequently occurring

IAMBVAR values are initial hard syllable or word, trochaic/iambic

tensions and reversai, short lines of three-to-four feet, several anapests

and dactyls (49.5 percent); these values plus long !ines of six-to-eight

feet (23 percent); ali previous values except long and short lines

(15.5 percent). ln a similar fashion, the pentameter variable

(METVAR) falls into three major value groups. Discarding the

35.8 percent sonnets to which this variable is not applicable, 41

-39·

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

percent of the remaining 136 sonnets have few or no iambic pentameter !ines or other patterned metric, 38.8 percent have five-foot

!ines but with a combined pattern of iambic and other, and 20

percent have a dominate iambic pattern but with an irregular number

of feet per line. The finaly one percent includes two majority

trochaic foot sonnets with !ines of varying length.

A third characteristic of Cummings' experimentalism resides in his

eccentricities with the typographie nature of sorne of his sonnets.

Only 52.4 percent of Cummings' sonnets are written conventionally.

ln the remaining sonnets he introduced such typographie innovations

as words, syllabes, or letters spaced across the page (12.3 percent);

irregular linear levels of one-to-three !ines (38.7 percent), four-toseven !ines (6.6 percent), or over eight !ines (2.4 percent); pictography, where the visual poem echoes its meaning (2.4 percent); or use

of ampersands, equal signs, and numerals (4. 7 percent).

How Cummings chose to divide his sonnets into stanza units and to

determine their phraseology constitute not only two more methods

of carying a sonnet's format, but also indicate his dissatisfaction

with traditional stanzas and forms of punctuation. ln addition to

being a formai factor, SPACE is sometimes, but not necessarily,

related to the TYPO variable in that Cummings often used typographically irregular !ines as a means of composing structural units.

At other times he merely increased the number of blank !ines

-40-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

between blacks of type, thereby simulating stanzas.

lt is interesting

to note that 18.4 percent of the sonnets are displayed on the page

in a solid black form, in octave/sestet divisions, or in three quatrains

with a final couplet; 10.8 percent have one-to-three irregular stanzas;

44.3 percent have four-ta-six irregular stanzas; and 26.4 percent have

over seven unequal stanza units. By the same token, LINFRAS

measures the use of lines as a form of punctuation or linear phrasing.

lt, tao, is often related to the TYPO variable; Cummings frequently

(25.4 percent) varied line level instead of using the proper form of

punctuation. At other times or in combination with linear level

variation, he used the line end as a phrasing unit (58 percent).

Another of Cummings'areas of innovation is his manipulation of the

elements of language or communication. As 1 earlier explained,

Cummings' linguistic experimentation with grammar (50 percent),

semantics (81 percent), and punctuation (84 percent) is integral to

his philosophy of poetics : improvise to attain immediacy of the

experience.

ln addition, Cummings so indulged in the economie,

compacted individualistic style exemplified by Dante Gabriel

Rossetti and which includes the use of unusual, archaic, and Latinate

words that he created a special form of imagery--verbal imagery-wherein he varied ward form and function in arder to attain an

impressionistiè, sometimes esoteric, effect.

Other linguistic abnormalities which Cummings adapted into his

sonnets also did not originate with him.

ln fact, (1) compression

-41-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

or ellipsis, (2) creation of new words by adding the "un-" prefix

and using it to express the negative of the root word, and (3) corn•

pounding old words in a new way, even assigning a new sense and

function in sorne cases, 4 are evident in English sonnets since the

time of Shakespeare. As the variables NEWWORDS and NEWMEAN

explicate, these three forms among others appear in Cummings' sonnets.

The four most repetitive NEWWORDS values by order of recurrence

are compounds, -ly, un-, and other word substitution for nouns.

Correspondingly, the methods by which Cummings varied the meanings

of these newly created words (NEWMEAN) divide overwhelmingly

into three groups : extension of the word's meaning by using it in

a different form and context (a symptom of syntactic dislocation);

extension of basic meaning by compound, hyphen, prefix, or suffix;

and ambiguity of meaning through use of unreferenced pronouns or

substantives instead of nouns.

Lastly, as table Il illustrates, Cummings had certain favorite topics

upon which he centered his sonnets, but he embraced no thematic

unity per se.

Love may have accounted for the foremost single

stylistic approach (34 percent) and theme (42 percent) in his sonnets,

but neither of these constitutes a majority.

ln fact, philosophie and

impressionistic sytles total 46 percent while life, society, and man

account for 42 percent of ali sonnet themes.

Furtharmore, of the

52 percent of the sonnets in which women appear, the poet's

reaction to them can be divided into five attitudes : ( 1) negative,

5 percent; (2) positive/impersonal, 7 percent; (3) positive/sympathy,

-42·

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

7 percent; (4) love/physical, 10 percent; and love/spiritual, 23 percent.

Cummings described woman as playmate, soulmate, and inspiration;

she is obtainable and she is real.

As poet/persona he is either an

impartial observer, describing intercourse and its feelings, or an emotional participant, regarding the beloved in a spiritual as weil as

physical fashion.

Rarely does the woman have a name; rather, she

is the archetype of Woman and, as such, exists only in his perception

of her effect upon him.

Nevertheless, in his experimentaion with the customary attitudes,

style, and themes, Cummings did retain one key traditional concept

the idea that love may encourage or allow the poet to participate in

an elevated state or feeling. His repeated emphasis on the ennobling

qualities of love--Cummings believed that through love man broke

from the bonds of egotistical self, related to the other, and achieved

a holistic vision of the universe 5 --has occasioned Cummings being

called both a romantic and a transcendentalist 6.

Conclusions

Undoubtedly the results of the content analysis indicate that E. E.

Cummings' concepts about the nature of the traditional and an

experimental sonnet were interwoven.

Synthesizing historical tech-

niques with his present fortes and interests, Cummings' attitude

towards sonnet deviees, content, and language was as empirical as

that towards a focus on woman-worship and tightly-knit form.

-43-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

The challenge before Cummings was to infuse new into the old

without crumbling historical customs.

He wanted to discover his

own poetic strengths and weaknesses at the same time as he searched

for those elements which made an effective modern sonnet.

he worked bath within and against the sonnet tradition.

Thus,

ln this

process Cummings broadened the concept of what elements a poet

can successfully manipulate during his effort to communicate a poetic

vision or experience. To the previous variables of form, content, and

semantics, Cummings added syntax, punctuation, grammar, and typography or visual appearance.

Simulteneously embracing and flouting

conventional poetic norms, E. E. Cummings gradually discarded the

definitional features of the sonnet until only one criterion remained-the sonnet is (usually) a fourteen-line, iambic pentameter, lyric poem.

2506 56th Street

Lu bbock, Texas 79413

Judith A. VANDERBOK

U.S.A.

-44-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

NOTES

1- See Theodore Spencer, "Technique as Joy," Perspectives USA, 2

(Winter 1953), 23-29; Norman Friedman, e.e. cummings : The

Growth of a Writer (Carbondale : Southern Illinois, University

Press, 1964) and e.e. cummings : The Art of His Poetry

(Baltimore : The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1960); and

Bethany Dumas, E.E. Cummings : A Remembrance of Miracles

(London : Vision Press, 1974).

2- Norman H. Nie et. al., Statistical Package for the Social Sciences,

2nd. ed. (New York : MxGraw-Hill, 1975).

3- E.E. Cummings, Poems 1923-1954(Harcourt, Brace & World, 1954),

p. 397.

4- Dorothy L. Sipe, "Shakespeare' s Metrics," Yale Studies in English,

166 (1969), 189-92.

5- Patricia Tai-Mason, "The Whole E.E. Cummings," TCL, 14 (july

1968), 90-97.

6- Friedman, Growth, p. 5.

-45-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

TABLE 1 (continued)

TRADIT/ONAL AND EXPERIMENTAL ELEMENTS

OF E.E. CUMMINGS' POETRY (BY PERCENTAGE

OF HIGHER APPEARANCE)

Trad.

Percent

Variables

Exper.

Percent

Linguistics

IRSTART (no initial cap.)

RHETPUNC (rhetorical punc.) ·

CAPCOM (cap. of common

nouns)

NOCAPPRO (noncap. of proper nouns)

RHETCAP (rhetorical cap.)

IRPERIOD (irreg. period)

1RCOMMA (irreg. semicolon)

1RSEM (irreg. semicolon)

1RCO LON (irreg. colon)

1ROU PT (irreg. question mark)

1R EXC LAM (irreg. eclamation

point)

1RPAREN (irreg. parenthesis)

PARENS (use of parentheses)

1RDASH (irreg. dash)

IRHYPHEN (irreg. hyphen)

ELLIPSIS (use of ellipsis)

1ROUOTE (irreg. quotation

marks)

96.7

58.0

61.8

80.7

64.6

84.4

60.8

69.3

60.4

96.2

98.1

79.2

81.1

73.1

85.8

78.8

97.6

-48-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

TABLE 1 (Continued)

TRADITIONAL AND EXPERIMENTAL ELEMENTS

OF E.E. CUMMINGS' POETRY (BY PERCENTAGE

OF HIGHER APPEARANCE)

Trad.

Percent

Variables

Exper.

Percent

Linguistics

TYPO (linear level)

TYSPACED (letters spaced)

TYIRLINE (irreg. level)

TYSEEBE (typo pictures)

TYIRONY (typo. irony)

SYNTAX

RUNONL (run-on lines)

RUNONI (run-on interrupters)

SENTF RAG (sentence fragments)

H EAVY (juxtaposed accented

words)

1RSENSTR (irreg. sentence

structure)

SYNDISN (syntactic dislocation to form a noun)

SYNDISAJ (ta form adjective)

SYNDISAV (to form adverb)

SYNDISVB (to form verb)

52.4

87.7

52.4

96.6

95.3

91.5

75.0

72.6

77.4

54.2

90.6

51.4

60.8

96.2

80.7

·49-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

TABLE Il

CONTENT VARIABLES IN E.E. CUMMINGS' SONNETS

(BY PERCENTAGE APPEARANCE) .·

Variables

Percent

NATURE (comparisons with)

PEOPLE (concern for)

Persona-centered

WOMEN (attitude towards)

LANG (language)

Neutra!

Laudatory

Satiric

Mixed

TONE

Analytic

Emotional

Hu morous/satiric

GENRE (basic Styles)

Love

Philosophy

Impression

Satire

Portrait

Personification

Praise /celebration

67.5

88.2

57.5

51.9

53.8

2.8

1.9

41.5

47.6

31.3

21.2

34.0

25.0

21.2

10.4

5.2

2.4

1.8

-50-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.

TABLE Il (Continued)

CONTENT VARIABLES IN E.E. CUMMINGS' SONNETS

(BY PERCENTAGE APPEARANCE)

Variables

THE ME

Love

Li fe

Society/man

Nature

Science/art

Time/death

Percent

41.5

29.7

12.3

9.9

3.3

3.3

-51-

Extrait de la Revue (R.E.L.O.)

XIII, 1 à 4, 1977. C.I.P.L. - Université de Liège - Tous droits réservés.