View the environmental scan

Recreation Section Plan

Environmental Scan

EXAMINING DEMOGRAPHIC, RECREATION SECTOR, VOLUNTARY SECTOR AND FUNDING TRENDS

NOVEMBER 2010

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1

2. Demographic Trends .................................................................................................................... 1

Aboriginal People .............................................................................................................................. 2

Population Growth & Immigration ............................................................................................ 5

Economic Growth .............................................................................................................................. 7

3. Recreation Sector Trends ........................................................................................................... 9

Health Trends ................................................................................................................................... 10

Participation...................................................................................................................................... 11

Barriers ............................................................................................................................................... 12

4. Key Trends in the Voluntary Sector ................................................................................... 13

Increasing Accountability............................................................................................................ 15

Diversity of Population................................................................................................................. 15

Increasing Partnerships and Collaboration......................................................................... 15

Technology and Knowledge Transfer..................................................................................... 16

5. Key Trends in Funding .............................................................................................................. 16

Financial Capacity and Sustainability .................................................................................... 16

Increasing Entrepreneurialism................................................................................................. 16

Funding and Accountability ....................................................................................................... 17

Moving to Outcome Measurement .......................................................................................... 17

Flexibility in Funding and Accountability Arrangements ............................................. 18

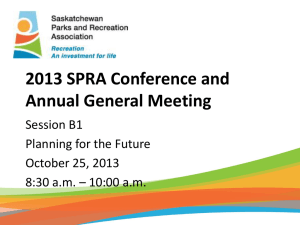

6. External Context ........................................................................................................................... 18

Priorities for the Saskatchewan Parks and Recreation Association ......................... 18

SPRA’s vision is: ............................................................................................................................... 18

SPRA’s mission is: ........................................................................................................................... 18

Priorities of the Government of Saskatchewan.................................................................. 20

New Priorities .................................................................................................................................. 21

7. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................ 21

8. Bibliography .................................................................................................................................... 23

1. Introduction

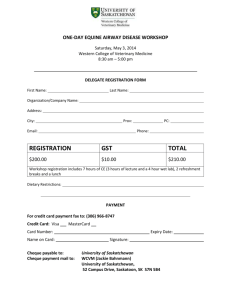

The Saskatchewan Parks and Recreation Association (SPRA) has undertaken a process to develop a Recreation Section Plan. The Plan will enable the SPRA to align its funding with strategic priorities and provide a framework to assess the extent to which funded programs have achieved desired outcomes. The process of developing the plan has been designed to ensure the participation and feedback of the 32 Provincial Recreation Associations (PRAs) funded through SPRA from the Saskatchewan Lottery Agreement.

Four broad categories of literature and research were reviewed for this project. The first relates to demographic and economic trends for Saskatchewan. The second relates to trends effecting parks and recreation. The third pertains to trends in volunteerism. The final body of literature reviewed pertains to funding and accountability practices specific to not-for-profit entities in Canada.

The final section of the paper deals with communication considerations.

2. Demographic Trends

The SPRA has a long tradition of promoting healthy and active communities in

Saskatchewan through the emphasis of a strong network of parks and recreation. As

Saskatchewan and its population change, so too will people’s preferences and expectations related to parks and recreation and with it the priorities of the SPRA.

Figure 1 (Government of Saskatchewan 2006)

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 1

Like other provinces in Canada, Saskatchewan’s population is ageing (Figure 1). According to the 2006 census, “Saskatchewan continues to rank first with respect to the percentage of population aged 65 and over. However, the rate of increase in this population between 2001 and 2006 was much higher in every other province and territory than it was for

Saskatchewan, except for Manitoba” (Government of Saskatchewan, 2006). In other words,

Saskatchewan’s population is already older than that of other provinces, although other provinces are catching up.

In addition to a large number of “baby-boomers” who are getting ever closer to retirement age, Saskatchewan also has a large number of younger people know as the “echo” or “y” generation. The age distribution of the Saskatchewan population is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 (Elliot, Construction Labour Market Database 2010a)

Aboriginal People

Compared to most other provinces, Saskatchewan is home to a proportionally large aboriginal population (Figure 3). At just under 15%, aboriginal people compose a significant component of Saskatchewan’s population (Elliot, Sask Trends PARWC June 2, 2009).

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 2

Figure 3 (Elliot, Sask Trends PARWC June 2 2009)

And unlike their non-aboriginal counterparts, the aboriginal population in Saskatchewan population is younger:

• In 2006, 55% of the aboriginal population was under 25 years of age compared with

31% of the non-aboriginal population.

• 18% of the aboriginal population was 45 years of age or older compared with 44% of the non-aboriginal population (Figure 4) (Elliot, Sask Trends PARWC June 2, 2009).

Figure 4 (Elliot, Sask Trends PARWC June 2 2009)

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 3

The Saskatchewan aboriginal population has been growing whereas the non-aboriginal population has been shrinking. The aboriginal population grew by an average of 2.5% over the last ten years. Over the same period, the size of the non-Aboriginal population has declined (Figure 5) (Elliot, Sask Trends PARWC June 2, 2009).

Figure 5 (Elliot, Sask Trends PARWC June 2 2009)

In addition to having different characteristics with regard to population growth rates and age, aboriginal people in Saskatchewan also tend to be located in different areas of the province, as shown in Figure 6. As a proportion of the total population, aboriginal people are more likely to live in Prince Albert and North Battleford. They are less likely to live in

Regina and Saskatoon and are almost non-existent in sourthern urban centres such as

Estevan and Swift Current (Elliot, Sask Trends PARWC June 2, 2009).

Figure 6 (Elliot, Sask Trends PARWC June 2 2009)

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 4

Population Growth & Immigration

Until recently, Saskatchewan’s population was shrinking due to out migration and modest in-migration and immigration. In the 20 years preceding 2005/06, Saskatchewan experienced a net out-migration in every individual year as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7 (Elliot, Construction Labour Market Database 2010a)

That pattern changed in Saskatchewan due to robust economic and job growth. For the last five years, Saskatchewan has been growing through in-migration and immigration. On

July 1, 2010, Saskatchewan’s population reached an all-time high at 1,045,600 (Statistics

Canada, 2010). Projections from Statistics Canada and the Sask Trends monitor estimate that Saskatchewan’s population could grow to between 1.1 – 1.3 million people in the next

20 years (Elliot, 2010).

The provincial government has placed considerable emphasis on population growth through interprovincial migration and immigration. The Saskatchewan Immigrant Nominee

Program saw 2,914 nominees invited to the province last year. This resulted in more than

9,000 newcomers when accounting for family members. Targets for future years are expected to continue to increase (Government of Saskatchewan, 2010a). Figure 8 shows the sharp increase in international immigration in Saskatchewan that has occurred over the last

5 years.

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 5

Figure 8 (Elliot, Construction Labour Market Database 2010a)

There is some indication that the population growth occurring in Saskatchewan is not confined to Regina and Saskatoon. While population growth is strongest in the two cities, growth is occurring in other areas as well. Over the period from 2006 to 2009, the population in the Regina and Saskatoon metropolitan areas grew by 22,000 compared with 16,000 in other parts of the province

(Elliot, 2010b).

Notwithstanding recent population growth, long term patterns clearly show that cities in Saskatchewan are growing at the expense of towns, villages and rural areas (Figure 9). The

Figure 9 (Elliot 2010b) notable exception are First Nations Reserves, which are the fastest growing community type of the last 20 years (Elliot, 2010b).

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 6

Economic Growth

Saskatchewan has seen country-leading economic growth in the last number of years and that growth is expected to continue into the foreseeable future. The Royal Bank of Canada has recently forecast Saskatchewan to lead the country with GDP growth of 6.3% in 2010

(Chabun, 2010). Where jobs were once scarce in Saskatchewan, they are now more plentiful.

An entire generation of people grew up in an era of more people than jobs in Saskatchewan, leading to out-migration and little immigration. For the last 5 years, Saskatchewan has been in a situation of having more jobs than people. The twin factors of economic growth and demographic changes indicate that having abundant jobs is a situation that is likely to persist for some time. Economic and population growth has been reflected in increased expenditures by government (Figure 10), increased capital investment in both public and private sectors, increases in corporate profits (Figure 11) and increased weekly earnings

(Figure 12).

The combination of more young people moving to or back to Saskatchewan, an ageing population with an increasing cohort of seniors, a significant increase in the number of new

Canadians, a growing aboriginal population that increasingly lives off-reserve, and greater economic prosperity show clearly that Saskatchewan is changing. The recreational needs and interests of Saskatchewan people will change along with the province’s demographic profile.

Figure 10 (Elliot, Construction Labour Market Database 2010a)

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 7

Figure 11 (Elliot, Construction Labour Market Database 2010a)

Figure 12 (Elliot, Construction Labour Market Database 2010a)

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 8

3. Recreation Sector Trends

In addition to demographic and economic changes occurring in Saskatchewan, there are sweeping changes occurring across Canadian society that have implications for the recreation sector. Former Saskatchewan Premier Roy Romanow provides a good summary of the changes facing Canadians in the introduction to Caught in the Time Crunch: Time Use,

Leisure and Culture in Canada . The report finds that Canadians are:

…caught in a time crunch, struggling to meet the competing demands of: a workplace that can reach out to them 24/7; children and parents who need a supportive environment; and their own needs to refresh body and mind through family time, leisure and culture activities. More and more Canadians are working in jobs requiring non-standard hours – weekends, evenings, nights, and rotating shifts. More Canadians are providing care to dependent seniors. Women, especially, are feeling the pressure.

They take on the lion’s share of raising children and providing care to seniors.

Adolescents are increasingly exceeding recommended times for TV and video games.

Meanwhile, the portion of parents reading to pre-school children and kids participating in organized activities appear to be in a holding pattern. On the other end of the age scale, the proportion of retired seniors engaged in active leisure activities has remained steady and more seniors are volunteering in their community....

Canadians are finding less and less time to be physically and socially engaged in activities.

We are more likely to rely on TV for entertainment than go out to a play or movie, play some pick-up hockey or take a walk in the park. Fewer of us are finding the time to visit

National Parks and National Historic Sites (Canadian Index of Wellbeing, 2010) .

At the Alberta Recreation and Parks Association 2009 annual conference a presentation by

Rethink (West) outlined a number of general trends in Canadian society. The column on the left represents the past/present while the column on the right represents the present/future.

Shifting From

Formal, highly structured activities

Team sports and activities

Directed programs – teaching

Fitness focus

Active orientation

Consumptive activities

Indoor “facility” focus

“doing something”

Activity as “end”

Shifting To

Informal, self-scheduled, casual

Individual activities

Self-directed learning

Holistic wellness

Relatively passive

Environmentally friendly

Home and outdoor focus

“experiencing” – quality/depth

Activity as “means” (to bigger ends)

(RETHINK (West) Inc., 2009: 27)

While people in our societies are finding their days busier, there is also evidence that priorities are shifting from work toward leisure time. According to the Canadian Index of

Wellbeing, "the proportion of Canadians working more than 50 hours a week declined from a high of 14.9% in 1996 to 11.0% in 2009" (2010). This finding is supported by a study

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 9

done for the Alberta Recreation and Parks Association by Harper (2008) that indicates that "the number of Albertans who put leisure before work has risen 20% since 1996."

From 1996 to 2007 the number of respondents who indicated that work was their top priority dropped from 48% to 32% while the number that indicated leisure was thier top priority rose from 27% to 47%. These findings are reinforcing what employers have been reporting anecdotally for a number of years - that employees, especially young new entrants to the workforce, place a greater emphasis on balancing work and family life and are less likely willing to work long hours, overtime or weekends.

These broad changes in our society will increasingly have implications for how not-forprofit organizations deliver programs to their clients, who their clients are, and what services and programs their clients want.

Health Trends

People are increasingly aware of the health benefits of physical activity. Schools, health regions and the media regularly highlight the benefits of physical activity (District of West

Kelowna, 2009). According to the Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card on Physical

Activity for Children and Youth “…increased physical fitness and active living opportunities have positive effects on academic performance... including a 24% increase in math scores over a two-year period. Notwithstanding the benefits to children of an active lifestyle, 87% of children and youth are still not meeting the recommended 90 minutes of physical activity a day (Active Health Kids Canada, 2009). While the benefits of an active lifestyle for children are well documented, as a society we remain challenged to ensure that our children realize those benefits.

In a recent presentation to Parks and Recreation

Ontario on the health benefits of recreation,

Rosella (2010) points out that North

America has a growing problem with obesity.

In Saskatchewan, less than 10% of the population was considered to be obese in 1985. Figure 13 shows that by

2004/05 that number had grown to between

20 and 25% of the population.

Figure 13 (Rosella 2010)

According to a new report on obesity by the Organization for Economic and Cooperative

Development (OECD) “…Canadians are struggling to win the battle against obesity” (Keller,

2010). The OECD reports that one in 4 Canadians are obese and that number is expected to increase by 5% in the next 10 years (Keller, 2010).

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 10

The trend toward increasing problems with weight goes along with an increase in the amount of time that children and adults are spending in front of their TVs and computers.

According to the Canadian Index of Wellbeing:

“The proportion of adolescents who exceeded the maximum recommended 2 hours a day on TV and video games rose from 27.2% in 2003 to 31.7% in 2007/2008. When all screen time (TV, computer use, video games), was included, those who exceeded

2 hours a day jumped from 54.5% to 63.7%, with about 70% of boys and 57% of girls exceeding the 2-hour threshold” (Canadian Index of Wellbeing, 2010: 10) .

Participation

As their days fill with competing demands Canadians are spending less time on social leisure activities dropping from 15% of their day in 1998 to 12% in 2005 (RETHINK

(West) Inc., 2009). Canadians are increasingly pressed for time due to non-standard working hours, the provision of care (especially by women) to seniors, exceeding recommended levels of screen time and increased commute times (Canadian Index of

Wellbeing, 2010: 4-13).

Recent research in Saskatchewan into free-time activities supports national findings. The most commonly reported daily activity in which Saskatchewan people participate was “two hours or more of ‘screen time’ outside of work or school” (Insightrix Research, 2010: 2).

Other prevelant activities included gardening and yardwork, walking, running or jogging, visiting local parks, attending cultural events, other physical activities and visits to

Saskatchewan parks.

According to the Insightrix research, of those participating in the study:

Over one-third participated in unorganized sports (34.8%)and attended sporting events (35.5%) at least once per month during the past year. A smaller proportion

(22.2%) participated in organized sports at least once per month.

Almost one-half (43.9%) participated in nature-based recreation activities in the water (e.g., fishing, swimming, boating, water skiing, etc.) at least once per month in the past year. Smaller proportions of respondents reported participation in naturebased recreation in the winter (e.g., XC skiing, snowmobiling, snowboarding/downhill skiing) (28.0%) and other nature-based recreation (e.g., hiking, camping, hunting,

ATVing, horseback riding, etc.) (38.7%) during the same time period.

Over three-quarters (78.5% ) visited Saskatchewan provincial parks at least once during the past year and just over one-quarter (25.8%) visited Saskatchewan provincial parks at least once per month.

On a national level, total annual household expenditures on culture and recreation, even when adjusted for inflation, rose by 20% from $10,000 in 1997 to $12,000 in 2006

(Canadian Index of Wellbeing, 2010: 23).

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 11

Barriers

There exist a range of barriers which prevent people from participating in the sort of activities offered by Provincial Recreation Associations. As Saskatchewan grows increasingly diverse, parks and recreations associations will be increasingly challenged to ensure that participants in their programs and services are representative of the wider

Saskatchewan population.

According to the Canadian Index of Wellbeing (2010: 8), low household income, recent immigration and aboriginal status are “…significant determinants of participation in organized sport or structured lessons” and that non-participation is most likely caused by

“….lack of financial ability to pay for such activities.”

Similarly, Insightrix (2010: 9) found that participation fees being too expensive was a barrier to participation in leisure/free time activities for over 1/3 of respondents in their research.

Lack of time owing to either work/school or household activities was an even larger barrier with about half of respondents identifying this as a barrier to participation. Figure 14 shows a detailed breakdown of barriers to participation in leisure/free time activities.

Figure 14 (Insightrix Research 2010)

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 12

4. Key Trends in the Voluntary Sector

According to Human Resources and Skills Development Canada “In 2004, 12 million

Canadians volunteered, and contributed almost 2 billion hours - the equivalent of 1 million full time employees” with an estimated replacement value of “…greater than $14 billion annually” (HRSDC, 2009:3). Many if not most not-for-profit organizations are highly dependent on volunteers to accomplish their missions.

A review of the literature and the interviews with key informants highlights the many issues with which the voluntary sector is currently grappling. This list is not exhaustive but is intended to underline the main concerns of the sector. Not every issue will be faced by every Provincial Recreation Association every day, but it is helpful to think about the broad range of issues that could be facing the PRAs today and in the future.

The 2007 Canada Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating is a rich source of information on the changing trends of volunteerism at the national and provincial level

(Hall, 2009).

Canadian and Saskatchewan Rates of Volunteering - The rate of volunteering in Canada has stayed relatively stable between 2004 and

2007 at 45 per cent (Hall, 2009). The actual number of Canadian volunteers increased over this same time by 5.7 per cent largely as a result of the population increase. During the same time period, the rate of volunteering in Saskatchewan grew from 54 per cent to 59 per cent (See

Figure 15) (Hall, 2009). About

465,000 Saskatchewan residents participated in volunteer activities.

This finding is consistent with recent research done in Saskatchewan by

Insightrix, which found that “…over one half of respondents volunteered with local community groups in a leadership role (59.8%) (Insightrix

Research, 2010: 8). A somewhat lower percentage of respondents indicated that they did volunteer work on a regular basis at 44.8%

(Insightrix Research, 2010: 39).

Figure 15 (M. D. Hall 2009)

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 13

Broad-based but Thin Support - Nationally, the top 25 per cent of volunteers were responsible for over three quarters of the total volunteer hours. Support for charitable and not-for-profit organizations comes from a broad but thin base of people across the country.

The top 25 per cent of donors who also volunteer are only 14 % of the national population, but they contribute 59% of total donations and 40 per cent of total volunteer hours.

Average Hours Volunteered Decreased - The average number of hours that Saskatchewan people volunteered decreased from 188 hours in 2004 to 147 hours in 2007 (Hall, 2009).

Together with Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan had the lowest hours of volunteerism in the country and in fact, the hours volunteered in Saskatchewan dropped 21% between 2004 and 2007, the largest drop in the country (Hall, 2009).

The Internet - Use of the Internet, as a tool in volunteering, is appearing to be increasing slowly with just under one quarter of volunteers using it in some way as part of their volunteering efforts (Hall, 2009).

Sports and Recreation Attract Volunteers - More than one in ten Canadians who volunteered, volunteered for sports and recreation organizations (11 per cent). Average volunteers hours contributed to sports and recreation organizations was 119, exceeded only by the number of hours worked for religious organizations (Hall, 2009).

Age and Volunteerism - The likelihood of volunteering decreased with age while the number of hours worked increased. In Saskatchewan, sixty-eight per cent of 15 to 24 year olds volunteered while 46 per cent over 65 volunteered. Those over 64 volunteered for an average of 177 hours while the 15 to 24 group worked for an average of 116 hours. Not surprisingly, the 25 to 34 year old age group generally volunteered less and worked fewer hours (Hall, 2009).

On a national level, volunteering for culture and recreation organizations has dropped, especially among those 25 to 34 years of age” (Canadian Index of Wellbeing, 2010: 16).

Furthermore, according to Rethink (West), important changes are taking place in voluntarism:

• Decreasing commitment – declining interest in long term roles in favour of short term projects/assignments

• Diminished interest in taking on leadership roles – at both operational and governance levels

• Most sought after volunteer experiences will be shorter term, personally meaningful and developmental. (RETHINK (West) Inc., 2009: 71)

However, as Saskatchewan’s population ages, there will be an opportunity to take advantage of an increasingly large pool of retirement age people who may be willing to give of their time and skills as volunteers in the recreation sector. According to the Canadian Index of

Wellbeing “the percentage of retired seniors participating in formal volunteering activities jumped from 20.5% in 1992 to 30.5% in 2005” (Canadian Index of Wellbeing, 2010: 13).

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 14

Youth and Volunteerism - The likelihood of volunteering later in life is influenced by earlier experience with volunteering. Experiences for youth like participation in student government, having parents who volunteered, being active in a religious organization, belonging to a youth group and having participated in an organized team sport are influential in encouraging youth to volunteer as adults (Hall, 2009).

Immigrants and Volunteerism - Immigrants were less likely to volunteer than native born

Canadians (40 per cent to 49 per cent) but devoted more hours to volunteering (171 to

163). These differences are likely related to their economic and personal circumstances

(Hall, 2009). Immigrants also reported many more barriers to volunteering than native

Canadians including:

• not sure about how to become involved (33% to 22%);

• costs of volunteering (23 % to 15%); and

• dissatisfaction with a previous volunteering experience (11% to 7%) (Hall, 2009).

Increasing Accountability

Donors, particularly larger donors, are demanding accountability for their contributions and are often seeking a say in how their contributions will be used. Donors are concerned that money will not be used effectively and will often want to align their donations with their business interests (Canadian Centre for Philanthropy).

At the same time, governments are demanding greater accountability from agencies they fund. These agencies, may in turn, pass on accountability requirements to their funded organizations. Funding scandals at the federal level, like the “sponsorship scandal” and independent watchdogs, like auditors, are resulting in governments at all levels, federal, provincial and municipal, to rethink contracting processes.

Diversity of Population

Saskatchewan is becoming increasingly diverse with a burgeoning First Nations population and with New Canadians. These two groups are not being represented in the leadership, governance and orientation of the voluntary sector (Canadian Centre for Philanthropy).

Cultural sensitivity and recognizing that English may not be the first language of new participants may not have been a priority for PRAs in the past, but it will become increasingly important.

Learning how to work and engage with First Nations people was identified during the interviews of key informants as a huge challenge. Informing PRAs of best practices and helping them develop the skills and abilities to build and sustain relationships with First

Nations communities is and will be an ongoing challenge for SPRA.

Increasing Partnerships and Collaboration

Funders are often demanding that organizations actively engage in and develop partnerships with other like agencies in their communities. Often, these kinds of relationships are a requirement in funding agreements. Partnerships and collaborations require new skills from organizations, skills like negotiation, compromise, sharing authority, and joint investment of resources (Canadian Centre for Philanthropy). Collaboration,

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 15

particularly with non-traditional partners, yields access not only to new resources but to different ways of thinking about the work and emerging opportunities (Struthers, 2010).

Technology and Knowledge Transfer

Voluntary sector organizations are seen to be falling behind in the use of technology when compared to the private and public sector (Canadian Centre for Philanthropy). The use of technology to create environments where “virtual volunteers” can make a contribution to their community is not widely used. The internet affords opportunities to connect organizations to undertake a wide range of activities like the active knowledge transfer between organizations. Individual volunteers connected online could provide consulting services, assisting with human resources problems, could help design newsletters and logos, could assist with research, design and deliver e-surveys of memberships or lead advocacy efforts. Where volunteers are often struggling for time to contribute, the internet provides greater flexibility and new opportunities to contribute (Cravens, 2000).

Technology provides unique opportunities for the “active” transfer of knowledge between organizations, agencies and individuals, by moving beyond the usual online library of resources to opportunities that encourage discussion and dissemination of practical ideas and activities. Multiple channels or methods of communicating information or knowledge is more effective (Zarenpoush, 2007). A two way flow of information is optimum and can often be done through establishing communities of practice involving individuals and organizations with similar issues and interests (Zarenpoush, 2007).

5. Key Trends in Funding

Financial Capacity and Sustainability

According to a recent article by Marilyn Struthers, who has long time involvement in the not-for-profit sector, organizations that are doing well financially share six capacities. These capacities included financial literacy, sustainability modeling, nurturing participation, meaningful planning, communication, and the capacity to build relationships (Struthers, 2010).

Core funding of organizations is seen by the not-for-profit sector as a critical component to the sustainability of their organizations. Chasing project-based funding is seen as potentially contributing to “mission drift”, a significant issue for the average not-for-profit organization that is driven by its mission (Canadian Council on Social Development, 2003).

At the same time, funders are often questioning core funding and whether it curtails innovation and creativity by the not-for-profit sector.

Increasing Entrepreneurialism

As governments and funders are moving from core funding of organizations to more project based funding arrangements or directed funding contributions, the not-for-profit sector is changing as well. The focus now is on social enterprise, enterprising nonprofits, and mission-driven for-profits (Struthers, 2010). The non profit sector appears to be moving away from discussion of reliance on, or even hope for, improved or increased government funding. Many have simply withdrawn from the discussion, moving instead to learning about new highly collaborative models of operation and more entrepreneurial ways of thinking about and generating revenue (Struthers, 2010).

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 16

Funding and Accountability

What does accountability mean? Accountability has various definitions and there should be a clear understanding of to whom and for what an organization is accountable.

Organizations often have multiple levels of accountability which can have the effect of skewing an organization’s attention. Recognition should be given to both upward accountability (i.e. to the funding source) and also downward accountability (i.e. to the client or member) (Ebrahim A. , 2010).

The four whats of accountability include responsibility for finances of the organization, governance by the not-for-profit board, performance and responsibility for defining the mission of the organization. These areas of responsibility are not mutually exclusive but need to thought about as an integrated whole (Ebrahim A. , 2010).

Funding and accountability are being increasingly linked by funders. It is the direct result of the increased demand for accountability described earlier. As a result there has been a move to more outcome-based arrangements in funding agreements and a shift from input and output measurement. This development relates to the rise of “new public management” or “results based” management in the mid to late 1990’s (Hall M. H., 2003).

Moving to Outcome Measurement

Moving to outcomes measures does pose some difficulty for the not for profit sector. Some of these challenges are:

• The collection and assessing of information;

• Learning to evaluate programs and organanization effectiveness;

• Involvement of stakeholders in the evaluation process;

• Difficulties in measurement including trying to assess long-term changes in short timelines;

• The investment in time, funding and staff expertise to undertake evaluation activities;

• Most evaluation techniques are designed for the private sector or for governments and do not take into account the complexities of “mission” driven organizations;

• Low tolerance for mistakes and poor performance (Hall M. H., 2003).

Funders who demand evaluation may do so “without recognizing the need to provide financial support or to work with organizations to build their evaluation capacity and expertise” (Hall M. H., 2003).

Outcome based arrangements, including reporting on results, need to be sensitive to the kind of work performed by an agency, to the size of the agency and to the relative capacity of the agency. Implementation of outcome-based arrangements is not an all or nothing proposition. Recognition should be given to the current functioning of the organization and continuous improvement strategies should be put in place to address deficiencies and to move the agency along (Ebrahim A. , 2010).

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 17

Flexibility in Funding and Accountability Arrangements

Funders are seeking ways to increase the participation of recipients of their funds to evaluate their activities and in some cases to share decision-making. Surveys of membership can be seen as a different tool for fulfilling accountability requirements (Ebrahim A. , 2010).

There has a been a move to principle-based funding arrangements that links funding choices to the mission and goals of organizations.

Some agencies should move to assessing long term results while others should remain with assessing shorter-term results (Ebrahim A. V., 2010). Capacity of the organization is a critical factor in making this assessment. The most important challenge is to align the accountability process with the mission and goals of the agency (Ebrahim A. V., 2010). Some agencies are investigating the benefits of flexible funding arrangement including multi-year funding agreements (Leviten-Reid, 2007).

6. External Context

Priorities for the Saskatchewan Parks and Recreation Association

SPRA has developed and approved a Strategic Plan to guide its decisions and actions between

2009 and 2013. Trends, challenges, opportunities, members needs and their commitment to the success of the organization have all contributed to the development of the Strategic Plan.

SPRA’s vision is:

“We are the leader for a parks and recreation network that builds healthy active communities in Saskatchewan.”

SPRA’s mission is:

“We provide leadership and support to enhance the quality of the parks and recreation network.”

Values and roles for the SPRA have also been defined. Values include volunteerism, partnerships, diversity, accountability, collaboration, inclusion, and benefits of parks and recreation. Roles include training, education, advocacy, funding, information management, research and networking.

A number of end statements or strategic directions have been developed to define results and accountabilities to various parties. The following chart summarizes the end statements and the desired outcomes:

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 18

End Statement

The parks and recreation network is coordinated.

There is a strong recreation component throughout the province.

The parks and recreation network is supported.

The network advocates for parks and recreation in

Saskatchewan.

Parks and open spaces are supported.

Recreation facilities are supported.

Outcomes

• Communities are well informed and have access to information.

• The parks and recreation network is linked and responds to common priorities.

• Communication with the parks and recreation network is efficient and two way.

• Aboriginal communities are well informed and have access to information.

• The network is engaged in the development of policy related to recreation and the physical activity movement.

• The network is engaged in the physical activity movement.

• Barriers to participation in recreation are reduced.

• The recreation delivery system operates effectively and efficiently.

• SPRA responds and is receptive to member needs.

• The network has access to training and education.

• Members have access to and knowledge and skills to provide safe environments for recreation services.

• Funding is linked to member needs and trends.

• SPRA is the voice and recognized advocate for parks and recreation.

• People of Saskatchewan are aware of the benefits of parks and recreation.

• Public policy is focused on increasing participation in parks and open spaces and recreation opportunities.

• The network is aware and informed of issues and best practices that are relevant to the field.

• Members are advocating for parks and recreation.

• Public policy supports parks and recreation benefits.

• Members understand the role of SPRA.

• The parks and recreation network has the knowledge, access to resources and skills required to provide quality parks and open spaces.

• Parks practitioners and volunteers are engaged in the parks and recreation network.

• There is an increased awareness of the value of parks and open spaces and the environment.

• The network has the knowledge and access to resources and skills required to provide safe and efficient recreation facilities and services.

• Practitioners and volunteers are engaged in the recreation facility network.

• SPRA supports recreation facilities and operators.

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 19

Priorities of the Government of Saskatchewan

Part of understanding the environment for the recreation sector is appreciating the priorities that the Government of Saskatchewan has defined to guide government actions and investments over the course of its current mandate. Broad goals have been set out by the government which focus on sustaining economic growth for the benefit of Saskatchewan people and ensuring that the province is ready for economic and population growth. In addition, the government plans to secure Saskatchewan as a safe place to live and raise a family, and that Saskatchewan people are confident in their future. Finally, the government intends to fulfil its commitments from the 2007 election.

The Ministry of Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport (TPCS) has defined six broad goals for its mandate:

• Promote tourism development and investment;

• Promote a creative arts and cultural community;

• Promote healthy, active families through sport, culture and recreation;

• Conserve heritage resources;

• Enhance Saskatchewan parks;

• Establish a Provincial Capital Commission.

Premier Wall has directed his Cabinet Ministers to priorize certain activities – one of these priorities for the Minister of TPCS is to work in partnership with Saskatchewan Parks and

Recreation Association to review the provincial recreation sector to identify best practices and growth opportunities, and to establish an evaluation framework to monitor sector outcomes.

TCPS continues to be active in areas that are supportive of the broad community and nonprofit sector. The government has entered into a three year agreement to provide for a

Community Investment Fund (CIF) that uses proceeds from the Saskatchewan Gaming

Corporation to contribute $6.3M annually to grant programs through the CIF. A new program called the Community Vitality Program will receive $1.3M annually to support community capacity and development, starting in 2010. The Community Grant Program and the Urban Aboriginal Grant Program will continue.

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 20

New Priorities

In consideration of the environmental scan a range of strategic priority areas emerge related to the recreation sector:

1) Increase leadership development opportunities and participation levels of First Nations and Metis people in recreation;

2) Improve the leadership skills of youth while increasing the opportunity for youth to develop and practice such skills;

3) Increase the number of Saskatchewan residents that are physically active;

4) Support the establishment and maintenance of recreation environments that provide quality recreation activities; and

5) Improve access to recreation initiatives through barrier reduction.

7. Conclusion

Saskatchewan is undergoing many changes. Our population is growing and changing. It is becoming more diverse, with First Nations people and immigrants assuming a more prominent role in our society. Our province is at the same time increasingly young and old with relatively large populations at each end of the age spectrum. Saskatchewan’s economy has undergone significant changes in recent years. Saskatchewan’s history as a have not province has been erased by a recent record of impressive economic growth that has been accompanied by more jobs, higher wages, higher real estate values, building permit value growth, and public and private sector investment. The streets in our cities are busier, as are our highways. While all areas of Saskatchewan appear to be benfitting from economic and population growth, growth in our cities is outpacing growth outside of our cities and the decades old trend of people moving from rural to urban areas continues.

Public policy makers are increasingly grappling with the challenges of growth instead of the challenges of stagnation or depopulation. Perhaps the most important phenomenon to the provincial psyche is the reversing of a stubborn 25 year trend that saw more people leave than come to Saskatchewan. Since 2007 Saskatchewan has seen more people move in than move out. With Saskatchewan's economic growth has come job growth. Where

Saskatchewan once had more people than jobs, it now has more jobs than people leading to labour market shortages for the first time in recent memory. As labour markets have tightened, employers have become increasingly concerned with attracting and retaining employees. Governments and employers will continue to promote Saskatchewan as a great place to work, live and raise a family. Saskatchewan's parks and recreation sector has a lot to contribute to ensuring that quality of life remains high.

These demographic and economic changes, along with the proliferation of information and communication technologies have precipitated changes in the daily lives of Saskatchewan people. We are busier. We have many more options for our disposable dollars and for our free time. We spend more time in front of the TV and computer. And as a population we exercise less and are more likely to be overweight with nearly ¼ of Saskatchewan residents obese. Perhaps most importantly for the parks and recreation sector, people appear to be

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 21

placing a greater emphasis on leisure time over work. Young people especially place a greater emphasis on their lives outside of work and appear less willing than their parent's generation to work long hours.

These changes are forcing all sectors of our society to behave differently. Educational institutions, employers, builders, and retail sales outlets to name a few are all having to adjust their operations and update plans for the future. The parks and recreation sector is no different. As a responsible public steward the SPRA has initiated a process that will enable it to align its grant funding with emerging strategic priorities in a changing

Saskatchewan. Through the creation of a recreation section plan the SPRA is setting the stage to orient the organizations it funds toward new priorities in Saskatchewan.

Of particular importance to not for profit organizations including those within the parks and recreation sector in Saskatchewan are trends in voluntarism. The agencies offering parks and recreation programming to Saskatchewan people are highly dependent on volunteers for governance, administration and program delivery. Nation leading volunteer rates in

Saskatchewan have enabled organizations to do a good job of delivering programs with modest resources. However, any reduction in volunteer time could present a dilemma for not-for-profit agencies trying to deliver more services to an increasingly diverse population.

As the demographics and economy of the province change, so to have expectations related to accountability. As citizens are demanding greater accountability from their governments, all levels of government are demanding greater accountabilities from agencies receiving public dollars. One consequence of this trend is a general move toward evaluating programs based on their outcomes as opposed to outputs. For small agencies receiving public dollars, increased accountability requirements can quickly become onerous and outstrip an organizations capacity. As SPRA moves toward requiring greater accountability from the organizations that it funds, it will be wise to ensure that higher standards actually deliver meaningful accountability without too great a cost to the grant recipient.

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 22

8. Bibliography

Active Health Kids Canada. (2009). 2009 Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card on Physical

Activitiy for Children and Youth: Saskatchewan Supplement.

Active Healthy Kids Canada.

Canadian Centre for Philanthropy. Philanthropy Tomorrow A Planning Tool for Voluntary

Organizations.

Canadian Council on Social Development. (2003). Funding Matters: The Impact of Canada's

New Funding Regime on Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations.

Canadian Council on Social

Development.

Canadian Index of Wellbeing. (2010). Caught in the Time Crunch: Time Use, Leisure and

Culture in Canada.

Chabun, W. (2010 11-September). Sask. Economy Roaring. Leader Post .

Cravens, S. J. (2000). The Virtual Volunteering Guidebook, How to Apply Principles of Real

World Volunteer Management to Online Service.

The Virtual Volunteering Project, part of the

Charles A. Dana Centre,University of Texas at Austin.

District of West Kelowna. (2009). Parks & Recreation Master Plan: Trends Backgrounder.

District of West Kelowna.

Ebrahim, A. (2010). The Many Faces of Nonprofit Accountability.

Harvard Business School.

Harvard Business School.

Ebrahim, A. V. (2010). The Limits of Nonprofit Impact: A Contingency Framework for

Measuring Social Performance.

Harvard Business School. Harvard Business School.

Elliot, D. (2010a). Construction Labour Market Database.

Unpublished.

Elliot, D. (2010b). Economic Trends in Demographic and Economic Statistics.

Not Published.

Elliot, D. (2010 May). Sask Trends Monitor. XXVII (5).

Elliot, D. (2009 2-June). Sask Trends PARWC June 2.

Retrieved 2010 13-10 from Sask Trends

Monitor: http://www.sasktrends.ca/publications.html

Government of Saskatchewan. (2010 30-September ). From Bureau of Statistics: www.stats.gov.sk.ca

Government of Saskatchewan. (2010a 12-April). News Releases.

From Government of

Saskatchewan: http://gov.sk.ca/news?newsId=6daae237-d2d4-4fec-8b29-e894f5718378

Government of Saskatchewan. (2006). Saskatchewan Population by Age and Sex Report.

From

Bureau of Statistics: http://www.stats.gov.sk.ca/stats/pop/Censusagesex2006.pdf

Hall, M. D. (2009). Caring Canadians, Involved Canadians: Highlights from the 2007 Canada

Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating.

Statistics Canada. Minister responsible for

Statistics Canada.

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 23

Hall, M. H. (2003). Assessing Performance: Evaluation Practices in Canada's Voluntary Sector.

Canadian Centre for Philanthropy and the Centre for Voluntary Sector Research and

Development, Carleton University.

Harper, J. (2008). In Alberta... Recreation and Parks Matter.

Retrieved 10 15, 2010, from

Alberta Recreation and Parks Association: http://www.arpaonline.ca/rr/rr_research.html

HRSDC. (2009 19-March). Volunteering Among Seniors: Presentation for the National

Seniors Council.

Insightrix Research. (2010). Living in Saskatchewan Communities: A Quality of Life Study.

Regina: Community Initiatives Fund.

Keller, G. (2010 23-September ). Canadian obesity high compared to other rich countries: report. Globe and Mail .

Leviten-Reid, E. (2007). Investing in Community Capacity Building.

Caledon Institute of Social

Policy. Caledon Institute of Social Policy.

Potwarka LR, K. A. (2008). Places to Play: Association of Park Space Facilities with Healthy

Weight Status Among Children. Journal of Community Health , 33, 344-50.

RETHINK (West) Inc. (2009). Foresight: Acting on the Trends That Matter. Alberta

Recreation and Parks Association.

Rosella, L. C. (2010). What Does It Take To Make a Healthy Province. Toronto: Parks &

Recreation Ontario.

Smale, B. H. (2010). Leisure adn Culture: A Report of the Canadian Index of Wellbeing.

Candian Index of Wellbeing.

Statistics Canada. (2010 29-September). The Daily: Canada's Population Estimates.

From

Statistics Canada: www.statcan.gc.ca

Struthers, M. (2010). Reflections on Starlings, Collaboratives and the Nature of the Non

Profit Sector. The Philanthropist , 23 (2).

Zarenpoush, F. S. (2007). Effective Knowledge Transfer & Exchange for Non Profit

Corporations A Framework.

Imagine Canada.

SPRA: Recreation Section Plan Environmental Scan 24