JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MOSQUITO CONTROL ASSOCIATION

advertisement

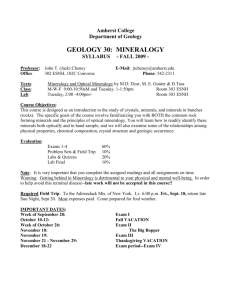

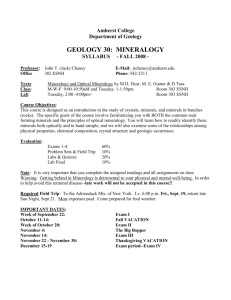

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MOSQUITO CONTROL ASSOCIATION Mosquito News MEMORIAL LECTURE 2011 AMCA MEMORIAL LECTURE HONOREE: DR. HARRISON GRAY DYAR JR. TERRY L. CARPENTER1 AND TERRY A. KLEIN2 Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, 27(3):336–343, 2011 Copyright E 2011 by The American Mosquito Control Association, Inc. MEMORIAL LECTURE 2011 AMCA MEMORIAL LECTURE HONOREE: DR. HARRISON GRAY DYAR JR. TERRY L. CARPENTER1 AND TERRY A. KLEIN2 ABSTRACT. Dr. Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. (1866–1929) was an early-20th-century expert in taxonomy and biology of culicid Diptera. At an early age, Dyar became interested in the biology, life history, and taxonomy of Lepidoptera, which he continued throughout his entire career. Dyar pursued his passion for entomology, and during his formative years, professionals sent Lepidoptera specimens to him for identification. As his prominence was well known to Leland Howard, then the honorary curator of the US National Museum of Natural History, he was asked and accepted the position as honorary custodian of Lepidoptera in 1897, which later included periods of service with the US Department of Agriculture Bureau of Entomology and the US Army Officers’ Reserve Corps. This position went without stipend and it was Dyar’s personal wealth that allowed him to continue his love of entomology. However, the museum did provide limited staff and funds for illustrators, supplies, and travel. In the early 1900s, his interests expanded to include mosquitoes where he concentrated on their life histories and taxonomy. Throughout his career, Dyar often criticized colleagues, both personally and in publications, often with interludes of peace to coauthor articles and books. His legacy of original scientific work is of lasting significance to public health and entomology communities, in recognition of which he was selected as the 2011 AMCA memorial lecture honoree. KEY WORDS Dyar, Lepidoptera, Diptera, Culicidae, mosquitoes, memorial INTRODUCTION Dr. Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. (1866–1929) was a world-renowned expert in the biology and taxonomy of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), Symphyta (sawflies), and nematocerous Diptera, including the mosquitoes (Knight and Pugh 1974, Epstein and Henson 1992). His interest in Lepidoptera is relevant to our memorializing him today because it was that interest which started him on his life’s work as an entomologist. His groundbreaking research in the early decades of the 20th century logarithmically increased knowledge about mosquitoes, shaped our understanding of their importance to man and the environment, and established a firm foundation for mosquito control professionals in the 21st century—see Fig. 1. EARLY LIFE Dyar was born February 14, 1866, in the borough of Manhattan, New York City, the elder of 2 children born to Harrison Gray and Eleanora (Hannum) Dyar, both descendants of old New England families (Dyar 1903, White 1910). Dyar Sr. was an inventor of note, who, by 1 Armed Forces Pest Management Board, Fort Detrick, Forest Glen Annex, c/o 6900 Georgia Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20307-5001. 2 Force Health Protection and Preventive Medicine, 65th Medical Brigade/US Army MEDDAC-Korea, Unit 15281, APO AP 96205-5281. his son’s account, invented the magnetic telegraph independently of Samuel B. Morse but was unable to develop his invention commercially and abandoned the effort to concentrate on interests in chemistry. He earned a substantial fortune from patents for dyestuffs before his death at the age of 70 in 1875, just 10 years after marrying, and left his family in comfortable circumstances. The family fortune would be a significant factor in his son’s professional life. Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. received his early education at the Roxbury Latin School in Boston, MA (Epstein and Henson 1992). Evidence in the records of Rhinebeck, NY, where his father had purchased a family home, indicates that Dyar also attended the DeGarmo Institute, a private high school in Rhinebeck (Kelly 2009). He graduated from Roxbury at the age of 19 in 1885 (White 1910) with advanced standings in mathematics, physics, and French, but interestingly, considering how well he was to apply it in adulthood, lesser success in Latin (Epstein and Henson 1992). As a youth, Dyar was fascinated by butterflies and moths, and in 1882 at the age of 16 (Epstein and Henson 1992) he began keeping detailed rearing and fieldwork records in notebooks, which are now preserved among his papers at the Smithsonian Institution (Lytle 2003). He was most fond of limacodid moths, the larvae of which are known as slug caterpillars, and this interest continued throughout his life (Epstein and Henson 1992). 336 SEPTEMBER 2011 2011 MEMORIAL LECTURE HONOREE Fig. 1. Dr. Harrison G. Dyar Jr., ca. 1917 (Smithsonian Institution Archives, image no. SIA20090002). ACADEMIC PREPARATION After completing secondary school, Dyar entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and studied chemistry, graduating in 1889 with a bachelor of science degree (White 1910). He published his first entomological paper in 1888 (Dyar 1888), a short but characteristically detailed study of the immature stages of the moth Dryopteris rosea (Walker, 1855). In 1892 Dyar entered graduate school at Columbia College (now Columbia University) and earned a master’s degree in biology in 1894, with a thesis on the classification of lepidopterous larvae (White 1910). He stayed on at Columbia to earn a Ph.D. in 1895, majoring in bacteriology and writing a thesis on airborne bacteria (White 1910), but minoring in entomology (Epstein and Henson 1992). After graduation, he took a position as Assistant Bacteriologist at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (White 1910). PROFESSIONAL CAREER While teaching at Columbia from 1895 to 1897, Dyar continued his entomological pursuits, further developing his expertise in the biology and taxonomy of Lepidoptera and Symphyta (Smith 1986, Epstein and Henson 1992). In 1897, Dr. 337 Leland O. Howard, chief of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Bureau of Entomology and honorary curator of the US National Museum (USNM), invited Dyar to take the position of honorary custodian of Lepidoptera at the USNM. The position didn’t offer direct compensation (Epstein and Henson 1992), but Dyar accepted, resigned his faculty appointment at Columbia, and moved to Washington, DC, supporting himself with his inherited personal fortune (White 1910, Howard 1930, Epstein and Henson 1992). He purchased 2 adjoining houses in the District, at 1510 and 1512 21st Street NW, several miles north of the museum, settling his family into 1512 and using 1510 for a laboratory. Several years after moving to Washington, Dyar developed a new interest—mosquitoes. Howard relates that Dyar first became interested in mosquitoes in the summer of 1902, when he read Howard’s recently published (Howard 1901) book on mosquitoes. Dyar began studying the markings and structure of mosquito larvae, and ‘‘thus began his work with this group which lasted until the time of his death’’ (Howard 1933). Mosquitoes soon became his primary interest. Working from Monday through Saturday each week, he identified a steady stream of specimens coming into the USDA and USNM as mosquitoes became an increasingly important public health concern in the early 1900s. In addition to fulfilling his identification duties, he was instrumental in acquiring several large collections important to the growth of the museum and its ability to address the needs of the scientific community at large (Epstein and Henson 1992). His personal wealth made it possible for him to travel and collect extensively in North and Central America, to the enormous benefit of the USNM and entomology community. He also added to the collection through specimens he reared in the house he bought adjoining his family home, at 1510 21st Street NW, in Washington, DC (Howard 1930, Epstein and Henson 1992). Dyar was so crucial to the museum’s mosquito work that when he was traveling Howard would forward specimens cross-country for him to identify. On one occasion, when Dyar was planning an extended trip to Panama, Howard wrote, ‘‘I am sorry that from April 1st to September 1st the mosquitoes of most of the United States will be in confusion. No one—not even the mosquitoes themselves—will know their names; and this may react disastrously on the public’’ (Epstein and Henson 1992). In his entomological work, Dyar enjoyed ‘‘lively debate’’ with his colleagues. He was confident in his knowledge, passionate about his beliefs, and fearless in putting forth his opinions. He did not shy away from confrontations with others, whether they were considered his professional superiors or not (Epstein and Henson 338 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MOSQUITO CONTROL ASSOCIATION 1992). Some recipients of his critiques simply ignored him, others responded vigorously in kind. Some who struck back chose creative venues, such as the satirical poem entitled ‘‘When Dyar’s List Comes Out,’’ published by a colleague in 1902 (Newcomb 1902). One of Dyar’s most noteworthy foes was Dr. Clara Southmayd Ludlow, a mosquito taxonomist for the US Army working at the Army Medical Museum nearby in Washington, DC (Carpenter 2005). Ludlow had 2 decades of experience and a Ph.D. degree from Georgetown University, and she was every bit as self-confident and articulate as Dyar. She did not respond meekly to his belittling her and her work; on the contrary, she ably defended herself (Kitzmiller and Ward 1987). Despite their public disagreements, Dyar and Ludlow published 3 papers together (Dyar and Ludlow 1921a, 1921b, 1922), but the volatile exchanges that characterized Dyar’s professional relations with many of his colleagues sometimes caused difficulties in his career (Epstein and Henson 1992). His witty and incisive repartee with colleagues certainly enlivened the scientific journals of the day (Epstein and Henson 1992), and is one of the reasons he is so well remembered. Dyar’s clashes with colleagues gave rise to a story that has been repeated often enough over the years to become mythological in proportions. The story relates that one of Dyar’s entomologist enemies named a genus of moths Dyaria, pronounced like the infamous illness diarrhea, to spite him (Spilman 1984). In fact, in 1893, Dyar’s friend and fellow lepidopterist Berthold Neumoegen did describe a new genus that he named Dyaria after his ‘‘faithful co-labourer and friend Mr. H.G. Dyar’’ (Neumoegen 1893). Pronunciation did not seem to present an issue for either of them, perhaps because they pronounced the genus name ‘‘dyar-eye-a’’ rather than ‘‘dyar-ee-a.’’ Neumoegen placed the new genus in the family Liparidae, but in 1900 Dyar referred it the family Pyralidae, subfamily Epipaschiinae, and synonymized it with the genus Alippa, described by Aurivillius in 1894 (Dyar 1900). Alippa, and therefore Dyaria, were later shown to be junior synonyms of the genus Coenodomus, described by Walsingham in 1889 (Solis 1992), so the genus name Dyaria is no longer in common use. Dyar was on the government payroll as an employee of the USDA Bureau of Entomology for some of the years he worked at the USNM, with the title of ‘‘expert’’ and an annual salary of $1,800—about $22,000 in 2011 dollars (Epstein and Henson 1992). To supplement his government funding, he engaged in commercial consulting on mosquito control efforts, espousing views on surveillance and control in national parks that were decades ahead of their time (Epstein and VOL. 27, NO. 3 Henson 1992). As an example of his thinking, we provide a quote that we believe Dr. Dyar would have delighted in delivering to this audience. During his time as a consultant on mosquito control in national parks, he came to believe that money was being wasted on the application of oil to control nonpest species, on applications in places where mosquitoes did not breed, and on unnecessary 2nd applications—concerns to which we can all relate today. Dyar wrote to his friend L. O. Howard: ‘‘You know there is nothing I like less than killing mosquitoes. The mosquitoes are the subject of my interest, not their absence, and so I feel that all anti-mosquito work is directly detrimental to my special interest. I love to see the mosquitoes in vast swarms, and if I had my way, all the oil would be poured over the human exterminators.’’ Though some might now count themselves among the pantheon of distinguished targets of Dyar’s acerbic wit, we certainly concur with his reasoning concerning the control methods in use at the time. In 1924 Dyar’s background in the study of mosquitoes was the basis for his selection to be commissioned a captain in the Sanitary Department of the US Army Officers’ Reserve Corps (Knight and Pugh 1974, Epstein and Henson 1992), attached to the Army Corps of Engineers (M. R. Dyar, personal communication). He was one of a very small and select group—records indicate that only 14 army entomologists were commissioned in the reserves in the period between World War I and World War II (Shultz 1992). Published records don’t provide details about his duties, but descendants believe he used the accompanying stipend to advance his entomological life-history studies (M. R. Dyar, personal communication). His primary workplace remained the USNM, where he was among his peers—see Fig. 2. Dyar’s interest in the immature stages of insects continued throughout his career. He wrote numerous papers that included detailed descriptions of mosquito larvae, and 3 that dealt exclusively with them: 2 as sole author, ‘‘A synoptic table of North American mosquito larvae’’ (Dyar 1905) and ‘‘Key to the known larvae of the mosquitoes of the United States’’ (Dyar 1906), and 1 as senior author, ‘‘The larvae of Culicidae classified as independent organisms’’ (Dyar and Knab 1906). While observing the immature stages of Lepidoptera in life-cycle studies, he noted that the head capsule widths of larvae followed a geometric progression in growth through successive instars. In a paper published in 1890, he described this phenomenon and its principles, which became known as Dyar’s SEPTEMBER 2011 2011 MEMORIAL LECTURE HONOREE 339 Fig. 2. Dyar with his colleagues at the US National Museum, May 21, 1925 (Smithsonian Institution Archives, image no. 84-3567). Left to right, standing: Arthur Burton Gahan, Charles Tull Greene, William Schaus, Adam Giede Boving, Andrew N. Caudell, William M. Mann, Henry Ellsworth Ewing, Harrison Gray Dyar (arrow), Eugene Schwartz, Sievart Allan Rohwer, Leland Ossian Howard, Ray Shannon, W. Samuel Fisher, Herbert Spencer Barber, unidentified, Robert Asa Cushman, Mrs. A. C. Willis; kneeling: Mildred (Sheilds) Everhart, Eleanor Armstrong, Janice Kyser, Frances (Kaufmann) Appleby, Carol [no surname given], unidentified, Mrs. Yates; seated: Miss Sellins, Mathilde M. Carpenter, Eunice Myers, and Nettie Grochek. Law, or Dyar’s Rule (Dyar 1890). Although initially based on observations of Lepidoptera larvae, Dyar’s Law applies to immature insects in general and is widely used in entomological studies to discern instars of immature insects, to predict the size of instars missing from samples, and other applications. His work on adult insects was equally significant, culminating in his landmark revision of mosquito classification, Mosquitoes of the Americas, published in 1928 (Dyar 1928). Fusing his knowledge of larval and adult stages, Dyar pioneered the use of adult and immature morphological characters (Epstein and Henson 1992), a new approach that became the standard, and is still the classical method. When the Carnegie Institution of Washington provided a grant to Leland O. Howard for the preparation of a monograph on the mosquitoes of the New World, Dyar and Frederick Knab were chosen to assist with the task (Lytle 2003). Dyar and Knab in collaboration are primarily responsible for the taxonomic portions of the comprehensive 4volume work that resulted, Mosquitoes of North and Central America and the West Indies (Howard et al. 1912–1917). Dyar maintained a constant publication stream, authoring a total of 208 papers, reports, books, and other contributions concerning mosquitoes during the period 1901– 1929 (Knight and Pugh 1974). In addition to his museum work, Dyar was editor of one of the great entomological journals of his day, the Journal of the New York Entomological Society, from 1904 to 1907, and he served on the editorial board of the Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington from 1908 to 1912 (Epstein and Henson 1992). In 1913 he started up his own journal, Insecutor Inscitiae Menstruus, which was devoted primarily to Lepidoptera at the outset, but developed considerable involvement with mosquito taxonomy in its prime years (Knight 1974). The title can be loosely translated as Monthly Persecutor of Ignorance, a name ‘‘with attitude,’’ like its creator, though he 340 Table 1. JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MOSQUITO CONTROL ASSOCIATION VOL. 27, NO. 3 Disease vector status of mosquitoes originally described by Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. and collaborators (Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit 2011). Species Aedes angustivittatus Dyar and Knab, 1907 Ae. infirmatus Dyar and Knab, 1906 Ae. melanimon Dyar, 1924 Anopheles bellator Dyar and Knab, 1906 An. neivai Howard, Dyar, and Knab, 1912 An. punctimacula Dyar and Knab, 1906 Culex erythrothorax Dyar, 1907 Cx. ocossa Dyar and Knab, 1919 Cx. taeniopus Dyar and Knab, 1907 Deinocerites pseudes Dyar and Knab, 1909 Haemagogus janthinomys Dyar, 1921 Hg. leucocelaenus (Dyar and Shannon, 1924) Vector status Ilheus virus has been isolated from Ae. angustivittatus collected near Almirante, Panama, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus in Colombia Eastern equine encephalitis (EEE), Keystone, Trivittatus, and Tensaw viruses have been isolated from Ae. infirmatus Vector of Western equine encephalomyelitis (WEE) virus and West Nile virus (WNV) Primary vector of malaria in southeastern Brazil and Trinidad Primary vector of malaria in the coastal south of Buenaventura, Colombia, and has been found infected with yellow fever virus in Panama, and Guaroa virus in Colombia Vector of malaria Vector of WEE virus and WNV Vector of WEE and has the potential to be a very important vector of VEE VEE virus has been isolated from this species, and it is also considered a vector of several Bunyaviruses, including Ossa, Guama, Ananindeua, Bimiti, Mirim, and Guaratuba viruses Vector of VEE and St. Louis encephalitis viruses in laboratory studies Primary vector of sylvan yellow fever endemic in several regions of South America Yellow fever and Una virus have been isolated from Hg. leucocelaenus in Brazil noted in the inaugural issue that ‘‘[t]he title of our publication need not be considered to have any personal application. We endeavor to dispel, to some degree, our general ignorance of the forms of insect life by descriptions of species and genera, life-histories, and other pertinent facts’’ (Dyar 1913). Creating his own journal gave him freedom from page limitations and disagreeing editors, allowing him to publish more papers with less compromising of his original thought. As publisher and editor, he produced 14 volumes, ceasing publication in 1926. LEGACY Dyar was spending his usual Saturday at the National Museum on January 19, 1929, when he suffered a stroke at his desk. He was hospitalized for treatment but died 2 days later on January 21, 3 wk short of his 63rd birthday (Epstein and Henson 1992). He had become so well known for his mosquito work that The New York Times and The Washington Post both produced formal obituaries, headlining his expertise in mosquitoes (Anonymous 1929a, 1929b). His lifelong friend Leland Ossian Howard eulogized him at the annual meeting of the New Jersey Associated Executives in Mosquito Control Association in February 1929 with these words: ‘‘It will be years, I fear many years, before he can be replaced by an American worker of even approximate knowledge and qualifications’’ (Patterson 2009). Dyar’s personal life has been the subject of considerable writing, some of it inaccurate and unjustly sensationalized. His 1st marriage, on October 15, 1889, in Los Angeles, CA, was to Zella Peabody (White 1910), and his 2nd, on April 26, 1921, in Reno, NV, was to Wellesca (Pollock) Allen (Engle 2003). By his 1st marriage, Dr. Dyar had a daughter, Dorothy, and a son, Otis P., and by his 2nd marriage he had 3 sons, Roshan W., Harrison G., and Wallace J. Dyar. His descendants have followed varied walks of life, and Dyar remains the only entomologist in the family tree. At the memorial lecture in March 2011, we were honored by the presence of 2 of Dr. Dyar’s grandchildren, Michael R. Dyar, who is a naturalist at Yosemite National Park, and Sharon Dyar Hopkins, who is a retired executive living in North Carolina. Their father was Dr. Dyar’s 1st son by his 2nd marriage, Roshan W. Dyar. For the most part, Dyar’s biographers fail to capture the truths behind the legends surrounding Dyar, with 1 prominent exception—an exquisitely researched biography produced by Dr. Marc Epstein and Dr. Pamela Henson of the Smithsonian Institution (Epstein and Henson 1992). It accurately covers the many facets of Dyar’s public and personal life, setting his life in the context of the time and the people with whom he worked and lived, and provides the truest portrayal of him as a person as well as a professional; their article should be consulted by anyone with an interest in Dyar’s more personal side. Dyar’s legacy for the American Mosquito Control Association community is manyfold. He brought his intelligence and analytic ability to bear on mosquitoes during the time when they SEPTEMBER 2011 2011 MEMORIAL LECTURE HONOREE Table 2. Patronyms honoring Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. These patronyms are presented in their original epithet form to illustrate the breadth of Dyar’s influence among insect taxonomists. Diptera (16) Cecidomyiidae Lestremia dyari Felt, 1908 Chironomidae Tanytarsus dyari Townes, 1945 Tanypus dyari Coquillett, 1902 Corethrellidae Corethrella dyari Lane, 1942 Culicidae Culex dyari Coquillett, 1902 Deinocerites dyari Belkin and Hogue, 1959 Genus Dyarina Bonne-Wepster and Bonne, 1921 Mansonia dyari Belkin, Heinemann, and Page, 1970 Psorophora dyari Petrocchi, 1927 Tripteroides dyari Bohart and Farner, 1944 Wyeomyia dyari Lane and Cerqueira, 1942 Dixidae Dixa dyari Garrett, 1924 Limoniidae Erioptera dyari Alexander, 1924 Phoridae Aphiochaeta dyari Malloch, 1912 Simuliidae Subgenus Dyarella Vargas, Martı́nez Palacios, and Dı́az Nájera, 1946 Syrphidae Sphecomyia dyari Shannon, 1925 Hymenoptera (10) Braconidae Orthostigma dyari Fischer, 1969 Diprionidae Neodiprion dyari Rohwer, 1918 Encyrtidae Anagyrus dyari Girault, 1915 Ichneumonidae Crypturus dyari Ashmead, 1897 Tenthredinidae Amauronematus dyari Marlatt, 1896 Blennocampa dyari Benson, 1930 Hemichroa dyari Rohwer, 1918 Macrophya dyari Rohwer, 1911 Pristiphora dyari Marlatt, 1896 Pteronus dyari Marlatt, 1896 Lepidoptera (43) Acrolophidae Amydria dyarella Dietz, 1905 Arctiidae Agylla dyari Beutelspacher, 1983 Callimorpha lecontei dyarii Merrick, 1901 Choreutidae Choreutis dyarella Kearfott, 1902 Hemerophila dyari Busck, 1900 Crambidae Diatraea dyari Box, 1930 Evergestis dyaralis Fernald, 1901 341 Table 2. Continued. Gelechiidae Gelechia dyariella Busck, 1903 Geometridae Antepione dyari Grossbeck, 1916 Eupithecia dyarata Taylor, 1906 Gabriola dyari Taylor, 1904 Nemoria dyarii Hulst, 1900 Pero dyari Cassino and Swett, 1922 Sabulodes dyari Grossbeck, 1908 Gracillariidae Chilocampyla dyariella Busck, 1900 Lasiocampidae Gastropacha dyari Rivers, 1893 Tolype dyari Draudt, 1927 Limacodidae Epiperola dyari Dognin, 1910 Phobetron dyari Barnes and Benjamin, 1926 Lymantriidae Genus Dyaria Neumoegen, 1893 Megalopygidae Macara dyari Dognin, 1914 Megalopyge dyari Hopp, 1935 Mesoscia dyari Schaus, 1912 Podalia dyari Joicey and Talbot, 1922 Noctuidae Acanthermia dyari Hampson, 1926 Cirrhophanus dyari Cockerell, 1899 Eriopyga dyari Draudt, 1924 Euclidia dyari Smith, 1903 Eutelia dyari Draudt, 1939 Stiria dyari Hill, 1924 Notodontidae Azaxia dyari Schaus, 1911 Hemiceras dyari Strand, 1911 Hemipecteros dyari Schaus, 1920 Nymphalidae Lymanopoda dyari Pyrcz, 2004 Phyciodes tharos dyari Gunder, 1928 Phycitidae Promylea dyari Heinrich, 1956 Pyralidae Acrobasis dyarella Ely, 1910 Saturniidae Agapema anona dyari Cockerell, 1914, ‘‘Dyar’s Silk Moth’’ Genus Eudyaria Grote, 1896 Euleucophaeus dyari Draudt, 1930 Sesiidae Aegeria tibialis dyari Cockerell, 1908 Tortricidae Enarmonia dyarana Kearfott, 1907 Zygaenidae Tetraclonia dyaria Jordan, 1913 Neuroptera (1) Hemerobiidae Hemerobius dyari Currie, 1904 342 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MOSQUITO CONTROL ASSOCIATION were first receiving major attention as disease vectors, and became a pioneer in mosquito systematics. His revisions of higher classifications, descriptions of species in 3 taxonomic orders, and the collections of specimens he amassed, all form a body of work valuable to the profession of entomology. He was an acutely observant chronicler of mosquito biology, and his detailed life-history studies are of tremendous value. Dyar, alone or with collaborators, described some 661 new mosquito species, of which 221 (33.4%) are currently valid (Wilkerson, personal communication). Of these, 12 species have medical significance—see Table 1. Dyar and collaborators Frederick Knab and Raymond Shannon described 6 species in the genus Toxorhynchites (Tx. gigantulus Dyar and Shannon 1925, Tx. guadeloupensis Dyar and Knab 1906, Tx. moctezuma Dyar and Knab 1906, Tx. nepenthis Dyar and Shannon 1925, Tx. rutilus septentrionalis Dyar and Knab 1906, and Tx. theobaldi Dyar and Knab 1906), which are of interest because of their potential for biological control. Toxorhynchites larvae are predacious on larvae of other mosquito species, and adult females as well as males do not bite humans or other animals, and feed exclusively on nectar and other sugary substances, characteristics appropriate to Dr. Dyar’s forward-thinking environmental consciousness. Dyar has been honored many times over the years by his colleagues through the bestowal of some 70 patronyms—see Table 2. The total has been somewhat reduced by synonymies over the years, but the original intent illustrates the breadth as well as the depth of Dyar’s work in the entomological community. Of the mosquitoes named in Dyar’s honor, 2 have medical significance: Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus has been isolated from Mansonia dyari Belkin, Heinemann, and Page, 1970, and Deinocerites dyari Belkin and Hogue, 1959, though neither is strongly anthropophilic so their potential for involvement as vectors of human disease is limited. In summary, Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. has been honored many times over the years by his colleagues, through the patronyms, praise, and poignant recollections. Today, we honor him for his seminal contributions to culicidology, and for his contributions that extend beyond mosquitoes and mosquito bionomics to the broader field of public health entomology. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to express our deepest appreciation to Dafydd N. Dyar, Sharon Dyar Hopkins, and Michael R. Dyar for kindly sharing their personal Dyar family knowledge and sup- VOL. 27, NO. 3 porting the research into their grandfather’s life so essential to the memorial process. We thank Richard Robbins of the Armed Forces Pest Management Board, Richard Wilkerson of the Walter Reed Biosystematics Laboratory, and Mary Markey, Ellen Alers, and Tad Bennicoff of the Smithsonian Institution for their individual support, and the professional staffs of the Library of Congress and the National Agricultural Library for their general assistance in acquiring works consulted for the preparation of this memorial. We thank Captain Stanton Cope, US Navy, Medical Service Corps, Director of the Armed Forces Pest Management Board, Washington, DC, for his constant support and encouragement from concept through completion of this memorial. REFERENCES CITED Anonymous. 1929a. Dr. H. G. Dyar dies; a noted biologist; recognized as the foremost authority on American mosquitoes. The New York Times, 1929 Jan 22; 24 p. Anonymous. 1929b. Services for Dr. H. G. Dyar, mosquito expert, tomorrow, famed U.S. entomologist succumbs to attack of paralysis. The Washington Post, 1929 Jan 23; 4 p. Carpenter TL. 2005. Notes on the life of Dr. Clara Southmayd Ludlow, Ph.D., medical entomologist (1852–1924). Proc Entomol Soc Wash 107:657–662. Dyar HG. 1888. Partial preparatory stages of Dryopteryx rosea, Wlk. Entomol Am 4:179. Dyar HG. 1890. The number of molts of lepidopterous larvae. Psyche 5:420–422. Dyar HG. 1900. Note on the genus Dyaria Neum. Can Entomol 32:284. Dyar HG. 1903. A preliminary genealogy of the Dyar family. Washington, DC: Gibson Brothers, Printers and Bookbinders. Dyar HG. 1905. A synoptic table of North American mosquito larvae. J N Y Entomol Soc 13:22–26. Dyar HG. 1906. Key to the known larvae of the mosquitoes of the United States. USDA Bureau of Entomology Circular 72. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture. Dyar HG. 1913. Editor’s foreword. Insec Inscit Menst 1:1. Dyar HG. 1928. The mosquitoes of the Americas. Carnegie Institution Publication 387. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington. Dyar HG, Knab F. 1906. The larvae of Culicidae classified as independent organisms. J N Y Entomol Soc 14:169–230. Dyar HG, Ludlow CS. 1921a. Two new American mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae). Insec Inscit Menst 9:46–50. Dyar HG, Ludlow CS. 1921b. A note on two Panama mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae). Mil Surg 48:677– 680. Dyar HG, Ludlow CS. 1922. Notes on American mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae). Mil Surg 50:61–64. Engle R. 2003. George Freeman Pollock and Stony Man Camp. Shenandoah Natl Park Resour Manage Newsl 1:21–24. Epstein ME, Henson PM. 1992. Digging for Dyar, the man behind the myth. Am Entomol 38:148–169. SEPTEMBER 2011 2011 MEMORIAL LECTURE HONOREE Howard LO. 1901. Mosquitoes: how they live; how they carry disease; how they are classified; how they may be destroyed. New York, NY: McClure, Phillips & Co. Howard LO. 1930. Harrison Gray Dyar. In: Johnson A, Malone D, eds. Dictionary of American biography. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p 578–579. Howard LO. 1933. Fighting the insects, the story of an entomologist. New York, NY: Macmillan Co. Howard LO, Dyar HG, Knab F. 1912–1917. The mosquitoes of North and Central America and the West Indies. Volumes 1–4. Washington, DC: The Carnegie Institution of Washington, DC. Kelly N. 2009. Linwood Hill, new information about an eccentric resident. Rhinebeck (New York) Hist Soc Newsl [Internet] Winter issue:1–3 [accessed January 9, 2011]. Available from: http://www.scribd.com/doc/ 37166894/Nov-Newsletter. Kitzmiller JB, Ward RR. 1987. Biography of Clara Southmayd Ludlow 1852–1924. Mosq Syst 19:251–258. Knight KL. 1974. Editor’s corner. Mosq Syst 7:297. Knight KL, Pugh RB. 1974. A bibliography of mosquito writings of H. G. Dyar and Frederick Knab. Mosq Syst 6:11–26. Lytle RH. 2003. Record unit 7101, Harrison Gray Dyar papers, 1882–1927; Finding aids to personal papers and special collections in the Smithsonian Institution archives [Internet]. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution [accessed December 5, 2010]. Available from: http:// siarchives.si.edu/findingaids/FARU7101.htm. 343 Neumoegen B. 1893. Description of a peculiar new liparid genus from Maine. Can Entomol 25:211–215. Newcomb HH. 1902. When Dyar’s list comes out. Entomol News 13:263–264. Patterson GM. 2009. The mosquito crusades, a history of the American anti-mosquito movement from the Reed Commission to the first Earth Day. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press. 120 p. Shultz HA. 1992. 100 years of entomology in the Department of Defense. In: Adams JR, ed. Insect potpourri: adventures in entomology. Gainesville, FL: Sandhill Crane Press, Inc. p 61–72. Smith DR. 1986. The sawfly work of H. G. Dyar (Hymenoptera: Symphyta). Trans Am Entomol Soc 112:369–396. Solis MA. 1992. Check list of the Old World Epipaschiinae and the related New World genera Macalla and Epipaschia (Pyralidae). J Lepid Soc 46:280–297. Spilman TJ. 1984. Vignettes of 100 years of the Entomological Society of Washington. Proc Entomol Soc Wash 86:1–10. Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit. 2011. Medically important mosquito species [Internet]. Suitland, MD: Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit [accessed January 10, 2011]. Available from: http://www.wrbu.org/. White JT, ed. The national cyclopaedia of American biography. Volume 14, Suppl. I. New York, NY: James T. White & Co. 97 p.