Advertising Decisions and Children's Product Categories

advertisement

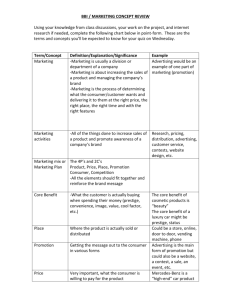

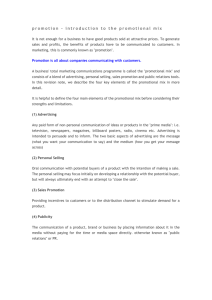

Advertising Decisions and “Children’s” Product Categories Eileen Bridges, Richard A. Briesch, and Chi Kin (Bennett) Yim August 2004 Eileen Bridges is Associate Professor of Marketing, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242. Richard A. Briesch is Assistant Professor of Marketing, College of Business Administration, Southern Methodist University. Chi Kin (Bennett) Yim is Associate Professor of Marketing, School of Business, The University of Hong Kong. The authors are listed alphabetically, as all three contributed equally to this study. We thank Ed Fox, Roger Kerin, and Amna Kirmani for helpful comments and A.C. Nielsen Company for providing data. Advertising Decisions and “Children’s” Product Categories ABSTRACT When products are designed for the youth market, should marketers advertise to parents who might make the purchase decision? Or does it make more sense target children directly? In the latter case, marketers tend to rely on the “nag factor,” reaching children so they will influence their parents’ purchase decisions. For product categories aimed at children, this study observes no difference in response to promotional activities (temporary price cuts, in-store displays, and feature advertisements) between households with children and those without. However, the findings provide indirect evidence that media advertising is effective in driving children’s requests for carbonated beverages and children’s breakfast cereal. Further, households with children show greater sensitivity to price in these product categories than do households without children. Thus, the public policy debate over whether advertising to children is appropriate is shown to be driven by a very real influence on buying. However, because advertising messages cannot be completely stopped from reaching children, if the goal of public policy is to promote healthy eating and reduce child obesity, it may be more effective to implement taxes that activate a price response in children’s food categories. KEYWORDS: Advertising, Target Marketing, Children, Public Policy 1 INTRODUCTION We wish to improve understanding of how consumers’ response to promotional activities might depend on whether the product category is intended primarily for adults or for children, and how such response might differ in households with and without children. Advertising directed at adults, for adult products, tends to aim at building brand loyalty, focusing on product characteristics that are perceived to be of long-term value. Children’s products, on the other hand, must be updated frequently, reflecting the latest theme or character in order to grab attention. Advertising aimed at children does not focus on brand loyalty, but on the new and exciting features and tie-ins that are available. Typically, purchases are made by adult consumers, regardless of whether the product category is targeted primarily for adults or children. Thus, advertising for adult products is aimed directly at the decision maker / buyer, but for children’s products, the path to purchase is less direct. When children wish to influence a purchase, they often utilize a mechanism termed the “nag factor,” which describes this indirect path: promotional activities influence children, who request that their parents buy the product, and then the parent makes the decision and/or purchase. Consumer goods manufacturers recognize the possibility that the nature of the product category might influence promotional effectiveness. An interview with an analyst at a major consumer goods firm (Foley 2002) indicates that promotional decisions depend on whether the product category is aimed toward children or adults. He states “ketchup and peanut butter appeal more to children based on the function of the condiment. Both are used as food enhancers rather than staple products. Children don’t think of tuna as a ‘fun food,’ but rather as a nutritional food. Children want to make their food fun and interesting. Ketchup is used on burgers, hot dogs, fries, and other foods that are associated with carefree eating.” Although the 2 company already looks at demographic differences in product choice and response to promotion, Foley expresses a need to better understand how the nature of the product category influences promotional effectiveness. Within the broad group we describe as products aimed at children, further distinction may be useful. Specifically, when product categories and advertising messages are aimed at young children, brand appeals offer a constant stream of new characters, bonus offers, movie tie-ins, and premiums (Dalmeny 2003). This young audience does not necessarily understand the purpose of advertising, and they may trust messages that imply unhealthy foods are good for you (Issue Brief 2004). Further, they do not develop brand loyalty, and they request whatever brand offers the latest appeal that reaches them. Thus, their response to advertising appears as frequent brand switching. Teenagers, on the other hand, are beginning to shop more like adults; they respond to image-oriented messages and develop brand loyalties (Kelly, Slater, and Karan 2002). Thus, when advertising is effective with older children, the impact may appear as a decrease in brand switching. In addition to considering the dual impacts of product category characteristics and brand-level promotional activities, we wish to describe how the presence of children in a household might influence purchases made. This is important because the nag factor cannot be influential if no children are present in the household to make brand purchase requests. We propose that consumer sensitivity to promotions depends on both the tendency of the product category to be targeted for children or adults, and the presence or absence of children in the buying households. We develop propositions, discuss modeling and empirical testing, and report our results. Finally, we conclude with managerial and public policy implications, limitations, and directions for future research. 3 MOTIVATION Effectiveness of Promotional Activities A long stream of research in marketing considers the costs and benefits of various promotional activities. Most early studies of promotional response assumed the impact of these activities to be homogeneous (see Guadagni and Little 1983), so any differential effects of temporary price reductions, in-store displays, and feature advertisements were not identified. However, as the research stream developed, cross-sectional variations in consumer response to different types of promotions began to be observed across product categories, markets, and households (Bucklin and Gupta 1992, Fader and Lodish 1990, Grover and Srinivasan 1992, Inman and McAlister 1993, Kamakura and Russell 1989, Narasimhan, Neslin, and Sen 1996). As marketers began to look at longitudinal effects, researchers noted that price promotions could have adverse effects on consumers’ brand choice behavior by making them more sensitive to price (Boulding, Lee, and Staelin 1994, Mela, Gupta, and Lehmann 1997, Papatla and Krishnamurthi 1996). Neslin (2002, p.17) also finds that, over time, non-price promotions may influence price sensitivity, and concludes, “there is fairly strong evidence that promotions affect price or promotion sensitivity.” It is important to recognize that the efficacy of promotional activities may depend on a complex interaction between consumers, the brands, and the specific promotions offered. For instance, smaller households with higher incomes are found to be less responsive to temporary price cuts and other promotions (Gupta and Chintagunta 1994). Indeed, Fader and McAlister (1990) note that some consumers seek out promotions for preferred brands. These examples are consistent with research by Heilman, Bowman, and Wright (2000), which indicates that certain consumer characteristics and elements of purchase history may influence response to promotional offers. 4 The Role of Product Category Because retail managers for packaged goods must make decisions regarding the type and quantity of promotion for a specific brand (as opposed to for a specific customer), it is important to consider differences in promotional response by product category. Thus, in addition to asking, “how do households with children tend to respond to various promotional activities?” we must consider “how do consumers, in general, respond to promotion of a childoriented product?” Although both questions are relevant, the answer to the latter question will be more helpful to the manager who needs to make a decision by brand or product category. In the present research, we look specifically at two categories that are selected by and for adults and two where children often influence choice. We note that, while it is typically the adult that makes the decision to purchase, children tend to influence the buying decision in product categories designed for children. Research suggests that children have less clearly developed brand preferences than do adults, and that they are less consistent in terms of their brand choices (Bahn 1986). This may be due to the fact that adults have more sophisticated categorization ability, while younger consumers’ apparent inconsistency may be due to lack of a frame of reference (John and Lakshmi-Ratan 1992). Thus, we might anticipate that children would be more influenced by promotional activities than would adults. This is consistent with the findings of Atkin (1978) and Ryans (1980); further, John (1999, p.200) notes that “children have the most influence over purchases of child-relevant items (e.g. cereal).” The literature on children’s preferences can be contrasted with the extant modeling literature, which finds correlational relationships between marketing mix variables and consumer preferences and/or state dependence (e.g., Krishnamurthi and Raj 1991; Seetharaman, Ainslie, and Chintagunta 1999) in product categories normally 5 targeted toward adults. Thus, we consider how promotional response varies depending on whether the primary target market for the product category is children or adults. Variety Seeking When consumers switch brands on the majority of their purchase occasions, it may not be due to either price or available promotions. Instead, some consumers are thought to make dynamic choices due to a desire for change. This is called “variety seeking” behavior (McAlister and Pessemier 1982). More specifically, variety seeking may be characterized as: (1) true, because it is due to the consumer’s desire for a change of pace, (2) developmental, because it comes through buying different brands in order to learn preferences, or (3) illusory, where there are several people in a household, each of whom is loyal to a different brand. The latter type of household appears to seek variety due to its purchase patterns, but each brand actually satisfies the inertial behavior of a different user. In addition, apparent variety seeking behavior may actually be induced by a brand’s promotional activities (temporary price cuts, in-store displays, feature advertisements and media advertising). We consider how children might respond directly or indirectly to such promotions – in particular, it seems unlikely that children would respond to either price deals or feature advertisements, because they do not pay attention to either, but they might influence purchase due to in-store displays. A further test is less direct: as time between purchases increases, consumers and their children have more time to see media advertising and be influenced to switch brands (resulting in apparent variety seeking). Finally, there may be a relationship between price sensitivity and variety seeking; for instance, Kahn and Raju (1991) find that, for major brands, price deals have a greater effect on variety seekers than on inertial households. 6 The Nag Factor The nag factor describes children’s persistent requests that influence parents’ purchases of clothing, shoes, fast food, food to prepare and eat at home, and prepared food items including breakfast cereal, confectionary, beverages, savory snacks, and sweet snacks, which may be chilled or frozen. A study by Western International Media (see Dolliver 1998) indicates that 55% of children age 3-8 request cereals and 53% ask for snacks. According to Dolliver, such requests are more effective when they focus on the importance of having the item, rather than on a high level of repetition. Rose, Boush, and Shohom (2002) also study the presence of children age 3-8 during purchases of breakfast cereals and snack foods, noting that they may be encouraged to learn to make independent choices, guided by adult input. In fact, children often influence purchases besides candy and cereal, and parents may appreciate their input, especially if it makes shopping more efficient (Embrey, 2004). Which product categories tend to be most influenced by the nag factor? One in three visits to a fast food restaurant in 2003 may be attributed to the nag factor, up from one in ten in 1977 (Spake, 2003). Food marketing expenditures aimed at children increased from $6.9 billion in 1992 to $15 billion in 2002 – this includes advertising for such items as cheese crackers, pasta, cereal, sweetened snacks, Oscar Mayer “Lunchables,” and Kellogg’s Pop-Tarts, as well as fast food restaurants (Spake, 2003). Many new products are created to capitalize on the nag factor. For instance, Baskin-Robbins used it to market innovative ice cream treats, including flavors such as Neverending Candy Crunch and Shrek Sundaes (covered in gummi worms), according to Schmuckler (2002). The nag factor also influences sales of refrigerated gelatin products – Kraft developed “X-treme Jell-O” to activate it through dialed-up tastes, flavors and colors (Thompson, 2001). Petrecca (2000) says that Bagel Bites, a Heinz Frozen Food Co. 7 frozen pizza-flavored snack, also take advantage of the nag factor, targeting teenage boys. Sales of Bagel Bites improved relative to competitors including Pillsbury's Totinos pizza rolls and Chef America Toaster Breaks following this change in targeting, and they are now the number two frozen appetizer/snack brand behind Totinos. Heinz pioneered invoking the nag factor through use of color. Ebenkamp (2002) notes that when Heinz introduced EZ Squirt Ketchup in late 2000, stores couldn't keep the bottles stocked, so the company followed up with colored Ore-Ida Fries, and Kraft Macaroni & Cheese also began to be offered in color. Color continues to be strategically useful to food marketers, in products ranging from margarine to Pepperidge Farm Goldfish Crackers. Thus, the nag factor is operational in many product categories: Atkin (1978) comments that it may be relevant for bread, hot dogs, potato chips, canned vegetables, frozen dinners, and peanut butter. Atkin was one of the early researchers in this area – he collected data in the breakfast cereal aisle of supermarkets, observing families with children that appeared to be between the ages of 3 and 12. The findings suggest that younger children are more likely to initiate a request, but older children have greater success upon doing so. Other researchers have also observed differences between younger and older children, although not all of the results are consistent. For instance, Heslop and Ryans (1980) find that older children, while interacting with their mothers after watching advertisements, are more likely to choose, request, and take home a particular cereal than are younger children. Upon obtaining choice responses from children ages 4-12, John and Laksmhi-Ratan (1992), observe that younger children are more likely than older children to switch to new beverage products. In summary, there appear to be age-related differences in impact of the nag factor. These differences may be due to developmental stage – Bahn (1986) says that the developmental break point occurs at age 7, 8 when children begin to understand the meaning of persuasive messages, separate perception from preference, and base their decisions on multiple dimensions of stimuli. Further, decisions of older children are more consistent than those of younger children. Sanft (1986) also considers the impact of advertising messages, finding that younger children pay greater attention and do more requesting of products, while older children have greater memory for commercial messages. Thus, considering the results of these studies, we might expect younger children to do more requesting, but older children to have greater success when they do so. In another study looking at the influence of persuasive messages, Goldberg, Gorn, and Gibson (1978) observe a relationship between advertising and children’s purchase influence attempts. They report that children who see advertising for healthy products are less likely to choose candy, sweetened snacks, Kool-Aid, and sugary cereal than those who see advertising for such products. Income may also impact the nag factor – according to Brandweek (1998), it is more effective among lower income groups. This may be due to a high proportion of single or divorced parents who tend to give in to kids' demands because of guilt. Finally, product preferences may, instead of being passed from child to parent, actually be transferred in the opposite direction. A study by Moore, Wilkie, and Lutz (2002) compares buying habits of mothers and their adult daughters, finding the highest levels of intergenerational influence regarding brand choice in the following categories: soup, catsup, facial tissue, peanut butter, and mayonnaise. Further, although daughters did not always purchase what their mothers did, they had very high levels of awareness of their mothers’ brand preferences. Although this study does not consider the choices of the daughters as children, the product preferences that carry over would very likely be those that were most salient when the daughters were young. 9 In conclusion, when we investigate the nag factor, we need to consider whether the product category is one in which children might have influence. We should take into account any relevant promotional activities at the time of the purchase, as persuasive messages may influence both the behavior of the child and the parent’s response. Also, the nature, frequency, and success of requests may differ depending on age, especially between children and teenagers. Further, family income has been found to influence response to the nag factor, with lower income families having a higher likelihood of purchase. Finally, we note that influence may travel in either direction between parent and child, and that it may not necessarily be considered a bad thing by either party. As John (1999, p.201) comments, “parents have become more accepting of children’s preferences.” Advertising Decisions and Public Policy Issues A number of researchers have called for public policy changes to reduce the impact of advertisers’ messages on preferences of children (see, for example, Borzekowski and Robinson 2001; Grier 2001; Smith and Stutts 1999). Legislators have also shown an interest; specifically, Senator Joe Lieberman requested new public policy addressing several issues, including (1) limiting the impact of advertising on children, (2) disclosing nutritional information in advertising of children’s products, (3) requiring foods sold in schools to be nutritional, and (4) requiring nutrition information to be supplied with fast food (Government Affairs 2003). Although impact of advertising on children has been demonstrated in many studies, they are typically cross-sectional and observe only short-term effects. Thus, several authors have called for longitudinal research that would measure effects over time to determine whether they are persistent (Borzekowski and Robinson 2001; Grier 2001; Kelly et al. 2002). It is important to identify how the undesirable impact comes about and what measures might mitigate it. 10 Researchers frequently note that children are influenced in product categories that might be considered bad for health reasons. For instance, Bolton (1983) observes long-run effects of media advertising on children that include an increase in eating snack foods and related calories, with a concomitant decrease in nutrition. However, her results also suggest that the influence of parents is stronger than that of advertising. Thus, she recommends public policy that works to increase parents’ nutritional well-being and understanding, in order to improve children’s diets. Borzekowski and Robinson (2001) find that for younger children (2-6 years of age), brief exposures to food advertising influence preferences in categories including juice, doughnuts, bread, peanut butter, breakfast cereal, snack cake, candy, and fast food chicken. The authors suggest that epidemic-level child obesity makes it necessary to address the situation with appropriate public policy. Grier (2001) finds that marketers systematically target children who are younger than the rated age ranges for movies, electronic games, and music – she concludes that companies need to balance profit motives with good corporate citizenship. Cigarette makers intentionally target underage children, with advertising that is thought to lead to both product category and brand-level demand (Smith and Stutts 1999), but other influences including prior beliefs, family, and peers are found to carry greater impact. Thus, the authors recommend that nonsmoking activities be directed at parents and siblings, due to their high level of influence on smokers. (They also note that antismoking messages need to be more relevant, for instance, focusing on beauty concerns.) Kelly et al. (2002) show that, among 12-16 year olds, brand attitude is a mediator between attitude toward an advertisement and attitude toward a product category. Thus, while marketers work to influence brand attitudes, they might also influence social desirability of a 11 product category, which is the level at which public policy makers have the greatest interest. Image advertising is found to produce more socially desirable assessments than text-only advertising; thus, more heavily advertised brands utilizing image advertising may define a product category for consumers. This describes the mechanism by which promotional activities might influence desirability of a product category; in the present study, we consider whether public policy changes may be needed to reduce the impact of advertising on children. Testable Ideas from Prior Research Summarizing our review of the literature, there are several ideas that we examine in the present research. First, can we observe differences in purchase behavior between product categories that are primarily for adults, as compared to those directed at children? A related question is whether the presence or absence of children in a household may be associated with buying patterns. This would be necessary in order for the nag factor to be effective. Brand-level promotional spending may be used in several different ways, including temporary price cuts, feature advertisements, in-store displays, and media advertising – we identify differences in the usefulness of each of these alternatives. In addition, we consider the role of variety seeking behavior, and assess this alternative explanation for dynamic purchases over time. Finally, we address the question of how public policy should view advertising directed at children, offering advice to policy makers from a marketing point of view. MODEL DEVELOPMENT AND ESTIMATION The objective of our study is to empirically test for the dual influences of product category (whether it is aimed at children or adults) and presence or absence of children in the household on response to various promotional activities. It is important to use longitudinal data, 12 to see if the influence of promotions reaching children will last over a period of time. Further, we need to distinguish purchase-level effects capturing longitudinal heterogeneity from household-level effects due to cross-sectional heterogeneity. We test our ideas within a modeling framework that segments at the household and purchase levels simultaneously (to account for both effects). We begin by describing the theoretical model, and follow it with specification of the empirical model and discussion of our estimation approach. Model Description Consistent with the extant modeling literature, we assume that the utility of brand b for household h in period t can be written as: U hbt = X hbt β bh + ε hbt (1) where Xhbt is a vector of predictor variables relevant to brand b and household h in period t, the β bh are household-specific response parameters, and εhbt is an error term. We assume that the error term is extreme-value distributed, which results in a multinomial logit model, and the probability that brand b is chosen by household h in period t is therefore: B ⎛ ⎞ Pbth = exp(U hbt ) / ⎜1 + ∑ exp(U hit ) ⎟ ⎝ i =1 ⎠ (2) where B is the number of alternatives. The number “1” in the denominator represents an “outside good” in the category; it is used in this research to accommodate household h’s purchases of brands other than the focal brands. Given our research questions – how does the presence of children in a household affect response to promotional activities and affect a household’s variety seeking behavior? – we define the vector of predictor variables, Xhbt to include (1) regular (non-promoted) price, rbt, of brand b in period t, (2) deal amount, abt, of brand b in period t, (3) a dummy variable, mbt, 13 indicating whether or not brand b had a feature advertisement in period t, (4) a dummy variable, dbt, indicating whether or not brand b was displayed in period t, and (5) two state-dependence terms including sbht, which captures whether or not household h purchased brand b on the last shopping trip, and ehbt, the amount of time (in days) between the purchase in period t and period t-1. The state dependence variables allow us to represent a household’s variety seeking behavior and how it may change as the time between purchases increases. Thus, the utility in equation (1) can be written as: U hbt = β obh + β 1h rbt + β 2h a bt + β 3h mbt + β 4h d bt + β 5h s hbt + β 6h s hbt e hbt + ε hbt (3) Price is separated into regular and deal prices, as consumers respond differently to each (see, e.g., Blattberg, Briesch, and Fox 1995; Briesch, Chintagunta, and Matzkin 2002). Separating price effects also allows us to test whether the presence of children in a household changes the household’s response to price and non-price promotions (in-store displays and feature advertising). We include time between purchases in our model because it permits us to assess whether increased time is associated with increased variety seeking. Specifically, if β6 < 0, then households are increasingly variety seeking as time passes, and if β6 > 0, then households are increasingly brand loyal as time passes. It is reasonable to assume that as the time between purchases increases, households (especially those with children) are more likely to have seen advertisements for products in the category in the interim. Therefore, this term can be viewed as an indirect test of the influence of advertising and other word of mouth effects on household purchases. 14 To test whether the presence of children in a household has a differential effect on the household’s marketing mix response and variety seeking behavior, we allow the response coefficients in equation (3) to be a function of the household’s demographics, as follows: β ih = γ 0i + γ 1i k h + γ 2i f h + γ 3i ih + ζ ih , for i =1..6 (4) where kh is a binary variable that is set to one if children are present in the household, fh is the number of people in household h, ih is the income of household h, and ζ ih is a random term that is assumed to have a normal distribution. The brand intercept terms, β obh , b=1...B, are assumed to have independent normal distributions. This formulation allows us to test for the effect of children in the household (i.e., parameter γ1i), controlling for the size and income of the household, which eliminates alternative explanations for our results. For instance, one alternative explanation for finding that households with children engage in more variety seeking behavior is that households with more people exhibit illusory variety seeking behavior because the household purchases items for multiple individuals. Similarly, an alternative explanation for finding that households with children are more price sensitive is that such households have lower income and related budget constraints. Based on our review and analysis of the relevant literature, we propose to test for the effects summarized in Table 1. 15 Table 1: Potential Household-Level Effects Tested Empirically Effect Children’s Product Categories Tests Nag factor: Variety seeking behavior. Households with children are more likely to engage in variety seeking, because children observe advertising and “try out” new preferences. γ15 < 0 for children’s categories, zero for adult categories. Price sensitivity Due to variety seeking and costs of living of households with children, they are more price sensitive. γ11 < 0 for children’s product categories, not significant for adult product categories. Price promotions Children are typically unaware of price promotions, so no difference is expected between households with and without children. γ12 not significant for all categories. Feature advertising Children are typically unaware of feature advertising, so no difference γ13 not significant for all categories. is expected between households with and without children. In-store displays Children influence in-store decisions; one reason for displays is to raise the salience of the brand and category. Thus, households with children are expected to respond more strongly to displays than those without. Time between purchases and state dependence γ14 > 0 for children’s product categories, not significant for adult product categories. Media advertising for children’s γ16 < 0 for children’s categories categories focuses on new characters whose advertising focuses on and features instead of focusing on new characters and features, image and building brand loyalty. not significant for adult categories and children’s categories whose advertising focuses on brand image. Model Estimation We use Simulated Maximum Likelihood (Allenby and Rossi 1999; Hajivassilios and Rudd 1994) to integrate the random terms in the parameter vectors. Because a large number of random draws would be required to accurately integrate the random terms, we use 150 draws from a quasi-random Halton Sequence (Train 1999; Bhatt 2001). Bhatt argues that 100 draws 16 from a Halton sequence is roughly equivalent to 1000 to 1500 draws from a random normal distribution, so this should be sufficient. Data Description Our data set is a multi-store panel from Denver covering a 118 week period starting in the mid-1990s. We selected three product categories for analysis: breakfast cereal, carbonated beverages (soda) and coffee. Cereal and soda were selected because they are clearly important to children (Dolliver 1998; Embrey 2004; John 1999; Rose et al. 2002; Spake 2003) and they are also the two categories in which teenagers have the greatest impact on purchase decisions (Promar International 2001). We divided the cereal category into two groups: those brands targeted to children (we termed this group Kids’ Cereal) and those brands aimed at adults (Adult Cereal), based on work previously done by Briesch (1995) and Cotterill and Haller (1997). Splitting cereal into sub-categories provides a strong test of the theory, as any differences in results cannot be attributed to idiosyncratic differences between categories. Following the split, we have one cereal and one beverage category where children are expected to influence purchase decisions (Kids’ Cereal and Soda), and one cereal and one beverage category where children are not expected to influence purchase decisions (Adult Cereal and Coffee). Descriptive statistics for these categories are provided in Table 2. Brands within each category were included as focal brands if they had at least three percent market share. We used this cutoff to ensure that the number of brands was manageable while still including a substantial portion of the category purchase activity. As shown in Table 2, focal brands accounted for at least 75% of category purchases for all categories. The raw share numbers represent the brand shares before any observations are excluded. 17 After the brands were selected, families were included in the data set if they made at least three purchases in the category over the 118 weeks and if at least 80 percent of their purchases were the focal brands. We use the 80% cutoff to ensure that we are modeling purchase activity of the focal brands. Note that all purchases made by the selected families are included in the data set and variable constructions – non-focal brands are included as “other.” Finally, each observation of each family was randomly assigned to either the estimation sample or the hold-out sample, having a fifty percent probability for either. (Note that the first observation of each family is not included in either the estimation or holdout sample, as it is required to initialize the state dependence variables.) Looking at the descriptive information in Table 2, the demographic compositions of the households selected for each category are all very similar in terms of income and family size. Based on the total number of households included in the data set, the number of families with children is roughly 44% of the total for both Adult Cereal and Kids’ Cereal. The number of households with children is about 38% of the total for both the Soda and Coffee beverage categories. It is interesting to note that while Kids’ Cereal is targeted towards children, the majority of households making purchases in this category do not have any children – however, the majority of purchases made in this category are made by households with children. 18 Table 2: Category Descriptive Statistics Number of families % Families with children Average Family size/10 Average Income/ 100,000 Avg. Interpurchase time (weeks) % of purchases made by families with children Brand 1: Share Brand 2: Share Brand 3: Share Brand 4: Share Brand 5: Share Brand 6: Share Brand 7: Share Brand 8: Share Brand 9: Share Brand 10: Share Brand 11: Share Brand 12: Share Adult Cereal Coffee Kids’ Cereal Soda 770 44.2% 937 38.0% 721 44.4% 954 37.6% 0.29 (0.15) 0.17 (0.05) 10.17 (12.45) 0.28 (0.14) 0.17 (0.05) 10.37 (12.26) 0.28 (0.14) 0.17 (0.05) 8.26 (10.43) 0.26 (0.14) 0.17 (0.05) 4.33 (6.79) 40.7% 34.3% 59.8% 43.9% Ctl Bran: 3.62 GM Oatmeal: 4.70 GM Total: 6.46 K All Bran: 8.36 K Miniwheats: 11.88 K Raisin Bran: 6.17 K Special K: 3.05 N Wheat Squares: 14.11 P Fruit/Fiber: 3.51 P Grape Nuts: 8.83 P Raisin Bran: 5.29 Other: 24.02 Boyer Brothers: 15.49 Control Brand: 12.83 Folgers: 27.34 High Yield: 5.47 Hills Bros: 6.00 MJB: 9.70 Master Blend: 3.97 Maxwell House: 8.50 Other: 10.76 Ctl Flavored Oats : 3.36 Ctl Other: 3.67 GM Corn Pops: 3.26 GM Flav. Cheerios: 8.32 GM Kix: 7.16 GM Lucky Charms: 4.24 K Frosted Flakes: 6.24 K Fruit Loops: 3.24 MOM Flav oats: 6.18 P Flav oats: 4.04 P Honey-Comb: 3.18 P Pebbles: 4.19 Q Cap’n Crunch: 9.29 Q Life: 4.80 Q Toasted Oats: 3.82 Other: 24.83 7 Up: 5.07 AW Root Beer: 3.30 Canada Dry: 3.70 Coke: 16.62 Control Brand: 14.82 Dr Pepper: 6.36 Mountain Dew: 5.55 Pepsi: 23.30 Sprite: 3.67 Other: 17.61 Brand 13: Share Brand 14: Share Brand 15: Share Brand 16: Share NOTE: for cereal, Ctl=Control Brand, GM=General Mills, K=Kellogg’s, MOM=Malt-O-Meal, N=Nabisco, P=Post, Q=Quaker. 19 Results Table 3 provides both the estimation and holdout sample results for the four categories. In addition to the hierarchical model described above, we estimated a model without any hierarchical equation terms (i.e., in equation (4), β ih = γ 0i , ∀h = 1..H , i = 1..6 and in equation (3), β 0h = β 0 , ∀h = 1..H ) for comparison. This model is called “Fixed” in the table, while the hierarchical model is denoted by “Hier’l.” Table 3: Model Estimation Results Adult Cereal Fixed Estimation Sample 11483 -Log Likelihood 6147 Choices 770 Families 17 Parameters 23000 AIC 23115 Swartz (BIC) 2241 Likelihood Ratio (LR) <0.0001 LR Probability Coffee Hier’l Fixed Kids’ Cereal Hier’l Fixed Soda Hier’l Fixed Hier’l 10363 10354 9374 13182 12102 30401 26896 6147 7418 7418 6183 6183 17766 17766 770 937 937 721 721 954 954 52 14 46 21 60 14 48 20830 20736 18839 26406 24324 60829 53887 21179 20832 19157 26547 24728 60938 54261 1961 2160 7010 <0.0001 <0.0001 <0.0001 Holdout Sample -Log Likelihood Choices Families 12112 10981 10930 9853 13734 12704 30739 27367 6401 6401 7685 7685 6388 6388 18051 18051 769 769 936 936 718 718 962 962 In terms of model selection, all of the model selection criteria (Swartz Information Criteria or BIC, AIC, and likelihood ratio (LR) test) indicate that the hierarchical model fits 20 significantly better than the fixed model in all categories. In addition, performance in the holdout sample is better for the hierarchical than the fixed model. Parameter Estimates Tables 4 through 9, included in this section, provide hierarchical model (4) parameter estimates for state dependence and each of the marketing mix variables. (The full set of parameter estimates is available from the authors upon request.) We use these results to address our research questions – specifically, do promotional activities differentially influence households with children and those without, and if so, how is purchasing behavior affected? Table 4: Coefficient Estimates for State Dependence Category Adult Cereal Coffee Kids’ Cereal Soda Intercept (γ0) 0.813 (0.248) 1.640 (0.260) 1.162 (0.225) 0.543 (0.115) Kids (γ1) 0.125 (0.196) 0.202 (0.197) -0.246 (0.146) -0.236 (0.082) Income (γ2) -1.885 (1.290) -0.003 (1.281) 1.658 (1.055) 0.034 (0.594) Family Size (γ3) 0.040 (0.062) -0.086 (0.072) -0.104 (0.047) 0.050 (0.028) Error (ζ) 1.877 (0.109) 1.829 (0.113) 1.090 (0.102) 0.552 (0.073) Note: Values printed in boldface are significant at the p<0.05 level. Because the intercept for state dependence is positive and significant in all four product categories, we find that households are inertial in their brand purchasing behavior; in other words, they tend to repurchase the same brands rather than engage in variety seeking. However, we note that the error term is also significant, which implies there is heterogeneity in the amount of inertia present among households. Thus, certain households are more inertial than others, and variety seeking behavior occurs in all four product categories. Our results suggest that the nag factor exists in product categories targeted at children, and that its impact can be measured. The term indicating the effects of children present in the household (γ1) is negative and significant for both product categories targeted at children, and 21 insignificant for adult products. Thus, we find evidence that advertising aimed at children influences household buying behavior, leading to increases in variety seeking, in particular. The variable representing family size (γ3) is significant only for the two product categories targeted at children, and even so, the direction of the effect differs for Soda and Kids’ Cereal. The result for cereal is in the expected direction, and implies that, as the number of children in the household increases, the degree of illusory variety seeking increases. Thus, this result is consistent with the suggestion that parents switch brands to accommodate changing preferences among their children. On the other hand, the coefficient for Soda indicates that households do not purchase a greater variety of products for a larger number of people. It is possible this outcome is related to the nature of advertising for the product category. Soft drink marketers often try to build brand loyalty through image advertising (Kelly et al., 2002); this may at least partially explain the lack of increase in variety seeking behavior with household size. Another possible explanation is refrigerator space. Large families may be able to purchase a variety of cereals to accommodate different preferences, but limited refrigerator space may force them to get by with a more limited selection of soft drinks. This result suggests a need for future research to better understand the underlying cause. Table 5 provides parameter estimates for the interaction of state dependence and time since the last purchase. Thus, these results indicate any change in inertia that might be associated with the amount of time that has elapsed since the previous purchase in the product category. For our two adult product categories, most of the results are not significant. However, we note that the error term is significant for the adult categories and not for the children’s categories, which implies that heterogeneity exists, but only for product categories targeted to adults. For the children’s product categories, the intercept is positive; it is 22 significant (p<0.05) for Soda and approaches significance (p<0.10) for Kids’ Cereal. This suggests that households buying more frequently tend to engage in more variety seeking, which is consistent with an increase in the impact of media advertising. Table 5: Coefficient Estimates for State Dependence and Time since Last Purchase Category Adult Cereal Coffee Kids’ Cereal Soda Intercept (γ0) 0.171 (0.475) -0.045 (0.337) 0.713 (0.411) 0.722 (0.278) Kids (γ 1) Income (γ2) 0.093 7.223 (0.402) (2.575) -0.035 0.275 (0.272) (1.706) -0.580 -0.666 (0.319) (2.337) -0.029 0.555 (0.207) (1.470) Family Size (γ3) -0.169 (0.139) -0.055 (0.098) 0.096 (0.115) -0.105 (0.067) Error (ζ) 0.836 (0.300) 1.069 (0.171) -0.066 (0.215) 0.163 (0.356) Note: Boldface values are significant at the p<0.05 level; Italicized items are significant for p<0.10. Also in Table 5, we note the negative and significant coefficient for presence of children in the household for the Kids’ Cereal category. This result must be interpreted in light of the value obtained for the intercept term. For this product category, the presence of children in a household appears to cancel the effect of the positive intercept term, which would otherwise indicate inertial behavior. Thus, the amount of variety seeking behavior that occurs in the Kids’ Cereal category does not tend to change with the time between purchases for households with children, but it declines with the time between purchases for households without children. On the other hand, for the Soda category, households both with and without children see a decrease in variety seeking as time between purchases increases. The increasing inertia in the Soda category may be due to the nature of advertising for soft drinks, which typically focuses on brand image and reinforces loyalty, as compared to advertising for children’s breakfast cereals, which offers a dynamic parade of new characters and tie-ins, encouraging new product trial and variety seeking behavior (Dalmeny 2003; Kelly et al. 2002). 23 The coefficient estimates for regular price are detailed in Table 6. Face validity is provided by the fact that all of the intercepts are negative and significant (p<0.01). The coefficient for the presence of children in the household is negative in both product categories targeting children, indicating that price sensitivity for such products is greater in households with children. Further, this coefficient is insignificant for Coffee and marginally significant (p<0.10) for Adult Cereal. Therefore, we find limited support for our proposition that, although variety seeking may be induced by targeting children, price sensitivity also increases in households with children. These results are consistent with those of Kahn and Raju (1991), who find that variety seeking individuals are also more price sensitive. This may reflect a general need of families with children to find ways of cutting food costs. Table 6: Coefficient Estimates for Regular Price Category Adult Cereal Coffee Kids’ Cereal Soda Intercept (γ0) -9.228 (1.336) -7.679 (0.872) -5.220 (1.159) -12.140 (5.947) Kids (γ1) -1.368 (0.747) 0.692 (0.601) -1.987 (0.601) -8.900 (3.752) Income (γ2) 1.851 (4.831) 19.069 (4.034) 3.654 (4.181) -3.584 (27.872) Family Size (γ3) 0.186 (0.259) -0.242 (0.222) 0.251 (0.178) -0.665 (1.285) Error (ζ) 0.976 (0.758) 2.982 (0.333) -1.252 (0.390) 9.481 (2.611) Note: Boldface values are significant at the p<0.05 level; Italicized items are significant for p<0.10. Coefficient estimates for deal amount are given in Table 7. They offer face validity, in that all of the intercepts are positive and three of the four are significant (p<0.01), with the fourth being marginally significant (p<0.10). We find support for our proposition that the presence of children in a household does not either increase or decrease household response to temporary price cuts offered in children’s product categories. However, we do observe a significant positive coefficient in the Coffee category, suggesting that families with children do respond to price promotions for coffee. 24 Table 7: Coefficient Estimates for Price Promotion Deal Amount Category Adult Cereal Coffee Kids’ Cereal Soda Intercept (γ0) 14.884 (3.069) 7.901 (1.561) 19.718 (2.633) 23.696 (12.848) Kids (γ1) 1.615 (2.573) 2.329 (1.207) -0.580 (1.765) 11.006 (8.882) Income (γ2) 0.413 (15.675) 1.373 (8.098) -12.616 (12.633) 4.089 (63.809) Family Size (γ3) 0.240 (0.893) -0.233 (0.437) -1.122 (0.563) 7.500 (31.683) Error (ζ) -1.186 (1.835) -3.305 (1.029) -1.738 (1.723) 6.918 (7.529) Note: Boldface values are significant at the p<0.05 level; Italicized items are significant for p<0.10. Table 8 provides coefficient estimates for in-store displays. The results offer face validity, because in all categories, either the intercept is positive and significant, or the error term is significant, indicating heterogeneity that implies some or all households respond to display activity. However, we do not find support for our proposition that households with children are more sensitive than those without to in-store displays of brands in product categories targeted toward children. One possible explanation for this is that children respond to shelf placement rather than to displays – products placed on lower shelves where children can see them might be more attractive to children than those on end-aisle displays (Issue Brief 2004). However, we do note a positive and significant response to in-store displays of Soda, and a positive response nearing significance for Kids’ Cereal. Table 8: Coefficient Estimates for In-Store Displays Category Adult Cereal Coffee Kids’ Cereal Soda Intercept (γ0) 0.053 (0.352) 0.443 (0.501) 0.561 (0.317) 0.705 (0.129) Kids (γ1) 0.434 (0.265) -0.587 (0.357) -0.203 (0.213) -0.086 (0.091) Income (γ2) 2.740 (1.703) -1.884 (2.499) -0.904 (1.531) 0.857 (0.680) Family Size (γ3) -0.048 (0.093) 0.431 (0.133) 0.056 (0.068) -0.052 (0.032) Error (ζ) 0.589 (0.160) -1.666 (0.309) 0.640 (0.128) 0.064 (0.106) Note: Boldface values are significant at the p<0.05 level; Italicized items are significant for p<0.10. 25 Finally, Table 9 provides coefficient estimates for feature advertising. The intercept for all product categories is positive and significant, offering face validity. Further, our proposition that households with children respond no differently to features than those without is supported by the results. Table 9: Coefficient Estimates for Feature Advertisements Category Adult Cereal Coffee Kids’ Cereal Soda Intercept (γ0) 1.070 (0.318) 1.293 (0.485) 0.713 (0.311) 0.479 (0.130) Kids (γ1) -0.071 (0.254) 0.368 (0.379) 0.170 (0.208) -0.030 (0.091) Income (γ2) -3.672 (1.654) 2.907 (2.459) -0.200 (1.497) -1.190 (0.690) Family Size (γ3) 0.137 (0.086) -0.273 (0.135) 0.004 (0.067) 0.034 (0.031) Error (ζ) -0.590 (0.165) 0.240 (0.253) 0.201 (0.212) -0.016 (0.062) Note: Boldface values are significant at the p<0.05 level; Italicized items are significant for p<0.10. Empirical Tests of Ideas from the Literature We can now relate the detailed findings back to the testable effects described in Table 1. • Nag factor: consistent with our proposition, households with children engage in more variety seeking than households without children for both the Soda and Kids’ Cereal product categories. Further, this effect is not observed for either Adult Cereal or Coffee. • Price sensitivity: consistent with our proposition, for both children’s product categories, households with children are more sensitive to regular price than households without children. This effect is not found for the adult categories. • Price promotions: we find limited support for our proposition that households with children are not differentially affected by price promotions. Specifically, for three of the four product categories (Kids’ Cereal, Soda and Adult Cereal), we do not observe a significant difference between households with and without children in terms of their response to temporary price cuts. • Feature advertising: our proposition that there is no difference in response to feature advertisements between households with and without children is fully supported by results for all four product categories. • In-store display: the proposition that presence of children in a household is associated with increased response to in-store displays of children’s products was not supported. This result suggests that, while households with children do more variety seeking than those without, this behavior is not driven by display activity. It may instead be related to retailers’ shelf placement (e.g., children’s cereals are often placed on lower shelves where they are more easily viewed by children in the cereal aisle). 26 • Time between purchases: our findings support the proposition that variety seeking behavior increases with time, where children are present and product category advertising focuses on dynamic characters and tie-ins (Kids’ Cereal). Further, this increase in variety seeking does not occur in adult product categories or categories in which the marketing mix focuses on enhancing brand image and loyalty (Soda). • State dependence: for all four product categories, consumers are inertial in their brand purchasing behavior. Further, only in the Adult Cereal category do we find that time between purchases reinforces increasingly brand loyal behavior. CONCLUSIONS Discussion of Managerial and Public Policy Implications We set out to improve understanding of marketing mix strategy and design factors, especially for product categories that appeal primarily to children and teenagers. Marketers often rely on the nag factor, through which children communicate to their parents which brands they wish to buy. Although retailers may believe that in-store displays encourage children to request displayed products, our results indicate this is not particularly effective. Our findings also support our propositions that promotional price cuts and feature advertisements are not relevant to children. However, children do appear to influence purchase of child oriented products for which they have had greater opportunity to observe media advertising. Thus, as marketers, we believe that media advertising may be the most effective use of promotional dollars for brands in product categories targeted to children. Given this, what should be our response to the public policy debate over advertising directed at children? First, consider the product categories we studied: both Soda and Kids’ Cereal may not be considered “good for you,” but they also are not inappropriate products which the law would prohibit selling to children. Much of the public policy literature deals with exposure of children to advertising for adult products such as cigarettes, alcohol, and 27 entertainment items rated for adult usage. By comparison, advertising for food products that may contribute to child obesity seems tame and certainly falls into a gray area. Prior research (Kelly et al. 2002) indicates that advertising for a brand tends to increase desire for the product category. Using this result along with our findings, we can say that advertising children’s food category brands to children is likely to increase their desire for the product category. Thus, the product category would appear to be the most effective level for any public policy intervention. Our results indicate that households with children tend to do more variety seeking when buying children’s products than do households without children. This result is connected to time between purchases for Kids’ Cereal, which suggests that as children view more advertising focusing on the latest character or tie-in, they exert greater purchase influence for the brand advertised. This switching between brands to follow the latest fad implies that the advertising is most effective for the next purchase in the product category. Thus, consistent with our statement above, the public policy question must address advertising for an entire product category if it is to decrease children’s requests for brands. Further, our results indicate that reducing advertising intensity will not be sufficient – brand switching induced by advertising will continue to occur. Even if advertising were eliminated completely, this would not guarantee any decrease in child obesity. Perhaps a more effective means of introducing public policy to control purchases of children’s food products would be to consider a sales tax on brands in these categories. Our results indicate that, for children’s product categories, households with children are more sensitive to regular price than households without children. Thus, a sales tax on such product categories would impact sales of products aimed at children to families with children. This would appear to be a much more direct route to reducing purchases of foods that are not 28 healthful among households with children than attempting to reduce children’s desire for such brands. Further, tax dollars collected could be used to pay for such activities as interventions to reduce time children spend with the media and public educational campaigns promoting healthy eating habits. Limitations and Directions for Future Research Although most of our results provide a consistent picture of the marketplace for children’s and adult food products, there are two findings that warrant further research to improve understanding. First, our observation that households with children do more variety seeking than those without is not fully explained by our research results – it is unclear whether retailers might be able to influence this behavior. We do find that variety seeking is not driven by in-store displays, and suggest that it may instead be related to retailers’ shelf placement. However, we do not have data as to shelf placement and thus, are not able to test this idea in the present study. (We would also like to examine why in-store displays do not affect the tendency of households with children to purchase.) Second, we note that, in the Soda category, there is an increase in inertia with household size. Thus, larger households are more likely to repurchase the same brand than are smaller households. This may be related to purchases of a larger package size for larger families (e.g. two-liter bottle), but we are unable to test this idea in the present research, and must leave it for a future study. Another limitation of the present work is that the data were drawn from a single time period and a single region. Thus, future research should validate these findings using other times, cities, and product categories. We would also like to integrate media advertising into the model to directly test its impact on brand choice. Other ideas for further study include obtaining a breakdown of the data for households with children to examine the impact on choice 29 of children’s age range, to test ideas from prior research that suggest there are differences by developmental stage. Another possibility to consider is the nature of the appeal that is used in media advertising. We observe differences in choice behavior that we believe are due to the nature of the advertising strategy, i.e. whether it is image-oriented and intended to build brand loyalty, or more focused on introducing exciting new characters and tie-ins, and believe this warrants further investigation. 30 References Allenby, Greg M., and Peter E. Rossi (1999), “Marketing Models of Consumer Heterogeneity,” Journal of Econometrics 89(1-2), 57-78. Atkin, Charles K. (1978), “Observation of Parent-Child Interaction in Supermarket DecisionMaking,” Journal of Marketing 42(4), 41-45. Bahn, Kenneth D. (1986), “How and When Do Brand Perceptions and Preferences First Form? A Cognitive Developmental Investigation,” Journal of Consumer Research, 13(3), 382393. Bhatt, Chandra (2001), “Simulation Estimation of Mixed Discrete Choice Models Using Randomized and Scrambled Halton Sequences,” Working paper, University of Texas at Austin. Blattberg, Robert C., Richard Briesch, and Edward J. Fox (1995), “How Promotions Work,” Marketing Science 14(3), 122-132. Bolton, Ruth N. (1983), “Modeling the Impact of Television Food Advertising on Children’s Diets,” Current Issues and Research in Advertising 6(1), 173-199. Borzekowski, Dina L.G., and Thomas N. Robinson (2001), “The 30-Second Effect: An Experiment Revealing the Impact of Television Commercials on Food Preferences of Preschoolers,” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 101(1), 42-46. Boulding, William, Eunkyu Lee, and Richard Staelin (1994), “Mastering the Mix: Do Advertising, Promotion, and Sales Force Activities Lead to Differentiation?,” Journal of Marketing Research 31(2), 159-72. Brandweek (1998), “From Nag to the Bag,” 39(15), 25. Briesch, Richard A. (1995), “Optimal Retailer Strategies Incorporating Manufacturer Trade Deals, Consumer Expectations, and Consumer Inventory Levels,” Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Northwestern University. Briesch, Richard A., Pradeep K. Chintagunta, and Rosa Matzkin (2002), “Semiparametric Estimation of Brand Choice Behavior,” Journal of American Statistical Association 97(460), 973-982. Bucklin, Randolph E., and Sunil Gupta (1992), “Brand Choice, Purchase Incidence and Segmentation: An Integrated Modeling Approach,” Journal of Marketing Research 29(2) 201-15. Cotterill, Ronald W., and Lawrence E. Haller, (1997), “An Econometric Analysis of the Demand for RTE Cereal: Product Market Definition and Unilateral Market Power Effects,” Report 35, Food Marketing Policy Center, University of Connecticut. Dalmeny, Kath (2003), “Food Marketing: The Role of Advertising in Child Health,” Consumer Policy Review 13(1), 2-7. Dolliver, Mark (1998), “How Kids Make the ‘Nag Factor’ an Economic Force,” Adweek 39(12), 18. Ebenkamp, Becky (2002), “The Color of Munchies,” Brandweek 43(13), 22-24. 31 Embrey, Alison (2004), “Great Minds Think Alike,” Display and Design Ideas 16(3), 114-115. Fader, Peter S., and Leonard M. Lodish (1990), “A Cross-Category Analysis of Category Structure and Promotional Activity for Grocery Products,” Journal of Marketing 54(4), 52-65. Fader, Peter S., and Leigh McAlister (1990), “An Elimination by Aspects Model of Consumer Response to Promotion Calibrated on UPC Scanner Data,” Journal of Marketing Research 27(3), 322-332. Foley, Michael (2002), Personal Communication as H.J. Heinz Company, L.P. Trade Funding Analyst. Goldberg, Marvin E., Gerald J. Gorn, and Wendy Gibson (1978), “TV Messages for Snack and Breakfast Foods: Do They Influence Children’s Preferences?,” Journal of Consumer Research 5, 73-81. Government Affairs (2003), “The Valuing Families Agenda: Empowering Our Parents and Protecting Our Children,” Washington, D.C.: American Advertising Federation, (http://www.aaf.org/government/legislative_20031204.html). Grier, Sonya A. (2001), “The Federal Trade Commission’s Report of the Marketing of Violent Entertainment to Youths: Developing Policy-Tuned Research,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 20(1), 123-132. Grover, Rajiv, and V. Srinivasan (1992), “Evaluating the Multiple Effects of Retail Promotions on Brand Loyal and Brand Switching Segments,” Journal of Marketing Research 29(1), 76-89. Guadagni, Peter M., and John D.C. Little (1983), “A Logit Model of Brand Choice Calibrated on Scanner Data,” Marketing Science 2(3), 203-38. Gupta, Sachin, and Pradeep K. Chintagunta, (1994), “On Using Demographic Variables to Determine Segment Membership in Logit Mixture Models,” Journal of Marketing Research 31(1), 128-36. Hajivassilios, V.A., and P.A. Rudd (1994), “Classical Estimation Methods for LDV Models Using Simulation,” Handbook of Econometrics, R.F. Engle and D.L. McFadden, eds., NH: Elsevier, 2384-2441. Heilman, Carrie M., Douglas Bowman, and Gordon P. Wright (2000), “The Evolution of Brand Preferences and Choice Behaviors of Consumers New to a Market,” Journal of Marketing Research 37(2), 139-155. Heslop, Louise A., and Adrian B. Ryans (1980), “A Second Look at Children and the Advertising of Premiums,” Journal of Consumer Research 6(4), 414-420. Inman, J. Jeffrey, Leigh McAlister (1993), “A Retailer Promotion Policy Model Considering Promotion Sensitivity,” Marketing Science 12(4), 339-56. Issue Brief (2004), “The Role of Media in Childhood Obesity,” Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Publication #7030 (www.kff.org). John, Deborah Roedder (1999), “Consumer Socialization of Children: A Retrospective Look at Twenty-Five Years of Research,” Journal of Consumer Research 26(3), 183-213. 32 John, Deborah Roedder, and Ramnath Lakshmi-Ratan (1992), “Age Differences in Children’s Choice Behavior: The Impact of Available Alternatives,” Journal of Marketing Research 29(2), 216-226. Kahn, Barbara E., and Jagmohan S. Raju (1991), “Effects of Price Promotions on VarietySeeking and Reinforcement Behavior,” Marketing Science 10(4), 316-337. Kamakura, Wagner A., and Gary J. Russell (1989), “A Probabilistic Choice Model for Market Segmentation and Elasticity Structure,” Journal of Marketing Research 26(4), 379-90. Kelly, Kathleen J., Michael D. Slater, and David Karan (2002), “Image Advertisements’ Influence on Adolescents’ Perceptions of the Desirability of Beer and Cigarettes,” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 21(2), 295-304. Krishnamurthi, Lakshman, and S. P. Raj (1991), “An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between Brand Loyalty and Consumer Price Elasticity,” Marketing Science 10(2), 17283. McAlister, Leigh, and Edgar Pessemier (1982), “Variety Seeking Behavior – An Interdisciplinary Review,” Journal of Consumer Research 9(3), 311-322. Mela, Carl F., Sunil Gupta, and Donald R. Lehmann (1997), “The Long-Term Impact of Promotion and Advertising on Consumer Brand Choice,” Journal of Marketing Research 34(2), 248-261. Moore, Elizabeth S., William L. Wilkie, and Richard J. Lutz (2002), “Passing the Torch: Intergenerational Influences as a Source of Brand Equity,” Journal of Marketing 66(2), 17-37. Narasimhan, Chakravarthi, Scott A. Neslin, and Subrata K. Sen (1996), “Promotional Elasticities and Category Characteristics,” Journal of Marketing 60(2), 17-30. Neslin, Scott A. (2002), Sales Promotion. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute. Papatla, Purushottam, and Lakshman Krishnamurthi (1996), “Measuring the Dynamic Effects of Promotions on Brand Choice,” Journal of Marketing Research 33(2), 20-35. Petrecca, Laura (2000), “Bagel Bites Finds Tween Target as X Games Sponsor,” Advertising Age 71(35), 59-63. Promar International (2001), “Generation Y: Winning Snack Strategies,” The Strategic Consultant Series. Rose, Gregory M., David Boush, and Aviv Shoham (2002), “Family Communication and Children’s Purchasing Influence: A Cross-National Examination,” Journal of Business Research 55, 867– 873. Ryans, Adrian B. (1980), “A Second Look at Children and the Advertising of Premiums,” Journal of Consumer Research 6(4), 414-420. Sanft, Henrianne (1986), “The Role of Knowledge in the Effects of Television Advertising on Children,” Advances in Consumer Research, 13(1), 147-152. Schmuckler, Eric (2002), “Media Plan of the Year,” Adweek Midwest Edition 43(25), SR1-23. 33 Seetharaman, P. B., Andrew Ainslie, and Pradeep K. Chintagunta (1999), “Investigating Household State Dependence Effects Across Categories,” Journal of Marketing Research 36(4), 488-500. Smith, Karen H., and Mary Ann Stutts (1999), “Factors that Influence Adolescents to Smoke,” Journal of Consumer Affairs 33(2), 321-357. Spake, Amanda (2003), “Hey, Kids! We've Got Sugar and Toys,” U.S. News & World Report 135(17), 62-63. Thompson, Stephanie (2001), “Jell-O taken to 'X-tremes',” Advertising Age 72(47), 4-12. Train, Kenneth (1999), “Halton Sequences for Mixed Logit,” Working Paper, Department of Economics, University of California, Berkeley, (http://elsa.berkeley.edu/wp/train0899.pdf). 34