Authority, Incentives and Performance: Theory and Evidence from a

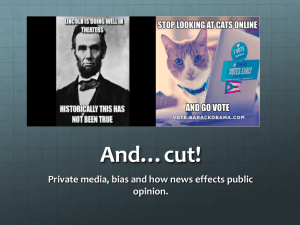

advertisement