Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

www.elsevier.com/locate/foodqual

Exploring consumersÕ perceptions of local food with two

different qualitative techniques: Laddering and word association

Katariina Roininen *, Anne Arvola, Liisa Lähteenmäki

VTT Biotechnology, P.O. Box 1500, FIN-02044 VTT, Finland

Received 28 September 2004; accepted 29 April 2005

Available online 28 June 2005

Abstract

In recent years, a growing number of consumers in Finland have started to show interest in the origin of the foods they eat.

Although the concept of local food has been launched to describe food produced near the consumer, it is not yet well-defined

and consumers may understand it in different ways. The aim of the study was to establish the personal values, meanings and specific

benefits consumers relate to local food products by comparing two different qualitative interview techniques: laddering and word

association methods. Product names, presented as cards for participants, were used as stimulus material. In the word association

(n = 25), four product categories (general term, fresh pork meat, marinated pork slices, and pork sausage) and of four types of production method or production location (locally, organically, conventionally and intensively produced) were presented. In laddering

(n = 30), the production methods were the same as in the word association method, with the exception that there were only two

product categories, instead of four. The content analysis of the participantsÕ responses resulted in very similar categories in both

studies, such as ‘‘quality’’, ‘‘locality’’, ‘‘vitality of rural areas’’, ‘‘short transportation distances’’, ‘‘freshness’’, and ‘‘animal wellbeing’’. Only the laddering study, however, revealed cognitive structures, i.e., links between such constructs as ‘‘short transport’’

and ‘‘animal welfare’’. Word association was found to be an efficient and rapid method for gathering information on consumer perceptions of local foods. Laddering interviews, which were time-consuming and required laborious analysis, provided us with important information on the relationship between perceived attributes and the reasons for choices.

2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Local; Organic; Laddering; Word association

1. Introduction

Interest in the origin of foods and in the production

method has increased among Finnish consumers in recent years. The concept of local food has been launched

to describe local food systems or short food chains

where the food is produced near the consumer; this

could contribute to rural development and labor markets to promote local economies (Urban–Rural Interaction, 2001). This concept is not, however, well-defined

*

Corresponding author. Tel.: +358 9 708 58724; fax: +358 9 708

58212.

E-mail address: katariina.roininen@vtt.fi (K. Roininen).

0950-3293/$ - see front matter 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2005.04.012

yet, due to which it can mean different things to different consumers. It is not clear what consumers exactly

appreciate in local foods and whether these valuations

differ from those that they associate with organic foods.

In order to promote marketing possibilities for local

foods, it is important that we understand how consumers perceive the concept of local food and what advantages or disadvantages and values they relate to the

concept.

In the case of a new concept, qualitative methods are

suitable tools for revealing how consumers view and

perceive that concept. Word association techniques,

which are commonly applied in psychology, are qualitative methods that could serve as quick and convenient

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

tools in exploring consumer perceptions for new and

undefined concepts such as local food. Word association

may be less laborious than many other qualitative methods, such as personal interviews. Most importantly,

indirect associative techniques are able to grasp affective

and less conscious aspects of respondentsÕ mindsets better than methods that use more direct questioning (Szalay & Deese, 1978). Based on the expectancy-value

theories of Ajzen and Fishbein (1980), the most salient

associations or beliefs that the consumers has about

the attitude object in question are the best predictors

of the consumerÕs behaviour related to that attitude object. Thus, the associations that first come to the respondentÕs mind are the ones that should be the most

relevant for consumer choice and product purchase. Slovic et al. (1991) and Benthin et al. (1995) have demonstrated an application of a word association technique

where respondents are asked, not only about their associations, but also to score their responses as regards to

their valuations. Thus, the method applied in this

fashion provides both a qualitative understanding of

the beliefs behind the attitudes as well as quantitative

estimates of the attitude valence (unfavourable/favourable). At its best, this method could provide fast and

convenient tool for exploring the motives behind food

choice. At its worst, though, it could provide results that

are shallow and difficult to interpret.

Laddering interviews are another qualitative method

that can provide both the perceptions of the local food

concept and a comprehensive investigation of the structure of the concepts that are relevant for the respondent.

It provides a method that can capture the salient attributes of product choices, which then lead to the benefits

and values that these attributes signify to a person. It is

based on the means-end theory, which is a model of the

consumersÕ cognitive structures that focuses on how

product attributes (the ‘‘means’’) are linked to self-relevant consequences and personal values (the ‘‘ends’’)

(Olson, 1989; Reynolds & Gutman, 1988). Laddering

provides a rich and useful understanding of consumers

perceptions of products and the basis for their purchase

decisions. The advantage of the laddering technique

over other qualitative approaches is that the meanings

in a means-end chain are personally relevant; therefore,

laddering could provide results that are more closely related to preference and choice behaviour (Olson, 1989).

This approach has previously been shown to be useful

tool in analysing consumer behaviour in the food domain (Baker, Thompson, & Engelken, 2004; Grunert

et al., 2001; Makatouni, 2002; Nielsen, Bech-Larsen, &

Grunert, 1998; Roininen, Lähteenmäki, & Tuorila,

2000; Urala & Lähteenmäki, 2003).

The aim of this study was to establish the personal

values, meanings and specific benefits consumers relate

to local food products by comparing word association

and laddering methods as elicitation techniques.

21

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

This study consisted of two parts: word association

and laddering interviews. Both parts were conducted

in two different locations, Mikkeli and Espoo, in Finland. Mikkeli is a small town in eastern Finland and

Espoo is part of the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. Espoo

was chosen to represent an urban area that is far from

production and Mikkeli to represent as location that is

in the middle of a rural, agricultural area. For the word

association interviews (n = 25; 15 participants from

Espoo and 10 from Mikkeli; 40% of which were males

and 60%, females), the mean age of the participants in

Espoo was 39 (range: 19–68) and in Mikkeli, 42 (range:

18–68). In the laddering interviews (n = 30; 15 participants in Espoo and 15 participants in Mikkeli; 54% of

which were males and 46%, females), the mean age of

the participants in Espoo was 49 (range: 18–67) and in

Mikkeli, 44 (range: 20–64).

2.2. Word association

The applied method relies on the word association

method demonstrated by Slovic et al. (1991) and Benthin et al. (1995). It involves presenting subjects with a

target stimulus and asking them to provide the first

thoughts or images that come to mind. In this study,

the target stimuli were written descriptions of pork meat

products. The descriptions were combinations of three

types of products with varying levels of processing (fresh

pork meat, marinated pork slices, and pork sausage)

and of four types of production method or production

location (locally, organically, conventionally and intensively produced), such as ‘‘locally produced sausage’’

or ‘‘conventionally produced marinated pork slices’’.

In addition, the four production methods were presented as general descriptions without any reference to

a specific product, e.g., ‘‘organically produced food’’.

Each of the (n = 25) respondents were shown (4 · 4) 16

cards, one at a time, in a random order. The respondents

were asked to write down the first four images, associations, thoughts or feelings that came to mind. After

going through the 16 stimulus descriptions, the participant was asked to rate each association that he or she

had written on the questionnaire on a scale from 1 (very

negative/bad) to 5 (very positive/good). At the end, the

participants answered a few background questions

about their age, gender, education, and familiarity of

terms local and organic food (on scale from 1 = very

unfamiliar to 5 = very familiar).

The data were collected in Espoo and Mikkeli during

autumn 2003. In both places, the interviews took place

in coffeehouses. After completing the task, each respondent received a gift voucher, ranging in value from EUR

22

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

5 to 8, depending on the place, to the coffeehouse where

the interview took place.

2.3. Laddering interviews

In laddering interviews, the types of production

methods or production location (locally, organically,

conventionally and intensively produced) were the same

as those in the association task, with the exception that

only two product categories were used (fresh pork meat

and marinated pork slices). Both product categories

were presented to each participant. The order of the

food category was randomised. The one-to-one interviews were divided into two parts: sorting (part A) and

the main interview (part B). The session started with

an explanation of the study tasks that emphasised that

‘‘there were no right or wrong answers’’ to the questions, and that researchers were only interested in the

participantsÕ opinions. In part A, participants were instructed to sort the foods by their choice priority. In

the main interview (part B), participants were asked

about the reasons for their first choice compared to

other choices. They were then further asked ‘‘why is this

reason important to you?’’ The laddering process continued in this manner until the participant could not

produce any further information. This was then repeated for their second, third and last choice. After part

B, the participants were asked to fill out a background

questionnaire on their age, gender, education, and their

use frequencies of the target foods. The interviews took

between 30 min and 1 h to complete. The participantsÕ

responses were recorded on pre-prepared answering

sheets by the interviewer during the course of the interview. In addition, the interviews were tape-recorded. In

Espoo, the interviews took place in two coffeehouses

and in Mikkeli, in a room provided by the YTI Research

Centre. After completing the task, each respondent received a small gift (in Mikkeli, which was worth EUR

6), a cinema ticket (worth EUR 7) or a gift voucher

(worth EUR 6) to the coffeehouse where the interview

took place (in Espoo).

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Word association

Quantitative estimates of the attitudes towards the

stimuli were obtained by averaging the ratings of the

four images that the respondent had provided for each

stimulus. Normality of the distributions was tested by

one sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test. All

variables used in the analyses were normally distributed

based on this test. Therefore, parametric tests could be

used for these analyses. Repeated measure analyses of

variances were used to compare these attitudes (or

image ratings) between the stimuli. Comparisons were

made (independent within subjects variables) between

the production methods/production distance (locally

produced, organic, conventionally produced, intensively

produced) and product type (raw pork meat, marinated

pork slices, sausage), with the interview location (Espoo,

Mikkeli) acting as the subject variable. In addition to

mean ratings, we also calculated the percentages of associations that gave a positive or negative score for each

stimulus. The software used for the quantitative analyses was SPSS.12.0 for Windows (2003).

The elicited associations were qualitatively analysed

by means of content analysis. The analysis proceeded

sequentially from the initial search of recurrent themes

to the classification of each elicited association into

one of the 32 categories. Finally, these categories were

reduced to the 18 categories presented in this article.

Ten was used as the reduction cut-off, i.e., the association need to be mentioned at least 10 times when all

the products were combined.

2.4.2. Laddering interviews

Information collected during the interviews was content analysed. In the content analysis, the attributes and

consequences having the same meaning were grouped

together and each group was labelled. These groupings

formed a scheme that was used to categorise the attributes and consequences. Once the content analysis

had been performed, the laddering data, e.g., the attributes and their consequences, were aggregated and

interpreted through hierarchical value maps (HVM),

which are graphical representations of the most frequently mentioned links summed across all subjects.

These graphic maps were generated using MecAnalyst

software (Skymax Inc., Italy) which is tailored to analysing means-end chains. The number of links between

the concepts reflects the complexity of the map and

the strength of the line illustrates the number of participants that mentioned the link. The software forms individual chains and then analyses the number of links

across the study population. A cut-off level of four

was chosen, except in the case of conventionally produced food, where a cut-off level three was selected. A

cut-off level of four means that a link is drawn between

two concepts if at least four of the participants mentioned one concept as a direct or indirect link to another concept.

3. Results

3.1. Word association

In word association, term local food was regarded

familiar (values 4–5 on familiarity scale) by 80% of participants from Mikkeli and 20% by participants from

Espoo. There was no difference in familiarity of organic

food between the two locations.

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

For all product categories, locally, organically and

conventionally produced foods received mostly positive

associations. On the other hand, intensively produced

food evoked mostly negative associations. Freshness,

short transport, security as well as contribution to local

economy and viability were associated with local food

production. The transparency of locally produced food

23

was considered good. This was expressed in associations

such as ‘‘knowing what theyÕre getting’’, ‘‘knowing

where the food came from’’, and ‘‘trustworthiness’’.

The only negative association that was related to locally

produced food was price, which was considered to be

high. Expensive pricing was, however, more often associated with organically produced than locally produced

Table 1

Association categories and examples of individual associations

Category

Examples

Local

Organic

Conventional

Intensively

Total

Wholesome

Healthy (l, o), low-fat (l, o),

unhealthy (c, i), high-fat (c, i)

6

1; 0; 5

16

0; 1; 15

13

10; 2; 1

10

10; 0; 0

45

21; 3; 21

Clean

No additives (l, o, c), no preservatives (o),

additives or preservatives can be added

(c, i), more additives (i), preservatives (i)

5

0; 2; 3

32

0; 2; 30

11

6; 3; 2

15

13; 2; 0

63

19; 9; 35

No pesticides

No pesticides (o), pesticides can be used

(c), may contain antibiotic substances (i)

0

0; 0; 0

12

0; 1; 11

3

2; 1; 0

13

0; 0; 13

28

2; 2; 24

Organic, natural

Organic (l, o), natural (o), not organic (c),

unnatural (i)

7

0; 2; 5

17

0; 1; 16

5

1; 3; 1

7

7; 0; 0

36

8; 6; 22

Quality, taste

Do not affect taste (l), good taste and

quality (l, o, c), conventional (c),

bad taste and quality (i)

38

4; 2; 32

49

0; 1; 48

44

14; 12; 18

43

34; 3; 6

174

52; 18; 104

Fresh

Fast delivery (l), fresh (l, o, c)

20

0;0; 20

3

0; 0; 3

2

1; 0; 1

0

0; 0; 0

25

1; 0; 24

Conflict between processing

and production

The idea of local product is spoiled by

the marinade (l, o), marinated

product cannot be organic (o), negative

effect of marinade (c)

4

1; 3; 0

13

5; 8; 0

5

1; 4; 0

0

0; 0; 0

22

7; 15; 0

Inform and security

Trust (l, o), origin is known (l), good

quality control (c), lack of confidence (i)

16

0; 5; 11

1

0; 0; 1

9

4; 2; 3

13

9; 2; 2

39

13; 9; 17

No added value of

production method

Does not affect buying decision or

food choice (l, i), quality product is enough (o)

15

1; 5; 9

2

1; 0; 1

4

0; 4; 0

2

1; 1; 0

23

3; 10; 10

Availability, selection

Availability not good (l, o), not many

alternatives (o), conventional food (c, i),

limited selection (o)

14

3; 4; 7

16

9; 4; 3

17

2; 4; 11

7

0; 4; 3

54

14; 16; 24

Price (cheap)

Expensive (l, o), good buy (c, i),

special offer product (i)

11

8; 2; 1

34

28; 6; 0

18

3; 4; 11

18

0; 2; 16

81

39; 14; 28

Animal welfare

Animal welfare (l, o), awareness of animal

treatment (l, o, c), animal welfare is ignored (i)

8

0; 0; 8

19

0; 0; 19

2

0; 0; 2

19

19; 0; 0

48

19; 0; 29

Affects viability of countryside

Affects viability of countryside (l), good for

economy (l), creates unemployment (i)

20

0; 1; 19

0

0; 0; 0

0

0; 0; 0

1

1; 0; 0

21

1; 1; 19

Transport, costs

Low transport costs (l), long transport (i)

11

1; 0; 10

0

0; 0; 0

0

0; 0; 0

1

0; 0; 1

12

1; 0; 11

Local

Local product (l), produced locally (l, o),

industrial product (i)

29

0; 2; 27

3

0; 0; 3

0

0; 0; 0

0

0; 0; 0

32

0; 2; 30

Large production unit

Large production units (l, o, i), profit seeking (i)

2

0; 0; 2

0

0; 0; 2

18

2; 11; 5

60

38; 14; 8

80

40; 25; 15

Small production

unit, traditional

Homelike (l, o), self-produced (o, c),

traditional (o, c)

19

0; 2; 17

32

0; 3; 29

24

0; 3; 21

0

0; 0; 0

75

0; 8; 67

Products

Products of Portti in Mikkeli (l), vegetables (o),

convenience foods (c), chicken (i)

8

0; 3; 5

8

0; 0; 8

16

3; 5; 8

13

8; 1; 4

45

11; 9; 25

In each column, below the total number is number of negative, neutral and positive associations.

(l) = local, (o) = organic, (c) = conventional and (i) = intensive.

24

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

food. In general, organically produced food aroused

more associations such as the purity (no added additives

or very few) of the product and the production method,

wholesomeness, good taste and quality, animal welfare

and small-scale production than locally produced

food. Good quality, affordable price, easily available,

unhealthy, impure and industrially produced were associations that were more often connected with conventionally produced food than locally produced foods.

Most of the terms evoked by intensively produced food

were considered negative such as cruelty to animals, pesticides, unhealthy, unnatural and large-scale production.

Intensively produced food was, however, considered to

be cheaper and better in quality than local food (Table

1).

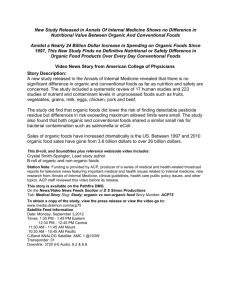

Value scores were significantly different for the different production methods when the all 16 terms were included in the analysis (F(3, 69) = 69.4; p < 0.001) (Fig.

1). Although the number of associations linked to the

organically produced food was higher than those for locally produced food, the value scores of organically produced food were lower compared to locally produced

food generally speaking. Interaction between the production method and degree of processing was observed

(F(6, 138) = 4.9; p < 0.001). The value scores of organically produced food were lower when the degree of production was higher (F(2, 46) = 8.6; p < 0.001). In the

case of intensively produced food, foods that were more

processed received higher value scores than foods that

were not processed (F = (2, 46) = 4.3; p < 0.05). The degree of processing did not significantly affect the scores

of locally and conventionally produced foods and no

difference was observed between pork sausage and marinated pork slices. The interview location did not significantly influence the association value ratings.

Locally produced

Organically produced

3.2. Laddering

In laddering interviews, term local food was regarded

familiar (values 4–5 on familiarity scale) by 67% of participants from Mikkeli and 40% by participants from

Espoo. Whereas, 73% of participants from Mikkeli

and 67% of participants from Espoo regarded organic

food familiar.

Choices in the sorting part (A) varied between different production methods and interviewing locations but

not between products. Therefore, the choice data of

products is combined. In Mikkeli 33% of participants

chose local food, 55% organic, 13% conventional and

3% intensively produced food as their first choice.

Whereas, in Espoo 30% of participants chose local food,

33% organic, 33% conventional and 3% intensively produced food as their first choice.

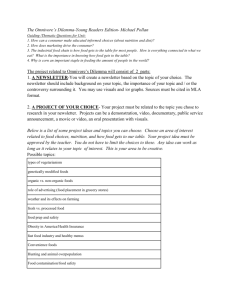

The maps of locally produced food noticeably differed between the two locations (Fig. 2a and b). In both,

the short transportation distance was given as a reason

for preference, leading to fresh product quality and the

Finnish origin of products creating a sense of security.

In Mikkeli, however, the local food was mostly considered a way to support local production and to create

economic welfare in the area; whereas, local food was

linked with animal welfare, environment and health in

Espoo, which was quite similar to their perception of organic products (Fig. 3a). Moreover, the attribute-consequence links were more concrete in Mikkeli than in

Espoo; for example, in Mikkeli, short transportation

distance was related to good taste, lower price, freshness

and saving money. In Espoo, this was related to animal

welfare and respect for nature.

Local food was perceived similarly to organic food in

Espoo (Figs. 2a and 3a); in Mikkeli, the perception was

Conventionally produced

Intensively produced

5

4.5

Value score

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

General term

Fresh pork meat

Marinaded pork slices

Pork sausage

Fig. 1. Affect scores of four types of production methods (locally, organically, conventionally and intensively produced) with four types of products

(general term, fresh pork meat, marinated pork slices, and pork sausage).

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

25

Cut-Off=4

Well-being

Environment

stays clean

Creates no

waste

Avoid

diseases

Quality of life

Animal

welfare

Does not

spoil

Creates

employment

Respect for

nature

Good

for health

Creates

security

Like to

support

Stays fresh

Can do

alternative

activies

Short

transport

Finnish

Familiar

a

Cut-Off=4

Common

good

Subsistence

wages

Creates

employment

Affects

viability of

countryside

Stays fresh

Tastes good

Creates

security

Like to

support

Avoid

diseases

Lower price

Local

Short

transport

Finnish

Saves

money

Improves

quality

b

Fig. 2. Hierarchical value map of locally produced foods (data from fresh pork meat and marinated pork slices combined): (a) for participants from

Espoo and (b) participants from Mikkeli.

close to that of conventional production (Figs. 2b and

4b). The overall picture of organic products in the hierarchical value maps is similar in the two towns with animal welfare, good taste and respect for nature included

on the map. The ladders describing conventional production are, however, dissimilar in the two locations.

For Mikkeli, the value map is a complex picture with

many attributes that link conventional production to

health, nature and well-being and the map is comparable to that of local food. In Espoo (please note the

cut-off point of 3), the conventional production is considered to be practically neutral, not expensive and an

easily available option.

Intensive production is perceived with parallel

negative attributes in Espoo and Mikkeli (Fig. 5a and

b). Intensive production means cruelty to animals

and is bad for health. The hierarchical value maps

also have very simple structures indicating that respondents perceived intensive production in a stereotypic

manner.

26

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

Cut-Off=4

Balance of

nature

Respect for

nature

Well-being

Recreactional

value of environment remain

Enjoys

Avoid

diseases

Good for

health

Animal

welfare

Creates no

waste

Chemicals do

not cumulate

Fresh

Environment

stays clean

Tastes good

Improves

quality

Animalfriendly

Organic

animals

a

Cut-Off=4

Quality of life

Improves

quality

Well-being

Happiness

Pleasure

Enjoys

Will not

purchase

Avoid

diseases

Animal

welfare

Chemicals

do not

cumulate

Tastes good

Good physical

condition

Expensive

Organic animals

Clean

Organic

Good quality

b

Fig. 3. Hierarchical value map of organically produced foods (data from fresh pork meat and marinated pork slices combined): (a) for participants

from Espoo and (b) participants from Mikkeli.

3.3. Comparison of word association with laddering

results

Both the association and laddering methods gave

similar descriptions for locally produced food such as

positive effects on food quality, locality, viability of local

areas, short transportation distances, freshness, and animal well-being. With word association, the number of

consequences from eating and buying these foods were

fewer than in laddering and the links between attributes

and consequences, e.g., association between short trans-

portation distances and animal well-being, were only

obtained with the laddering technique.

4. Discussion

In the present study, locally produced food was considered to support the local economy, was related to

short transport distance, freshness and trustworthiness

of its origin regardless of the elicitation method. The results are congruent with a previous focus group study

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

27

Cut-Off=3

Can do alternative

activities

Saves time

Easy

Can afford

Saves

money

Price not

expensive

Good

availability

a

Cut-Off=3

Pleasure

Can do

alternative

activies

Respect for

nature

Well-being

Enjoys

Can afford

Animal

welfare

Avoid

diseases

Saves

money

Good for

health

Familiar

Awareness

of animal

treatment

Know what

you get

Is important

Lower price

Clean

Safe

Animalfriendly

Price not

expensive

Large

production

unit

Good quality

b

Fig. 4. Hierarchical value map of conventionally produced foods (data from fresh pork meat and marinated pork slices combined): (a) for

participants from Espoo and (b) participants from Mikkeli.

about ecolabel prototypes that was carried out in three

locations in Iowa, USA. In that study, it was found that

for consumers, ‘‘freshness’’ and ‘‘supporting family

farmers’’ were the two most important reasons for buying local foods (Pirog, 2003).

Organically produced food evoked more associations

related to purity (no added additives or very few) than

locally produced food did. Getting clean food or food

free from pesticides or other chemicals have also been

found to be common benefits associated with organic

food in earlier studies (Baker et al., 2004; Grunert &

Juhl, 1995; Huang, 1996; Mathisson & Schollin, 1994;

Tregear, Dent, & McGregor, 1994). Moreover, healthi-

ness, and animal welfare were more associated with

organically than with locally produced food. Organically produced food, however, evoked more negative

associations, such as that it was more expensive than locally produced food. In addition, processing was not

considered appropriate in the case of organically produced food. Moreover, in many other studies, the main

benefits consumers have been found to associate with

organic foods (or indicate as their reasons for buying

them) are related to health, taste and environment; these

are among the most commonly mentioned characteristics or purchase motives of organic foods, regardless

of the country that the study took place in (Baker

28

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

Cut-Off=4

Animals are

stressed

Will not

purchase

Bad for

health

Creates

suspicion

Taste

deteriorates

Cruelty to

animals

Not animalfriendly

Not clean

a

Cut-Off=4

Develop

diseases

Taste

deteriorates

Animals are

stressed

Chemicals

cumulates

Cruelty to

animals

Profitseeking

Not animalfriendly

Deteriorates

quality

Not clean

Large

production

unit

b

Fig. 5. Hierarchical value map of intensively produced foods (data from fresh pork meat and marinated pork slices combined): (a) for participants

from Espoo and (b) participants from Mikkeli.

et al., 2004; Granqvist & Biel, 2001; Hill & Lynchehaun,

2002; Magnusson, Arvola, Koivisto-Hursti, Åberg, &

Sjöden, 2001, 2003; Roddy, Cowan, & Hutchinson,

1996; Saba & Messina, 2003; Tregear et al., 1994; Wandel & Bugge, 1997; Zanoli & Naspetti, 2002).

Differences between local and organically produced

foods are congruent with an earlier study by Winter

(2003). This study consisted of face-to-face interviews

with 736 residents from five regions in England and

Wales. Fifty four percent of the respondents claimed

that they made regular, weekly purchases of foods produced by local farms. The reasons that they gave for the

purchases of local food were related to supporting the

local farmers and the local economy, freshness and

knowing where their food was coming from. On the

other hand, health, food safety and environment were

stressed more often as the reasons for buying organic

food.

In the laddering results, a huge difference between the

constructs of the hierarchical value maps were observed

between participants from the rural area (Mikkeli) and

participants from the urban area (Espoo). Participants

from the rural area were more interested in supporting

the local economy than participants from the urban area

were. This is in accordance with earlier findings in the

UK (n = 734), where rural consumers gave higher priority to ‘‘civic’’ issues in food choice and showed higher

interest in local foods than urban consumers did

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

(Weatherell, Tregear, & Allinson, 2003). The reason for

this might be that participants from the rural area are

closer to sources of food production. Therefore the concern of local economic issues might be greater.

Both association and laddering methods gave similar

descriptions for the foods produced. As expected, word

association provided a useful approach for examining

the images and outcomes participants associated with

local food. This is in accordance with the study of Benthin et al. (1995), who found word association to be a

useful method for eliciting positive and negative affects

associated with the behaviour of adolescents. The laddering technique, however, provided an overview of

the characteristics of locally and organically produced

foods as well as information on why these characteristics

are important to the participants. Laddering has been

found to be a very useful method in understanding the

self-relevant consequences consumers attach to food

products (Baker et al., 2004; Grunert, Grunert, & Sørensen, 1995; Grunert et al., 2001; Nielsen et al., 1998).

Moreover, the differences between rural and urban participants were mainly observed by the laddering technique. Differences between the degree of processing

was observed when the association technique was used;

the same was not observed with the laddering technique.

In the laddering the participants sorted different production methods by their choice priority and this was done

separately for both products that different in processing

level therefore they might paid more attention in comparison of different production methods than comparison of different level of processing.

Word association was found to be an efficient and

rapid method to gain information about consumer perceptions of local foods. Product attributes may, however, not be sufficient by themselves and the link they

have to one or more desirable or undesirable consequences is more important. Laddering interviews were

time-consuming and the analysis of laddering data was

a laborious and relatively slow task. Laddering is,

though, a useful tool when the purpose is to get self-related information on the attribute–consequence–value

associations that consumers hold about a product.

The limitation of this study is that only small number

of respondents were used in both methods. Therefore,

generalization of the views consumers have about local

and organic foods is complicated. However, this study

gives good insight about advantages and disadvantages

of associations and laddering methods when these methods are used for getting information about the new concepts. The association method was found to be fast and

useful in situations when information about product

attributes is sufficient themselves. When association

method was used, it was not possible to get values and

links between attributes, consequences and values. Because association method was faster, more respondents

could be used, and this would make the results more eas-

29

ily generalized. Laddering, in turn, was found to be

more time-consuming than association method. However, it gave more information than association method.

Te use of laddering would be recommended in the situation when deep information about the concept is

needed.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the Consumers, decision makers

and local or organic foods. Possibilities for SMEs project

supported by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry

of Finland.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting

behavior. Engelwood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Inc.

Baker, S., Thompson, K. E., & Engelken, J. (2004). Mapping the

values driving organic food choice: Germany vs the UK. European

Journal of Marketing, 38(8), 995–1012.

Benthin, A., Slovic, P., Moran, P., Severson, H., Mertz, C. K., &

Gerrard, M. (1995). Adolescent health-threatening and healthenhancing behaviors: a study of word association and imagery.

Journal of Adolescent Health, 17, 143–152.

Granqvist, G., & Biel, A. (2001). The importance of beliefs and

purchase criteria in the choice of eco-labeled food products.

Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21, 405–410.

Grunert, K.G., Grunert, S.C., & Sørensen, E., (1995). Means-end

chains and laddering: An inventory of problems and an agenda for

research (Working paper No. 34). Aarhus: The Aarhus School of

Business, MAPP.

Grunert, S. C., & Juhl, H. J. (1995). Values, environmental attitudes,

and buying of organic foods. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16,

39–62.

Grunert, K., Lähteenmäki, L., Nielsen, N. A., Poulsen, J. B., Ueland,

O., & Åström, A. (2001). Consumer perceptions of food products

involving genetic modification—results from a qualitative study in

four Nordic countries. Food Quality and Preference, 12, 527–542.

Hill, H., & Lynchehaun, F. (2002). Organic milk: attitudes and

consumption patterns. British Food Journal, 104(7), 526–542.

Huang, C. L. (1996). Consumer preferences and attitudes towards

organically grown produce. European Review of Agricultural

Economics, 23, 331–342.

Magnusson, M., Arvola, A., Koivisto-Hursti, U.-K., Åberg, L., &

Sjöden, P.-O. (2001). Attitudes towards organic foods among

Swedish consumers. British Food Journal, 103(3), 209–226.

Magnusson, M. K., Arvola, A., Koivisto Hursti, U.-K., Åberg, L., &

Sjödén, P.-O. (2003). Choice of organic foods is related to

perceived consequences for human health and to environmentally

friendly behaviour. Appetite, 40, 109–117.

Makatouni, A. (2002). What motivates consumers to buy organic food

in the UK? Results from a qualitative study. British Food Journal,

104(3/4/5), 345–352.

Mathisson, K., & Schollin, A., (1994). Konsumentaspekter på ekologiskt odlade grönsaker—en jämförande studie (Consumer aspects on

organic vegetables—a comparative study) (No. 18). Uppsala:

Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, Institutionen för växtodlingslära.

Nielsen, N. A., Bech-Larsen, T., & Grunert, K. G. (1998). Consumer

purchase motives and product perceptions: a laddering study on

vegetable oil in three countries. Food Quality and Preference, 9(6),

455–466.

30

K. Roininen et al. / Food Quality and Preference 17 (2006) 20–30

Olson, J. C. (1989). Theoretical foundations of means-end chains.

Werbeforschung & Praxis Folge, 5, 174–178.

Pirog, R. (Ed.). (2003). Ecolabel value assessment consumer and food

business perceptions of local foods. Iowa: Leopold Center for

Sustainable Agriculture and the Iowa State University Business

Analysis Laboratory.

Reynolds, T. J., & Gutman, J. (1988). Laddering theory, method,

analysis, and interpretation. Journal of Advertising Research, 2,

11–31.

Roddy, G., Cowan, C. A., & Hutchinson, G. (1996). Consumer

attitudes and behaviour to organic foods in Ireland. Journal of

International Consumer Marketing, 9(2), 41–63.

Roininen, K., Lähteenmäki, L., & Tuorila, H. (2000). An application

of means-end chain approach to consumersÕ orientation to health

and hedonic characteristics of foods. Ecology of Food Nutrition, 39,

61–81.

Saba, A., & Messina, F. (2003). Attitudes towards organic foods and

risk/benefit perception associated with pesticides. Food Quality and

Preference, 14, 637–645.

Slovic, P., Layman, M., Kraus, N., Flynn, J., Chalmers, J., & Gesell,

G. (1991). Perceived risk, stigma and potential economic impacts of

a high-level nuclear waste repository in Nevada. Risk Analysis, 11,

683–696.

Szalay, L., & Deese, J. (1978). Subjective meaning and culture: An

assessment trough word associations. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tregear, A., Dent, J. B., & McGregor, M. J. (1994). The demand for

organically-grown produce. British Food Journal, 96(4), 21–25.

Urala, N., & Lähteenmäki, L. (2003). Reasons behind consumersÕ

functional food choices. Nutrion & Food Science, 33(4), 148–158.

Urban–Rural Interaction (2001). Report of the Working Group of

Urban–Rural Interaction, Ministry of the Interior, Helsinki.

Wandel, M., & Bugge, A. (1997). Environmental concern in consumer

evaluation of food quality. Food Quality and Preference, 8(1),

19–26.

Weatherell, C., Tregear, A., & Allinson, J. (2003). In search of the

concerned consumer: UK public perceptions of food, farming and

buying local. Journal of Rural Studies, 19, 233–244.

Winter, M. (2003). Embeddedness, the new food economy and

defensive localism. Journal of Rural Studies, 19, 23–32.

Zanoli, R., & Naspetti, S. (2002). Consumer motivations in the

purchase of organic food. A means-end approach. British Food

Journal, 104(8), 643–653.