Using job embeddedness factors to explain voluntary turnover in

advertisement

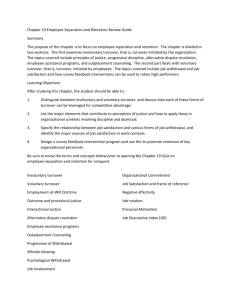

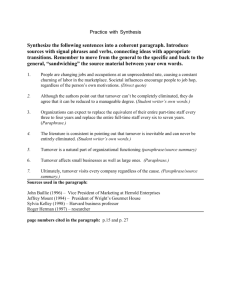

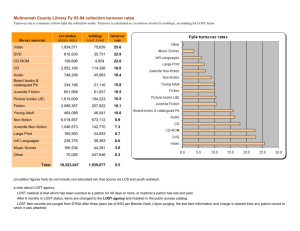

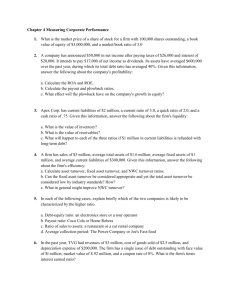

RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 19, No. 9, September 2008, 1553–1568 1 2 3 4 5 Using job embeddedness factors to explain voluntary turnover in four European countries 6 Cem Tanovaa* and Brooks C. Holtomb 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 a Faculty of Business and Economics, Eastern Mediterranean University, Gazimagusa, North Cyprus via Mersin 10; bMcDonough School of Business, Georgetown University, Washington, DC 20057, USA The aging of the European workforce coupled with existing deficits of skilled workers in vital sectors (e.g., information and communication technology) make the attraction and retention of skilled workers a critical strategic human resource management issue. The large-scale, multi-country study reported in this article investigates the causes of voluntary turnover. The study is based on a large European dataset that contains information about a wide variety of variables that have been shown to influence voluntary turnover. The results indicate that the traditional turnover model, where ease of movement and desirability of movement are regarded as important predictors of turnover, receives support. Importantly, the study also shows that a new theory of employee retention – job embeddedness – explains a significant amount of variance above and beyond the role of demographic and traditional variables. In sum, the evidence suggests that the turnover decision is not only about the individual’s attitudes towards work or about the actual opportunities in the labour market, but also job embeddedness. Keywords: job embeddedness; voluntary turnover; ease of movement; desire of movement 24 25 26 27 Introduction 28 29 The attraction, development and retention of skilled employees are critical issues for organizations and nations. While enlargement of the European Union and intensified European integration have introduced the possibility of greater labour mobility, there continue to be marked differences between the EU and United States. Data from Eurostat indicate that in a given year approximately 1% of the EU population changes region, compared with nearly 6% who moved from one county to another in the United States (Fuller 2002). The same dataset shows that Europeans are half as likely to change jobs as Americans in a given year. Given these differences between Europe and the United States and the fact that the vast majority of academic research on voluntary turnover has been published using models and samples from the United States, there is an urgent need to rigorously test the generalizability of these models in the European context. From the perspective of the organization, employee turnover creates both tangible and intangible costs. The tangible costs include recruitment, selection, training, adjustment time, possible product and/or service quality problems, and the costs of agency workers/temporary staff (Morrell, Loan-Clarke and Wilkinson 2004a). The intangible costs, which may be even more significant than the tangibles, involve the effect of turnover on organizational culture, employee morale, social capital and organizational memory (Morrell et al. 2004a). 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 *Corresponding author. Email: cem.tanova@emu.edu.tr 48 49 ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online q 2008 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/09585190802294820 http://www.informaworld.com RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1554 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 C. Tanova and B.C. Holtom At the national level, some labour mobility is viewed as positive for national economies because of job mismatches (Jovanovic 1979). Some employees may have accepted a job that was below their abilities in difficult times and they may wish to switch when they find the opportunity. Or some organizations may have employed an individual who was not a good match for the position. Jovanovic (1979) views jobs as ‘experience goods’ and as ‘search goods’. Based on the job employee matching model, workers move across jobs in order to find a good match which pays for their aptitudes and meets their expectations (Davia 2005). For an individual, turnover (including both voluntary and involuntary) will mean making a break with existing social networks, the stress of a new environment and an adjustment process. For some employees there may be direct losses related to benefits that they were receiving as being part of the organization (Griffeth, Hom and Gaertner 2000). There may also be some advantages. For example, Davia (2005) reports that employees at the early stages of their career who voluntarily leave, experience positive increases in their wages compared to those that do not change jobs. Furthermore, Davia (2005) found that turnover may pay in the mid-term even for involuntary movers although at a decreasing rate. One reason that a high rate of voluntary turnover is alarming for many managers is the fear that the employees with better skills and abilities will be those who are able to leave whereas those who remain will be those who cannot find other jobs. Thus, while voluntary turnover may be beneficial to the employee, it may not be for the organization. Though additional factors beyond individual preferences come into play especially in the European context (e.g., there are many other issues that prevent employees from leaving other than not finding alternative jobs), this topic merits rigorous scientific attention because of the significant consequences at the individual, organizational and national levels. Not surprisingly, turnover continues to be a topic of interest among researchers from disciplines such as management, psychology, economics and sociology. Shaw, Delery, Jenkins and Gupta (1998) report over 1,500 studies on the subject. There have also been several metaanalyses on the determinants of turnover (Cotton and Tuttle 1986; Cohen 1993; Hom and Griffeth 1995; Griffeth et al. 2000). Yet, there still is no universal agreement on the factors that explain why some employees leave and some stay. Simple logic suggests that assuming employees have viable job alternatives, if they are satisfied with their current job they will stay, but if they aren’t they will leave (Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski and Erez 2001). However, scientific literature shows that work attitudes (like job satisfaction) play only a relatively small role overall in turnover (Hom and Griffeth 1995; Griffeth et al. 2000). After a comprehensive review of the turnover literature Morrell, Loan-Clarke, and Wilkinson (2001) conclude that there is need for new theory in the study of turnover. The purpose of this article is to test a relatively new theory of employee retention (job embeddedness) developed and tested in the United States to assess its generalizability in the European context. 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 Turnover models Much of the current theoretical and empirical work on the topic of turnover is based on March and Simon’s (1958) foundation. They emphasized that employees’ degree of perceived ease of movement and perceived desirability of movement determines their likelihood of seeking a new job. The desirability of movement depends on job-related attitudes and internal opportunities while ease of movement depends on external factors such as availability of alternative jobs and unemployment levels. It is possible to distinguish turnover models as being from either the ‘psychological school’ or ‘labour market school’ (Morrell et al. 2001). The labour market school focuses on employees as rational, homogeneous and equally affected by external factors. The emphasis may RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 The International Journal of Human Resource Management 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 1555 be interpreted as deterministic since external influences are seen to determine actions (Morrell et al. 2004a). The topics discussed include job search (Fahr and Schneider 2004; Mano-Negrin and Tzafrir 2004), labour market flexibility, job mobility and wage mobility (Royalty 1998; Davia 2005), unemployment level (Trevor 2001) and person-job matching (Jovanovic 1979). The psychological school focuses on topics related to explaining or predicting leavers’ behaviour. The emphasis can be interpreted as voluntary, since individual choice is emphasized (Morrell et al. 2004a). The topics discussed are individual characteristics, stress, burnout, emotional exhaustion, personality, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and job involvement (Hom and Kinicki 2001). Further, a general withdrawal construct has been proposed whereby individuals engage in activities (e.g., lateness, absenteeism, diminished performance) that are seen as leading indicators of turnover (Hulin 1991; Sablynski, Mitchell, Lee, Burton and Holtom 2002). More recently the image theory of decision making has been integrated with the unfolding model of turnover (Lee and Mitchell 1994; Morrell et al. 2004a; Morrell, Loan-Clarke and Wilkinson 2004b). This approach demonstrates that for many the decision to leave is not the result of gradual built up of negative attitudes but rather the result of a shock, or some event that is significant enough to overcome the existing inertia. A new construct, job embeddedness, is conceptualized as influencing the decision to remain through the level of links a person has to other people or activities, the extent that the person’s job and community are congruent with the other aspects of their life, and the sacrifices a person would make in the process of leaving their employment (Mitchell et al. 2001). The well-known work of Granovetter (1985) introduced ‘embeddedness’ as a way to explain how social relations influence economic action. Building on this idea, the ‘job embeddedness’ (Mitchell et al. 2001) construct views the individual as a part of a complex web of relationships and attachments. The more extensive the web is, the more lines that connect the many aspects of the individual’s life. Thus, the more elaborate web will have a stronger influence on an individual who is considering making changes in one part of the web because that change will affect many other features of the individual’s life (Holtom, Mitchell, and Lee, forthcoming). The critical aspects of job embeddedness are: 1) the links that people have on and off the job; 2) the fit that they perceive between their self-concept and the environment that they live and work in; and 3) the sacrifices that they would make in giving up their job in terms of how this action would affect the other aspects of their life. Links, fit and sacrifice all have on-the-job and off-the-job dimensions. Links to the organization are the relationships that the individual has with the organization (e.g., department, work team) and the relationships that they have with others at work (e.g., coworkers, boss, mentor). The links to the community include the ties that the individual has in the area especially with friends, relatives and organizations. Fit with the organization assesses how the individual perceives their work in the organization and whether the individual feels that there is congruence between what she wants to do or can do and what she is actually doing. Fit with the community is the perception of fit between the individual’s concepts of the community that they would like to be a part of and the community that they actually live in. This includes the values of the community as well as the physical offerings such as housing and leisure activities. The sacrifice associated with leaving a job focuses primarily on the tangible losses that would be incurred if the individual left the job (e.g., benefits). Also, the community sacrifice dimension captures tangible losses involved if the employee was contemplating leaving the community because she was leaving the organization. Mitchell et al. (2001) conceive job embeddedness as a mediating construct between an individual’s work and personal life. Each dimension may have different degrees of importance for different individuals at different times or stages of their lives, however the magnitude of total RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1556 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 C. Tanova and B.C. Holtom embedding forces will have an influence on a person’s decision to leave. In 2001, Mitchell et al. produced evidence that job embeddedness predicts employee turnover over and above the effects of gender, psychological factors (e.g., job satisfaction), and labour market factors (e.g., job search behaviours). Further evidence of the predictive power of job embeddedness was presented in 2004 by Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton, and Holtom. In a large multi-national bank they found that job embeddedness not only predicts who leaves but also predicts in-role performance as well as extra-role performance. Additionally, Mallol, Holtom, and Lee (forthcoming) found that though levels of job embeddedness varied systematically between US born and non-US born employees (pre-dominantly Hispanic), the overall construct predicted voluntary turnover for both groups. The current article proposes a model that incorporates both the ease and desirability of movement variables together with job embeddedness factors to understand turnover using the available data from European Community Household Panel survey. 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 Expected relationships Personal characteristics Age Younger employees are more likely to take risks at the beginning of their careers. They are also more likely to accept positions that are below their abilities and expectations at the beginning of their career and move on to better jobs when those jobs become available. Meta-analytic research supports the negative age-turnover relationship (Griffeth et al. 2000). 170 171 172 Gender 173 Female workers traditionally have been seen as having a lower attachment to the labour force than men. However, in their meta-analysis, Griffeth et al. (2000) show only a negligible difference between men and women in terms of turnover (women are slightly more likely to leave their jobs than men). Further, Royalty (1998) found gender differences in turnover are due to the behaviour of less educated women (many of whom leave the labour force when they leave a job). In sum, educated women and men are very similar in their turnover behaviour. 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 Income As a person’s income from a job increases, the probability of their leaving the job decreases. This result has been demonstrated in diverse occupations, demographic groups, and across gender. Though the effect is typically modest (e.g., r ¼ 2 .11; Griffeth et al. 2000), it is persistent. Hypothesis 1: Age and income will be negatively related to voluntary turnover. 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 Desirability of movement Job satisfaction Job satisfaction has been found across many studies to be a reliable predictor of turnover, though the amount of variance explained is typically modest (Griffeth et al. 2000). Van Breukelen, van der Vlist and Steensma (2004) also show a negative relationship between job attitudes and turnover. Measuring job satisfaction at two different times before the measurement of leaving or staying, they find that there was stability in employees’ attitudes. However, they report that after RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 The International Journal of Human Resource Management 197 198 199 200 201 202 1557 the variance explained by intentions to leave the other variables did not explain much. Trevor (2001) analyzed interactions between actual ease of movement determinants such as education level and market conditions and found that when unemployment rates were low job satisfaction had greater impact on turnover decisions. Moreover, he found the effects of job satisfaction and unemployment rate depended upon levels of education, cognitive ability and occupation-specific training. 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 Ease of movement Unemployment level Armknecht and Early (1972) found that up to 78% of the variance in aggregate quit rate could be explained on the basis of present and expected economic conditions. Clearly, labour markets shape the quality and quantity of alternative opportunities (Mano-Negrin and Tzafrir 2004) and, thus, an individual’s behaviour or even attitudes are likely to be different in times of high versus low unemployment (Trevor 2001). 212 213 214 Education 215 Higher levels of education are likely to increase an individual’s turnover likelihood by increasing his or her opportunities. Moreover, an unobservable characteristic that could be associated with higher levels of education may be labelled ‘career mindedness’ (Royalty 1998). A career-minded individual would be more likely to take the risk of changing a job for potential improvements in their career. 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 Withdrawal behaviours Withdrawal According to Hulin (1991), individuals are likely to progressively enact more extreme manifestations of job withdrawal. This could begin with putting less physical and mental energy to their job, or going to work late and lead to absenteeism and eventually reaching voluntary turnover. With regard to behavioural predictors, the literature shows a small, positive relationship between job withdrawal behaviour such as tardiness or absenteeism and turnover (Griffeth et al. 2000). 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 Q1 243 244 245 Job search Another sign of possible withdrawal occurs when individuals start looking for other jobs. The turnover literature shows a strong, positive relationship between actual job search behaviours and turnover (Griffeth et al. 2000). Hypothesis 2: Desirability and ease of movement factors as well as withdrawal behaviours will predict variance in turnover beyond that explained by demographic variables and income. Job embeddedness As discussed previously, job embeddedness has explained variance in voluntary turnover above and beyond gender, desirability and ease of movement variables as well as job search behaviours (Mitchell et al. 2001). In that study and subsequently (Lee et al. 2004), job embeddedness has been operationalized as the combination of six factors: an employee’s fit with the community, fit RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1558 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 C. Tanova and B.C. Holtom with the organization, links with the community, links with the organization, sacrifice of leaving the community and sacrifice of leaving the organization. Put differently, an individual who has strong links to the community and the organization, who perceives that there is a good fit between her expectations and what the community and the organization is currently providing, and stands much to lose if these links are broken will be less likely to change jobs than a person who is less ‘embedded’. Hypothesis 3: Job embeddedness factors will improve the prediction of turnover beyond demographic factors, income, desirability and ease of movement and withdrawal behaviours. 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294 Method Data The European Community Household Panel (ECHP) survey is a harmonized, cross national annual longitudinal survey that focuses on household income and living conditions and provides information on employment and personal demographic characteristics. It has been collected since 1994 under Eurostat coordination. In the first wave approximately 130,000 adults aged 16 years and over were interviewed in about 60,500 nationally represented households in the then 12 member states. However not all countries entered the survey at the same time and for Germany, Luxembourg and United Kingdom the original sample has been replaced with harmonized versions of household panels already being produced nationally. For researchers a further anonimized sub-sample of the original data is available under strict contractual conditions. Further information on the ECHP and discussion on attrition, non-response, and weighing procedures can be found in Peracchi (2002). Some of the variables do not have identical response sets for some countries which limit the analysis that can be carried out using those variables. For example, the education level for the Netherlands seems to have been different after the third wave (i.e., some respondents who had higher levels of education were reported to have missing data or lower education levels in subsequent waves). Luxemburg, Ireland, Greece, Portugal, Austria, Sweden and The United Kingdom had many missing data for variables of interest in the current study and the question regarding reason for leaving the previous job in Germany indicated that there was a different set of responses used in this country in the recent waves of the survey, hence these countries were not included in the analysis. That allowed us to proceed with four European countries: Denmark, Italy, Spain, and Finland. Using the data for years 2000 and 2001 – the most recent waves – from the ECHP, we identified the individuals that had a full-time job (working at least 30 hours per week) other than self-employment in the year 2000 who were between the ages of 20 – 59. The age and the working hour limitations were used in order to focus on individuals who had a relatively stronger attachment to the labour market. The data for 2001 was then checked to see if the individual had changed jobs. This was done by looking at the responses to a question that asked the reason for stopping the previous job. The responses could be ‘obtained better/more suitable job’, ‘obliged to stop by employer’, ‘end of contract/temporary job’, ‘sale/closure of own or family business’, ‘marriage’, ‘child birth/need to look after children’, ‘looking after old, sick, disabled persons’, ‘partner’s job required to move to another place’, ‘study/national service’, ‘own illness or disability’, ‘wanted to retire or live off private means’, ‘other’ or ‘not applicable’. If the response was something other than not applicable this would indicate a stopping the previous job. To determine when the job change took place, we looked at questions that asked the year and the month of leaving the previous job, if this was some time RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 The International Journal of Human Resource Management 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 1559 after their ECHP survey in 2000 and before their ECHP survey in 2001, this indicated that the survey questions in 2000 were filled out before leaving the job and the 2001 survey would give us information on the person’s new condition. We created a turnover variable based on reason for leaving the previous job which placed individuals in three groups; ‘those that left their previous job voluntarily’, ‘those that had to leave their previous job’, and ‘those that did not change their job’. The data for the two years was then matched. Since the objective was to see how personal characteristics, satisfaction levels, and job embeddedness predict future turnover, we use measures of all independent variables from 2000 and the turnover data from 2001. 304 305 306 307 Measures 308 For each respondent three categories were available, those that left voluntarily, those that were forced leave their job (involuntary turnover) and those that stayed. 309 310 Voluntary turnover 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 Personal characteristics Age and gender were taken directly from the survey. Gender was coded 1 for male. Income The ‘income to occupational average’ variable was created by taking the purchasing power parity for each country, calculating the mean earnings from work for each of the nine occupation groups for the corresponding countries based on purchasing power parity, calculating the annual earnings from work for each individual based on purchasing power parity and dividing that figure to the related occupational average. Desirability of movement variable Job satisfaction for year 2000 was measured with a single question that asked in the year 2000: ‘Satisfaction with work’ the responses ranged from 1 not satisfied to 6 fully satisfied. 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 Ease of movement variables The unemployment rates for each country in year 2000 for men and women based on their level of education was taken from Eurostat database and was matched with the individuals based on sex, education level, and country in the dataset. The education level was measured based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Third level education (ISCED 5– 7) was coded as 3, second stage of secondary level education (ISCED 3– 4) was coded as 2, and less than second stage of secondary education (ISCED 0 –2) was coded as 1. 338 339 340 341 342 343 Withdrawal behaviours The question in the survey used to identify withdrawal behaviour/absenteeism – ‘how many days over the last four weeks other than holidays did you miss work?’ was used to measure absenteeism. RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1560 344 345 346 347 348 C. Tanova and B.C. Holtom Job search behaviour The question ‘are you currently looking for work’ was used as well as the response to ‘currently working but looking for more hours or different job’ to indicate that the respondent was looking for another job. 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 Job embeddedness As noted by Mitchell et al. (2001), job embeddedness is a formative measure. It represents a focus on the accumulated, generally non-affective, reasons why a person would not leave a job. Mitchell Q6 et al. (2001) further explained that ‘Job embeddedness is an aggregate multidimensional construct formed from its six dimensions (Law, Wong and Mobley 1998). More specifically, its indicators are causes of embeddedness and not reflections (MacCallum and Browne 1993)’. Thus, the measures that will be used to model job embeddedness are causal (and not effect) indicators. Also, as observed by Edwards and Bagozzi (2000), “associations of formative measures with Q2 their construct are determined primarily by the relationships between these measures and constructs that are dependent on the construct of interest’ (p. 159). This point is further clarified Q3 by Heise (1972) who noted that a construct measured formatively is not just a composite of its measures; rather, ‘it is the composite that best predicts the dependent variable in the analysis.... Thus, the meaning of the latent construct is as much a function of the dependent variable as it is a function of its indicators’ (p. 160). In sum, while we would prefer to have measured job embeddedness using the Mitchell et al. (2001) instrument, that was not possible in the current context. Thus, we have identified 16 items that closely resemble the items used by Mitchell and colleagues in the seminal papers on job embeddedness. There are at least two items for each dimension. Moreover, the items are substantially similar to an 18-item measure introduced Q4 recently by Mitchell and colleagues (Holtom, Tidd, Mitchell and Lee 2006). Regarding the questions in the ECHP that reflect job embeddedness, we recoded them so that higher scores (or 1 in the case of dichotomous variables) would be related to high embeddedness. Then, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation. The loadings of the variables are provided in Table 1. The links-community dimension was measured with a variable about marital status (1 ¼ married) and a variable regarding the presence of children in the household. The links-organization dimension was measured with the variable on job status (1 ¼ permanent) and a variable regarding job tenure. The fit-organization dimension was measured with questions related to having education or training related to the current job and whether this education or training contributes to the job. The fit-community dimension was measured with the variables ‘satisfaction with leisure activities’ and ‘satisfaction with housing situation’. The sacrifice-organization dimension was measured with several questions: ‘employer provides child minding or crèche – free or subsidized’, ‘employer provides health benefits – free or subsidized’, ‘employer provides education or training – free or subsidized’, ‘employer provides sports, leisure or vacation facilities’, and ‘employer provides housing – free or subsidized’. The sacrifice-community dimension was measured by home ownership, rent free housing and outstanding mortgage on the house. The mean of the six dimensions was calculated first. Then, the two sub-dimensions (embeddedness in the community and embeddedness in the organization) were calculated. Finally, they were combined to arrive at the overall level of ‘job embeddedness.’ Analysis In order to perform the analysis, we used the Cox Proportional Hazard Model: 391 392 hðtÞ ¼ ½h0ðtÞ exp ðb1X1 þ b2X2 þ . . . bkXkÞ ð1Þ 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 0.01 20.03 0.16 20.06 0.19 0.42 Notes: Extraction method: Principal component analysis; Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization. 0.07 0.08 20.12 0.00 0.02 0.39 414 20.01 412 413 20.01 411 0.02 410 0.10 409 0.06 407 0.11 406 0.12 404 405 0.05 0.01 0.25 2 0.05 0.22 0.26 0.03 2 0.04 0.94 0.93 0.53 20.04 20.07 0.16 2 0.09 0.00 0.00 0.15 2 0.01 2 0.04 0.11 0.03 0.02 2 0.07 0.23 0.08 Sacrificecommunity 0.60 0.69 0.59 0.63 20.03 20.02 0.07 0.08 0.11 0.07 0.02 0.00 0.48 402 0.08 401 20.03 400 2 0.04 2 0.11 0.09 2 0.01 0.03 0.03 0.78 0.70 2 0.20 399 20.05 0.00 0.09 0.00 0.94 0.95 0.04 0.03 20.06 398 Sacrificeorganization 396 397 0.41 20.08 0.74 0.85 0.04 0.05 0.04 0.04 0.06 403 Fit-community 395 0.66 0.86 0.08 20.02 20.02 20.01 20.13 0.01 20.08 408 Fit-organization 394 Marital status(1married) children under 12 in house(1 yes-0 no) Job status(1 permanent) Job tenure Has training or education related to job The training/education contributes to job Satisfaction with leisure Satisfaction with housing situation Employer provides child minding or crèche/free or subsidized Employer provides health benefits/free or subsidized Employer provides education or training/free or subsidized Employer provides sports, leisure or vacation facilities Employer provides housing/free or subsidized owns the home(1 yes-0 no) either owns or house is rent free(1 yes-0 no) there is outstanding mortgage (1 yes-0 no) 415 Links-organization 393 Links-community Table 1. Factor loadings of job embeddedness variables. RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1561 RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1562 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 C. Tanova and B.C. Holtom Where h(t) ¼ the hazard function at time t, h0(t) is the baseline hazard function for an individual if the value of all the independent variables could be zero. The independent variables were gender, age, income, higher education, relevant unemployment rate, job satisfaction, job search behaviour, absenteeism and embeddedness. The dependent variable was the dichotomous voluntary turnover variable, indicating whether the person left their job voluntarily. If they were forced to leave or stayed they were treated as ‘censored’. The model predicts the hazard function h(t), in our case the probability that an individual will leave their job voluntarily at time (t). Time was based on the question ‘when did you begin your present job’ that was asked in the year 2000, and the total time without a job change was calculated for the 2001 responses.The model does not make assumptions about the nature or shape of the hazard function; however it assumes that changes in levels of the independent variables will produce proportionate changes in the hazard function, independent of time. Also, it assumes a log linear relationship between the hazard function and the independent variables. The hazard function provides an estimate of the relative risk of voluntary turnover per unit time for an individual that has not left voluntarily up to that time. In the analysis exponentiated coefficients of the independent variables mean the expected change in h(t) for a unit change in the independent variable. 459 460 461 462 463 464 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 Results The means, standard deviations and correlations between variables are presented in Table 2. The average age of the respondents is 38.87. Of the respondents 61% are men. Although the figure varied by country, 29% of the respondents had university level education: 36% in Denmark 11% in Italy, 37% in Spain and 41% in Finland. We can see that men are more likely to leave voluntarily (r ¼ 0.04, p , 0.01). As predicted, age is negatively related to turnover (r ¼ 2 0.13, p , 0.01). The correlations are (r ¼ 2 0.18, r ¼ 2 0.10, r ¼ 2 0.15, r ¼ 2 0.13 all p , 0.01) in Denmark, Italy, Spain, and Finland. Income, which is the ratio of the respondents’ earnings from work to the average earnings in their occupation for their country, is negatively related to turnover (r ¼ 2 0.06, p , 0.01). This figure was fairly stable across countries: r ¼ 2 0.05, p , .05; r ¼ 2 0.07, p , .01, r ¼ 2 0.07, p , .01, r ¼ 2 0.07, p , .01 for Denmark, Italy, Spain, and Finland respectively. Hypothesis 1 is supported across the countries. With regard to desirability of movement variables, job satisfaction, as expected, was negatively related to the turnover decision (r ¼ 2 0.05, p , 0.01). Among ease of movement variables, unemployment was negatively related to turnover (r ¼ 2 0.04, p , 0.01). But, interestingly there was no significant relationship between having a university level education and leaving voluntarily. Of the withdrawal behaviours, job search behaviour was strongly correlated with turnover (r ¼ 0.15, p , 0.01). Absenteeism was not significantly related to turnover (r ¼ 2 0.01, ns). Job embeddedness was negatively correlated with turnover (r ¼ 2 0.10, p , .01). This relationship was highest (r ¼ 2 0.18, p , 0.01) in Spain and lowest (r ¼ 2 0.07, p , 0.01) in Italy. Job embeddedness was also positively correlated with job satisfaction (r ¼ 0.31, p , 0.01) and negatively correlated with job search behaviour (r ¼ 2 0.09, p , 0.01). It is also interesting to note that income was positively related to gender, which indicates men in general have higher earnings than women compared to the average in their occupation. Furthermore, there is a negative relationship between gender and unemployment. Since unemployment was calculated using unemployment rates based on gender and education level, the negative relationship between gender and unemployment shows women’s unemployment rates are higher compared to unemployment rates of men. 523 524 525 526 527 528 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 510 511 506 6 502 503 7 500 8 498 499 501 504 505 507 508 509 512 514 515 517 518 519 521 522 9 10 11 2 0.11** 0.00 0.04** 0.23** 0.04** 0.31** 2 0.48** 2 0.28** 20.07** 20.15** 2 0.03** 0.13** 0.05** 0.09** 2 0.11** 2 0.01 0.01 20.12** 20.10** 2 0.03** 2 0.19** 2 0.10** 0.00 20.02* 20.03** 0.02* 0.00 0.05** 0.00 0.09** 0.19** 0.17** 2 0.12** 0.22** 20.07** 0.03** 2 0.11** 0.34** 0.30** 0.26** 2 0.25** 0.26** 20.06** 0.05** 0.18** 2 0.07** 0.29** 0.32** 0.28** 2 0.25** 0.31** 20.09** 0.05** 0.74** 0.79** 5 497 Notes: *p , .05, **p , .01, N ranges from 9,277 to 10,072. 513 4 496 Voluntary turnover 0.04 0.20 Gender 0.61 0.49 0.04** Higher education 0.29 0.46 0.02 Age 38.87 10.01 2 0.13** Income 1.01 0.47 2 0.06** Unemployment 8.78 4.51 2 0.04** Job satisfaction 4.36 1.14 2 0.05** Job search behaviour 0.08 0.27 0.15** Absenteeism 0.91 3.66 2 0.01 Embeddedness community 1.88 0.68 2 0.07** Embeddedness organization 1.46 0.74 2 0.08** Job embeddedness 3.34 1.09 2 0.10** 516 3 493 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 520 2 494 495 1 492 SD 491 M Table 2. Means, standard deviations and correlations. RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1563 RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1564 540 541 542 543 544 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 C. Tanova and B.C. Holtom Hypothesis 2 asserts that desirability and ease of movement factors along with behavioural intentions will predict variance in turnover beyond that predicted by personal characteristics. The results of the Cox Proportional Hazards Regression can be seen in Table 3 and Table 4. In the first model, gender, age and income were entered into the equation of the hazard function. From the exponentiated coefficients we can see age reduces the likelihood of changing jobs. The exponentiated coefficient of 0.91 tells us that each increment increase in age (measured in years in our study) will reduce the likelihood of turnover decision by 9% when all gender and income variables are controlled. From Table 4 we can see that the situation is similar in the four countries. When the role of gender is investigated we see that men are 82% more likely to leave their jobs compared to women. However, in the four countries we see that the figure gets as high as 161% more likely in Italy, and 135% more likely in Spain. As we expected, income had an exponentiated coefficient below one. This indicates as the income increases, there is a decrease in the likelihood of voluntary turnover. In model two we entered the desirability and ease of movement variables together with withdrawal behaviours. There was a statistically significant change in model chi square. And among the new variables entered, job search behaviour had an impressive 3.36 exponentiated coefficient which would translate into 236% increase in turnover likelihood if the person was looking for other employment. Higher education also increased the likelihood of turnover, while job satisfaction and the unemployment rate reduced it. The results indicate that self reported absenteeism does not reliably predict turnover in this sample. Hypothesis 3 states that job embeddedness will improve the prediction of turnover beyond that predicted by variables representing personal characteristics, desirability and ease of movement, and withdrawal behaviours. In Tables 3 and 4 we can see that in model 3 job embeddedness is introduced into the model. In the overall model the chi square change is 51.78 and is significant at p , .001. After the effect of all the previous variables are controlled, job embeddedness explains a significant amount of variance in actual turnover. The exponentiated coefficient for community embeddedness is 0.84 which means that an increment in job embeddedness will bring 16% decrement in actual turnover and the organizational embeddedness has an exponentiated coefficient of 0.55 which means that it reduces the actual turnover likelihood by 45%. 570 571 572 573 Table 3. Exponentiated coefficients from proportional hazards regressions of voluntary turnover for the total sample. 574 575 576 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 Gender Age Income Higher education Unemployment Job Satisfaction Job search behaviour Absenteeism Embeddedness community Embeddedness organization Chi-square Change in Chi-square 1 2 1.822*** 0.906*** 0.373*** 1.578*** 0.907*** 0.431*** 1.279* 0.972 0.926 3.355*** 0.989 389.44028*** 605.33546*** 110.424*** 3 1.278 0.919*** 0.520*** 1.616*** 0.950** 1.011 3.443*** 0.996 0.835* 0.548*** 678.04715*** 51.781*** Notes: Values exceeding 1 for exponentiated regression coefficients (eb) indicate a positive effect on turnover risk as the variable increases, while values below 1 indicate a negative effect as the variable decreases; ***P , 0.001; **P , 0.01; *P , 0.05; N ¼ 8,952. 603 604 605 606 607 608 609 610 611 612 613 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 622 623 624 625 626 627 628 629 630 631 632 633 634 635 636 637 2,849 125.355*** 182.499*** 37.152*** 255.430*** 68.767*** 1.193 0.943*** 0.757 1.333 0.951 0.900 2.014** 0.938 0.677** 0.297*** b 1,797 97.900*** Finland 2.017** 0.896*** 0.317*** 2.003 0.915*** 0.541** 0.829 0.990 0.786*** 2.257*** 0.930 Spain 2.347*** 0.912*** 0.484*** 165.551*** 33.755*** 1.894* 0.906*** 0.299*** 1.074 0.989 0.956 4.422*** 0.979 159.624*** 27.989*** 1.322 0.913*** 0.287** 2.415* 0.900 0.928 3.564*** 1.004 0.991 0.502** 188.396*** 12.082** 1.685 0.921*** 0.373** 0.967 0.928 1.037 4.567*** 0.985 0.635** 0.569* 169.457*** 7.563* 3 The International Journal of Human Resource Management 594 595 600 601 Notes: *P , 0.05 **P , 0.01 ***P , 0.001; Values exceeding 1 for exponentiated regression coefficients (e ) indicate a positive effect on turnover risk as the variable increases, while values below 1 indicate a negative effect as the variable increases. Chi-square Change in Chi-square N ¼ Gender Age Income Higher education Unemployment Job Satisfaction Job search behavior Absenteeism Embeddedness community Embeddedness organization 2,667 1,571 90.132*** 602 176.562*** 16.693*** 598 1.913 0.904*** 0.228*** 2.441* 0.950 0.884 3.798*** 1.001 597 Italy 2.615** 0.906*** 0.169*** 596 151.350*** 25.108*** 1.056 0.896*** 0.645 1.544 0.944 0.856 2.696*** 0.997 0.780 0.466*** 2 591 110.251*** 1.264 0.888*** 0.463* 1.363 1.017 0.834 2.923*** 0.994 1 590 Chi-square Change in Chi-square N ¼ Denmark 1.295 0.888*** 0.406* 3 589 Gender Age Income Higher education Unemployment Job Satisfaction Job search behaviour Absenteeism Embeddedness community Embeddedness organization 2 599 1 592 593 Model Table 4. Exponentiated coefficients from proportional hazards regressions of voluntary turnover for 4 countries. RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1565 RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1566 638 639 640 641 642 643 644 645 646 647 648 C. Tanova and B.C. Holtom Discussion The results of this study demonstrate the continuing utility of March and Simon’s (1958) model of turnover, where desirability and ease of movement are regarded as important predictors of turnover. Importantly, however, a new theory of voluntary turnover – job embeddedness – also plays a key role in predicting turnover even after extensive controls. This indicates that the turnover decision is not only influenced by the individual’s attitudes towards work or about the actual opportunities in the labour market, but also influenced by a number of interrelated connections both on and off the job. Moreover, these results point to the generalizability of the construct. Notwithstanding differences in labour laws, cultural factors and unemployment rates between Europe and the US, job embeddedness appears to predict turnover effectively on both continents – at least in the four different countries where it was possible to conduct a rigorous test. 649 650 651 652 653 654 655 656 657 658 659 660 661 662 663 664 665 666 667 668 669 670 671 672 673 674 675 Practical implications The application of job embeddedness has important ramifications for line managers. Leaders in European organizations who are worried about losing their most valuable employees should not only study external pay equity or the job satisfaction of their employees, but they should also try to identify viable methods for helping employees become embedded in the organization and the community. For example, the managers could establish mentoring programmes to strengthen the links employees have with others in the organization. Or managers might encourage work groups to take a prominent role in deciding who to hire into the work group. To strengthen the links with the community, organizations can support community outreach programmes to give their employees opportunities to volunteer and become more integrated into their communities. To strengthen the fit between the individual and the organization, employers need to be thoughtful in the recruitment and selection of their employees. They need to provide realistic information to the candidates before employment and subsequently, employers need to assist their employees in planning their careers. To strengthen the fit between the individual and the community, the employers can provide information about community events or amenities. Employers should also consider locating plants or offices near housing sectors that offer affordable dwellings for employees. Finally, organizations are encouraged to offer unique benefits that are hard for other companies to replicate. Family-friendly hours or benefits provide strong incentives for workers with children to stay for the long term. Allowing individuals to customize their workspace creates a sense of home or familiarity that might be hard to find in other companies. Sacrifice incurred by potentially leaving the community can be systematically increased by providing credit counselling, help finding real estate agents, and partnerships with non-profits that help employees navigate the home-buying process. 676 677 678 679 680 681 682 683 684 685 686 Strengths and limitations There are a number of strengths to this article. One important factor that differentiates this study from others is the use of actual turnover data rather than turnover intentions. Even though there are theoretical arguments and empirical evidence that turnover intentions are very good predictors of actual turnover (Ajzen 2002; van Breukelen et al. 2004), these studies ignore the employees who do not plan to leave the company but do leave because of internal or external events (Lee, Mitchell, Holtom, Hill, and McDaniel 1999; Morrell et al. 2004a). A second strength is the use of a large-scale, multi-country, longitudinal data set where Time 1 variables were used to predict turnover at Time 2. RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 The International Journal of Human Resource Management 687 688 689 690 691 692 693 694 695 696 1567 At the same time, there are limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the data set was not specifically designed to test the theory of job embeddedness. The items chosen exhibit face validity for each of the six sub-dimensions and predictive validity in terms of both job search behaviour and actual turnover. However, it is possible that the items have not fully captured the construct domain. A second limitation is the lack of greater geographic or cultural representation of the diverse European countries. Unfortunately, complete data was only available for the four countries studied. Nevertheless, we believe that this study makes an important contribution to understanding about voluntary turnover in the European Union. Further, when combined with other studies (e.g., Mallol et al. forthcoming), it points to the generalizability of job embeddedness theory. 697 698 699 700 701 702 Acknowledgements The present research was funded by the European Commission under the 6th Framework Programme’s Research Infrastructures Action (Transnational Access contract RITA 026040) hosted by IRISS-C/I at CEPS/INSTEAD, Differdange (Luxembourg). 703 704 References Ajzen, I. (2002), ‘Residual Effects of Past on Later Behavior, Habituation and Reasoned Action Perspectives,’ Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 2, 107– 122. Armknecht, P.A., and Early, J.F. (1972), ‘Quit in Manufacturing, a Study of Their Causes,’ Monthly Labor Review, 95, 11, 31 – 37. 708 Cohen, A. (1993), ‘Organizational Commitment and Turnover: A Meta-analysis,’ Academy of Management 709 Journal, 36, 1140– 1157. 710 Cotton, J.L., and Tuttle, J.M. (1986), ‘Employee Turnover, A Meta-analysis and Review with Implications for Research,’ Academy of Management Review, 11, 55 – 70. 711 Davia, M.A. (2005), ‘Job Mobility and Wage Mobility at the Beginning of the Working Career, a 712 Comparative View across Europe,’ Working Papers of the Institute for Social and Economic Research, 713 no. 2005– 03, Colchester, University of Essex. 714 Fahr, R., and Schneider, H. (2004), ‘Comparison Study of Job Turnover and Job Search Methods between 715 Japan and Europe,’ Report Prepared for RIETI, Tokyo, 30 July 2004. 716 Q5 Fuller, T. (2002), ‘EU Seeks a Cross-border Labor Market,’ International Herald Tribune. Granovetter, M. (1985), ‘Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness,’ 717 The American Journal of Sociology, 91, 3, 481– 510. 718 Griffeth, R.W., Hom, P.W., and Gaertner, S. (2000), ‘A Meta-analysis of Antecedents and Correlates of 719 Employee Turnover, Update, Moderator Tests, and Research Implications for the Next Millennium,’ 720 Journal of Management, 26, 3, 463– 488. Heise, D.R. (1975), ‘Employing Nominal Variables, Induced Variables, and Block Variables in Path 721 Analysis,’ Sociological Methods & Research, 1, 147– 173. 722 Holtom, B.C., Mitchell, T.R., and Lee, T.W. (forthcoming), ‘Increasing Human and Social Capital by 723 Applying Job Embeddedness Theory,’ Organizational Dynamics. 724 Hom, P.W., and Griffeth, R.W. (1995), Employee Turnover, Cincinnati, OH: South-Western. 725 Hom, P.W., and Kinicki, A.J. (2001), ‘Towards a Greater Understanding of How Dissatisfaction Drives Employee Turnover,’ Academy of Management Journal, 44, 5, 975– 987. 726 Hosmer, D.W., and Lemeshow, S. (1999), Applied Survival Analysis, Regression Modeling of Time to 727 Event Data, New York: Wiley. 728 Hulin, C.L. (1991), ‘Adaptation, Persistence and Commitment in Organizations,’ in Handbook of Industrial 729 and Organizational Psychology (2nd ed.), eds. H.C. Triandis, M.D. Dunnette, and L.M. Hough, 730 Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, pp. 445– 507. Jovanovic, B. (1979), ‘Job Matching and the Theory of Turnover,’ The Journal of Political Economy, 731 87, 5, 972– 990. 732 Law, K.S., Wong, C., and Mobley, W.H. (1998), ‘Toward a Taxonomy of multidimensional Constructs,’ 733 Academy of Management Review, 23, 741– 755. 734 Lee, T.W., and Mitchell, T.R. (1994), ‘An Alternative Approach: The Unfolding Model of Voluntary 735 Employee Turnover,’ Academy of Management Review, 19, 51 – 89. 705 706 707 RIJH 329649—8/8/2008—MADHAVANS—305665———Style 2 1568 736 737 738 739 740 741 742 743 744 745 746 747 748 749 750 751 752 753 754 755 756 757 758 759 760 761 762 763 764 765 766 767 768 769 770 771 772 773 774 775 776 777 778 779 780 781 782 783 784 C. Tanova and B.C. Holtom Lee, T.W., Mitchell, T.R., Holtom, B.C., Hill, J.W., and McDaniel, L. (1999), ‘Theoretical Development and Extension of the Unfolding Model of Voluntary Turnover,’ Academy of Management Journal, 42, 450– 462. MacCallum, R.C., and Browne, M.W. (1993), ‘The Use of Causal Indicators in Covariance Structure Models: Some Practical Issues,’ Psychological Bulletin, 114, 533– 541. Mallol, C., Holtom, B., and Lee, T. (forthcoming), ‘Job Embeddedness in a Culturally Diverse Environment,’ Journal of Business & Psychology. Mano-Negrin, R., and Tzafrir, S.S. (2004), ‘Job Search Modes and Turnover,’ Career Development International, 9, 5, 442– 458. March, J.G., and Simon, H.A. (1958), Organizations, New York: Wiley. Mitchell, T.R., Holtom, B.C., Lee, T.W., Sablynski, C.J., and Erez, M. (2001), ‘Why People Stay, Using Job Embeddedness to Predict Voluntary Turnover,’ Academy of Management Journal, 44, 6, 1102– 1122. Morrell, K., Loan-Clarke, J., and Wilkinson, A. (2001), ‘Unweaving Leaving: The Use of Models in the Management of Turnover,’ International Journal of Management Reviews, 3, 3, 219– 244. Morrell, K., Loan-Clarke, J., and Wilkinson, A. (2004a), ‘The Role of Shocks in Employee Turnover,’ British Journal of Management, 15, 335– 349. Morrell, K., Loan-Clarke, J., and Wilkinson, A. (2004b), ‘Organisational Change and Employee Turnover,’ Personnel Review, 33, 2, 161– 173. Peracchi, F. (2002), ‘The European Community Household Panel: A Review,’ Empirical Economics, 27, 1, 63 – 90. Royalty, A.B. (1998), ‘Job-to-Job and Job-to-Nonemployment: Turnover by Gender and Education Level,’ Journal of Labor Economics, 16, 2, 392– 443. Sablynski, C., Mitchell, T., Lee, T., Burton, J., and Holtom, B. (2002), ‘Turnover: An Integration of Lee and Mitchell’s Unfolding Model and Job Embeddedness Construct and Hulin’s Withdrawal Construct,’ Psychology of Work, 189–203. Shaw, J.D., Delery, J.E., Jenkins, G.D., and Gupta, N. (1998), ‘An Organization-level Analysis of Voluntary and Involuntary Turnover,’ Academy of Management Review, 41, 5, 511– 525. Trevor, C. (2001), ‘Interactive Effects among Actual Ease of Movement Determinants and Job Satisfaction in the Prediction of Voluntary Turnover,’ Academy of Management Journal, 44, 4, 621– 638. van Breukelen, W., van der Vlist, R., and Steensma, H. (2004), ‘Voluntary Employee Turnover: Combining Variables for the Traditional Turnover Literature with the Theory of Planned Behavior,’ Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 893– 914.