Examination report plus observations 2004 - pdf

advertisement

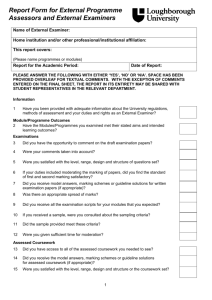

GENERAL DENTAL COUNCIL VISITATION OF FINAL BDS EXAMINATION OF BIRMINGHAM SCHOOL OF DENTISTRY UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM 7 AND 8 JUNE 2004 REPORT OF THE VISITORS PROFESSOR M L JONES BDS MSC PHD DORTH FDSRCS MR D G SMITH BDS LDSRCS DGDP (UK) DPDS FOREWORD Purpose 1 As part of its duty to protect patients and promote high standards, the General Dental Council (GDC) monitors the education of dental students in the UK’s dental schools. The aim is to ensure that dental schools provide high-quality learning opportunities and experiences and that students who attain a dental degree are safe to practise. GDC process 2 In a six-yearly cycle the GDC appoints a team to visit each dental school. Each team includes dentists and lay people. The visitors report to the Council on whether the University's programme and examinations meet the recommendations in the GDC's The First Five Years: A Framework for Undergraduate Dental Education (2nd edition). 3 This report sets out the findings of the two-day visit to the Birmingham Dental School’s BDS Final Examinations using the assessment principles and guidelines set out in The First Five Years (paragraphs 122-128) as a benchmark, and the headings from the ‘General Report of the 1999/2000 Visitation of Examinations’ as a structure. It highlights the many areas of good practice but also draws attention to areas where issues of improvement and development need to be addressed. The report is based on the findings of the visit and on a consideration of supporting documents prepared by the School, including a self-evaluation document. The visitors also considered the previous report and recommendations of the GDC visitation to the Final Examination on 8 December 1999 and 5 and 6 June 2000. 4 The University will be given the opportunity to correct any factual errors in this report and then submit its observations. The report and response will then be considered by the GDC. 5 Prior to the Visitation of the Final Examinations at Birmingham Dental School, five visitors (including the two who returned to observe the Final Examination) made a three-day visit to the BDS programme. After the report on the Final Examination visit has been made, the whole team of five visitors will make a recommendation to the Council on whether the programme and examination are ‘sufficient’ (the term used in the Dentists Act) for the protection of patients. 6 After the reports of the programme and Final Examination visits to Birmingham Dental School have received formal approval from the GDC they will be published on the GDC website and presented to the Privy Council. The visitors' recommendations will be followed up through a formal monitoring process. A General Report will also be published when all dental schools have been visited. This will outline general trends and make overall recommendations for good practice and improvement. 1 Acknowledgements 7 The visits to the Final BDS Examinations at Birmingham Dental School took place on 7 and 8 June 2004. We were welcomed by Professor P M Marquis, the Director and Head of the Dental School and Professor P Lumley, the Deputy Director of the School who has a leadership role for Learning and Teaching. We wish to thank Professors Marquis and Lumley and all concerned with the Final BDS Examinations in Birmingham for their help, hospitality and courtesy during our visit. A separate, private room was made available to us throughout our visit and this, together with the other physical arrangements made for us, helped considerably to facilitate our work. We also appreciate the high standard of documentation provided by the School. Policy for disabled and dyslexic students 8 The University has a number of provisions in relation to students with disabilities, including those with dyslexia. These are readily available to students. The Student Support and Counselling Service co-ordinates services for students with disabilities in terms of admissions to courses and providing on-going support to enable students to study effectively and make full use of opportunities at the University. The published guidelines ‘Extra Time in Examinations for Students with Dyslexia or Dyspraxia’ indicate the type of special arrangement that will be considered. FINAL EXAMINATION Overall structure 9 There are three basic elements to the Final BDS Examination: • • • The written section The Clinical Dentistry section, incorporating Speciality Teaching areas & Clinical Practice Continuous Assessment Grades and the Case Presentation (Seen Case) The Patient History, Examination, Special tests and Treatment Planning section (Unseen Case) 61 candidates sat the 2004 Final BDS Examination. All of the candidates passed, six with distinction and one with honours. In-course assessment 10 The visitors were grateful for the opportunity to see documentation on the role of coursework and, in particular, in-course assessment in all dental degree examinations. There was also the opportunity to question the Head of School and Deputy Director about the whole area of this form of assessment and its contribution to the marks awarded in the Finals Examination. 11 It was clear from the documentation supplied to us, together with our observations, that in-course assessment marks form an important component of the total mark in 2 the clinical parts of the Final BDS Examination. Favourable in-course assessment does not allow exemption from any component of the Final Examination, whilst poor in-course assessment performance does not appear to prevent any student from sitting the Final BDS Examination. However, it can, and does, have a role in ‘filtering’ students in the earlier years. This was particularly true in the fourth year where examples were given to us of students either repeating the year or changing their course, based on the outcome of the continuous assessment. 12 External examiners are invited to observe the continuous assessment process but are not involved in developing or validating the detailed in-course marks. However, one external examiner does attend a meeting prior to finals where the various assessment marks are drawn together into an overall mark and thus an intention grade (A-E) in the defined areas of ‘Specialty Teaching’ and ‘Clinical Practice’. We had the opportunity to discuss this with the External Examiner concerned who was content with his input to this process. “Signing-up” procedure 13 The essence of the signing-up procedure is based on a satisfactory quantitative record of the student’s clinical experience and appears not to be qualitative by any formal mechanism. However, where poor performance is recognised through the comprehensive, continuous assessment records from years three and four of the course, there is a procedure by which students may be counselled formally (and informally) and, on occasion, may not be allowed to progress into their final year. They may be required to repeat part of the course or may make a change of direction into a more appropriate university course. 14 External examiners are not involved in the formal ‘signing up’ for finals procedure at Birmingham. In-course assessment is not used formally to assess the amount of clinical work completed to a satisfactory standard which might then allow a student to proceed to Finals. However, documentation would suggest that certain specific specialty assessments must be satisfactorily completed to proceed to the Finals Examination. The various specialty assessments did not appear to conform to a standard model of content, type and timing. External examiners do not participate in these procedures, although they would be involved in any internal assessment or examination which could lead to a student being excluded from the dental undergraduate course. Written examinations 15 There are two papers which comprise the written section of the Final BDS Examination. Fourteen specialty/topic areas have been identified to be examined. Paper 1 has four mixed essay questions from eight of the ‘specialty/topic’ areas, selected by an appropriate randomised process. Paper 2 comprises ten short answer questions, six of which are the residual topics from those not selected on Paper 1; the other four are then made up by randomly selecting them from the whole fourteen topics by a similar randomised method to that described above. The Heads of the various specialty areas are then asked for the nomination of internal examiners to set appropriate questions and prepare ‘model’ answers. They will also be involved in arranging the double marking of the scripts. Before the questions are proofed to the papers they are checked by a small internal 3 examination panel to confirm that they are appropriate both in terms of the phrasing of the question and the mix of topics covered on the paper. This is done taking account of external examiners’ comments by maintaining a dialogue during the process. Finally, the external examiners are asked again for their opinion before the composite papers go off for printing. The question papers for the 2004 examination were judged by the visitors to be satisfactory. 16 Looking back over the past papers supplied for inspection, the visitors could not see any obvious omissions in terms of major curriculum topics although it was noted that the area of dental team-working might have been better covered. 17 There is a very clear guide to the examiners in terms of model answers and the appropriate marking regime. In addition, there was a very robust method in place to preserve the anonymity of the candidate on the written papers right up to the development of the final grid of marks and just before the final examiners’ pass/fail meeting. 18 With regard to the scripts, all are double blind marked with a documented process to resolve disagreements in the mark where appropriate, although this did not appear to work as robustly as intended. 19 All papers were seen by external examiners to confirm that the mark was appropriate. Although each external examiner did not see every script we were assured that they were given an appropriate range of performance. At a meeting at the end of the first day of the examination, chaired by the Head of School (the Dean), all written marks were agreed with an internal representative from those responsible for each question present. At this meeting the percentage marks for each question were collated into an overall mark for each paper and then into an overall rounded percentage which was subsequently translated into an intention grade (A-E). It was noted that on two occasions external examiners recommended a candidate should receive a small raise in marks to be awarded an A grade overall for the paper. Such a raise may well have been appropriate. However, one of the more experienced internal examiners appeared not to be familiar with the process. Another internal examiner drew attention to one question in one of the papers which had been failed by a significant number of candidates. The committee was assured, by the Chair, that there was a process to review this subsequently. 20 The effect of averaging ‘average’ percentages to obtain a final overall mark and then an intention grade was to greatly reduce the range of marks of the candidates in this section of the examination. Prior to the ‘raising’ of two candidates, as already mentioned, the grid of marks demonstrated that 97% of candidates fell into grades B & C with no A or E grades awarded. 21 Of serious concern were discrepancies, noted by the visitors, in the reconciliation of written paper marks. In fairness to the internal examiners the documentation guiding this process did appear to be contradictory. The documents concerned are the ‘School of Dentistry BDS Assessment Guidelines and Procedures for the Conduct of Examinations’ (Paragraph B2 -dated Jan 2003) and the ‘Guidelines for Setting Questions for Final BDS Paper 1 – Marking Scheme’ (adopted by the Curriculum Development Committee 2001). 4 22 In the event, two pairs of examiners had failed to apply consistently the rules to agree the mark for each written question. This had some effect on the mark awarded to the papers for a number of candidates which in a limited number of circumstances might have impacted on the grade awarded for the paper (A-E). Apparently, these discrepancies in the internal examiner marking were not spotted in good time by the external examiners. 23 As an example, the current guidance states: ‘where marks differ by 5%, the higher of the two marks shall be recorded. Differentials of 10% will be averaged and that mark recorded. If the differential is greater than 10% or the internal examiners cannot agree the mark then the paper will be remarked. The external examiner shall resolve any remaining differences of opinion’. 24 Inconsistencies observed by the visitors included: • Failure to record the higher of two marks 5% apart • Failure of examiners to mark at 5% intervals • Where differences in marks were between 5% and 10% there was no consistency in rounding up or down. External examiners had made no comments on these inconsistencies. Clinical examinations 25 The visitors had the opportunity to be present for the clinical examination of both the ‘seen’ presentation case (treated previously by the student) and ‘unseen’ case (new patient for clinical history and examination). Seen case - Presentation of treated patient 26 In the Presentation of Cases (seen) part of the examination the students were allowed five minutes to present a patient for whom they had provided dental care. There followed a ten minute oral examination by the examiners. This appeared to be sufficient time where it was used efficiently by the examiners in a pre-planned manner. 27 There were three examiners in each team, of whom one was an external, one was an internal teacher from Primary Care and one was an internal member of the academic staff of the school. The majority of the examiners were considerably experienced with most, although not all, having had some formal training in assessment procedures. 28 The patients, as presented by the students, appeared to be of a generally good standard with a fair spread of treatment performed including different types of restoration, crowns and bridges, management of periodontal problems, implementation of preventive regimes. A number of patients appeared to have had significant early management problems (for example anxiety and communication issues), although there was little questioning in this area, perhaps due to the presence of the patient during the examination. The students consistently presented excellent poster boards and appeared generally to have prepared good oral presentations of their work. Having said that, there were isolated examples where radiographs and hospital notes were not immediately available to the 5 examiners, and another where the patient had not been properly prepared for examination (no safety spectacles fitted). 29 A good innovation in this section of the examination was the summary sheets on each patient prepared ahead of time by the students. They would have been of even greater use to the examiners (especially the external examiners) if they had been available in advance of the examination day to assist in formulating lines of questioning. There were clear information sheets on the conduct of the examination and guidelines for marking given to all examiners at a meeting which was held prior to this section of the examination and chaired by the Deputy Director of the School. This thirty minute meeting also gave the opportunity for a full briefing and the chance to deal with any questions from the external examiners. 30 However, there appeared to be no clear format given as to how this examination should be conducted ‘on the ground’. As an example, one group of examiners had discussed beforehand who did what: one to listen to the presentation, one to examine the patient and one to question the candidate. They then rotated the tasks for each candidate examination and adhered to the clear timing allocations. Some groups of examiners had not decided who should do what with, on occasions, one examiner (not always the external) dominating the proceedings and another, an internal examiner, practically a non-participant, asking no questions. 31 In best practice the examiners used the excellent mark sheet to give a grade for ‘planning & understanding’ and ‘practical standards’ (A – E) separately. They then came together after this initial process to have a discussion on the student’s performance, usually led by the external. They then agreed the overall mark. This seemed very logical and a good approach. However, on other occasions there was no separate marking, just a broad-based discussion sometimes dominated by one examiner who could be either external or internal. 32 The clinic facilities for this part of the examination were generally adequate although, in some cases, there was only a limited private facility to which the examiners could withdraw to discuss the student’s performance and confirm the mark. At times there was some unnecessary extraneous noise from nonparticipants in the examination, although this did not appear to have distracted the candidates. 33 All of the patients presented, who had been selected by the students, were adult patients who had had restorative care and a minority of other specialty care (e.g. Oral Surgery). There were no child patients presented. This may have limited or made the role of the external examiner ‘lead’ difficult where they were not from a restorative background. The visitors noted that, in the sample of the cases seen by them, a number of the patients had not completed their planned courses of treatment. This was less than satisfactory and not in accordance with the spirit of the examination regulations. We appreciate that many students may have been unable to present their first choice patient, or even their second or third choice, because of patient inability to attend. If this is a common problem, then perhaps the method of examination needs to be re-thought. 34 At the examiners meeting where the marks were considered 6 out of 61 students sitting the exam received a D grade and some had quite serious comments from 6 the external examiners, including: active caries present; inappropriate radiographs having been taken; poor partial denture design; inappropriate restorations; missed veneers on examination; poor understanding of bone loss; missed gingivitis and presenting the wrong study models for the patient. There would appear to be some issues of quality control in the treatments being performed and presented. Subsequently, all of these D grades were compensated by the Continuous Assessment Component to give an overall Clinical Dentistry Section Grade. Unseen case – History & examination of a patient 35 In this section of the Finals Examination a student examines a patient for 30 minutes and then presents the history, the results of the examination, and other findings to three examiners. This process takes 15 minutes and is to a similar format as previously described in the ‘seen’ area of the exam. There is always an external examiner present and involved in this oral examination. The format for the exam is very clear, as are the instructions for the intention marking scheme (A-E). These are given in written form prior to the examination and before the briefing session, which ran in a similar manner to the previous day. The guide to marking was always available to the examiners and it was pleasing to see that they regularly referred to it when deciding the appropriate grade. 36 In this unseen part of finals the opportunity to fail a student, and thus Final BDS, by the award of an ‘E’ grade is retained but all examiners are familiar with the consequences of recording such a grade and the need for good supporting written evidence to justify such a grade. External examiners were also expected to keep a record of reasons when a ‘D’ grade was given, another good practice. 37 The organisation for this part of the exam was superb and broadly ran to time. All examiners were given adequate time to examine the patients prior to each block of oral exams. There were excellent briefing sheets given to the examiners with information on each patient to be clinically examined by the candidates. No patient was seen by more that two students in the exam, which removed the opportunity for any collusion between students. 38 The types of patients seen were as follows: approximately 25% Oral Medicine; 20% Orthodontics/Paediatric Dentistry and the remainder were predominantly adult Restorative Dentistry or multidisciplinary cases. 39 There were a variety of approaches taken by the examiners in this section of the exam. Perhaps the best practice we saw was where one of the internal examiners acted as the team leader. They made sure that patients were properly examined by the examiners; lines of questioning were decided in advance for each of the three examiners and they made sure that the external examiner was fully engaged in the whole process. They introduced the candidates to all of the examiners at the start of the oral examination and then handed over to the ‘external’. They decided time allocation (for example 5 – 5 – 5 minutes) and then kept to that time allocation and made sure that the viva was concluded on time. Another effective variation was where two examiners questioned, whilst one kept notes and provided feedback at the discussion of the mark to be awarded. Where things worked less well, the division of labour between the examiners had not been decided in advance and thus one personality might dominate proceedings. In one of the 7 groups there was consistent over running of the questioning time after the bell had sounded. This was observed by both visitors. In the event, we felt that all candidates we saw had been fairly examined in the unseen section of the examination and that the marks given were appropriate. 40 However, there was one exception to this, which worried both visitors and which relates to the inevitable lack of anonymity in this part of the examination. After one oral examination there was a definite disagreement between one internal and one external examiner with the remaining examiner more ambivalent. This was observed by one of the visitors. The disagreement was over the award of either an ‘A’ or a ‘B’ grade. This disagreement was unresolved in the examination and came all the way to the examiners’ meeting, with the external presenting his view on the award of a ‘B’ grade. In such a situation the unbiased view of the external should be particularly influential, especially since he had no prior knowledge of the candidate. Oral examinations 41 The classic viva voce examination is not a formal part of Final BDS Examination in Birmingham except in the case of students being considered for the Dentsply Prize. We were told that the regulations of the University of Birmingham no longer allow Pass/Fail vivas to be held. 42 Obviously, there still remains some component of a classic ‘oral’ examination in the ‘seen’ and ‘unseen’ parts of finals and this is entirely appropriate. 43 When it came to the Prize viva the same rules for selection of the examining team are applied as previous, with one external examiner being included in this team. The external examiner played a lead role in the oral exam. 44 The accommodation for this viva was appropriate. There was no clear scheme of marking since it was not required. The best out of the five students was simply awarded the prize after a broad ranging viva; one of the other candidates also received a certificate of commendation. These arrangements all appeared to work satisfactorily. Compensation across elements of the examination 45 An ‘E’ grade awarded in any component can result in a Fail in Final BDS, as will two ‘D’ grades in any two of the components. These cannot be compensated. Otherwise there is compensation between the sections and within the first two sections. 46 It was noted by the visitors that in the written section the effect of the system applied for reconciling marks may be such that some candidates may not have been adequately rewarded for their excellence whilst other with a poorer performance may have been less easy to identify. 47 However, the visitors noted that the recommendations made in the 2000 GDC report with regard to mitigation for an ‘E’ grade in one component of the clinical sections had been addressed in the Presentation Case (seen component). 8 Honours and Distinctions 48 The School has robust regulations on the award of honours. The system is based on honours points collected during the course with 14 of the total needed to be achieved in the Final BDS Examination. The system appears both fair and reasonable and it was pleasing that this accolade was awarded to two students. In addition a reasonable number of distinctions were awarded in a year where there was a 100% pass rate. It was the second time this had occurred in five years. There was good documentation available on the final marks grid which included data to assist the examiners in the award of Honours, Distinctions and the Gold Medal. Role of the external examiners and determination of results 49 There were a number of formal examiners meetings during the course of the two days of the Final BDS Examination. Appropriate internal examiners, and other members of staff, were present and the External Examiners were always in these meetings. In the moderation process External Examiners were fully engaged and some marks were modified as the result of these discussions. Most modifications were to the benefit of the candidates where they were at the borderline of an intention grade (A-E). 50 The role of the external examiners at the Dental School in Birmingham appeared to largely conform to the assessment guidelines in TFFY (Paragraph 127). 51 The overall result was that all students sitting the examination passed. There were six distinctions in Clinical Dentistry and one pass with Honours, this person also receiving the Carlton Gold Medal for the best performance. 52 The students were informed immediately after the meeting of the examiners concluded with the posting of the pass list. There appeared to be good supportive arrangements in place to support and advise candidates that fail, although there was no need on this diet of the examination. In the diet we observed there was excellent help and support for one student who suffered a ‘panic attack’ before the final unseen case. The timing of the examination was adjusted and the student gave an adequate performance to pass. Arrangements for failed candidates 53 In the event of a student failing it is currently not possible to carry any partial success forward to the resit which usually is timed to occur 5 months later in November. In the intervening months failed candidates are counselled, weaknesses identified and an appropriate further education and training programme put in place. The visitors were told that most usually the problems could be largely addressed through further work in the Primary Care area. Appeals 9 54 Appeals are directed through the University’s central appeals process. Appeal is only possible against procedures, not against results or the judgement of examiners. External examiners’ reports 55 The visitors had the opportunity to review the External Examiners’ reports for the entire undergraduate programme for the last three academic years. These appeared to be satisfactory and where issues had been raised there existed an effective mechanism for considering these matters within the school and then responding. There was also a methodology across the Faculty for considering similar reports to the different schools. The visitors had a brief opportunity to meet with the five external examiners involved in this diet of Final Examinations and they were able to reassure us and give examples of actions resulting from External Examiner reports. Training and guidance for new examiners 56 New examiners undertake an induction process, part of which includes observing a Final Examination. Good quality induction packs were sent to new examiners prior to the Final Examinations. These packs set out the aims, structure, process and grade outputs expected in the examination. There was also a good guide to assessment. GENERAL COMMENTS We would like to draw attention to the following comments resulting from our visit to the BDS Final Examinations: 57 In general the documentation to support the Final Examinations was excellent. Indeed, most of the documentation we were able to view for the examinations processes associated with the BDS course were of a good standard. 58 The administrative support for the Finals Examination appeared to be excellent and all documentation requested was produced in a timely manner. 59 The whole process of written question setting was excellent and there was a robust arrangement for keeping external examiners involved during the formulation of Papers 1 and 2. In general there appeared to be good coverage of the key topics in the written papers. 60 The principle of including in-course assessment towards the final mark in the Final BDS Examination was a good practice and the attempt to involve the external examiner in this process is to be commended. 61 The selection of cases for the unseen presentation worked well and the students were exposed to a good range of problems. There was a process in place to make sure no patient was used more than twice for this part of the examination. The clinical arrangements for this part of the examination worked well. 10 62 The induction process for both internal and external examiners was good as were the briefing sessions prior to each section of the examination. 63 The written descriptors of the grading system were good and appeared to be regularly used by the examiners when determining the A –E grade to be awarded, especially in the unseen component of the examination. 64 In the Presentation (seen case) component of the examination there were some weaknesses detected. Although the majority of the students presented good, well treated cases a significant number presented treatments that were not completed. 65 We noted that 6 of the cases presented had some significant elements of poor management which suggest some concerns about supervision in their preparation. 66 During the Case Presentation section more evident senior management might have addressed some of the minor problems such as marking accommodation, extraneous noise and timing. 67 In the written papers there was a serious problem with the paper marking system and the reconciliation of the double marks. Two pairs of internal examiners appeared not to be properly following the guidance and there was documentary evidence in previous examination minutes that this had happened before. In mitigation there appeared to be some contradictions in the two documents offered for guidance. 68 A problem with the reconciliation system for the written paper marks was that it made it difficult for outstanding or good candidates to be rewarded appropriately in the translation to the intention grade whilst it was also more difficult to identify the weaker students. Essentially, the problem with the system was one of poor discriminatory capacity in the marking resolution scheme. 69 In both the Seen and Unseen presentations to examiners there was not sufficient consistency in running the oral aspects of the examination. One team ran consistently over the allotted time and others had the questioning dominated by one person. A method of how this problem might have been easily corrected was in operation in other groups of examiners and is in the text of the report. 70 Related to the problem of not always having a leader in these oral teams was one disturbing observation of the visitors. A significant disagreement on grade between two examiners occurred in the Unseen examination which should have been resolved before it came to the examiners’ meeting. The external examiner’s view should be particularly influential in these cases. 71 Medicine and Surgery examinations were not double marked, although the practice complied with University guidance. RECOMMENDATIONS 11 The key areas for action identified by the Visitors are summarised below. Additional comments are contained within the body of the report itself. Figures in brackets refer to paragraph numbers in the main body of the report. 1. To the GDC (To be determined after consideration of this report together with that from the programme visitation) 2. To the University • There is an urgent need for clarification of the guidance given for marking in written examinations in order to resolve any potential confusion between examiners [School of Dentistry BDS Assessment Guidelines and Procedures for the Conduct of Examinations (Paragraph B2, dated Jan 2003) and the Guidelines for Setting Questions for Final BDS Paper 1 – Marking Scheme (adopted by the Curriculum Development Committee 2001)]. (21-24, 67-68) 3. To the School • • • • • • The School should ensure that whole examination papers are not duplicated in subsequent diets. (16) The School should explore how it could bring greater clarity and coherence to the documentation dealing with specific assessments which must be satisfactorily completed in order for undergraduates to proceed to the finals exam. (14) The School should urgently review the guidance on marking in the documents ‘School of Dentistry BDS Assessment Guidelines and Procedures for the Conduct of Examinations’ (Paragraph B2 -dated Jan 2003) and the ‘Guidelines for Setting Questions for Final BDS Paper 1 – Marking Scheme’ (adopted by the Curriculum Development Committee 2001). The School should reconcile the apparently contradictory guidance and give unambiguous advice to both internal and external examiners, and quality assure the process. The particular role of external examiners in scrutinising the reconciliation of marks should be emphasised. (21-24, 67-68) The School should re-visit the effect of averaging ‘average’ percentages to obtain a final overall mark and then converting into an intention grade in the Written component of the Final BDS Examination. This greatly reduced the range of marks of the candidates in this section of the examination and meant that discrimination of the very good or poor student was lacking. (20, 68) Very useful summary sheets on each patient in the Case Presentation exam had been prepared ahead of time by the students. The School should consider making these available to examiners in advance of the examination day to assist in formulating lines of questioning. (29) The lack of anonymity between the presentation (seen) case marking and the marking of the unseen case needs to be handled with particular caution. Performance in a previous part of the examination should not be permitted to influence the judgement of examiners, positively or negatively. The School should give guidance that objectivity and strict attention to the interpretation of the published examination criteria is 12 • • • • required, and if there is clear variance between examiners it would be expected that the external examiner’s arbitration or assessment should prevail. (17, 40, 70) The School should give guidance to the examiners on best, or most effective, practice (as identified in the text of this report) in conducting the Case Presentation and Unseen Patient parts of the examination. This it could do either in the examiners’ induction pack, or at the very useful examiners’ briefing meetings, or both. (30, 69) The School should provide senior staff supervision of clinics during the examinations to ensure smooth running and avoid unnecessary, extraneous noise from nonparticipants. There should always be sufficient private areas to which the examiners could withdraw to discuss the students’ performance and confirm the mark. (32, 66) Virtually all of the Case Presentations patients were adults who had had restorative care and a minority of other specialty care (e.g. Oral Surgery). The School should consider how this may influence the participation/role or effectiveness of the external examiner ‘lead’ who is not from a restorative background, and ensure sufficient compensation. (33) A number of comments made by the external examiners about a small number of ‘Seen’ patients presented by students were a cause of concern e.g. active caries present; inappropriate radiographs having been taken; poor partial denture design; etc. There was thus evidence that some patients had been receiving less than satisfactory care. The School should ensure that it is always clear which staff member is responsible for a patient’s overall care. 13 Birmingham Observations - GDC Report on Finals Introduction The University of Birmingham welcomes the constructive and supportive comments contained within the GDC report on the Final Examination. We value feedback and have implemented many of the visitors comments as can be seen in the recommendations section of our observations. We remain concerned however as to the accuracy of two statements made by the GDC visitors as they are based on verbal comments by external examiners that were not reflected in their formal written reports on the examination to The University of Birmingham through the QAA process. These comments relate to patients examined by the externals but not the visitors and we therefore feel the externals are more competent to comment on the two issues raised in sections 34 and 65. The Head of the Dental School has written to the Chief Executive of the GDC separately on this. We have contacted our external examiners in regard to the statements made by the visitors in sections 34 and 65. The following statement, compiled from written comments made by external examiners, is a unanimously agreed joint statement from the five external and all internal examiners (involved in the observed Seen Case examination) and the University of Birmingham. “The external examiners believe the GDC visitors picked up on aspects of these cases and gave them more weight than did the examiners, whose specific comments have been taken out of context, misconstrued and as a result misinterpreted in the report. The comments were never intended to indicate that treatment was inappropriate or inadequate, though some were incomplete. The factors identified by the GDC visitors were discussion points about which the patient centred care was being discussed with the students, with alternative treatment modalities being discussed to explore the students understanding of the cases they presented rather than to imply that the care was seriously deficient or that alternatives would have necessarily been more appropriate”. 34 We feel “serious comments from external examiners” is overstated and that our view is supported by the external examiners statement above. Variations in treatment planning e.g. caries management (which can be quite different in a fluoridated compared to a non fluoridated area) and partial denture design are well recognised and reported in the literature. We do not find it unusual that such differences of opinion may arise. We also feel that the comment relating to bridgework being placed on an unstable Periodontal foundation is incorrect as it relates to mobile abutment teeth with a reduced but healthy periodontal attachment and one that would be compromised by a removable prosthesis. The literature is clear and robust on this issue. Such variations in clinical opinion are common to all practice and examination situations. This however does not preclude students from receiving an unsatisfactory grade, as part of the examination relates to their understanding of what they did/did not do and why, which can demonstrate an unsatisfactory performance. Students are advised to remain with the same member of staff when managing patients. It is the responsibility of the student not the member of staff to maintain continuity and timetables are arranged to facilitate this e.g. students attend final year General Dental Practice clinics on Mondays and Thursdays and staffing is consistent. Students are advised to have “Monday” and “Thursday” patients. 14 Finally on this issue we believe that it is the students who are being examined in the Seen Case and not the supervising member of staff. Cases are not picked, judged or completed by staff. Students are advised, but ultimately make their own decisions regarding patient selection sometimes against advice. Students although advised not to present a particular case by a member of staff may decide to do so. Three out of the six students who received borderline fail grades appear not to have discussed their cases with staff as to suitability. 65 We feel “significant elements of poor management” is overstated and that our view is supported by the external examiners statement above. Please find our observations on the remainder of the report below. 14 We recognise the lack of uniformity of assessment leading to the signing up procedure for final BDS. Each specialty area is asked to ensure that students have demonstrated attainment of the learning outcomes of the TFFY’s and have completed course requirements. The specific nature of these assessments varies according to specialty, but is clearly set out for students in the respective course information. The TFFY’s learning outcomes are themselves diverse and we feel it is inappropriate to use standardised assessment procedures for widely varying specialties with diverse stated learning outcomes. 21-> 23 The confusion over marking schemes relates to the two following extracts from our guidelines. The first is sent with the details for setting final examination questions, the second is a more generic statement in our rules and regulations. Guidance for Finals marking Paper 1 Each internal examiner should mark this paper separately to the nearest 5%. Where a 5% difference is identified in the two marks the higher score shall be used, unless one examiner objects, whereupon the two examiners shall agree an appropriate final mark. A 10% difference will normally result in the two marks being averaged and a difference of 15% or more will result in both examiners having to re-assess and re-mark the paper together. Guidance in Rules and Regulations At least two internal examiners should, where possible, participate in the adjudication of all written examinations. Scripts will be marked independently and an overall mark agreed. Where marks differ by 5% the higher of the two marks shall be recorded. Differentials of 10% will be averaged and that mark recorded. If the differential is greater than 10% or the internal examiners cannot agree the mark then the paper will be remarked. The external examiner shall resolve any remaining differences of opinion. Where double marking is not possible a robust and agreed moderation must be used. We accept that the guidance would have been clearer if 5% was included in the second sentence of the rules and regulations 24 It is correct the external examiners did not notice the inconsistencies, however, the Director of Learning and Teaching, Head of Academic Programmes and School Manager revisited the pairs of marks for all questions in paper 1 for every student, applied the guidance as appropriate and confirmed that no student had been disadvantaged. The visitors were informed of this at the time of the visitation. In future we will include the marking guidance on the mark sheets completed by the examiners and should the guidance not be followed the marking sheets and manuscripts will be returned for re-marking. 15 30-31 Conduct of examinations is important and we will produce guidelines for each examiners role and conduct. However we feel that this may be considered too prescriptive for external examiners. We agree that independent marking before discussion is preferable. 32 The intention had been to use both sides of floor 4 for the Seen Case examination, as was the procedure on the Tuesday for the Unseen Cases. Some essential refurbishment work had however been carried out on 4E during Spring Bank Holiday Week which resulted in extra clinic preparation prior to the examination. We agree using both sides would have resulted in a quieter environment and more space for the examiners. 33 We would like to make the following observations on para 33. The comment “this may have limited or made the role of the external examiner lead difficult if they were not from a restorative background”. All our external examiners are made aware of the need to examine across specialties before they accept the nomination. In addition we are examining undergraduate students at primary care level and all our external examiners hold postgraduate clinical qualifications (FDS or MFDS) in general dentistry. However should the advice of the visitors be that the Seen Case should only involve external examiners from Restorative Dentistry then we will consider it. We are aware that of the six unsatisfactory grades awarded 5 of these were when the external was not from a Restorative Dentistry background. …..One of the two non Restorative Dentistry external examiners applauded our cross specialty approach in their report this year “This cross sectional approach, also used in the clinical examinations, rather than limiting the external examiners just to their clinical specialty areas enables the external examiners to see the overall standards rather than those in a narrower clinical specialty”. A number of the seen cases were not completed and we appreciate this is not ideal. Some students were presenting 4th, 5th or 6th choices or in some instances any patient that could attend. The inability of some patients to attend is what happens in reality and is beyond the control of the student and School. This point also informs other comments in the report 28, 34, 64, 65. 40 48 The comment in regard to “re-thinking the Seen Case part of the examination if inability of patients to attend” is a concern. Firstly part of this problem may be due to the closeness of the examination to the Spring Bank Holiday – clearly we could re-visit the timing. Secondly part of this problem may be due to unsatisfactory student organisation. Finally we used to run the Seen Case internally which allowed greater flexibility in appointments for patients. However we included the Seen Case part of the external examination in response to external examiner comments and the recommendation within TFFY’s that examples of practical work should be seen by external examiners. We understood this to be a requirement of the General Dental Council, however the experiences of staff from our School who have examined in other establishments would suggest not all Schools subject their students to the rigour of this type of examination. We feel that the view of the external was initially allowed greater influence as the examiners felt the candidate was a borderline A/B with the external at the B level. The University and School consider the exam board to be the competent authority and that when there are or were differences, the processes should be transparent for their resolution. The Dean ensured debate on this issue in order to establish that all examiners were in agreement and that the process could be recorded. We consider this to be good practice. The external examiner had seen the student on the previous day, whilst the internal examiner had not, but was aware of the students academic record. One student was awarded honours, the one involved in the incident above. Recommendations 16 2 To the University Clarification of guidance for marking exams To the School First bullet regarding duplicate examination papers is not relevant to the report. 3 Bullet number 1 2 Clarity of assessments leading to proceeding to the finals exam 3 4 Clarification of guidance for marking exams Averaging percentages in the written papers 5 Issuing summary sheets to examiners before the day of the exam. We welcome the complement in regard to the usefulness of these sheets, however we place particular emphasis in the exam on patient centred lines of questioning arising from the presentation and patient examination. We do not agree with the final sentence that “if there is clear variance between examiners in any part it would be expected that the external examiner’s arbitration or assessment should prevail”. This would be contrary to University practice which states “the views of the external must be particularly influential where there is disagreement on: • the mark to be awarded for a particular unit of assessment (in borderline cases) • the final award to be delivered from the array of marks of a particular candidate at the examiners’ meeting”. We feel it is the responsibility of the University to establish its examination procedures and to determine marks and awards. The University is concerned to uphold its standards and protect these even if this is at variance with the views of external examiners. Decisions are made by the relevant Board of Examiners of which the External Examiner is a full member. We therefore allow the Externals view to be particularly influential, but not to prevail. Increasing guidance to examiners on best practice in conducting the Seen and Unseen case examinations. This only applies to the Seen Case and we plan in future to use two clinics as we do for the Unseen Case exam. The reserve examiner is available to act as supervisor. Using external examiners not from a Restorative background in the Seen case has been explained. However we are unsure what is meant in the last paragraph regarding sufficient compensation if the external examiner is not from Restorative Dentistry. Comments by external examiners regarding a small number of Seen patients, member of staff looking after individual cases. 6 7 8 9 10 Actioned Explained previously Actioned Under review Not actioned Explained opposite. Actioned Actioned Explained previously Explained previously 17