fin de grao Ophelia: Representations of Death and Madness

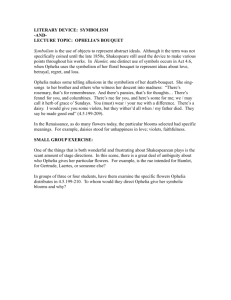

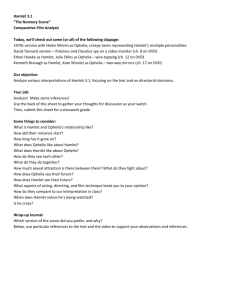

advertisement