ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

AWARDED BY NOTTINGHAM TRENT UNIVERSITY

ASSIGNMENT SUBMISSION FORM

Note: Students must attach this page to the front of the assignment before uploading to WECSERF.

For uploading instructions please see the help file online

Name of Student: DONALD WONG KIN SAN

Student Registration Number: KL419

Module Name: TME – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Module Number: WEC-MBA-08-0106

Assignment Title: AN ETHICAL ASSESSMENT OF UNOCAL

Submission Due Date: 17 JUNE 2007

Student’s Electronic Signature: Donald Wong

Plagiarism is to be treated seriously. Students caught plagiarizing, can be expelled from

the programme.

Assignment Form

MBA Jan04

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 1/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Contents

Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………… 3

1.0

Introduction …………………………………………………………………. 4

2.0

Unocal and the Court of Ethics …..………………………………………… 6

3.0

Unocal’s Moral Responsibility for the Karens ….....…………………….... 18

4.0

The Tussle between Engagement and Isolation …..……….…….….…....... 21

5.0

Conclusion ..……………………....………………………………..………. 25

6.0

References …………………………...………………….………………..... 27

Appendices

1.

Model of Ethical Decision Making …………………………..………......... 31

2.

Content Variables – Factors and Forces that Influence a Company’s Decision

Making …………………………………………………………………….. 32

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 2/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Executive Summary

Unocal was prosecuted at the court of law, and statement upon statement made by the

trial judges gave a good and reasonable indication of how the case would have been

decided. It would be reasonable to deduce that Unocal would have been found guilty,

and ordered to make hefty compensations, and undertake restitutions which will never

be known. It chose instead to make a settlement to the plaintiffs out of court.

In this paper, we subjected Unocal to the court of ethics. We appraised Unocal’s

actions in Myanmar using four theories of ethics. They are the ethical theories of

Utilitarianism, Rights, Justice, and Care. Each theory was first clarified and its

principles were used to evaluate Unocal’s actions. All four theories unanimously

found Unocal guilty of moral irresponsibility which rendered their deeds in Myanmar

unjustified. We have therefore found a positive correlation between legality and ethics

in our paper.

Having clarified the discourse of the ethical theories, and using them in our analysis

and thinking, we articulated a verdict that Unocal was morally responsible for the

atrocities committed on the minority Karens. In the final part, we discussed the moral

tussle between choosing to engage or disengage, and proposed our views on why we

thought Unocal was mistaken in adopting the premise that engagement is better than

isolation in dealing with rogue regimes.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 3/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

1.0

Introduction

At first it seems oxymoron that an oil and gas company should ask “Profits and

Principles – is there a Choice?”1 After all we know that “the social responsibility of

every business is to use its resources to increase its profits, and to maximize

shareholder value” (Friedman, 1970, p.125 cited in Laszlo and Nash, 2007;

Gallagher, 2005). However the recent downfalls of corporate icons such as Arthur

Andersen, Barings Bank, Enron, WorldCom appear to be prima facie evidence that

increased attention to business ethics is warranted. Suddenly the tagline from Shell’s

commercial does not seem naïve anymore. Instead it asks us the same poignant

question when we face challenging ethical dilemmas – when we wrestle with our

conscience to decide between right and wrong or good and evil (Velasquez, 2006).

What is ethics? The body of literature offers many varying definitions. We prefer

Velasquez (2006, p. 10) who defined ethics as “the discipline that examines one’s

moral standards or that of a society.” Takala (2006, p. 1) saw ethics from Aristotle’s

proposition of virtue, and posited an interesting definition: “ethics means pursuing the

good life.”

Given that understanding, defining business ethics becomes easy. It is simply a type

of applied ethics – a study and determination of moral right and wrong as applied to

business organisations (Velasquez, 2006). It can also be understood as the pursuit of

a good business life (Takala, 2006).

Contrary to descriptive study which makes no attempt at reaching conclusions, an

ethicist employs normative study to conclude if an action is good or bad or right and

wrong2. Normative study tries to deliver moral verdicts using ethical theories on three

different kinds of issues: systemic, corporate, and individual (Velasquez, 2006).

1

Shell’s advertisement in the National Geographic magazine, May 1999 issue.

The differences between these two schools of taught can be better understood by clarifying the

approaches they employ. While “descriptive” tells us how the world is, “normative” claims of how the

world should be. Thus something which is legal may not be ethical. However what is ethical is usually

and almost always legal (Doost, 2005).

2

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 4/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Ethical theories are customarily divided into two groups, usually called teleogical and

deontological (Boatright, 2007). Although both groups have each spawned many

theories, the most prominent of a teleogical and deontological theory are utilitarianism

and the ethical theory of Immanuel Kant respectively (Boatright, 2007; Takala, 2006;

Doost 2005; Sintonen and Takala, 2002; O’Hara, 1998). Takala (2006) also says that

utilitarian – the ethics of utility, and deontology – the ethics of duty are the ethical

grounds most commonly used to reflect on ethical issues.

In the next section, we will use utilitarianism and the three prominent schools of

deontology – rights, justice and caring to assess if Unocal’s actions in Myanmar were

morally right and therefore justified.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 5/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

2.0

Unocal and the Court of Ethics

The life which is not examined is not worth living (Plato).

Global companies, operating in foreign host countries with dissimilar cultures and

laws, political institutions and ideologies, commercial practices and customs, and

levels of economic development, are confronted with different ethical standards with

which they gauge their conduct and ascertain their moral responsibilities.

It is tempting in such circumstances to adopt the theory of ethical relativism – under

which something can be judged to be morally good if, in one particular society, it

complies with the prevailing moral standards, but wrong if it does not – and to declare

that the proposed practice or activity is morally acceptable, because is conforms with

the moral standards or practices of the particular society (Silbiger, 1999).

It may be equally tempting to insulate or disassociate itself from questionable conduct

of its host country partner, so that repercussions are muted or avoided (Schoen et al.,

2005). Highly profiled companies like ChevronTexaco, ExxonMobil, Nike, Shell, and

Unocal have all treaded the same path of escape when they faced liability for the

misconduct of third-world governments (Olsen, 2002; Schwartz, 2000).

Unocal knew for a fact that their foray into Myanmar would entail violations of

human rights including forced labour, murder, rape and torture – perpetrated by the

Myanmar military in developing a gas pipeline, and yet it decided to proceed anyway

to engage with the ruling junta (EarthRights International, 2005; Eviatar, 2005;

Holliday, 2005; Rosencranz and Louk, 2005; Schoen et al., 2005). The US Ninth

Circuit Court of Appeals in its landmark decision to allow foreign nationals to sue

American companies for specific and egregious violations of human rights committed

on foreign soil through the use of the Alien Tort Claims Act, had ascertained that

Unocal had indeed committed the actus reus (a wrongful deed) and mens rea (a

wrongful intention) of aiding and abetting human rights law violations in Myanmar

(Rosencranz and Louk, 2005; Schoen et al., 2005).

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 6/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Besides jus cogens3 violations, Olsen (2002) contended that Unocal was responsible

for causing the destruction of wetlands and mangrove ecosystems of the Yadana

region as a result of its pipeline construction.

Unocal was found wrong by the court of law (though a sentence was never meted).

We will now subject it to the court of ethics – where the judges are Utilitarianism,

Rights, Justice and Care.

2.1

Utilitarianism

It focuses on the value of the consequences or impacts, and hence it is

also referred to as the Consequential approach (Doost, 2005; Kaptein

and Wempe, 2002). In the words of its founder, Jeremy Bentham, it

approves or disapproves every action whatsoever on the basis of the

tendency it has to augment or diminish the happiness of the parties

whose interests are at stake. The choice is made in accordance with the

greatest benefit for the greatest number of stakeholders at the lowest

possible cost (Velasquez, 2006; Doost, 2005, Sintonen and Takala,

2002).

Utilitarian ethics claims that material utility and hedonistic pleasure are

the only intrinsic values to a person. As a theory of personal morality

and public choice, it expounds (just as Kantianism does) the notion that

morality rests on universalisable, objective, and rational rules of

decision making (O’Hara, 1998).

It is the most pervasive ethics theory, and its influence prevails till

today. Takala (2006) asserts that utilitarianism is the ideological basis

for modern economics, and serves to guide the government of many

3

Jus cogens means violations of norms of international law that are binding on nations even if they do

not agree to them. Such atrocities include torture, forced labour, murder, rape and slavery. The judges

in Unocal’s case found the company guilty of jus cogens violations on the Myanmar people (Schoen et

al. 2005).

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 7/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

countries in policy-making. The concept of the ‘rational economic

man’ was plausibly founded on utilitarianism. Velasquez (2006)

suggests that modern management techniques such as cost-benefit

analysis and cost-efficiency were based on utilitarianism. It is so

ubiquitous that Nantel and Weeks (1996) argue that the definition and

practice of marketing are almost entirely utilitarian4 (and ironically

marketing is often deemed controversial under the light of ethics).

As O’Hara (1998) puts it, only economic, social, and ecological

functions that promotes sustainable economic growth are taken into

account in utilitarian thinking – and this appeared to have been

Unocal’s prescription of corporate ethics.

Figure 1: Framework of utilitarian ethics

Source: O’Hara (1998), p. 49

The Utilitarian judge will now ascertain Unocal, and dispense

judgement based on the decision of a panel of jury comprising the six

theses of utilitarianism given in Boatright (2007).

4

The authors were referring to Kotler and Turner’s (1981) definition of marketing: “Marketing is

human activity directed at satisfying needs and wants through exchange process.”

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 8/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Consequentialism

When we try to calculate the amount of

The rightness of actions is determined utility (i.e. the balance of pleasure over

solely by the consequences.

pain) for each individual affected by

Unocal’s actions (including the company

itself), and that for the whole society, we

see the scale tilting towards pain which

clearly outweighs pleasure.

Hedonism

This method of assessment is very

Only pleasure is ultimately good and pain arbitrary. There is hardly any action

is absent.

where pain is absent. Instead there is

almost always an opportunity cost for

every action taken. In Unocal’s case, the

revenue from oil (typifying pleasure) was

transacted with the blood (typifying pain)

of the local people.

Maximalism

Understood arithmetically, action A is

A right action is the one that has the justified if A > (B+C+D+E+…). In

greatest amount of good consequences performing

this

assessment,

it

is

possible when the bad consequences are important that we be dispassionate lest

also considered.

we be swayed. Because it is arbitrary, this

thesis could produce greater utility for

Unocal if it so elects to magnify the good,

and ignore the bad variables. A bad

action could thus be vindicated by

ignoring

foreseeable

negative

consequences.

Universalism

While this requires people to think in

The pleasure and pain of everyone alike holistic terms, it is not useful in gauging

must be considered.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

the level of utility in the pleasure-pain

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 9/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

equilibrium.

Act-Utilitarianism (AU)

This resembles maximalism but worded

An action is right if and only if it more strongly. It is also clearer and thus a

produces the greatest balance of pleasure better aid for ethical decision making.

(benefit) over pain (cost) for everyone.

And like consequentalism, AU would

dictate an inequilibrium when there is a

greater imbalance of pain over pleasure

as in the context of Unocal.

Rule- Utilitarianism (RU)

In terms of specificity, clarity, and

An action is right if and only if it practical for use, RU is superior to AU.

conforms to a set of rules the general The result of utility calculation using RU

acceptance of which would produce the is

similar

to

those

of

AU

and

greatest balance of pleasure over pain for consequentalism.

everyone.

The jury would deliver a 3-1 majority decision with 2 abstaining. The

utilitarian judge would thus pronounce a verdict that Unocal’s deeds

were wrong and therefore unjustified.

2.2

Rights

Rights play an important role in business ethics, and indeed, in

virtually all moral issues. It holds that decisions must be

consistent with fundamental rights and privileges, such as the

right to privacy, freedom of conscience, and property

ownership (Boatright, 2007; Velasquez, 2006; Richter and

Buttery, 2002). Consequently rights may be understood as

entitlements (Boatright, 2007; Velasquez, 2006).

There are several different types of rights.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 10/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

2.2.1

Legal Rights

These are rights recognised and enforced as part of a

legal system.

2.2.2

Moral Rights

Unlike legal rights, moral rights are not limited to a

particular jurisdiction. They are the birthright of every

person, and have universal value in that everyone

irrespective of colour, gender, and nationality possesses

in equal amount by simply being human (Velasquez,

2006).

2.2.3

Specific Rights

These are specific to identifiable individuals. A major

source of specific rights is contracts which bind parties

to mutual rights and duties. In practice, special rights

can cover people group. The Malays in Malaysia for

example, enjoy special economic rights under a social

contract created just before the Independence.

2.2.4

General Rights

These are accorded to humanity in general (albeit with a

Western slant). They include right of free speech, right

to safety and protection, right for education, right to

work, right to free pursuit of interests, etc. These rights

are universal, unconditional (or inalienable), generally

autonomous, and are for the large part, enshrined in the

constitution of most democratic countries.

The two other distinguishable kinds of rights which we

will not delve into are Negative and Positive Rights.

Rights depart from utilitarianism in several ways. Rights require

morality from an individual’s perspective whilst utilitarian holds the

view of a society at large, and promotes its aggregate utility. John

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 11/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Locke and his contemporary Immanuel Kant are the major proponents

of the ethical theory of rights.

The Kantian ethics is based on a moral principle named categorical

imperative – everyone should be treated as a free person equal to

everyone else, and everyone has the correlative duty to treat others in

this way (Velasquez, 2006; Trevino and Nelson, 2004). Kant borrows

heavily from the Golden Rule in Christian thought – do to others as

you would want them to do to you, in expounding his two criteria for

determining moral right and wrong – universability and reversibility.

In stark contract to the utilitarian principle, Kantian theory focuses on

motives instead of the consequences of external actions. He denounces

treating people only as means. He argues that people should instead

and always be treated as ends (Velasquez, 2006; Trevino and Nelson,

2004; Kaptein and Wempe, 2002).

O’Hara (1998) has put forward a framework for the ethics of rights

(and also justice) that bears stark contrast with the utilitarian ethics.

Figure 2: Framework of rights and justice (Kantian) ethics

Source: O’Hara (1998), p. 53

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 12/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

The Rights judge will now deliver its judgement based on a jury that

consists of the two criteria, and one maxim given in Velasquez (2006).

Universability

Kantian tradition would have Unocal act

One’s reasons for acting must be reasons the way the vast majority would – to

that everyone could act on at least in abstain from indulging in activities that

principle.

would violate human rights.

Reversibility

The company’s action was ethically

One’s reasons for acting must be reasons irreversible – it would have neither

that he or she would be willing to have subjected itself (or the American people)

others use, even as a basis of how they to any foreign colonisation nor any of the

treat him or her.

atrocities that were inflicted on the

Karens.

Maxim

Unocal used the second part of this

Never use people merely as means but maxim to argue that their project had

always respect and develop their ability benefited the locals by improving their

to choose for themselves.

standard of living. They have however

craftily sidestepped the first part of the

maxim – never use others as a means to

advance one’s purpose. Their defence

was therefore hollow.

The criteria and maxim of rights would therefore judge Unocal guilty

of moral misgivings, and their deeds unjustified.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 13/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

2.3

Justice

Aristotle, the most prominent advocate of the classical ethics theory of

justice proposed three forms of justice (Boatright, 2007).

2.3.1

Distributive justice, which deals with the distribution of

benefits and burdens;

2.3.2

Compensatory justice, which is a matter of compensating

persons for wrongs done to them; and

2.3.3

Retributive justice, which involves the punishment of

wrongdoers.

Among the three kinds of justice, distributive is comparative while

compensatory and retributive are both non-comparative. Distributive justice is

comparative – it considers not the absolute amount of benefit and burdens of

each person but each person’s amount relative to that of others. Conversely the

non-comparative determines the amount of compensation owed to the victim

or the punishment due to a crime based on the features of each case, rather

than a comparison with other cases (Boatright, 2007; Velasquez, 2006).

Decisions and behaviours are judged by their consistency with an equitable

and impartial distribution of benefits and costs among individuals and groups.

John Rawls, famed for his egalitarian theory of justice as equality and fairness,

postulated that social and economic inequalities are permissible and are

compatible with justice – provided that opportunities are fair and open for all

to gain access to them, and that the least advantaged must have a fair slice of

the benefits (Boatright, 2007; Velasquez, 2006; Kaptein and Wempe, 2002;

Richter and Buttery, 2002). His proposition spawned modern concepts such as

the difference principle (in every distribution there is a worst-off person), and

the modern mantra of equal opportunity.

Justice will now pronounce its judgement based on a jury comprising the four

criteria discussed above.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 14/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Distributive justice

Unocal and Total’s investment in the

The distribution of benefits and burdens.

Yadana field had only benefited people in

that area, and the ruling military junta

(Htay, 2005; Schoen et al., 2005). The

rest of Myanmar continue to suffer the

consequences of a degraded environment,

and

expanded

political

oppression

(Carter, 2004). Clearly the principle of

distributive

justice

was

flagrantly

violated.

Compensatory justice

The plaintiffs (villagers i.e. Doe) in Doe

Compensating persons for wrongs done v. Unocal were compensated by the

to them.

defendant (Unocal) in an out-of-court

settlement (Eviatar, 2005; Rosencranz

and Louk, 2005). Hence compensatory

justice was served albeit not by a court of

law.

Retributive justice

As the Doe v. Unocal case was ordered to

Punishment of wrongdoers.

be reheard en banc, a sentence was not

pronounced, and thus, the perpetrators

were not punished (Rosencranz and

Louk, 2005).

Egalitarian justice

Forced labour, arbitrary arrests, murder,

The basic liberty of every person must be rape, etc. were among the atrocities

protected from invasion by others, and committed by the Unocal-Total-junta

must be equal to those of others.

collusion.

Egalitarian

justice

would

denounce the deplorable action of Unocal

to its eternal shame.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 15/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

The court of Justice would therefore find it straightforward to arrive at a

decision to pronounce Unocal guilty of breaching all four theories of justice.

2.4

Care

Our literature review shows that Velasquez (2006) and O’Hara (1998)

are the only proponents of the ethical theory of care. Care places

emphasis on caring for the concrete well-being of people close to us

(Velasquez, 2006). It was founded on Carol Gilligan’s research on

Kohlberg’s stages of moral development.

According to O’Hara (1998), care brings the devalued life world of

women, ethnic minorities and marginalised groups in society to

attention, and reevaluates it. She also argues that reciprocity,

mutuality, and relationality are at the centre of a care-based ethics.

Consequently the invisible connections of human dependence on the

sustaining function of families, the subsistence sector, and ecosystems

become visible.

The ethics of care therefore advocates the sustainable interdependence

between human beings and the environment, and promotes the need to

conserve its symbiotic relationship – the yin and yang for present and

future generations.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 16/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Figure 3: Framework of the ethics of care

Source: O’Hara (1998), p. 57

When we appraise Unocal from the perspective of care, we can clearly

see that the company had negated its duty to society and the

environment. By turning a blind eye to the sufferings of the locals

(pain) to achieve profit goals (utility/pleasure), it also jeopardised the

harmony between the land and its inhabitants. The judge of care would

then declare Unocal wrong, and its actions unjustified.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 17/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

3.0

Unocal’s Moral Responsibility for the Karens

Myanmar, then Burma has been ruled by a fraternity of military elitists for 45 years

since a March 1962 coup. It has since brutally suppressed every pro-democracy

movement. In May 1990, the junta ignored a nationwide general election that gave a

landslide victory to Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, and has

since 1991 to this very day, consigned the Nobel peace laureate to house arrest.

According to the 1983 census, the Karens constitute only 6.2 percent of the whole

Myanmar population. Together with the Karenni and the Shan, the Karens are the

most severely marginalised, discriminated, and ostracised ethnic groups by the ruling

junta, and consequently they received the worst forms of treatments (Htay, 2005). The

SLORC, whom Unocal partnered, adopted the policy of “draining the ocean so that

the fish cannot swim” in quelling any form of armed resistance. It simply means

undermining the opposition by attacking the civilian population until it can no longer

bear to support the opposition (Htay, 2005, p.45). Egregious atrocities, murders,

forced labour, and human rights violations of all kinds and magnitude have been

committed by the trigger-and-torture-happy SLORC.

Against this backdrop, is Unocal morally responsible for the sufferings and the losses

of the Karens in the Yadana project? Well the US courts thought so, and we are

unequivocally in agreement with them.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises “the inherent dignity and the

equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family as the foundation of

freedom, justice, and peace in the world” (United Nations, 1948 cited in Schoen et

al., 2005). This is a very egalitarian, rights, and caring definition from the perspective

of ethical theories. Abetting with the SLORC, and condoning the outrageous

violations of life, liberty, and property are universally wrong. One ought to know that

these activities are wrong: one ought not to murder, rape, torture, and enslave, and

hence, one ought not to cooperate with those who do these activities.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 18/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

The claim Unocal made to separate itself from the actions of the military will not hold

up to ethical scrutiny. Unocal is an immediate implicit material cooperator in the

action of the Myanmar military. Unocal and the Myanmar military both had the same

object as goal, Unocal was aware of the activity of the military in support of that

shared goal, and Unocal supplied the military with the material means to secure the

shared objective. In its failure to explicitly disclaim the activities of the military,

Unocal’s cooperation is implicit. Immediate material cooperation in egregious human

rights violations, even if not explicit cooperation, is always ethically wrong

(Boatright, 2007; Schoen et al., 2005; Kaptein and Wempe, 2002).

Years of economic sanctions have caused the ruling military regime to eagerly

welcome foreign investors. Holliday (2005) therefore argues that foreign companies

would be able to exert their influence on the junta to adopt some the values they

embrace in their home countries. In our opinion, Unocal could have played a role in

evangelising the Myanmar government, and in turn conducted its business in ways it

would in the US, but it chose not to. Their failure inevitably raises suspicions about

the company’s moral standards, value systems, and corporate governance. We are not

surprised if Unocal was another one of the many companies that do not walk the talk

of their corporate code of ethics.

Instead of closing its eyes to the use of forced labor by the Myanmar military, Unocal

should have investigated an appropriate wage rate to guarantee the workers earned a

just wage which would not have only permitted the workers to provide their families

with the bare necessities of life, but would have also permitted the workers and their

families to enjoy leisure, rights, and benefits appropriate to the possibility of the

‘‘good life.’’

Instead of ignoring the inclination of the Myanmar military to committing atrocities,

Unocal should have implemented processes, for instance, external international

inspections of workplace conditions to prevent such conduct.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 19/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

In place of cooperating and coordinating with the junta in effecting the pipeline

construction, Unocal could have refused to participate in the project until safeguards

against human rights violations were instituted by the Myanmar military.

Finally, Unocal, in deciding to settle the villagers’ claims out of court in lieu of a

potentially enormous legal liability is in itself an admission of guilt. While it may be

argued that the settlement was motivated by a need to salvage its reputation from

further attacks in the public court, we prefer to see it as an acceptance of moral

liability.

Our verdict is clear – Unocal ought to be held morally and materially responsible for

the Karens. Consequently it would be morally justified to compensate the defendants,

and the plaintiffs should receive due sentencing commensurate with the wrongs they

committed.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 20/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

4.0

The Tussle between Engagement and Isolation

Unocal knew the conduct and track record of their local partner in Myanmar, and they

knew too that their partner had had an appalling reputation of human rights violation –

particularly with regards to the Karen minority ethnic group. Notwithstanding these

facts, they argued that “engagement” instead of “isolation” is “the proper course to

achieve social and political change in developing countries with repressive

governments” – to justify their venture into Myanmar, and their partnership with the

ruling military regime.

Shwartz (2000) argued that Unocal’s decision to choose engagement over isolation

was founded on three reasons. First, they reasoned that their activities were not

causing any harm. They had complied with government legislations, abided by

environmental standards, and did not use slave labour. Second, they saw themselves

as catalysts for change, and therefore contended that their involvement would more

likely support democratic forces, stimulate change, increase connection with the

outside world, and ensure that the military government will not survive for long.

Third, they claimed that their participation had been legitimised by global institutions

like the World Bank, the IMF, ASEAN, and other international organisations that

have been funding and supporting economic and social projects in Myanmar. They

had earlier refused to participate in a lucrative project in Afghanistan because the

World Bank, IMF, and others would not participate but Myanmar was different.

Hence, they could not see a reason for abstinence.

While the arguments appear to have a certain degree of plausibility, they were flawed.

It is our contention that absolving their responsibility is akin to acquitting a drunkard

who pleads innocence on grounds of drunkenness after going on a shooting spree

injuring and killing others. Like the drunken person, Unocal’s actions may not have

been driven by mala fide5 per se, but we argue that they had been negligent for failing

to calculate the costs of injuries, and human rights violations. Their cost and benefit

analysis was myopic, and probably skewed to simply evaluating the potential profits it

5

A legal term that means done in bad faith.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 21/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

might earn in the pipeline project instead of evaluating the social benefits against the

detriments to the Myanmar citizens resulting from the project – an evaluation that

might very well have been undertaken by the jury in consideration of the case at trial.

Unocal had also ignored a 1997 Presidential order to ban U.S. investments in

Myanmar until democratisation, and respect for human rights were evident. To the

eternal ignominy of Unocal’s leaders, they had invested in a country which was the

world’s leading producer of opium and heroin, and tolerates drug trafficking and

traffickers in defiance of the views of the international community (Hadar, 1998).

Consequently, we are in the opinion that Unocal was mistaken for choosing

engagement over isolation. Schwartz (2000) argued that a rule of thumb for

engagement to succeed is the presence of transparency, where for example, Amnesty

International and other organisations are permitted to enter the country, and observe

the conditions people are experiencing. Myanmar had none.

Contrary to Unocal’s stance, we support isolating developing countries with

repressive and recalcitrant governments for five reasons. First, substantial foreign

investments have not achieved positive outcomes. There have been instances where

corporate investments have contributed to conflict and human rights abuses (Anon,

2006; Htay, 2005; Schoen et al., 2005; Olsen, 2002; Schwartz, 2000). Despite the

existing trade and investment barriers, foreign investment in energy and mining

enterprises in Myanmar has become a significant source of revenue for the current

regime. Such projects rarely produce tangible financial benefits to the general

population and arguably further entrench the regime (Htay, 2005; Carter, 2004).

Against popular belief, the much touted prescription of engagement ironically

strengthens the ruling regimes – the very shackles and chains it was supposed to

loosen.

Second, engagement does not foster the much touted economic development that

necessarily leads to improvement of human rights, and a democratic government.

Myanmar’s inclusion into the ASEAN fraternity has proven that. The relationship

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 22/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

between economic prosperity and growth and political liberalisation is complex, and

there is therefore no causal link between democracy, respect for human rights, and

economic development. (Forcese, 2002 cited in Carter, 2004).

Third, any hope for engagement to succeed is an illusion. Proponents once believed

ASEAN could strategically influence the junta to change. The truth now evident is

this group, known for its long tradition of consensus, is divided on how to handle

Myanmar. While Malaysia and Philippines continue to be vocal in calling for change,

Singapore and Thailand have been reluctant to act because of their heavy investments

in Myanmar (Zulkafar, 2007). Hence the junta no longer takes ASEAN seriously

because they know ASEAN cannot come to a cohesive agreement.

Four, it is simply impossible to do business in such countries without directly

supporting their rogue governments, and their pervasive human rights violations. For

business to take place, foreign companies are required to form joint-ventures with

state-controlled companies, which are in turn steered by the appointed proxies

(Holliday, 2005). It is therefore difficult to imagine how such JV companies can

conduct their business in neutrality when it is covenanted with a local partner that

serves the interest of the abhorrent government it represents.

Five, as the foreign investments do not translate into infrastructure or sustainable

employment for the population, it is our contention that a disengagement strategy,

withdrawal, and banning investments would not negatively affect the innocent

population. It will instead achieve the goal of cutting off the lifeline of the ruling

government as it heavily relies on capital from the investments. Taking a utilitarian

view to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number, we postulate that some

arm-twisting is necessary (and justified) when the road of diplomacy has ended.

In light of Myanmar, we do however realise that any isolation effort will be

undermined by the willingness of ASEAN nations to trade with and support the

regime. And even more detrimental is China and Russia’s economic interests in

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 23/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Myanmar. Both countries are heavy investors in Myanmar’s natural resource sectors

like oil, gas and timber (Zulkafar, 2007; Carter, 2004). Further they are veto-wielding

members of the powerful UN Security Council, and may therefore block any hard-line

action against Myanmar.

In the final analysis, we argue that it is not the duty of any companies to stimulate

political change in any country, what more in hardcore military regimes like

Myanmar. This issue is beyond one company, and it is even larger than a regional

caucus of nations like ASEAN. It is also inconceivable to expect multinational

companies to collaborate in unison to boycott Myanmar. Nonetheless companies do

have a moral and societal obligation to fulfil, and when faced with tough dilemmas, it

is our contention that they should choose principles over profits.

We suggest companies to consider using McDevitt et al.’s (2007) model in its ethical

decision making process, and this is provided in Appendix 1. This model may be

useful in helping companies embroiled in the tussle between engagement and

isolation. We have also included as Appendix 2, a framework of factors and forces

that shape and reshape a company’s decision making process.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 24/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

5.

Conclusion

Ethics is a fertile ground for animated debates as it often has are no definitive

answers. It is a playground for academic research where theorists can indulge in

eternal disputes with each other over differing interpretation and dispensation of

theories and principles in confronting ethical dilemmas.

Ethics is hot property. It is no empty philosophical abstraction. The fall from grace of

various corporate icons of our generation has fuelled the interests of colleges,

universities, businesses, governments, and societies to engage in the appreciation,

critique, and application of ethical principles and conduct in everyday life.

Increasingly companies awakening to the motives behind embracing codes of ethics,

and good values at its core. And today, more and more books are written about

corporate governance and corporate social responsibility than anytime before in

history.

In this era of globalisation and heightened ethical sensitivity, companies, in their

business activities must benefit both shareholders and stakeholders. Losing sight of

either or favouring one more than the other is a good prescription for costly troubles

later on. There is ample evidence in the body of literature and the practitioner to

support ethical business conduct. Further there is a suite of ethical theories that can

serve to guide ethical direction, diagnose and clarify ethical dilemmas, and provide

the framework to evaluate business strategy ethically prior to implementation.

Ethical behaviour is a good long-term business strategy. We tend to agree with

Velasquez’s (2006) observation that over the long run, and for the most part, ethical

behaviour can give the company significant competitive advantages over companies

that are not ethical. This is not a naïve presumption because we acknowledge ethical

behoaviour can impose losses on the company, and unethical behaviours sometimes

pays off. Obviously not all unethical business practices get punished, and certainly not

all ethical endeavours engender rewards.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 25/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Had Unocal thought and managed ethically, it would have decided against venturing

into Myanmar, and thus averted the sufferings and loss of untold human lives. It

would have also saved itself from the damning reputation from the trial, and perhaps

still be in business today.

For Unocal, dabbling in a foreign country with a repressive military government was

not worth it. In fact, it was wrong. Their strategy of engagement was misguided and it

backfired.

Unocal is history. It is in the power and duty of business leaders and managers today

and the future to choose to run their business ethically. When they are confronted with

the question – Profits or Principles – Is there a Choice? We urge them to answer with

a resounding Yes!

Word count: 3,885 words

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 26/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

References

1.

Books

Boatright, J.R. (2007), Ethics and the Conduct of Business, 5th ed., Pearsons/Prentice

Hall, New Jersey.

Kaptein, M. and Wempe, J. (2002), The Balanced Company: A Theory of Corporate

Integrity, Oxford University Press, New York.

Trevino, L.K. and Nelson, K.A. (2004), Managing Business Ethics: Straight Talk

About How To Do It Right, 3rd ed., Wiley, New Jersey.

Silbiger, S. (1999), The 10-Day MBA, Piatkus Publishers, London.

Velasquez, M.G. (2006), Business Ethics: Concepts and Cases, 6th ed.,

Pearson/Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

2.

Journal Articles and Research Publications

Anon. (2006), “Strange bedfellows: the uneasy relationship between big business and

ethical principles,” Strategic Direction, Vol. 22, No. 10, pp. 9-12.

Anon. (2005), “Ethics is just about doing the right thing: Shell shocked and IBM goes

fact-finding,” Strategic Direction, Vol. 21, No. 7, pp. 14-17.

Carter, J. (2004), “Economic pressure: the political currency of the Burmese junta;

reform through disengagement,” Legal Issues on Burma Journal, No. 19, pp. 10-34.

Doost, R.K. (2005), “The curse of oil! Search for a formula for global ethics,”

Managerial Auditing Journal, Vol. 20, No. 8, pp. 789-803.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 27/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Gallagher, S. (2005), “A strategic response to Friedman’s critique of business ethics,”

Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 26, No. 6, pp. 55-60.

Hadar, L.T. (1998), “U.S. sanctions against Burma: a failure on all fronts,” Trade

Policy Analysis, March 26, Centre for Trade Policy Studies, available at

http://www.cato.org/pubs/trade/tpa-001.html, accessed 28 May 2007.

Htay, S. (2005), Economic Report on Burma 2004/05, Federation of Trade Unions

Burma, pp. 1-79.

Holliday, I. (2005), “Doing business with rights violating regimes: corporate social

responsibility and Myanmar’s military junta,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 10,

No.61, pp. 329-342.

Laszlo, C. and Nash, J. (2007), “Six facets of ethical leadership: an executive’s guide

to the new ethics in business,” Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and

Organisation Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 1-6.

Lloyd, B. and Kidder, R.M. (1997), “Ethics for the new millennium,” Leadership and

Organisation Development Journal, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 145-148.

McDevitt, R., Giapponi, C and Tromley, C. (2007), “A model of ethical decision

making: the integration of process and content,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 73,

No. 2, pp. 219-229.

Nantel, J. and Weeks, W.A. (1996), “Marketing ethics: is there more to it than the

utilitarian approach,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 9-19.

O’Hara, S.U. (1998), “Economics, ethics and sustainability: redefining connections,”

International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 43-62.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 28/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Olsen, J.E. (2002), “Global ethics and the Alien Tort Claims Act: a summary of three

cases within the oil and gas industry,” Management Decision, Vol. 40, No. 7, pp. 720724.

Richter, E.M. and Buttery, E.A. (2002), “Convergence of ethics?” Management

Decision, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 142-151.

Sargent, T. (2007), “Toward integration in applied business ethics: the contribution of

humanistic psychology,” Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organisation

Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 1-22.

Schoen, E.J., Falchek, J.S. and Hogan, M.M. (2005), “The Alien Tort Claims Act of

1789: globalisation of business requires globalisation of law and ethics,” Journal of

Business Ethics, Vol. 10, No.62, pp. 41-56.

Schwartz, M. (2007), “The ‘business ethics’ of management theory,” Journal of

Management History, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 43-54.

Schwartz, P. (2000), “When good companies do bad things,” Strategy and

Leadership, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 4-11.

Sintonen, T.M. and Takala, T. (2002), “Racism and ethics in the globalised business

world,” International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 29, No. 11, pp. 849-860.

Takala, T. (2006), “An ethical enterprise: what is it?” Electronic Journal of Business

Ethics and Organisation Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 4-12.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 29/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

3.

Electronic and Print Media

EarthRights International (2005), “Doe v. Unocal case history,” EarthRights

International, January 30, available at:

http://www.earthrights.org/site_blurbs/doe_v._unocal_case_history.html,

accessed 13 May 2007.

Eviatar, D. (2005), “A big win for human rights,” The Nation, April 21, available at:

http://www.thenation.com/doc/20050509/eviatar, accessed 14 May 2007.

Rosencranz, A. and Louk, D. (2005), “*135 Doe v. Unocal: holding corporations

liable for human rights abuses on their watch,” Chapman Law Review, Spring 2005,

available at:

http://www.laborrights.org/press/Unocal/chapmanlawreview_spring05.htm,

accessed 13 May 2007.

Zulkafar, M. (2007), “Not so good a friend after all,” The Star, May 30.

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 30/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

Appendix 1

Model of Ethical Decision Making: Process and Content

Source: McDevitt et al., (2007, p. 223)

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 31/32

ASSIGNMENT – THINKING AND MANAGING ETHICALLY

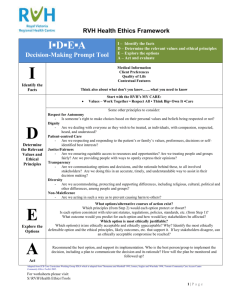

Appendix 2

Content Variables – factors and forces that influence a company’s decision making

Source: McDevitt et al., (2007, p. 221)

Prepared by Donald Wong (OCKL: KL419)

Due Date: 17/6/07

Page 32/32