Assessing Capabilities for Innovation

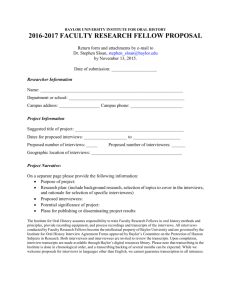

advertisement