Use of the End-to-End Anastamotic Circular Stapler for Creation of

advertisement

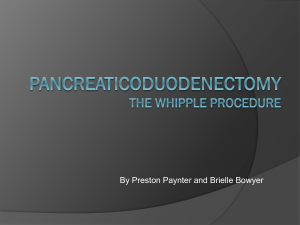

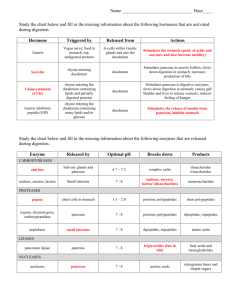

SURGEON AT WORK Use of the End-to-End Anastamotic Circular Stapler for Creation of the Duodenoenterostomy for Enteric Drainage of the Pancreas Allograft Jonathan A Fridell, MD, Martin L Milgrom, MD, PhD, FACS, Sharon Henson, LPN, CCRC, Mark D Pescovitz, MD, FACS Pancreatic transplantation offers the potential for normalization of blood sugar levels for patients with diabetes mellitus. This procedure is most often reserved for patients who will be receiving a simultaneous kidney transplant or who have already undergone renal transplantation. Historically many approaches to exocrine secretion drainage have been used, but currently pancreatic exocrine secretions are most often drained either into the bladder or small intestine. The primary advantage of bladder drainage is that it allows monitoring of urine amylase. This is particularly useful for recipients of isolated pancreas allografts in whom it is otherwise difficult to detect acute rejection. Proponents of enteric drainage believe that this technique is more physiologic than bladder drainage. Intestinal absorption of fluid and bicarbonate prevents the severe metabolic acidosis frequently associated with bladder drainage.1-3 Enteric drainage also eliminates urologic complications of bladder drainage such as hematuria, urinary tract infections, urethritis, cystitis, and reflux pancreatitis.1-5 The technical failure rate and graft survival are similar using either technique.1-7 The enteric anastamosis is normally performed between the donor duodenum and the recipient small intestine and is classically described as a two-layered handsewn anastamosis. In this article we describe a new technique applying the End-to-End Anastamotic (EEA) Curved Intraluminal Stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc) to create this anastamosis. SURGICAL TECHNIQUE The pancreas is procured using an en-bloc technique after aortic flush with preservation solution and topical cooling with saline slush as previously described.8-10 At the donor operation the proximal duodenum just distal to the pylorus and the proximal jejunum are divided with the Gastrointestinal Anastamotic (GIA) Stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc). We typically divide the small bowel mesentery with the GIA stapler as well. If the liver is simultaneously procured, as was the case in all the pancreas transplantations performed in this series, the pancreas and liver are separated on the back table while maintaining topical cold solution on saline slush. The splenic and superior mesenteric arteries are identified and tagged with polypropylene sutures for later reconstruction. The portal vein is divided approximately halfway between the pancreas and the liver. Further preparation of the graft is carried out on the back table before implantation. The mesentery is oversewn and the GIA staple line on the proximal duodenum is inverted. The pancreatic arterial supply is reconstructed with a donor iliac artery Y-graft. Typically the donor internal iliac artery is sewn to the splenic artery and the donor external iliac artery is sewn to the superior mesenteric artery using running polypropylene suture. The splenic hilar vessels are serially ligated but not divided. The distal duodenum and proximal jejunal mesentery is divided with ties, but this segment of bowel is left attached to facilitate later anastamosis to the recipient’s bowel. In the case of simultaneous kidney and pancreas transplantation, we typically implant both organs intraperitoneally to the right iliac vessels using a midline incision. Ligation and division of all internal iliac veins facilitate this approach by reducing tension on the venous anastamosis. The portal vein and the pancreatic Y-graft are anastamosed to the right common iliac vein and artery, respectively. The kidney is placed only after No competing interests declared. Received June 11, 2003; Revised September 10, 2003; Accepted September 12, 2003. From the Department of Surgery, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN. Correspondence address: Jonathan A Fridell, MD, Department of Surgery, Indiana University School of Medicine, 550 N University Blvd, #4258, Indianapolis, IN 46202. © 2004 by the American College of Surgeons Published by Elsevier Inc. 495 ISSN 1072-7515/04/$30.00 doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.09.006 496 Fridell et al EEA Circular Stapler for Duodenoenterostomy J Am Coll Surg Figure 1. (A) End-to-End Anastamotic (EEA)-stapled duodenoenterostomy. The anvil of the EEA stapler is inserted into the jejunum through an enterotomy and secured with a purse-string suture. The EEA stapler device is advanced into the second portion of the donor duodenum through the open jejunal end, reattached to the anvil, closed, and then fired, creating the anastamosis. (B) The distal donor duodenum and jejunum are then removed with a single fire of a Gastrointestinal Anastomatic stapler. (From: Indiana University School of Medicine, Office of Visual Media, with permission.) completion of the pancreas transplantation. This allows cross-clamping of the external iliac vessels without interrupting the blood flow to the pancreas. If the patient has had a previous right-sided kidney transplantation, the pancreas may still be placed on the common iliac vessels on the right side or on the left iliac vessels if necessary. In all cases, the pancreas was positioned with the tail toward the pelvis and the head and duodenum oriented superiorly to facilitate creation of a tension-free enteric anastamosis. The spleen, which is not revascularized, is removed after reperfusion of the pancreas graft. After the pancreas has been reperfused and hemostasis obtained, a circular EEA stapler is selected by passing metal sizers into the duodenum through the jejunal end of the donor bowel. The recipient site for the enteric anastamosis is typically selected in the proximal jejunum in a portion that reaches the pancreas without tension. Noncrushing bowel clamps are applied proximally and distally to the proposed recipient anastamosis site. A full-thickness purse-string suture is placed on the antimesenteric side and an enterotomy is created. The anvil of the EEA stapler is removed and placed into the jejunum through the enterotomy and the purse-string su- ture is tied. The stapler device is advanced into the second portion of the donor duodenum through the open jejunal end. The rod projecting from within the ring of staples is pushed through the wall of the duodenum opposite the ampulla. The anvil is then reattached to the stapler rod projecting from the duodenum, closed, and fired, creating the anastamosis (Fig. 1A).The distal donor duodenum and jejunum are then removed with a single fire of a GIA stapler (Fig. 1B). The EEA circular stapler was used to construct the duodenoenterostomy in 14 pancreas transplantations performed at our institution between July 2002 and May 2003 with a mean followup of 4.3 ⫾ 2.4 months (range 1 to 8 months). Ten patients underwent simultaneous kidney and pancreas transplantation (nine men, one woman, mean age at transplantation 37 ⫾ 9 years). Three patients underwent pancreas transplantation after kidney transplantation (two men, one woman, mean age at transplantation 36 ⫾ 9 years, mean time to pancreas transplantation 3.4 ⫾ 2.8 years after renal transplantation), and one patient (a woman, age 22 years) underwent simultaneous liver and pancreas transplantation for cystic fibrosis. Patients receiving simultaneous kid- Vol. 198, No. 3, March 2004 Fridell et al ney and pancreas transplants received induction therapy with rabbit antithymocyte globulin, steroid withdrawal by postoperative day 5, and maintenance therapy with tacrolimus and sirolimus as described by Kaufman and colleagues.11 Recipients of pancreas transplants after previous renal transplantation received similar induction and maintenance treatment, with rapid weaning of the steroids to 2.5 mg of prednisone daily. DISCUSSION The anastamosis was found to be easy and quick to perform. One of these transplants was complicated by a small bowel obstruction resulting from an internal hernia posterior to the enteric anastamosis. This subsequently placed tension on the staple line, causing an anastamotic leak. This was corrected by reducing the hernia, repairing the retropancreatic defect, and suturing the opening in the anastamotic staple line. The enteric anastamosis did not require revision. All pancreas grafts are functioning well at a mean followup of 2.79 ⫾ 2.12 months. In summary, in this article we have described a new technique for creating the duodenoenterostomy necessary for enteric drainage of the pancreatic allograft exocrine secretions. This procedure is easy and quick to perform with a low complication rate. A similar technique was described for performing the duodenoneocystostomy for bladder drainage.12-15 REFERENCES 1. Pearson TC, Santamaria PJ, Routenberg KL, et al. Drainage of the exocrine pancreas in clinical transplantation: comparison of bladder versus enteric drainage in a consecutive series. Clin Transplant 1997;11:201–205. 2. Bloom RD, Olivares M, Rehman L, et al. Long-term pancreas allograft outcome in simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation: a comparison of enteric and bladder drainage. Clin Transplant 1997;64:1689–1695. 3. Pirsch JD, Odorico JS, D’Alessandro AM, et al. Posttransplant 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. EEA Circular Stapler for Duodenoenterostomy 497 infection in enteric versus bladder–drained simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 1998;66: 1746–1750. Sollinger HW, Odorico JS, Knechtle SJ, et al. Experience with 500 simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants. Scientific papers of the American Surgical Association. Ann Surg 1998;228:284– 296. Kuo P, Johnson L, Schweitzer EJ, et al. Simultaneous pancreas/ kidney transplantation—a comparison of enteric and bladder drainage of exocrine pancreatic secretions. Clin Transplant 1997;63:238–243. Busing M, Martin D, Schulz T, et al. Pancreas-kidney transplantation with urinary bladder and enteric exocrine diversion: seventy cases without anastomotic complications. Transplant Proc 1998;30:434–437. Fernandez-Cruz L, Astudillo E, MacMillan N, et al. Should enteric drainage be used as a primary procedure instead of bladder drainage in clinical pancreas transplantation? Transplant Proc 1998;30:430–431. Dodson F, Pinna A, Jabbour N, et al. Advantages of the rapid en bloc technique for pancreas/liver recovery. Transplant Proc 1995;27:3050. Imagawa DK, Olthoff K, Yersiz H, et al. Rapid en bloc technique for pancreas-liver procurement. Improved early liver function. Transplantation 1996;61:1605–1609. Pinna AD, Dodson F, Smith CV, et al. Rapid en bloc technique for liver and pancreas procurement. Transplant Proc 1997;29: 647–648. Kaufman DB, Leventhal J, Koffron AJ, et al. A prospective study of rapid corticosteroid elimination in simultaneous pancreaskidney transplantation: comparison of two maintenance immunosuppression protocols: tacrolimus/mycophenalate mofetil versus tacrolimus/sirolimus. Transplantation 2002;73:169– 177. Pescovitz MD, Dunn DL, Sutherland DE. Use of the circular stapler in construction of the duodenoneocystostomy for drainage into the bladder in transplants involving the whole pancreas. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1989;169:169–171. Bartlett ST, Woodle ES, Hibler T, et al. Stapled duodenal-cystic anastomosis in pancreas transplantation. Transplantation 1988; 46:460–462. Douzdjian V, Gugliuzza KK, Fish JC. Hand-sewn versus stapled duodenocystostomy in bladder-drained pancreas transplants. Transplant Proc 1995;27:3053–3054. Douzdjian V, Gugliuzza KK, Fish JC. Urologic complications after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation: hand-sewn versus stapled duodenocystostomy. Clin Transplant 1995;9: 396–400.